Yakima watershed snowpack near record low for this time of year

There has been a lot of talk recently about the long-term drought in the Yakima River watershed, impacting irrigation districts in Eastern Washington and municipal water supply in the Seattle-area. Drought conditions continue in the region, though some improvement is possible later in the season.

Streamflows are certainly up in the watershed and reservoirs along the Upper Yakima River have begun to fill for the season but it is baffling to me that some professionals want to use this to spike the football. Of course streamflow is up, November is the wettest month of the year in the Pacific Northwest!

Yakima River watershed snowpack compared to average for WY2026. (USDA)Ingalls Weather thanks the support it gets from donors. Please consider making a small donation at this link to help me pay for the website and access to premium weather data.

Snowpack in the Yakima River watershed is telling a much different story. It sits at near record lows for this time of year as very little of the precipitation so far this season has come in the form of rain. This is the case even at mountain stations in the Cascades. Also note that reservoir storage remains well below average even though streamflow is up.

Snow is perhaps the most important “reservoir” the Inland Northwest has. The Columbia Basin in particular is especially dry and hot through the summer with the core of the region able to be considered a true desert by several metrics. At the same time it is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States.

This is thanks to snow in surrounding mountain ranges that helps to keep large rivers flowing through the course of the year. Early explorers of the Columbia Basin described areas around Othello and Moses Lake as a wasteland but dams and irrigation projects beginning in the New Deal-era completely changed the region’s economy.

Healthy snowpack keeps the rivers running through the very dry summers because in many areas mid- and high-elevation snow lasts into the early Summer months. Slow melt outs provide reliable water for growing year after year.

Reservoir storage at Keechelus Lake as of November 23. The blue line is this year, the green line is last year, and the red line is the average. (USBR)It is true that Yakima Valley agriculture continues to thrive thanks to numerous reasons, but this is in spite of water supply issues and not because water supply issues are non-existent. The very slow start to snowpack growth comes after three consecutive years of early snow melt in the Yakima River watershed.

Multiple years of drought add additional stress to both ecology and irrigation networks. In addition to increasing difficulty in managing water resources so that all users have enough to meet their needs, consecutive early melt outs also change how water flows through the groundwater system.

Now this is all a lot, but the reality is we won’t know what the situation looks like until April and May. One or two big winter storms aimed at Central Washington can rapidly change the situation. On the same theme, those winter storms (if they occur) are also less impactful than the late-Spring and early-Summer.

The speed of the melt out is the most important indicator of water supply. If it is too fast, resource managers have to dump precious water from the reservoirs to make sure they do not get overfilled and cause flooding issues. Even when a melt is slow, if it happens too early in the season it can lead to weak water supply in August and September.

Having more snow to begin with followed by a slow melt out is the obvious ideal for water availability in all Northwest watersheds. There are indications that this year will have improved mountain snow than previous years, but we are not seeing that come to fruition yet and it’s not clear if that will remove the drought.

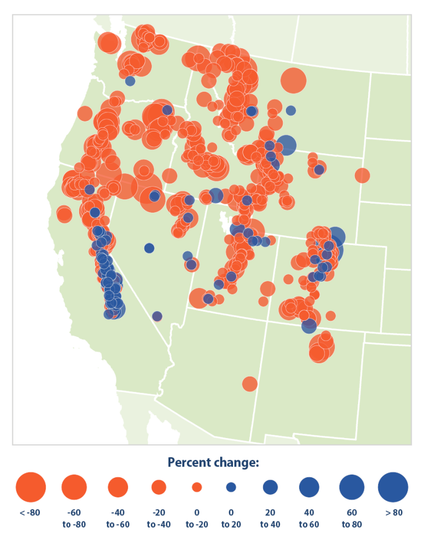

Change in April snowpack in the Western United States from 1955 to 2023. (EPA)Looking beyond 2026, long-term drought issues are likely to continue and worsen in the Yakima River watershed (as well as others in the Inland Northwest). Temperatures are warming over time.

Mountain precipitation is trending slowly up but more and more of this is falling as rain instead of snow in the winter. Late season snowpack is decreasing at more than 80% of long-term stations in the Western United States with the average decline in the region being about 18% from 1955 to 2023.

Meanwhile summer temperatures are trending warmer in Columbia Basin locations like the Tri-Cities. Warmer lowland temperatures lead to more watering demand as water evaporates faster during the growing season.

For a years water has been considered to be near limitless in the Columbia Basin and Yakima Valley. Declining snowpack over time will cause this resource to become less reliable with smaller waterways becoming scarcer faster than the Columbia and Snake Rivers. Irrigation districts and municipalities should be preparing now to be able to provide reliable water supply in future years.

The featured image is of a canal flowing through orchards in the Yakima Valley. (USDA)