The global appeal of the doughnut

This week it’s the now annual Global Doughnut Days, hosted by Kate Raworth and her Doughnut Economics Action Lab. There are events happening around the world and online, exploring and investigating the ongoing work around doughnut economics. As my own contribution, I thought I’d check in on how the doughnut is being applied around the world.

As a refresher, Doughnut Economics is a way of conceptualising global challenges. It was developed in the NGO world and popularised in Kate Raworth’s 2017 book, which I reviewed here at the time. Raworth builds on the idea of planetary boundaries, noting that as well as a set of environmental limits that we shouldn’t exceed, there are also social limits that we shouldn’t fall below.

Countries can fail by overshoot – too much carbon or pollution. They can also fail by shortfall – not enough education, healthcare or political freedom. We can put social and environmental limits together to give us an upper boundary and a lower boundary. Humanity thrives in the safe space between these boundaries.

A doughnut isn’t the only way to picture these boundaries. It’s not even the most intuitive, which would probably be to call them a floor and a ceiling. But it is the most fun way to describe them, and that’s the gift of the idea. Not many people are interested in economics. Everyone likes doughnuts. You would struggle to rally a group of ordinary citizens to discuss the trade-offs between environmental and social targets in their local economy. But you might get them to come to a workshop on doughnut economics.

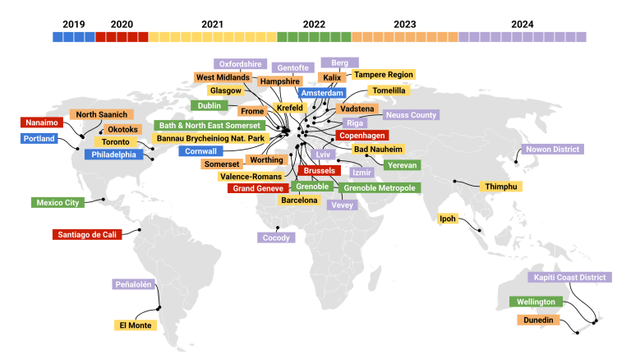

Lots of different places have now done exactly this, using the doughnut idea to explore the challenges of their particular city, region or country. Amsterdam were the first, and it has now spread far and wide:

The map above shows 50 different places that have used the doughnut in local government. The fact that this is local government and not community groups is a clear testament to the doughnut’s practical use, to my mind. This works. It works for decision makers and can lead policy making.

The map here is drawn from a recent study in the Journal of City Climate Policy and Economy. The researchers looked at these 50 places and what effect the doughnut had, looking at the sorts of policies the approach was generating. They found that the doughnut was useful for getting different departments working together, as they could see how their specific objectives contributed to a whole. It breaks local governments out of their silos and builds a shared understanding of what good lives look like in the city. Everyone’s work matters – the environmental team, the education department, those working on inclusion or urban planning or economic strategy.

It also prompted cities and regions to monitor different forms of progress. GDP won’t be enough, and the doughnut approach is ‘agnostic’ about growth – postgrowth rather than degrowth, if you like. Human thriving can only be measured across a range of different metrics, and so regions using the doughnut need to gather different sets of data.

Interestingly, the research found that doughnut economics programmes were proving useful enough to last. Of the 50 places surveyed, only two had dropped the idea with the end of the political term. Others had continued or been tweaked. Most are too early to tell just yet, but the doughnut seems to work for the political centre as well as the left.

As to whether it’s a truly global idea, that needs more time and my title may be jumping the gun. There’s only one example in Sub-Saharan Africa so far, and it’s atypical: Cocody is an up-market suburb of the city of Abidjan in Côte d-Ivoire, and wouldn’t represent the priorities of the wider city, let alone the country. There are five projects across the whole of Asia. Portland and Philadelphia were early adopters in 2019, but it’s noticeable that no US cities have followed their lead in the last five years.

On the other hand, this is the just the 50 locations in the study. DEAL are working with many more local governments that weren’t part of the study, and so the map doesn’t reflect the wider influence of the idea.

In short, the doughnut works. We can’t say just yet if it translates everywhere, but it certainly works in lots of different places. There are plenty of examples of its practical usefulness. If you want to apply it where you live, the action lab has all the tools you need to get started.

#planetaryBoundaries