In the last thread, someone asked what exactly is it about consciousness that illusionists say is illusory?

One quick answer is that for illusionists, the properties people see in experience that incline us to think that consciousness is a metaphysically hard problem, are what’s illusory. In weak illusionism, the properties aren’t what they seem. In the strong version, which is usually what “illusionism” refers to, they don’t exist at all. But what exactly are these properties?

I’m a functionalist, someone who sees conscious experiences, and mental states overall, as more about what they do, the causal roles they play, than about any particular substance or constitution. It’s a view that I think provides a necessary explanatory layer between the mental and the physical, and so sees no barrier in principle to a full understanding of the relationship between them.

The usual argument against functionalism is that it doesn’t seem to account for qualia, the properties of phenomenal consciousness, the “what it’s like” nature of subjective experience, such as the redness of a red apple or the painfulness of toothache. Most functionalists, if they use the term, argue that qualia can be described functionally, such as pain being an automatic evaluation of a problem with a part of the body.

However philosophers have a number of thought experiments which claim to show that qualia and physics, including functionality, can be separated. This is where the illusionists come in. They argue qualia don’t exist, that the illusion is our impression that they do.

But that raises the question. What exactly are qualia? I gave the standard definition above, but it seems inadequate to settle this debate. The SEP article on qualia discusses four different versions, the simplest of which might be compatible with functionalism, but others that aren’t.

Daniel Dennett, in his 1988 Quining Qualia paper, a famous attack on the concept of qualia, provides the illusionist understanding, by noting four attributes commonly assigned to them. Summed up in the qualia Wikipedia article, they are:

- ineffable – they cannot be communicated, or apprehended by any means other than direct experience.

- intrinsic – they are non-relational properties, which do not change depending on the experience’s relation to other things.

- private – all interpersonal comparisons of qualia are systematically impossible.

- directly or immediately apprehensible by consciousness – to experience a quale is to know one experiences a quale, and to know all there is to know about that quale.

Dennett’s description of qualia is often decried as a strawman, something he constructs to easily knock down. However, we only have to look at the most popular qualia thought experiments to see these attributes confirmed. For example, consider Frank Jackson’s knowledge argument as described through the Mary’s Room thought experiment.

Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black-and-white room via a black-and-white television monitor. She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes or the sky and use terms like “red”, “blue”, and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal cords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence “The sky is blue.” What happens when Mary is released from her black-and-white room or is given a color television monitor? Does she learn anything new or not? Jackson claims that she does.

Within the assumptions of this scenario, why is Mary unable to acquire the information she can only learn by having the experience? She supposedly can’t read descriptions of it, because no one can provide that, matching Dennett’s ineffable attribute. She can’t conduct experiments to detect it, because it’s scientifically inaccessible, meeting the private attribute. And Jackson argues that qualia are epiphenomenal, which seems to meet Dennett’s intrinsic attribute.

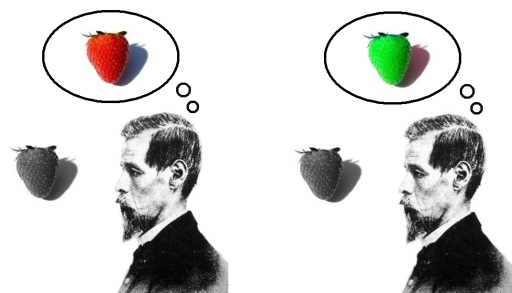

The same attributes are implied with the inverted spectrum concept, the idea that there’s no way to know if my experience of red looks like yours of green and vice versa. The fact that we seem unable to describe our experiences of color to each other, that they’re ineffable, private, and intrinsic, is what gives this scenario life. Likewise, the absent qualia / zombie argument, the idea of a being physically or behaviorally equivalent to a conscious one, but not itself conscious, only works if there’s no way to observe or deduce whether qualia are present.

And yet, in all these scenarios, the subject themselves still has first person access to these phenomenal properties. For that to be possible, for that access not to be prevented by the other attributes, it has to be special in some way, according to David Chalmers, in some non-causal manner, which gives us Dennett’s directly apprehensible property.

