#happybirthday #owenwilson #actor #mobius #loki #AntManandtheWasp #Quantumania #Stick #HauntedMansion #Paint #MarryMe #SecretHeadquarters #theroyaltenenbaums #bottleroad #weddingcrashers #starskyandhutch #Cars #CarsontheRoad #NightattheMuseum #LittleFockers #TheInternship #TheGrandBudapestHotel #NoEscape #zoolander #Wonder #TheFrenchDispatch

#Mobius

“I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong… when we know that we actually do live in uncertainty, then we ought to admit it; it is of great value to realize that we do not know the answers to different questions.”*…

The immense complexity of the climate makes it impossible to model accurately. Instead, David Stainforth argues, we must use uncertainty to our advantage…

Today’s complex climate models aren’t equivalent to reality. In fact, computer models of Earth are very different to reality – particularly on regional, national and local scales. They don’t represent many aspects of the physical processes that we know are important for climate change, which means we can’t rely on them to provide detailed local predictions. This is a concern because human-induced climate change is all about our understanding of the future. This understanding empowers us. It enables us to make informed decisions by telling us about the consequences of our actions. It helps us consider what the future will be like if we act strongly to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, if we act only half-heartedly, or if we take no action at all. Such information enables us to assess the level of investment that we believe is worthwhile as individuals, communities and nations. It enables us to balance action on climate change against other demands on our finances such as health, education, security and culture.

For many of us, these issues are approached through the lens of personal experience and personal cares: we want to know what changes to expect where we live, in the places we know, and in the regions where we have our roots. We want local climate predictions – predictions conditioned on the choices that our societies make.

So, where do we get them? Well, nowadays most of these predictions originate from complicated computer models of the climate system – so-called Earth System Models (ESMs). These models are ubiquitous in climate change science. And for good reason. The increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are driving the climate system into a never-before-seen state. That means the past cannot be a good guide to the future, and predictions based simply on historic observations can’t be reliable: the information isn’t in the observational data, so no amount of processing can extract it. Climate prediction is therefore about our understanding of the physical processes of climate, not about data-processing. And since there are so many physical processes involved – everything from the movement of heat and moisture around the atmosphere to the interaction of oceans with ice-sheets – this naturally leads to the use of computer models.

But there’s a problem: models aren’t equivalent to reality.

So, what can we do? One option is to make the models better. Make them more detailed and more complicated. That, though, raises an important question: when is a model sufficiently realistic to predict something as complex as climate change? When will the models be good enough? We don’t have an answer to this question. Indeed, scientists have hardly begun to study this problem, and some argue that these models might never be sufficiently accurate to make multi-decadal, local climate predictions.

Nevertheless, changing the way we use ESMs could provide a different and better way to generate the local climate information we seek. Doing so involves embracing uncertainty as a key part of our knowledge about climate change. It involves stepping back and accepting that what we want is not precise predictions but robust predictions, even if robustness involves accepting large uncertainties in what we can know about the future…

[Stainforth explains the current state of modeling, efforts to make them better, and the problems those efforts encounter…]

… focusing on high-resolution modelling is dangerous not only because we have no answer to the question of when a model is sufficiently realistic. Investing in this approach also means we don’t have the capacity to explore the uncertainties, which inevitably encourages overconfidence in the predictions that models make. This is a particular concern because Earth System Models are increasingly being used to guide decisions and investments across our societies. Overconfidence in model-based predictions therefore risks encouraging bad decisions: decisions that are optimised for the futures in our models rather than what we understand about the range of possible futures for reality.

By contrast, perturbed physics ensembles and storyline approaches focus on exploring and describing our uncertainties. Placing uncertainty front and centre is important. When we make an investment or a gamble, we don’t just base it on what we think is the most likely result. We consider the range of outcomes that we think are possible – ideally these are characterised by probabilities, although this isn’t always achievable. It’s the same with climate change. We should not only make plans based solely on our best estimate of what might happen. We should also consider the range of plausible outcomes we foresee. Our knowledge of uncertainty is also part of what we know about climate change. We should embrace this knowledge, expand it and use it.

