In Praise of Non-Anglocentric Frankensteins

The World Will Hunt You and Kill You For Who You Are

First off, let’s get this out there: I don’t like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. I get it, but I don’t like it. Del Toro talks [positively] about the book’s “fidgetey energy”, like a teenager questioning “why” to so many things, from capitalism to the meaning of life, and I think that’s also what doesn’t work for me, in the same way I can’t get on with the frenetic energy of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (which is basically ADHD: The Novel).

That said, I have two versions of it that I really, genuinely enjoy, and this post will contain spoilers for both: one is Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025), and the other is Çağan Irmak’s Yaratılan/Creature (2023).

This will be a long post. I apologise for nothing.

They are both completely different, and focus on very different aspects of the novel and the themes within it. Neither is completely faithful, but both do really interesting things with the source material.

“I am more attracted to making movies about people that are full of villainy, because ultimately it’s a more real way of seeing the world.” – Guillermo Del Toro (quote from the documentary Frankenstein: The Anatomy Lesson 2025)

I really love both adaptations for the very different things they say and are in conversation with. While Del Toro is making a film focused (among other things) on the nature of villainy and monstrosity, Irmak is making a mini-series about (among other things) the redemptive nature of community and its power to engender and shape Selfhood, and the corrupting effects of isolation upon the soul, body, mind, and spirit.

I love both those things, and I find them both really compelling ways to tell the same story.

[One is also telling it within the confines of 2.5 hours, and the other is an 8-part mini-series, so they also have completely different formats and storytelling frames.]

Check out the trailers to get a feel of them side by side!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9WZllcEgWrM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKl1QlR7P4U

Let me share some things I really love, comparing and contrasting the two versions.

CONTENTS

Naming (and Not Naming) the Characters

Framed Narrative Device

Victor/Ziya Comparison

Victor/The Creature vs Ziya/Ihsan

The Women

The Lab Setting

Religious Themes

Isolation & Redemption

What’s In A Name

Del Toro’s Victor & the Creature and Irmak’s Ziya & Ihsan are very different characters. Del Toro wanted to focus on the dialogue between fathers and sons, the isolation of those broken relationships and perpetuating abusive cycles. This is a story of rejection of a child, someone created from death then forced into monstrosity and to discover himself against this perception, because of the maker’s arrogance and hubris. Irmak wanted to tell a story of pushing the boundaries of science for the benefit of his family and community, the pain of losing members of that family and community, and the resurrecting of a parental figure (also rejected in horror) rather than the creation of an unwanted son. The themes are the same, but as it set in Ottoman Turkey, it has a distinctly Islamic cultural flavour, and is more grounded in communal relationships.

Even the names are meaningful: Victor, of course, has the meaning of the noun; the one who is victorious. In the end, he is defeated by his own arrogance and hubris, and broken down by the very victory over death he strived for. A victor is a singular person, often; many can run a race, but only one can win. Victor is a lonely, singular character – out in front of the scientific community, too far ahead to be fully appreciated or endorsed, and also too far gone to hear the words of warning and caution from behind him. Yes, he can achieve what he wants – he can triumph – but at what cost to himself, and others drawn into his orbit?

Del Toro plays with these themes with his Latin interpretation of Victor, whose passion cannot be stifled by cries of obscenity and blasphemy, and who does not understand why people, including his own brother, are frightened of him. Del Toro, I think, plays with the singularity of the victor as an image innate within the name of his protagonist, and the singularity of the monstrum, something strange and singular that gives warning or instruction of evil and the unnatural.

He embraces the original vision of Shelley in having Victor as the real monster, and this is the path he forges for his audience through Victor’s arc, and the explicit acknowledgement of his monstrosity in the dialogue with other characters like William and Elizabeth. Victor is ‘full of villainy’, and Del Toro enjoys playing with this on screen, and leading up to Victor’s suffering and death as his only means of redemption.

Having the Creature constantly repeat Victor’s name is not only to emphasise the bond of father/son between them, but serves as a statement of fact: Victor is indeed the victor, he has won, he has conquered death, and now there are no more horizons for him to chase. The Creature repeats his name as a statement of fact, of not just who Victor is, but what he is, and Victor’s horror and irritability stems not just from the fact that this is all his creation can say, but serves as a constant reminder that, now he has won, he doesn’t like it.

