The thread about the Edinburgh Police Box; architectural Time Traveller but no TARDIS!

The year 2024 was celebrated as the 900th anniversary of the “foundation” of the city of Edinburgh and 2025 is also an important local commemoration; the centenary of the appointment of the wonderfully named Ebenezer James (“E.J.“) Macrae as City Architect. His twenty years of service was a time of great change in our built environment and his office was directly responsible for much of that, not without good cause has he been dubbed “the man who shaped modern Edinburgh“. His tenure is characterised by both the volume of public buildings and housing that was erected and also their distinctive style; at once both modern in form and function but also very sympathetic to tradition. A splendid example of that contrast is the Edinburgh Police Box; a mix of anachronistic classical styling and what was then the cutting edge of modern policing.

Former police box at corner of Waverley Bridge and Market Street. CC-by-NC-SA 2.0, Ian T. Edwards via Flickr.The first police boxes with telephones were established in Chicago back in 1881, just 5 years after the unveiling of the telephone itself by a son of Edinburgh. In 1923, Chief Constable Frederick Crawley of Newcastle City Police instituted what would become known as the Police Box System to Sunderland and in doing so revolutionised British policing. He was looking to increase the efficiency of his his force and focused on trying to reduce time spent by officers walking to and from their beats; he estimated up to a quarter of each man’s time on shift was wasted in this manner. His solution was decentralisation. By placing many small, telephone-equipped police boxes at strategic points throughout the city, officers had shorter distances to walk and could devote more time to duty. Crawley recognised this would place the police more centrally within the communities they were expected to serve, creating a ready point of contact for the public – thus increasing the efficiency of reporting emergencies and also making it far easier for the police to contact and coordinate their own officers. Boxes could also be used as temporary lock ups for prisoners while transport was summoned, avoiding the long and often dangerous walks with them back to a police station. A final and significant attraction was that the increased efficiency also allowed the closure of most district police stations and therefore afforded a significant cost saving.

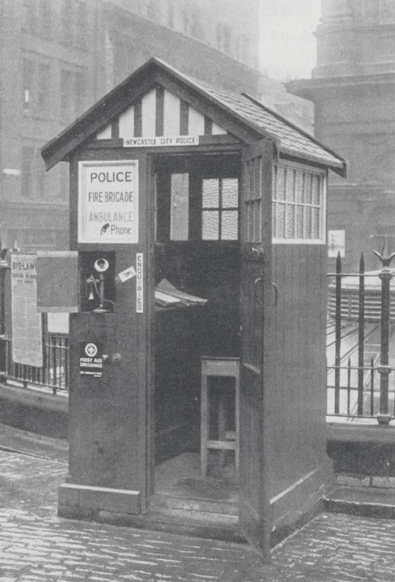

Wooden police box of the type instituted by Crawley for Newcastle City Police. Note the public-facing telephone and first aid boxes mounted to the left of the door. From The Police Journal, vol.1, No.1, January 1928Police boxes soon spread across the country but Edinburgh, as is often the case, was rather slow to catch on. It was not until May 1928 that a deputation was sent by Chief Constable Roderick Ross from the Edinburgh City Police to inspect the system in Newcastle. This was at the insistence of the Scottish Office who refused to sanction an increase in headcount for Ross and instead wanted efficiencies. He submitted a strongly favourable report to the Town Council, which approved a box system for the city in 1929. Ross served as Chief Constable for the exceptional term of 34 years and it was towards the end of his long watch that his force would be wholly and rapidly modernised.

Roderick Ross, when Chief Constable of Ramsgate Borough Police c. 1898The Edinburgh Evening News threw its editorial weight behind the scheme but also amplified significant local concerns that the appearance of boxes would have a detrimental effect on the city. As the system spread, there had been a plethora of different design styles before a utilitarian, standardised version was developed for the Metropolitan Police by the architect George Mackenzie Trench. Trench’s design is instantly familiar to generations of Dr. Who fans as the TARDIS. But “Cheapness has been obtained in England” wrote the News’ editor “by mass production, but Edinburgh has an architectural standard of its own, which the Cockburn Association endeavours to maintain.” The gauntlet was thus thrown down to the City Architect’s office that something altogether different and better was needed.

