Bernanos was totally wrong in regard to Christianity and the French Revolution. There had never been a “good” Revolution in 1789 which, Bernanos maintained, had turned “bad” only in 1793.

The destruction of Christianity was blatantly present from the very beginning, as is incontrovertibly proven by the simple fact that on October 29, 1789, no more than three and a half months after the fall of the Bastille, the taking of all religious vows was forbidden in France.

Sister Constance in the monastery at Compiègne, for example, could never make her profession as a Carmelite before going to the guillotine five years later. Further proof existed in the fact that just four days after this October 29 decree, on November 2, the totality of church property throughout all of France was confiscated and declared property of the state, completely stripping religious communities of their means of income.

Thus, from its very beginning, the total eradication of religious orders in France was a clearly stated purpose of the Revolution, as was also the humiliation of the once proud Church of France, brought to her knees before her sanguinary enemies by the decree of November 2, 1789. Her confiscated goods would finance the Revolution for ten years.

Professor William Bush

Author’s Foreword

What was this fatal decree?

Sr. Marie of the Incarnation, the sole surviving Carmelite of Compiègne and the first biographer of the martyrs, tells us that Blessed Constance entered the Carmel of Compiègne on May 29, 1788, and was clothed in the habit of Carmel on December 13 of that year. Canonically, she was set to profess her perpetual vows in December 1789. Professor Bush notes that Blessed Teresa of St. Augustine intended to allow Sr. Constance to make her vows on the anniversary date.

A Turning Point for France

On Tuesday, July 14, 1789, revolutionary insurgents stormed the Bastille, a royal fortress in Paris. Their successful siege and capture of the commander marked a decisive shift in Paris, turning popular sentiment toward the revolution and away from King Louis XVI’s weakening administration. Soon, the revolutionary spirit spread across France.

New Cause, New Laws

Meanwhile, in the Constituent Assembly—a governing body formed in June 1789—deputies, emboldened by these events, moved to create new laws aligned with the revolutionary cause. Today, thanks to the collaboration between the French National Library and Stanford University, we can read the daily acts of the Constituent Assembly and discover exactly how the fatal decree of October 28-29, 1789, came into being. Below, we present our translation of the daily proceedings (in italics) from the Assembly’s Wednesday session on October 28, along with a brief commentary for clarity.

Mr. Rousselet

On behalf of the reporting committee, Mr. Rousselet presents letters from two monks and a nun, requesting the Assembly to clarify its stance on the profession of vows. He suggests prohibiting perpetual monastic vows.

1746 – 1834

Michel-Louis Rousselet was a deputy from the bailiwick of Provins (Seine-et-Marne), located southeast of Paris. Although he served in the Assembly for only two years—from March 30, 1789, to September 30, 1791—those years proved pivotal for Catholics in France. His report, which called for the suspension of religious vows in monasteries, received the support of Guy-Jean-Baptiste Target, a deputy from the bailiwick of Paris-Outside-the-Walls.

Guy-Jean-Baptiste Target1733 – 1806

Here, we continue to translate the proceedings from that fateful day in the Assembly…

Mr. Target

Mr. Target requests a postponement on the core issue and proposes the following decree:

“Upon reading the report…the Assembly postpones the question of professing vows but provisionally decrees that the profession of vows will be suspended in monasteries of both men and women.”

Several clergy [who were deputies] argue that this provisional suspension effectively decides the question and invoke the regulation requiring three days of discussion for major issues.

The decree proposed by Mr. Target is adopted.

[Following this, the Assembly session addresses unrelated matters.]

French Revolution Digital ArchiveA collaboration between the Stanford University Libraries and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Tome 9 : Du 16 septembre au 11 novembre 1789, Séance du mercredi 28 octobre 1789, Séance du jeudi 29 octobre 1789, pages 597–598

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY

PRESIDED OVER BY MR. CAMUS

SESSION OF THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29, 1789

After the secretary reads the minutes,

Mr. de Bonnal

Takes the podium to make what he calls “a few protests” against the decree from the previous day. He asserts that the clergy should have raised objections, and requests that his own be recorded under the title of “observations.”

Mr. Target

Mr. Target notes that traditionally, the minutes do not include individual protests made against the Assembly’s decrees.

This brief dispute concludes with a ruling on the previous question.

The President

The President then calls for the day’s agenda.

Bush, W. 1999, To quell the terror: the mystery of the vocation of the sixteen Carmelites of Compiègne guillotined July 17, 1794, ICS Publications, Washington, D.C.

de l’Incarnation, M 1836, Histoire des religieuses carmelites de Compiègne conduites a l’échafaud le 17 juillet 1794: Ouvrage posthume de la soeur Marie de l’Incarnation, T. Malvin, Sens. Accessed 16 July 2021, babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c041438717&view=1up&seq=117

Translation from the French text is the blogger’s own work product and may not be reproduced without permission.

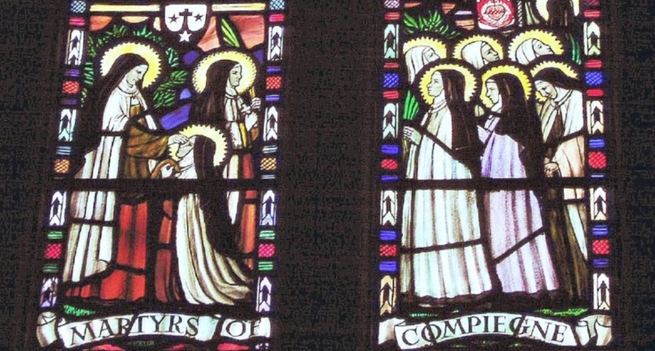

Featured image: This detail from a stained glass window depicting the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiègne was designed by stained glass artist Sister Margaret of the Mother of God, O.C.D. (Margaret Rope). It is one of her most famous windows in the chapel of the Carmel of Quidenham, England. Image credit: Discalced Carmelites

https://carmelitequotes.blog/2024/10/28/bush-29oct1789/

#BlessedConstance #constituentAssembly #FrenchRevolution #history #inspiration #MartyrsOfCompiègne #persecution #religiousProfession #vows