The Creature does not name himself Adam in this adaptation, nor does he receive a name from anyone else; the only word he can initially say is “Victor”, his creator’s name, which he repeats in various emotional states, until Elizabeth teaches him to say “Elizabeth”, also. The soft way the Creature pronounces this name drives Victor into a jealous frenzy and increases his disgust. Yet the Creature at no point confesses or professes romantic love for her – in these early scenes, he repeats the names as a child might say ‘father’ and ‘mother’.

As Del Toro emphasises the Creature’s composite makeup throughout the film, and the question is asked, in which part lies the soul, the question of in which part lies the name is absent. The Creature is a being without a name, on purpose, because he has surpassed the singularity of his creator. It is also a way of showing the audience that names are not necessary – for Victor to name his creation would be an act of conquest, of colonisation, of ownership, but Victor does not do this because he does not want the responsibility that goes with it. He does not want to be associated with the ‘monster’ he has made, because it doesn’t live up to his expectations, his ideals, and he has to reckon with the fact that he is its maker regardless.

To name something also means giving it and others a means to understand itself, and Victor withholds this, perhaps as another form of control. Yet in this, the Creature demonstrates that profound and mutual human connection is possible without names; he never learns the name of the old blind man, and yet his speech takes on the old man’s accent and patterns. They share a connection that does not require names or labels; it simply is, and it is understood through action and mutual respect and understanding. Similarly, the audience is invited into empathetic communion with the Creature through the perspective shift, just as in Shelley’s novel, and they can connect with him through his story, without a need for a name. This absence does not even feel like an absence; it simply is, and ultimately, no name or label needs to be placed on the Creature by others or by himself in order to come to an understanding of his own nature, and his self acceptance. He is known, and that is enough.

In Irmak’s adaptation, names are also important.

Ziya is a unisex Turkish name that means ‘light’, which reflects the character’s desire for enlightenment, fulfils part of a prophecy about the resurrection ritual required to get the machine to work, and also creates a sense of contrast to his inner darkness and character development journey. This signals that the story is not about a victor, a winner, but about a man whose passionate pursuit of knowledge and scientific boundary pushing for the sake of his community as much as for himself, leads him to some dark places.

Ziya begins by confronting three major medical horrors: first, finding out his mother’s friend, whom he has known from childhood, has leprosy. His immediate instinct is to touch her, and he is frustrated by the stigma and ostracisation she is experiencing, and the lack of effective treatment for her condition. Secondly, the pain that Ayise feels at the death of her mother in a contagion, and the fact that he cannot bring her mother back, has a profound effect on him. Thirdly, the horror of a cholera epidemic which takes his mother, and during which he personally works with his father, Dr Muzaffer (with whom he has a loving, if occasionally fiery, relationship) to provide limited medical assistance to the town.

Ziya goes to train in Istanbul, only to find that the academy has narrow views, and does not want students to go beyond the limits of currently understood medicine, which Ziya argues is anti-Islamic. He is thrown out for challenging his tutor, but Ihsan blackmails the principle into letting Ziya resume his studies. It turns out that the professor’s reluctance to allow students to investigate anything stems from his own insecurities at having a forged diploma, rather from any actual religious conservatism, which he hides behind. Ziya sheds light on the academy, but also on Ihsan, whom he first encounters at night. Ihsan is presented at first as the shadow-side of Ziya, but as the series progresses, it is clear it is also the other way around. Ziya tricks Ihsan into working alongside him, and even drugs Ihsan to get to the bottom of his secret machine. When it all goes wrong, it is Ihsan who pays the price, and Ziya resurrects him out of guilt and desperation, but then tries to hide what he has done by burning down the lab. He doesn’t try to burn Ihsan with it, but instead dresses him up as a leprosy sufferer and abandons him on the roadside. But hidden things keep coming to light, whether Ziya wants them to or not, and the consequences of his actions pursue him relentlessly, no matter how he tries to escape them.

Ihsan has a whole wealth of meaning, from simply ‘kindness’, to the deeply Islamic principle of showing your faith in actions, beautifying, or to do beautiful things. Ihsan helps people on the margins of society, and has a conscience about using dead bodies in his experiments – he covers himself from shame, but Ziya is more brazen and less concerned with morality. Ihsan extends to using a dead boar (pigs are haram), and drinks alcohol to excess, but he has lines which Ziya encourages him to cross. The result is his own horrible death, and resurrection, whereafter he is constantly referred to as a ghoul. Even so, he shows kindness and compassion to people he comes across, and seeks to protect other powerless people whom society has rejected, like him. In this way, he still lives up to his name, and ironically more so after his unnatural rebirth than when he was alive.