George Mackenzie Trench standard police box at the National Tramway Museum, Crich. Note the light on the roof, which would flash to indicate an officer was required to attend the box. CC-by-SA 3.0 Dan Sellers via WikimediaE.J. Macrae, along with his assistants Andrew Rollo and James A. Tweedie are credited with the design of the Edinburgh Box, with the signature of their colleague Robert Somerville Ellis on some of the drawings. The initial inspiration may have been taken from the barrel-topped box used in Sheffield which was used as an illustrative example by the Evening News. Two alternative designs were prepared and plans and models were put to the Lord Provost’s Committee in December 1929. The preferred option was then “submitted for the consideration of the Fine Art Commission“. After that a full-size wooden mock-up was erected on the corner of George Street and Frederick Street in October 1930 to test the practicalities of installing boxes and also to familiarise both the police and the public with the design.

Sheffield City Police box, as used as an illustrative example by the Evening News. September 13th 1938The approved box was, dare I say it, an iconic piece of British street furniture design, unique to the city and instantly at home in its environment. It is described in architectural terms thusly:

Rectangular cast-iron police box with classical details, 6ft by 4ft on plan, 2-bay pilastered long elevations, one of which contains door bearing City Arms. Painted blue. Single bay short elevations surmounted by open pediments containing ribboned wreath paterae. Saltire patterned glazing to all elevations. Low-pitched roof.

Official description of the Edinburgh Police Box from Historic Scotland listing

Each box was constructed of prefabricated cast iron panels produced by the Carron Company in Stirlingshire and tipped the scales at over two tons. The understated classical styling was decorated only with a small cast iron castle motif from the city’s coat of arms on the door and on each gable a wreath; symbolising power or triumph. Inside they were equipped with a desk, flip-down seat, telephone, sink and a small wall-mounted electric heater. There was shelving, pigeon holes and notice boards on the walls to accommodate items such as logbooks and forms and hooks were provided for hanging coats, helmets and capes. Hooks were provided for “beat keys”, premises officers on duty were expected to visit and check, or need access to, during their duties. An unofficial but entirely necessary function of the sink was an ersatz urinal; 8 hours in a district with few or no public toilets was a long time for a beat officer to spend without spending any pennies! (This was apparently best achieved by balancing on the stool and taking careful aim. Each box was provisioned with a supply of bleach to keep things as sanitary as possible.) All of this came at a price however; £58 per box (before foundations and services were laid), far more than the wooden hut type which had cost £13 each in Newcastle or £43 for a reinforced concrete standard box as used by the Metropolitan Police.

Sketch design of the Edinburgh City Police Box, redrawn by self from a copy of the original in the Edinburgh City Archives. The original is signed RSE (Robert Somerville Ellis), 6th September 1928. From Dean of Guild Court of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Police Boxes, Lord Provost, Magistrates and Council of the City of Edinburgh, 26th August 1932.On the outside of the box were small doors that gave members of the public access to a Speakerphone that would connect them to police headquarters and another containing a first aid kit. The Speakerphone was a hands-free system activated upon opening of its door. It was felt at the time that the general public were not familiar enough with the use of telephones to provide a handset, and it was also harder to accidentally damage or vandalise.

A police officer demonstrating the use of the Speakerphone unit. Opening the box door automatically connected the phone to the headquarters switchboard. Photo via Lothian & Borders Police WordPress.Despite the best efforts of Macrae’s office to produce a design that was sympathetic to Edinburgh’s built environment, not everyone was pleased. “W.M.H.” wrote to the Evening News that the box at the foot of Drummond Street by the old City Wall was a “case of outrageous vandalism and should be prohibited.” They questioned who in the authorities was responsible for such “outrages” and challenged the city’s heritage watchdog – the Cockburn Association – to “get busy!“. In Portobello, the Communist party had a particularly niche objection; it charged that the boxes were “designed for use in a rebellion” and that “the master class knew that they were driving the workers to desperation, and they were preparing in advance to deal with rebellion“.