If we understand the uncertainties well, we can bring our values to bear on the risks we are willing to take. Uncertainty therefore needs to be at the core of adaptation planning while also being the lens through which we judge the value of climate policy and the energy transition. In my view, climate researchers and modellers wanting to support society should focus on understanding, characterising and quantifying uncertainty, and avoid the trap of seeking climate models that make reliable predictions. They may well never exist…

A more practical approach to preparing for climate change: “The model of catastrophe,” from @aeon.co

* Richard Feynman

###

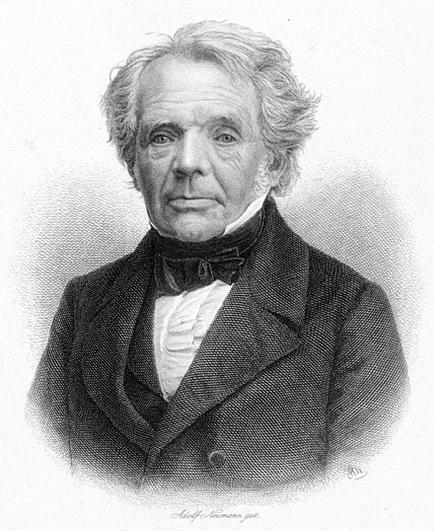

As we preference plausibility (over predictability), we might send never-ending birthday greetings to August Möbius; he was born on this date in 1790. An astronomer and mathematician, he studied under mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss while Gauss was the director of the Göttingen Observatory. From there, he went on to study with Carl Gauss’s instructor, Johann Pfaff, at the University of Halle, where he completed his doctoral thesis The occultation of fixed stars in 1815. In 1816, he became Extraordinary Professor in the “chair of astronomy and higher mechanics” at the University of Leipzig, where he remained for the rest of his career. Möbius made many contributions to both astronomy and the math that underlay it: he was among the first to conceive the possibility of geometry in more than three dimensions; he introduced homogeneous coordinates into projective geometry; and he pioneered the barycentric coordinate system… all parts of the intellectual foundation of the complex system modeling described above.

But while he was an influential scholar and professor, he is best remembered for his creation of the “Möbius strip.”

#astronomy #augustMobius #augustMobius2 #complexSystemModels #complexSystems #culture #history #mathematics #mobiusStrip #mobius #mobiusStrip2 #models #planning #plausibility #predicition #science #technology #uncertainty

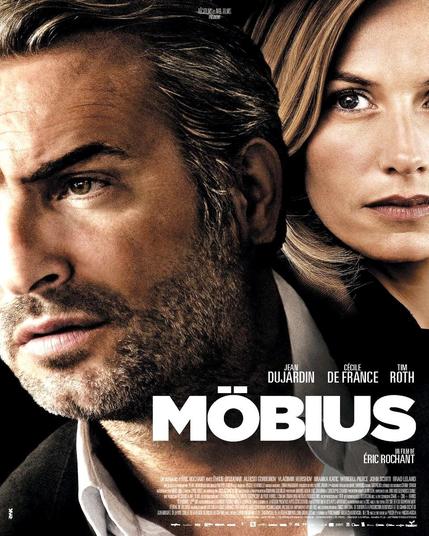

𝐋a 𝐒éance du 𝐒oir

𝐌𝐨̈𝐛𝐢𝐮𝐬

Film écrit et réalisé par Éric Rochant en 2013

Avec Jean Dujardin , Cécile de France , Tim Roth et Émilie Dequenne

*Jean Dujardin et Cécile de France forment un couple glamour dans cette romance hitchcockienne.

#Möbius #ÉricRochant #JeanDujardin #CécileDeFrance #TimRoth #ÉmilieDequenne

#classic #cinegenres #culte #classic #cinema #film #movie #LaSéanceDuSoir

𝐋a 𝐒éance du 𝐒oir:

https://cinegenres.com/film-de-la-soiree/

“It might help to think of the universe as a rubber sheet, or perhaps not”*…

You have most likely encountered one-sided objects hundreds of times in your daily life – like the universal symbol for recycling, found printed on the backs of aluminum cans and plastic bottles.

This mathematical object is called a Mobius strip. It has fascinated environmentalists, artists, engineers, mathematicians and many others ever since its discovery in 1858 by August Möbius, a German mathematician who died 150 years ago, on Sept. 26, 1868.

Möbius discovered the one-sided strip in 1858 while serving as the chair of astronomy and higher mechanics at the University of Leipzig. (Another mathematician named Listing actually described it a few months earlier, but did not publish his work until 1861. Indeed, it had already appeared in Roman mosaics from the third century CE.)…

The discovery of the Möbius strip in the mid-19th century launched a brand new field of mathematics: topology: “The Mathematical Madness of Möbius Strips and Other One-Sided Objects.”

* Terry Pratchett, Hogfather

###

As we return from whence we came, we might wish a Joyeux Anniversaire to Denis Diderot, contributor to and the chief editor of the Encyclopédie (“All things must be examined, debated, investigated without exception and without regard for anyone’s feelings.”)– and thus towering figure in the Enlightenment; he was born on this date in 1713. Diderot was also a novelist (e.g., Jacques le fataliste et son maître [Jacques the Fatalist and his Master])… and no mean epigramist:

From fanaticism to barbarism is only one step.

We swallow greedily any lie that flatters us, but we sip only little by little at a truth we find bitter.

Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest.

A thing is not proved just because no one has ever questioned it.

#diderot #encyclopedie #encyclopedia #history #literature #mathematics #mobiusStrip #mobius #topology

《不眠日》白敬亭|獨家專訪|不眠日第二季要看觀眾回饋

電視劇《不眠日》講述警官丁奇在時間回溯中對抗犯罪、守護正義的故事。

人物的命運展現人性的複雜,也探討人與時間的關係。

人民文娛、微博視界大會對話導演劉璋牧、編劇畢薔、總製片人Legolas_Zheng ,講述《不眠日》的匠心故事。

不眠日導演稱讚白敬亭有導演思維

轉自微博人民文娛2025.10.18

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭現場清唱不眠日插曲

在不眠日追劇團活動現場,白敬亭談及劇中插曲《Feifei Run》。

他說,這首歌他自己已經聽了很多年,

覺得和這部戲的氣質與調性高度契合,

所以主動聯繫了木馬樂隊洽談合作,又重新編曲錄製,才有了現在的呈現。

轉自微博人民文娛2025.09.19

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|查案查到鐵板!但我的任務就是抓到你

丁奇查案卻遭墨遠致反將一軍,故意挑釁,投訴丁Sir濫用職權。

被召回警局的丁奇因情緒激動又拿不出證據,被局長當場停職

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.24

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|集合!不眠日高燃爆破打戲來襲!

美好的下午,由燃爽丁Sir開啟

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.24

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|五限循環花絮-不眠日的吻戲觸發條件

火中吻戲幕後大揭秘!最開始是尋找角度的丁奇白敬亭和安嵐文詠珊 !

走戲的時候還被開關難倒啦

除了火場當然還有煙花也必不可少!超級浪漫的場景完成得也非常棒呢!

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.24

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|放棄循環,只想你們都能平安在我身邊

當一切塵埃落定回歸正軌,丁奇也選擇了解除循環能力,

或許循環的意義就是為了大家都擁有圓滿結局。

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.24

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|看完不眠日遲遲走不出來

記錄下這一刻,循環在此刻定格

轉自抖音不眠日2025.09.24

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|逆轉時間的公式有了答案,哪句話喚起了你的回憶?

轉自抖音不眠日2025.09.23

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|不眠人們這是我給你們報的網課

私人飛機、八塊腹肌、巨額獎金…

這個定製版丁sir白敬亭獻給我的好詭秘~

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.23

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》不眠日五限循環花絮-墨總綁架結算畫面的背後

墨總宋洋獵殺時刻!

劇內兇狠拿下“雙殺”,劇外試戲動作貼心,

防意外碰撞,最後韓宇飛宋家騰 唐心曹陽明珠 也是“舒服”躺進後車箱,

碰頭也專注演繹~

更多精彩內容鎖定不眠日

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.23

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|不眠日片頭細節詳解送上

還在使用“一鍵跳過片頭/片尾功能”嗎?

可別說沒有告訴你,片頭的彩蛋隱藏著滿滿的不眠真相線索哦

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.23

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|不眠日每一幀都值得細品

不眠日五限循環,記憶往復,丁Sir白敬亭的高光時刻值得反復回味!

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.23

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|不眠日五限循環花絮-丁奇安嵐互通心意名場面

“你不是我的愧疚,是我的軟肋”互通心意名場面,

導演上場指導眼神拉絲,沒想到如此曖昧的背後,

是丁奇安嵐一對視就繃不住的大笑

劇內互相保護劇外幽默相處,怎麼看都精彩!

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.23

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|再來循環一次丁sir的“要你老命”!

轉自抖音不眠日2025.09.22

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|白敬亭帶專業團隊抓烏賊

“抓烏賊!”

“抓哪隻?”

“麻油雞”

“抓到了!”

轉自抖音不眠日2025.09.22

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰

《不眠日》白敬亭|群像刻畫這一塊簡直是氛圍感拉滿

警局小分隊和烏賊嫌疑人,

簡直就是為群像文學愛好者量身定制的視覺盛宴!

轉自微博不眠日2025.09.22

#白敬亭 #baijingting

#白敬亭baijingting #baijingting白敬亭

#バイジンティン #백경정

#向全世界安利白敬亭

#不眠日 #丁奇 #白敬亭丁奇 #丁奇白敬亭

#愛奇藝 #愛奇藝不眠日 #Netfilx #NetfilxMobius #Mobius

#不眠日五限循環花絮 #劉璋牧

#文詠珊 #宋洋 #劉奕君 #陳保元

#ชุติมณฑน์จึงเจริญสุขยิ่ง #ChutimonChuengcharoensukying

#茱蒂蒙瓊查容蘇因

#張柏嘉 #韓立 #宋家騰