Ihsan and Ziya’s perversion of the natural order and use of forbidden texts pervert their very names and natures, but the narrative allows for them to return to those meanings, and explore (especially for Ihsan), how one can still enact kind and beautifying deeds as part of his social responsibility, even when he has been rejected by society and does not know how he fits into it anymore.

After a while, he re-names himself Ihsan, once his memory patchily returns, but he no longer knows who Ihsan was, or what that name means to anyone who might have known him. He has to find a new way to be Ihsan, and find a way back into himself, as well as a new way to understand his current existence. This forms Ihsan’s character arc, one rooted in Turkish drama as much as it is in Shelley’s novel. The result is that every episode is a banger, but Irmak manages to avoid a lot of the usual Diziler cliches, while making Frankenstein fit into a Turkish mould to be enjoyed by audiences used to certain formulae and conventions.

BACK

The Framed Narrative: Preface

Del Toro’s story begins in the Arctic, reset to 1857, but focused on a Danish expedition to the North Pole. There wasn’t really a Danish expedition at this time, there was a British one which aimed to find Franklin’s lost expedition, and the opening of Del Toro’s movie definitely gave me The Terror vibes. The framed narrative goes from here, and I really liked the opening being in Danish, rather than English, as that located it for me as a much less Anglocentric Frankenstein and set the tone.

Irmak’s story is prefaced with Captain Ömer’s narration, and he asks why are people so afraid of ghouls? It is because they are afraid the ghoul will start talking, and they will learn there is nothing after death. It is set on the snowy mountains in northwestern Turkey, and the city of Bursa which lies in the foothills. In the mountains is rumoured to be the treasure of a long-dead Byzantine prince, and so the mountains are frequented by treasure hunters who often lose limbs to frostbite. One such party, led by Captain Ömer, discovers an unconscious man in the snow, who seems to have been carried there by a mysterious figure. Thus sets off the framed narrative, initially shot as backstory.

Both these framed narratives have the same function as the book – the tale is told to men obsessed with their own horizons, their own chasing after legends and making something of themselves, and the tales serve as a warning against their overreaching, dangerous ambitions. Except, of course, Victor’s tale is told only to the Captain of the ship, but Ziya’s tale is told at first just to Captain Ömer, but then to the whole group, and is a warning not to one man, but a warning that benefits all the hearers of the same story. Even in this, we have the contrast of the singular and individual versus the community and society.

BACK

Victor & Ziya

Victor saws into a limb – Frankenstein (2025)Victor is scarred by his mother’s death as a young boy. She dies giving birth to William, his little brother, whose appearance favours their father, and makes him the favourite child. I can see the Latin American racial layers coming into play here, superimposed on the European aristocracy, and I really liked that dimension. I really enjoy the passionate Victor, much more than the cold, aloof, Germanic version who whines and complains a lot.

Ziya, on the other hand, is a grown man training under his father to be a doctor. He was deeply moved as a child by Asiye’s pain after she loses her mother, but his own loss comes when a cholera outbreak takes not only a large number of people in the village, but his own mother, too. Ziya is arrogant and hot-headed, but he has a close and loving (if tempestuous) relationship with his father. It is not the desire to supercede him that drives Ziya, but the determination to overcome death.

BACK

Victor & the Creature / Ziya & Ihsan

Victor’s relationship with the Creature is that of a bad father, procreating without woman, and not understanding either his creation, or how to have a relationship with him once he is made. This is the source of Victor’s horror and disgust – he has made something he doesn’t understand and cannot control, cannot unplug, cannot contain. Victor drinks milk, not alcohol, arrested at the point of his childhood and claiming an innocence he no longer has. He is searching for the secret to life to break the last barrier of science, for his own hubristic ideals, but he has no plans beyond this initial goal, which becomes all-consuming. When he does finally succeed, he immediately chains his creation to continue his control over it. He is encouraged in this endeavour by Harlander, a man riddled with syphilis, wanting to preserve his own mind in the new body of a new man.

Harlander reminded me strongly of both Basil and Henry in The Picture of Dorian Grey, and Del Toro himself described him as both antagonist and sympathetic. Yet he is not a corrupting influence – Victor is doing that all by himself. He also exceeds his own father’s cruelties, and the whole film is very much grounded in that central premise of broken father/son relationships.