The police box at Drummond Street, immediately in front of the Flodden Wall. The photo dates from 1951 and the box still sports its white stripes applied during WW2 to make it more visible during blackout conditions. Records of RCAHMS, SC1164082. © Crown Copyright: HESBoxes were installed throughout 1932 and a considerable public relations exercise was undertaken to get the public to understand how to use them. The Evening News maintained a regular stream of editorials on the subject, Chief Constable Ross gave numerous lectures, model boxes were taken around schools to show children how to use them and Boy Scouts were encouraged to learn the location of as many boxes as possible as part of their Pathfinding badge. In the final run-up to commissioning, public demonstrations of the boxes in use were staged and the press cameras invited.

Photograph showing a staged accident to demonstrate the use of the public call facility on the new police boxes, along with an operator of the switchboard at police headquarters on the High Street that received the calls. Scotsman, May 26th 1933.The box system and “a new era in the history of Edinburgh City Police” was inaugurated in its entirety on Sunday May 28th 1933 at 6AM. This was a year later than intended, a delay that the Lord Provost blamed on the General Post Office which had been slow to install the necessary telephony infrastructure (500 miles of underground and 23 miles of overhead wire).

Bailie Rutherford Fortune places the first call on from a police box with Chief Constable Ross (dark coat and light hat, with moustache) and Mr F. J. Milne (light coat and dark hat, with umbrella) Secretary of the Post Office in Edinburgh.The boxes were only one part of a greater overall system; policing of the city was entirely restructured at this time. The boxes were allocated to four divisions, each with its own headquarters – A at Braid Place, B at Gayfield Square, C at Torphicen Place and D at Leith – and were numbered sequentially and by division. A map of the all their locations as installed in 1933 can be seen here. Each division had a dedicated pool of motor vehicles for response and prisoner transport and was supported by a non-territorial traffic and mounted division (E) based in the Cowgate. At the same moment that the boxes were first unlocked for duty, the doors of nine district police stations (at the Pleasance, West Port, Abbeyhill, Piershill, Stockbridge, Waverley Market, Morningside, Gorgie and Newhaven) and eighteen smaller sub-stations closed for the last time. Most of these sites were disposed of, leaving only the four divisional stations, a sub-divisional station for Portobello plus city police HQ on the High Street.

The Leith Police. Relaxing on break time with tea and “pieces” at Leith Police station in 1930. Photograph by Photo Press Agency, CC-by-NC-SA via ThelmaThe reduction in manpower required by the box system saw fifteen open vacancies for constables written off, three inspectors and five sergeants made redundant and a further five sergeants demoted to constables. Overall the changes reduced the running cost of the force by £5,800 annually.

Six or seven constables might be based out of a single box and would serve their entire 8-hour shift from it, returning after every half hour or hour long “turn ” of their beat to check in with base by phone, write up their logbook and take breaks. Check in calls were performed according to a strict timetable and if any officer missed one his absence would be noted and a colleague sent to investigate. Men on duty could expect a visit by a section sergeant once every shift. The boxes were accessed by a universal key, which each officer kept on his chain with his whistle. A blue light on the roof of the box would flash to let him know that there was a call waiting for him. Sometimes these lights had to be mounted on an extension pole to be better seen from a distance and in the case of the box outside the Tron Kirk on the High Street, it was a high-mounted “sky lantern” on the building on the corner with North Bridge.

The High Street “sky lantern” is still in place on the corner with North Bridge, appropriately mounted next to a symbol of modern police surveillance, the CCTV camera.Commencing in 1938, air raid sirens began to be installed on top of the roofs of many of Edinburgh’s boxes as part of the city’s ARP (Air Raid Precautions) measures. By April 1939, thirty two sirens had been installed, all controlled from master switches at HQ on the High Street and tests of the system were under way, helping to familiarise the public with the sound. In May 1940, a writer to the Evening News’ letters page using the pseudonym Tenement Warden and Old Contemptible suggested that police boxes be used to store “machine guns, hand grenades, ammunition and rifles” to deal with enemy paratroopers and “Hitler’s Fifth Column and Fascists all over Britain“. I cannot see that this idea was ever taken seriously!

