The Gentleman’s Guide to Ham Radio: Unwritten Rules for Modern Operators

1,301 words, 7 minutes read time.

Amateur radio, or ham radio, is a unique hobby that combines technical skill, communication expertise, and community interaction. Success on the airwaves requires more than just a license—it demands understanding both regulations and the unwritten conventions that keep the hobby enjoyable and efficient for everyone. Operating responsibly ensures clear transmissions, prevents interference, and helps operators avoid being labeled a “lid,” a term for someone who makes avoidable mistakes on the air. This article explores the core practices that define effective ham radio operation.

Understanding Ham Radio Regulations

Every amateur radio operator is bound by regulations set forth by licensing authorities, and compliance is the first step in responsible operation. In the United States, for example, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) enforces rules that prohibit broadcasting music, transmitting encrypted messages, or conducting commercial activities over amateur frequencies. Operators must also perform station identification at the start of a transmission, every ten minutes during prolonged contacts, and at the end of a conversation. These regulations are not merely formalities; they protect the integrity of the amateur radio spectrum and ensure that operators can communicate openly without interference from unauthorized sources.

Knowing the law is only the foundation. Equally important is understanding how to transmit responsibly. Operators must choose the correct calling frequency for their band, whether on VHF, UHF, or HF. For instance, in VHF operation, 146.52 MHz serves as the standard calling frequency in the Americas. HF operators must also be aware of band segments, using the upper portion for voice modes and the lower portion for data. Ignoring these guidelines and transmitting randomly can disrupt ongoing contacts and frustrate other operators. Listening before transmitting is critical; it prevents unintentional interference and helps operators gauge whether a frequency is active or clear.

Proper Repeater Etiquette and Communication Practices

Once you understand the rules, the next step is learning effective communication techniques, especially when using repeaters. Repeaters are shared resources, and using them incorrectly can annoy fellow operators or even create safety hazards during emergency communications. One of the most common mistakes for new operators is “chunking” the repeater—pressing the push-to-talk button without speaking. This generates unnecessary noise on the frequency and signals inexperience. If such an accident occurs, it should be acknowledged promptly to avoid being labeled a lid.

Operators should also avoid using the term “broadcast” to describe amateur transmissions. Amateur radio is inherently a two-way communication system. It is designed for interaction and connection, not one-way transmission of information. Similarly, operators should become familiar with repeater personalities. Some repeaters are formal and structured, with strict conversation protocols, while others are informal or casual. Observing the repeater’s tone and conventions before transmitting allows new operators to integrate seamlessly, reducing the risk of conflicts or misunderstandings. Listening, patience, and proper identification are key components of this stage of operation.

Calling Frequencies, Codes, and Phonetics

Another critical aspect of ham radio best practices is understanding how to make effective contact on a frequency. Calling frequencies are designated portions of a band where operators can announce their presence, such as calling “CQ” to signal availability for a conversation. On VHF repeaters, it is unnecessary to use traditional CQ calls. Instead, a simple identification or request for contact is sufficient. On HF, the situation is different. Operators may use CQ calls to reach others across longer distances, but even then, care must be taken to ensure the frequency is clear. Listening for a few moments, announcing presence, and waiting for responses prevents interference and shows respect for fellow operators.

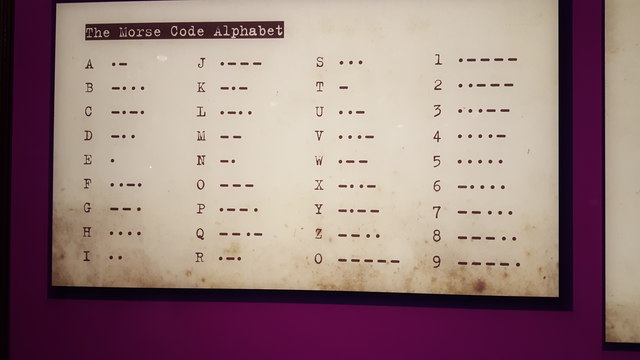

Operators should also understand the proper use of codes. Common codes, such as QSL for confirmation of receipt or QTH for location, are derived from Morse code practices and are widely accepted. Other codes like QRZ (who is calling) and QSY (change frequency) serve specific functions. In addition, the phonetic alphabet is essential for clear identification, particularly on HF or during contests, where signal clarity is critical. On VHF repeaters, however, phonetics may be unnecessary unless the call sign is difficult to discern. Using codes and phonetics appropriately ensures that communications are efficient and understandable, maintaining professionalism on the air.

Advanced Best Practices for HF and Data Modes

HF operations introduce additional technical considerations, such as antenna tuning and signal management. Operators should never tune an antenna over an active conversation, as the tuning noise can disrupt ongoing contacts. Instead, move a few kilohertz away from an active frequency before initiating tuning procedures. Similarly, when engaging in data modes using software like FL Digi, operators should be aware of RSID tones and mode identification to prevent confusion for others receiving the signal.