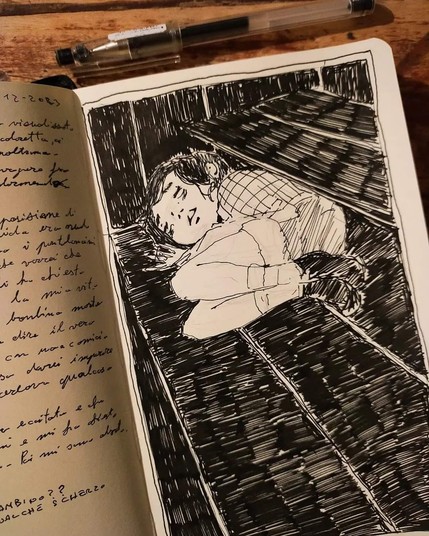

Ihsan hooking up a body to the machine – already looking like a cross between the Igor characters of some versions, and the Creature himself.Ziya’s relationship with Ihsan is very different – from the first moment they meet in Istanbul, there is a sense of both attraction and repulsion. Ziya is afraid of Ihsan’s strange behaviour at the University, and then Ihsan begins leaving him notes to let him know that he saw him spying. He behaves the way Shelley’s Creature does to Victor at the end of the novel, mirroring this relationship, and foreshadowing what is to come.

The horror here comes from resurrecting Ihsan as a deformed, blank slate – no longer Ihsan as Victor knew him in life, but something else, a ghoul, that cannot communicate in the same ways. When the newly resurrected Ihsan says “baba?” at the marketplace, it reinforces the horror at that relationship being reversed, and now being unfamiliar and fundamentally broken. That is not something that the embittered, lonely cynic with a secret heart of gold would ever say.

Ihsan and Ziya are reflections of each other, mirrored images, dark and light, death and life.Ihsan in life is already Othered – a disgraced ex-faculty member of the medical school, a drunk with aural hallucinations, acting erratically. Ihsan is both Creature and Harlander, the instigator of Ziya’s resurrection discoveries, and the resurrected who pays the price for his own ambitions as much as for Ziya’s.

In fact, Ihsan is in the parental or mentoring role, specifically asked by Ziya’s father to keep an eye on him. They are, from the outset, mirrors of one another, presented explicitly throughout as two parts of one whole, two sides of the same coin, life and death, Self and Other, monster and man. This is not a story about bad fathers and damaged sons, it’s a story about all the facets of a person, and how community is essential in shaping them and guiding them back to a sense of themselves.

Ihsan is already a recluse conducting haram experiments, despite having a kind and caring heart, and persuading himself he is doing questionable things for the right reasons. The lady with leprosy, living in a colony of fellow sufferers, kills herself after learning of Ziya’s mother’s death from Ayise, and reportedly falling into a depression (off-screen). Ayise learns about the degrading and detrimental impact that being cut off from mainstream society with a stigmatised disease can have, while Ihsan’s ostracism has left him lonely, bitter, and falling into heresy. Ziya doesn’t see this – he leans into it, and cuts himself off from the world with Ihsan in order to pursue their dangerous goals.

BACK

The Women

Then there is Elizabeth and Asiye. Again, two very different characters, playing very different roles within the same story. Also bear in mind that Del Toro’s story is a deeply Gothic piece, while Irmak’s pays homage to the European Gothic elements of the story, but is more rooted in Turkish drama traditions.

I loved Mia Goth’s portrayals of both Elizabeth and Clara Frankenstein, I loved the costuming and the colours, the relationships she had with William, Victor, and the Creature. I also appreciated that she wasn’t murdered by the Creature, as she is in the novel, to hurt Victor. Elizabeth Lavenza is the adopted sister and wife of Victor in the novel, following the pseudo-incestuous Gothic trope, but she’s also a mother-figure for him, and that is brought out in Del Toro’s version as sister-in-law with spurned romantic tension, and the fact Mia Goth literally plays Victor’s mother, so the fact that both he and William are subconsciously drawn to Elizabeth adds another pseudo-incestuous dimension by visual associations. I really enjoyed all those layers.