Photograph of the type of air raid siren installed on the roof of Edinburgh police boxes. Evening News, 30th November 1938In 1939, the annual Estimates of Expenditure of the Town Council reported that there were now 143 police boxes in the city backed up by 40 telephone pillars. Running costs were £3,350, not including £250 for maintenance, £800 for electricity and £3,350 to the Post Office for telephony. The authorised strength of the force was reported as 871, comprising 688 constables, 91 sergeants, 30 inspectors and one each “woman sergeant” and “woman constable“.

In practice the boxes proved to be stiflingly hot in the summer and bitterly cold in the winter; the issued heater was much to small and badly located, so boxes often sourced their own additional heaters to make them more habitable. On account of the metal structure they “sweated considerably” in damp weather as a result of condensation. The roof interior would eventually be insulated in 1956 to try and tackle this particular issue. All boxes were to have been provided with both electricity and a water supply but in the end economies meant only 86 of the 140 boxes were plumbed in. It was some time before enamel mugs, at 6d per unit, were issued from which the water could be drunk and it took until 1947 for the Town Council to approve an expenditure of £781 to equip each box with an electric kettle for making tea.

“For Bobby’s Cup of Tea”, Evening News, 5th June 1947Uncomfortable they may have been, but the boxes proved to be immensely strong. This was demonstrated in November 1945 when PC John Anderson – on what was his last day of service of a thirty years police career – escaped with a fractured leg when a fire engine crashed into his box at the foot of the Canongate. In 1954, PC Donald Budge walked away from his box at Balgreen with only cuts and bruises after a two ton lamp standard, being installed nearby fell onto the roof of the box he was sitting in. The damage to the box was restricted to a cracked roof, a broken window and cracked sink. Also that year, two constables in the box at Murrayfield Avenue survived it being struck by lightning, although the interior lights, radiator and telephones were put out of service and the air raid siren on the roof activated itself.

It took the public some time to get used to the new system. In 1936, three years after its institution, Chief Contable W. B. R. Morren lamented that there was a general ignorance, particularly on the part of grown ups, as to the location and facilities offered by boxes. Boxes were always subject to interference and vandalism throughout their working lives. The authorities were keen to make an example of anyone caught in such an act and the first prosecution came in November 1933 when 19 year old Colin Gosschalk was caught breaking into the first aid compartment of the box on Prestonfield Avenue. His defence that a friend had dared him to do it was not accepted and he was fined 10s (the maximum being £2).

The system was not without its critics as evidenced in the columns of and letters to the Evening News – a particular but unfounded complaint was that constables were either never in the boxes when needed, or spent too much time sheltering within them rather than “on the beat” – a classic of the Schrödinger’s box genre! In an interview with the ‘News in 1946, Chief Constable Morren said that boxes “fulfilled and continues to fulfil a very useful purpose, but… did not develop that contact between the police and the public which was so desirable, and it had been proved that the system had not been the success in that direction that was anticipated”. Brigadier-General Dudgeon, HM Inspector of Constabulary for Scotland said that the box system had “proved to be of value to both the police and the public” but “the beat constable is the eyes and ears of the police, and be careful that the police box system is not overdone.”

Post-war, policing would begin to change again, with smaller district police stations re-established for the new suburbs. As was the case after its 1920 expansion, it was found once again that the city had “more or less outgrown the numbered strength of the police force“. This was particularly felt in the extensive housing schemes been built since the boxes were introduced and where petty crime and antisocial behaviour were an increasing problem. After the initial roll-out of boxes, too few had been added. For instance, in 1946 just one was approved for the West Pilton housing scheme at the junction of Ferry Road Drive and West Pilton Avenue. The peripheral estates were harder to police on foot as they had a much lower housing density than the inner city, so officers had a far greater distance to cover.

New council housing at the Inch, 1955, Dinmont Drive. Photograph by A. G. Ingram, © Edinburgh City LibrariesThese issues saw a move in the 1950s away from the “box and beat” approach to policing the suburbs to more mechanisation (cars) and technology (walkie talkies). They continued in use for the centre of the city however, but the last box installed in Edinburgh may have been that erected in Davidson’s Mains in 1958.