Calling CQ on HF requires attentiveness and timing. Operators should first confirm that a frequency is free, announce their presence, and then issue a CQ call in a measured manner. Ragchewing, or extended conversational contact, requires awareness of the other operator’s signal strength and readability. Signal reports, often expressed using the RST system—Readability, Signal Strength, and Tone—allow operators to determine whether a conversation is feasible. Providing or interpreting an accurate RST ensures that communication remains clear and efficient, and prevents frustration caused by attempting contacts under suboptimal conditions.

Effective Interaction During Nets and Group Communications

Net operations, where one operator serves as a controller for a structured group conversation, demand disciplined communication. Operators should not transmit until called upon and must follow the net control protocol. Interrupting ongoing conversations is acceptable only under certain circumstances, such as emergencies or brief interjections. Understanding how to enter and participate in group discussions without dominating the channel is an advanced skill that reinforces professionalism.

Equally important is leaving adequate pauses between transmissions. Allowing time for other operators to respond or interject ensures that conversations remain orderly and inclusive. Misusing the seven-three shorthand, or incorrectly referencing handheld transceivers, may mark an operator as inexperienced. Observing these subtle conventions distinguishes proficient operators from novices and reinforces the culture of respect that underpins amateur radio.

Conclusion: Mastering Ham Radio Conduct

Operating a ham radio effectively requires a balance of technical knowledge, regulatory compliance, and interpersonal skill. By understanding regulations, respecting calling frequencies and repeaters, and mastering proper communication techniques, operators can avoid common mistakes and participate fully in the amateur radio community. Listening attentively, using codes and phonetics appropriately, and maintaining awareness of other operators on the frequency ensures clarity, efficiency, and respect.

Ham radio is as much about community and shared experience as it is about technology. Following best practices allows operators to make meaningful contacts, expand their skills, and enjoy the hobby without causing interference or frustration. Mastery of these principles ensures that every transmission contributes positively to the amateur radio environment, fostering both technical competence and professional conduct.

Call to Action

If this story caught your attention, don’t just scroll past. Join the community—men sharing skills, stories, and experiences. Subscribe for more posts like this, drop a comment about your projects or lessons learned, or reach out and tell me what you’re building or experimenting with. Let’s grow together.

D. Bryan King

Sources

- Unwritten Rules of Ham Radio – KM6LYW Radio (YouTube)

- ARRL – Good Operating Practices

- ARRL Amateur Radio Operating Manual (PDF)

- NewHams.info – Guides for New Amateur Operators

- Rockford Amateur Radio Association – Repeater Conduct

- Ham Radio Etiquette (WRARC PDF)

- eHam – Basic Repeater Etiquette

- Operating Practices and Procedures (General Ham Radio PDF)

- Repeater Operating Practices – QCWA

- Ham Universe – HF Operating Tips

- Ham Radio Training School – Etiquette Guide

- HamRadioSchool – Etiquette & Operating Behavior

- OnAllBands – Amateur Radio Etiquette

- RSGB – Operating Practice & Procedure

- ITU Standard Phonetic Alphabet Reference

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author. The information provided is based on personal research, experience, and understanding of the subject matter at the time of writing. Readers should consult relevant experts or authorities for specific guidance related to their unique situations.

#amateurOperator #amateurRadio #amateurRadioAdvice #amateurRadioCommunity #amateurRadioEquipment #amateurRadioHobby #amateurRadioInstruction #amateurRadioKnowledge #amateurRadioNetwork #amateurRadioRules #amateurRadioSafety #amateurRadioSignals #amateurRadioStation #amateurRadioTraining #antennaTuning #callingFrequencies #communicationProtocol #contestOperation #cqCalls #cw #dataModes #digitalModes #effectiveRadioCommunication #emergencyCommunication #fccRegulations #flDigi #hamRadio #hamRadioBeginner #hamRadioBestPractices #hamRadioCommunity #hamRadioEtiquette #hamRadioGuide #hamRadioLicense #hamRadioOperations #hamRadioTips #handheldTransceiver #hfContacts #hfRadio #ht #morseCode #netControl #phoneticAlphabet #properCommunication #psk31 #pushToTalk #qCodes #qrz #qsl #qsy #qth #radioBestPractices #radioCallSigns #radioCheck #radioClarity #radioCodes #radioCommunicationSkills #radioContact #radioConversation #radioConversationEtiquette #radioEngagement #radioEtiquette #radioFrequency #radioGuidelines #radioHobbyist #radioInterference #radioLearning #radioLicense #radioListener #radioListening #radioMonitoring #radioOperation #radioOperationGuide #radioOperationTips #radioOperatorGuide #radioOperatorTips #radioSetup #radioSignal #radioTerminology #radioTransmission #ragchew #readability #repeaterCommunication #repeaterEtiquette #repeaters #rsidTone #rstReport #rtty #sevenThree #signalReport #signalStrength #toneReport #uhfCommunication #uhfContacts #vhfCommunication #vhfContacts