Elizabeth and Victor bonding over the beauty in death – Frankenstein (2025)I love that Elizabeth turns Victor down to marry his brother in this version, and that Ayise’s rejection of Ziya prompts the start of his redemption, where he pledges to do better, and give up his obsessions, arrogance, and pretensions, and live a simpler life. At this moment, a plate smashes, an omen that a crisis has been averted. Victor has no such redemptive moment – he ends up shooting Elizabeth and blaming the Creature. His crisis is not averted, but his moment of forgiveness comes on his deathbed. Unlike Ziya, Del Toro’s Victor is not afforded a chance to redeem himself, but only given the opportunity to suffer on the ice as hunter becomes hunted, and creation masters the creator. Elizabeth is not his redemption or his conscience, she’s a character given her own personality and space on screen, and she’s really well played.

It is very deliberate that the only women in this adaptation are Victor’s mother and love interest, and they are played by the same actress. This really reinforces a lot of the character notes and themes of the film, and again, I loved Mia Goth in this so much.

The women in Irmak’s adaptation are many and varied. There is Ziya’s mother and his grandmother, both of whom are great characters, and the neighbour with leprosy, who plays a part in both Ziya’s arc and in Ayise’s. There are the women in the circus where Ihsan finds a temporary family and home. There is Esma and the old lady in the village where Ihsan flees after the circus, and there is Ayise herself, the main female character and Ziya’s bride-to-be.

I could talk about all of them in detail, but I’ll focus on two of them, to match the two female characters in Del Toro’s version. Rather than it being Ayise and Ziya’s mother Gülfem, I will talk about Ayise and Esma.

Ayise and Ziya after the death of Ziya’s motherAyise is raised with Ziya after her mother dies, and Ayise’s father declares that there is nothing for her in the village, where many others have also died. She and Ziya fall in love, and Ziya’s mother gives them her blessing on her deathbed. I don’t personally believe Del Toro’s Frankenstein should pass the Bechdel test, which is something I’ve seen Internet Discourse about (because it doesn’t), but this adaptation does – Ayise shows herself to be a good-hearted, independent, and community-spirited woman, who continues to comfort and visit a family friend with leprosy, just as Ziya’s mother did. Ayise is the peace-keeper in the home not by capitulating or being quiet, but by shouting at Ziya when he’s wrong and making him apologise to his father when that is warranted. She is not his mother, but his partner, with a life of her own while he is in Istanbul, and I really loved that for her. She has her own lessons to learn about love and suffering, her privilege, and her place in the community and the world, apart from Ziya.

Esma is Ihan’s love interest – it takes him until he resurrects to have one of those, so arguably he only really comes to know a family and experience love after his short sojurn in Hell. Esma is the equivalent of the young girl (Safie) who lives with her blind grandfather in the book, who isn’t given space in Del Toro’s version. In this one, Esma is pregnant – her fiancé raped her, then refused to accept the child was his, and she ran away. She is in hiding with an old lady who took her in, and now Ihsan is offered the life of a father with a wife and child, but this is snatched from him when the baby is born, and Esma is murdered in an honour killing. The baby is given up for adoption, and Ihsan is once more without a family, but he wants Ziya to resurrect Esma for him so she can be his companion and bride. He decides against this at the end, to not condemn her to the life he is living.

BACK

The Lab

In Del Toro’s Frankenstein, the lab itself is an absolutely amazing set piece, with so many visual homages and great details. The colours are in dialogue with the costumes, the lighting works with everything, and it’s genuinely an amazing feat of set design. It’s very much a phallic feat of engineering, the kind of thing a certain type of man builds to compensate for the size of his estate… The storm is the catalyst, but so is the death of Harlander. There is a crucified Creature waiting rebirth, and there is beauty in the monstrous make-up. There is also the implication that the first thing the Creature must do is get himself off his cross (albeit one laid on the floor), and this is the opposite of Christ’s resurrection; even his birth is a blasphemy, and this is Victor’s fault, not his own.

Corpse parts are everywhere. When the Creature is born, Frankenstein’s first instinct is to chain him up and leave him below the lab in the tower, frustrated with the slowness of his intellectual progress. He threatens and abuses the Creature for being afraid, and for only being able to say “Victor”, the way an infant’s first word might be “Dada”.

The lab explodes with amazing pyrotechnics, and we see how Victor escapes first, then the Creature in the Creature’s point of view section of the film.