It is all very nice to see policemen going their rounds, but in these days of radio telegraphy the greatly increased use of telephones and the system of 999 calls it is quite reasonable to expect that there should be some saving in the actual pedestrian work

Bailie Matt A. Murray, Chairman of the Progressive Group of Edinburgh Town Council

The air raid warning system was renewed and expanded in 1952 with 56 sirens refurbished, ten additional ones installed and the remote control system replaced. The signalling was replaced again in the 1960s and the sirens were replaced in the early 1970s. Just before 1pm on Thursday 5th June 1969, the air raid sirens sounded across Edinburgh as an engineer working at the city Police headquarters on the High Street accidentally activated the system. A similar incident occurred on August 1st 1986 when all sirens in the Lothian & Borders Police areas were accidentally activated at 7:30 in the morning due to a fault in the telephone system.

Just as Edinburgh had been slow to catch on to adopting police boxes, it was also slow to let them go. While the Metropolitan police started removing boxes in 1969 and demolished its last in 1981, those in Edinburgh were still nominally in active service into the 1990s. After 1984 however the Chief Constable wanted all officers to have a daily briefing at a station before they came on duty and so after then they were more rarely used and many that were found themselves relegated to providing shelter and storage for traffic wardens. In 1993 the air raid sirens were deactivated by the Scottish Office and in 1995 the Lothian & Borders Police Board deemed thirty five of the eighty six remaining boxes were surplus to requirements and put them up for auction, seeking to save the £500 per annum per box maintenance costs of the increasingly dilapidated estate.

Newspaper advert, Scotsman, June 13th 1995, advertising the sale of 35 surplus police boxesThese were the first boxes maid available on the open market and generated much interest; a variety of proposals from public toilets to newspaper kiosks to air quality monitoring stations to removing the boxes entirely to install them as curios in pubs or people’s gardens were proposed. In 1990, the predecessor of Historic Environment Scotland listed thirteen boxes as Category B to protect them (there are now a total of seventeen) and the city’s Planning Convenor would issue guidelines requiring any changes to the boxes or their interiors needing planning permission.

Former lawyer Gordon Thomson purchased eight boxes and, as American-style coffee drinking swept across the nation, established a small chain of bijou “cappuccino kiosks” called the California Coffee Company. Thomson may not have realised it, but his innovation was very close to recreating a street scene once common in 18th century Edinburgh. A 2000 attempt by Feyzullah Marasli to emulate this success by converting a box on Princes Street into a coffee kiosk came to nothing when it was discovered that despite him refurbishing the box, changing the locks on it, paying £400 to have an electricity supply installed and applying for the necessary Street Trader’s Licence, he neither owned nor leased the box in question and it was still in operational use by the Police!

‘A street coffee house Edinburgh’. Paul Sandby, 1750s, Royal Collection Trust RCIN 914503Lothian & Borders Police attempted to rehabilitate some boxes in the late 1990s by installing touch screen public information points with a video-link to a police station within them. The first such box was unveiled to the press on Princes Street in 1998 at a cost of £10,000. It had 61,000 “hits” during its first year of operation and was judged to have been a success, with two further such boxes converted, however funding never followed through and the innovation was allowed to lapse.

Eleven more boxes were auctioned in 2001, advertised as “an exciting and unique opportunity to obtain a distinctive piece of cast iron street furniture with potential for a wide range of uses“. In 2002, the BBC successfully trademarked the London-style Police Box in connection with Dr. Who and the TARDIS, despite the Metropolitan Police contesting the application with the Registrar of Trade Marks. This did not apply to Edinburgh’s unique boxes, which are categorically not TARDISes, despite what some may say! From 2012 to 2013, the police box at Braid Hills Approach was restored to exhibition standard as a small museum by Angus Self, a great grandson of Chief Constable Roderick Ross. In 2014, fourteen of the remaining boxes were sold off, leaving just one in Police ownership.

‘SwimEasy’ Police Box Museum, Braid Hills Road. CC-by-NC SA 2.0, M J RichardsonThe boxes may now be entirely operationally defunct, but they remain throughout the city and many are in daily use. In fact I’m just back from visiting one this afternoon, It may not be a TARDIS but an architectural time traveller it was!

Late night Brazilian crepes anyone? A police box has you covered… CC-by-NC 2.0, Joe Gordon via FlickrIf you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#architecture #CityArchitect #EbenezerJamesMacrae #Police #PoliceBox #Policing #RoderickRoss #StreetFurniture #Written2025