And what is it that makes Chalmers’ hard problem of consciousness metaphysically hard, if not these attributes? Remove them, and the thought experiments and metaphysical mysteries seem to disappear.

So the advocates of these thought experiments and illusionists seem to agree on what qualia are. They just disagree on whether they’re real. Functionalists and other physicalists, if they use terms like “qualia” or “phenomenal properties,” are referring to a concept with less theoretical commitments. Do Dennett’s attributes show up in the more reserved versions? As Dennett himself covers in the last section of his Quining Qualia paper, it becomes a matter of “in principle” vs “in practice”.

For ineffability, no one thinks describing experiences like the redness of red in a functional manner is obvious or easy, although it can be done to at least some extent, starting with the distinctiveness and high saliency of redness. For many experiences, the phrase, “a picture is worth a thousand words,” comes to mind. It might involve so much effort that it’s ineffable in practice, even if not in principle.

And there are limitations on our access to how these experiences are constructed. They are cognitively impenetrable, for the simple reason that it was never adaptive for our ancestors to be able to access the early processing, such as all the underlying associations and affects red stimuli trigger, but which figure in what red experience feels like. Which makes a full description of the experience impossible with only introspective information.

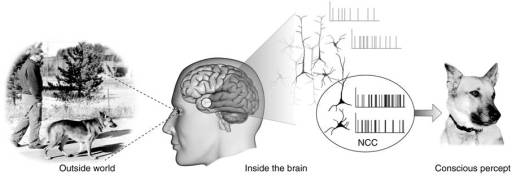

Mental content, until recently, was private due to technological limitations and our lack of knowledge about the brain. It still effectively is in virtually all cases. But with the progress in brain scanning technologies, we’re seeing the first cracks in this attribute. We still have a long way to go, but even though it’s early days, the idea that mental content is in a separate realm and utterly inaccessible seems less defensible with each passing year.

Without absolute ineffability or privacy, it’s not necessary to bring in direct apprehension. Which isn’t to say that we don’t have privileged internal access in practice, but it’s similar to the type of access the processors in the device you’re using right now have to read and write memory that aren’t easily observable from the outside.

And then there’s intrinsicality. Achieving functional descriptions of conscious experience typically requires looking at the upstream causes and downstream effects of what we think of as the experience. Intrinsicality assumes that there’s still something in between, something that remains with intrinsic properties, something distinct from the causal chain, somewhere where the prior causes culminate in the presentation, and from which the downstream effects flow, with some aspects still conceivably epiphenomenal. The functional shift here is to regard the experience as the whole causal chain, a more plausible stance in a massively parallel system with no central control point.

Clarifying these attributes as difficulties in practice, rather than absolute limitations in principle, both explains our impressions of them, and transforms conscious experience from an intractable metaphysical problem to a series of scientific ones.

This is one of the reasons I used to resist the illusionist label, and still prefer the functionalist one. The difference doesn’t seem that vast (a point David Lewis made in 1995), and mostly seems to amount to a lack of nuance in our initial understanding, rather than some deep unavoidable species-wide misperception.

And yet for a significant portion of the population, the strong intuition is that a functional description, while explaining behavior, still leaves out something important for experience. And here we run into an intuition clash. For someone convinced that an ineffable metaphysically private aspect remains, it doesn’t seem like something science can demonstrate is or isn’t there. It becomes an extra assumption some people hold and others don’t.

Which seems to leave us in the strange place where the two views are empirically identical, and the debate a purely philosophical one.

Unless of course I’m missing something. What do you think? Are functionalists overreaching for a non-gap explanation? Are there fact-of-the-matter differences between illusionism and functionalism I’m overlooking? And are there ways to demonstrate the reality or non-reality of ineffable private qualities?

Featured image credit

https://selfawarepatterns.com/2024/08/31/illusionism-and-functionalism/

#Consciousness #functionalism #illusionism #phenomenalConsciousness #Philosophy #PhilosophyOfMind #Qualia