In Irmak’s version, the lab is within Ihsan’s house, a hidden secret, and this makes everything more contained and dramatic. It is in the woods outside Istanbul; lonely, unassuming, just like Ihsan himself. However – it is Ziya himself who gives life to Ihsan, not just via the machine and galvinism, but because he fulfils the prophetic conditions of the Book of Resurrection and understands it is his own blood, from his palms (on which, his grandmother told him, are engraved the 99 names of Allah), and he is willing to bleed and sacrifice himself to regain Ihsan. He initially took blood from an ethnic minority community in exchange for money, the same ones he defended against racism from a guard, but it is his own blood that is required.

There is no beauty in the horribly burned corpse of Ihsan – and when he rises, he is a blank slate, and bears no resemblance to the man Ziya loved. Ziya begs the resurrected Ihsan to speak to him, to give him some sign that Ihsan is still there, that he remembers who he was before he died. Ziya’s horror and rejection of Ihsan comes from his belief that Ihsan has come back wrong and empty. Ihsan is no longer a Professor, but needs to be toilet-trained and washed like a baby. His fear of fire leads him to nearly strangle Ziya, who chains him to his divan, horrified and not knowing what to do. Ziya recruits his friend Yunus to help him burn the lab down and get Ihsan out, planning to abandon him like an unwanted dog.

In both cases, there is a deep sense of fear and horror and profound disappointment in their creation, but for very different reasons. Frankenstein is appalled that he has begotten someone who cannot match his measure of intelligence, but also lacks the patience to teach him properly. He is horrified at the monster he has made, seeing only the unnaturalness of him, the imperfections; yet he intervenes in the market when Ihsan follows him there, and prevents the people from attacking Ihsan and hurting him. Ziya cannot do more than this, however – he runs away and abandons Ihsan again, and Ihsan stands there, confused and bereft, saying, “Baba?” (“Dad?” in Turkish). This is not the relationship that they ever had, and it’s not something Ihsan would ever say. In fact, he had a bad relationship with his own father, who rejected him, and now he is going through this abandonment again in his afterlife. Ihsan is about to be rejected and ostracised all over again, just as he was in life, but without the tools to deal with it, or the understanding of himself to cope.

Ziya is devastated at the loss of Ihan, but also wants to cover his tracks. He is afraid that Ihsan had been returned from Hell, and this was the reason for his fear of fire, his total amnesia, and his regression. He doesn’t want to be responsible, and so he abandons Ihsan on the road disguised as a leprosy sufferer, selfishly demands forgiveness, then runs away and leaves him there.

BACK

Religious Themes

I really like the religious questions and intertextual elements of (book) Frankenstein, and how this is echoed in Del Toro’s version with questions of the soul, forgiveness, and the final moment of embracing the sun – the moment that appears at the end of Cronos and Pinocchio, a favourite image for Del Toro that encapsulates his ethos. It’s the antithesis of Shelley’s ending, where the Creature walks out into the darkness, and yet it provides that ending, and imagines beyond it, to the sunrise of a new moment, a new beginning, a new man. Not only new, but accepted and seen, wholly and completely, and loved for who he is. This is contrasted with the monstrosity of Victor, condemned for playing God, and in whom a God who rejects and abandons His creations is held up as monstrous. Victor is criticised as being obscene and blasphemous – all of which he turns on his creation, who says, “To you I am obscene – to me, I am simply myself” (paraphrased).

In the book, of course, the ending is not as explicitly hopeful and optimistic, but in the book, the Creature murdered Elizabeth and has become “an instrument of evil”. Walton discovers the Creature mourning Victor. The Creature walks off into darkness to die, trying to reclaim his sense of self in the process. I prefer the adaptations that end on a note of hope, or those which really dive into the tragedy of the human existence and the central relationship.

In Irmak’s version, Ziya uses the teachings of the Prophet (pbuh) and the Qu’ran to justify pushing the boundaries of science, and is spurred to find cures for everything from his experiences in Bursa. His community’s cholera epidemic, seeing Ayise’s pain at her mother’s death, and seeing his mother’s friend with leprosy, all spur him onwards, but the crucial thing is finding a picture book in his father’s study disguised as “Stories for Children”, but actually relating the tale of the “Book of Resurrection”, a forbidden and lost tome. Ziya memorises the book even though his father punishes him for having taken a key and getting it out of its locked hiding place, and here we get some Necronomicon vibes/references, with alchemy. Ihsan, meanwhile, has been desperately seeking this book to push forwards with his own experiments (decidedly not halal, as his machine uses wild boar). Yet Ihsan tries to persuade Ziya and himself he only wants to use the machine to revive diseased and damaged organs, and cure bad diseases, not to raise the dead. It is Ziya who whole-heartedly sets out with the resurrection goal from the start, and shows Ihsan that he is lying to himself. This sets the experiments up as haram, and mirrors book Victor using animal bones and parts from the abbatoir in order to make his Creature, as well as human parts.

Neither Del Toro nor Irmak use the pick ‘n’ mix approach with their Creature, but I think this is Irmak’s reference to it, as well as using this to really underline the obscenities of the experiments for the audience. This is contrasted with Ziya’s enthusiasm – he doesn’t condemn Ihsan, but instead acts as a living version of the forbidden book, as the pictures and captions now exist in his head. It is fitting, then, that Ihsan’s accidental and tragic death makes him the prime subject for the machine, and turns him from Professor to Creature. The questions here centre also on the soul, but from the perspective of folklore and Islamic teaching; what is Ihsan now he is resurrected? Is he a ghoul? Do ghouls have souls? Can they be redeemed like living humans?

The machine in Irmak’s version is described as a sentient thing – mocking Ziya, looking at him. Ziya tells Cpt. Ömer that it was then he felt Shaitan beside him; this is the first time this pursuit has explicitly been aligned with the demonic, and it is by Ziya himself, who has now grown enough to recognise this.

BACK

Isolation & Redemption

What I love about Del Toro’s version is that every character is part of a self-contained Gothic world, where their very clothes are in dialogue with each other, with the sets, and with the story – but they are still all seeking some kind of human connection, with varying results. The Creature learns some very bleak lessons – everyone he cares for is taken from him, both the old blind man and Elizabeth, and his ‘father’ abandons him and rejects him. He learns self-acceptance at a terrible cost. This version of the Creature has no animal comforter, but kills wolves and comes to understand his place in the food chain and the dispassionate nature of the natural order: “The world will hunt you and kill you for who you are.” Yet, at the end of the film, he comes to an optimistic moment of embracing the sunrise, and stepping into the light. This is an important moment, but he does so on his own – this is a film about self-acceptance and self-discovery, about breaking generational cycles, and stepping into one’s own future, unshackled by the past. I like this, but for me, these types of stories lack the added dimensions of community.

What I love about Irmak’s version is that every single character has at least one friend, even if they are not part of wider society. They all have a hook to bring them back into community, if they can bring themselves to use it. Ihsan is so close to being restored to his living community when his only friend Hamdi lets him rest at his restaurant, but doesn’t recognise him, and Ihsan cannot communicate at that time, nor can he fully recall who Hamdi is. Ihsan’s living choices led him to reject society, and the family and care that Hamdi represents, and now after his rebirth, he is not able to reclaim what he rejected. Yet he is nevertheless provided with other companions and people who encourage him to find his own truth, his own sense of self, even as that is measured once more in loss and suffering. Even so, while human (and animal) connection is not necessarily sought after, it is given freely. People can be bad, but they can also be good; they can be cruel, but they can also be loving and generous. People are always simply people. Ihsan relearns all these lessons, and relearns his own compassion in the process, but at the cost of deep suffering. Yet, there is always the hope and the desire for community, for connection, for love, and that is what resonates with me so deeply about this whole piece. I love how Ziya deteriorates in the process of his flight, until he and Ihsan remain reflections of each other. I love how they get back together after a great struggle, and are only whole when they are reconciled. Only then are they free to go their own ways.

I think what sums up both adaptations is the idea that if you stop searching, stop seeking, stop striving, for something better than you have, there is no hope left. And the message of both versions is to ultimately embrace that hope, whether that comes from self-acceptance and understanding, or if it comes from religious redemption, or if comes from a return to community and a hope for closer connections. And whatever that is, that really resonates with me, too.

BACK

I think I’m going to leave this comparison alone for now, as this is already far too long, but if you have made it to the end, thank you for sticking with me.

I have so much more I could say – but perhaps another time.

In the meantime, I would highly recommend the two adaptations.

Like This? Try These:

- #AmReading: Body Gothic by Xavier Aldana Reyes Date January 1, 2020

- Goth is [not] Dead: (Sub)Genre-Chat Date March 8, 2019

- From Romancing the Gothic Blog: 100 Women Writers in Horror, the Gothic and Supernatural Fiction from the 18th Century to 2021 Date March 14, 2021

#gothicBooks #gothicFiction #gothicFilm #gothicHorror #longread