The thread about the King’s Botanist, a bungled attempt to capture Edinburgh Castle and death by “surfeit of figs”

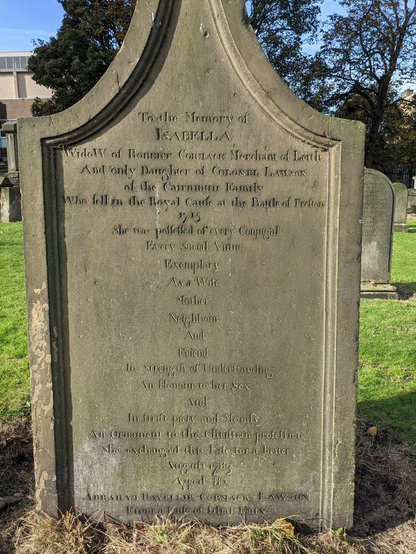

Today’s 18th century historical thread starts with a chance photo of a gravestone in South Leith Kirkyard, taken because of the touching eulogy on it. Who was Isabella? And who was Colonel Lawson? I thought I would try my hand at finding out, not realising the remarkable yarn that would be spun from this search, largely because a few errors on the stone which made me dig deeper than I probably otherwise would have in trying to resolve them.

To the Memory of ISABELLA, Widow of Robert Cormack, Merchant of Leith and Only Daughter of Colonel Laswson Who fell in the Royal Cause at the Battle of Preston 1715…She exchanged this Life for a better, August 1783, Aged 82.

Abraham Davellie Cormack Lawson [her son]

I started my search with Isabella. Isabella Lawson (1700-1783) was the daughter of Janet Wilson and James Lawson of Cairnmuir. The Cairnmuirs were minor Borders gentry, their seat was Cairnmuir House – also known as Baddinsgill – near West Linton.

My eye had been caught at first by the eulogy. Someone else’s was caught by the phrase “Battle of Preston 1715” and whether “in the Royal Cause” meant they were on the side of the House of Stuart or that of Hanover; after all, both were Royal Causes. So I tried to find that out too out. I eventually found that our Lawson was in Colonel Preston’s Regiment of Foot later known as the 26th and better known as The Cameronians and that he was actually of the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. The Cameronians were an unusual regiment which could trace their descent directly from the Covenanting (Scottish Presbyterian) movement. They were formed by the Convention of Estates (a sister institution to the Scottish parliament) in 1689 to defend the Presbyterian settlement in the country as a result of the “Glorious Revolution” from Stuart attempts to impose Episcopalianism. As such they were explicitly anti-Jacobite and had proved loyal to the Houses of Orange and later Hanover. It was The Cameronians who, at the Battle of Dunkeld, had put down the Jacobite rebellion of 1689 and as such we can be sure that Lt. Col. Lawson fought on the side of the Hanoverians at Preston.

Cameronian soldiers in the uniform of 1713This is where we get to the errors on the gravestone. Firstly, and as far as I can verify, Lt. Col. Lawson did not die at Preston at all. The regimental history acknowledges he was in action at the battle and was badly wounded, but his death is actually recorded 3 years later in 1718. Whether that was from injuries which he had sustained we cannot be sure, and this may have been the case as The Cameronians took a lot of punishment. Secondly, Isabella Lawson was not his only daughter! She may be the only daughter of his wife Janet Wilson, but the Lt. Col. has at least 6 other children by another wife – Marion Reoch. The chronology of births is confusing as to which were by Marion and which by Janet. But I think we can forgive the errors here as the stone, by its own admission, was erected by Isabella’s son – Abraham Davellie Cormack (isn’t that a wonderful name?) – some 70 years after the facts and details may have gotten lost in family stories.

This is all interesting enough in its own right, but on digging around the family tree to try and resolve these questions it brings up Lt. Col. Lawson’s older brother; John Lawson of Cairnmuir, Esq. (1657-1704). It’s not John who is so interesting, it is his wife, Barbara Clerk (1679-1734). Barbara is the daughter of Sir John Clerk of Penicuik and her brother is Sir John Clerk of Penicuik (better known as “Baron Clerk” to differentiate him from his father). The Clerks are one of the most powerful and influential families in the early 18th c. Scottish establishment. Baron Clerk is the Whig’s Whig, a strong supporter of the Union of Scotland and England, a Commissioner for the Union of Parliaments, a Whig MP in the first parliament of Great Britain and later Baron of the Exchequer for Scotland.

Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, (Baron Clerk) by William AikmanBarbara’s first husband, John Lawson, was therefore a fitting match. From the correct class of Lowland gentry like herself, with the correct political leanings and a brother-in-law in the service of one the Government’s most loyal regiments. But when John dies in 1704, it is Barbara’s second husband where things begin to get really interesting. On the 21 February 1710, Barbara marries one William Arthur* , M.D. (* = no relation, as far as I can tell!) William was born in Elie in Fife in 1680, his father was Patrick Arthur of Ballone, a surgeon, apothecary and Commissioner of Supply for Fifeshire. The Commissioners of Supply were local bodies in Scotland responsible for certain aspects of civic administration. William’s mother is Margaret Sharp, a relative of the recently assassinated episcopalian Archbishop Sharp of St. Andrews. So, on paper, William also comes from the right sort of family for a union with a Clerk. In 1701 or therabouts, William travelled to Utrecht to study medicine under Herman Boerhaave, “the father of physiology“. This was about the best place he could of gone to study medicine in Europe at the time, so clearly the Arthur’s had high aspirations for their son and the means to pursue them.

Herman BoerhaaveWilliam returned to Scotland in 1707 as Dr. Arthur and began to practice medicine with his father in Fife. It is probably through chance that he treated Baron Clerk – who was on a hunting trip in Fife – and becomes acquainted with the latter’s widowed sister, Barbara. The match was obviously approved and as a result the aspiring Doctor finds himself ingratiated into one of the best-connected families in the land. This begins to pay dividends for his career and in 1713 he was licensed to practice medicine in Edinburgh by being invited to join the Royal College of Physicians. He was made fellow by 1714. Dr. Arthur finds himself rubbing shoulders with – and treating – the great and the good of Edinburgh society. All is going well in the Arthur-Clerk household and it’s about to get even better, albeit briefly.

Fountain Close in Edinburgh in 1853, little changed from Dr. Arthur’s day more than a century earlier when the Royal College of Physicians was based hereIn 1714 the ailing Queen Anne dies and in her place comes His Most Serene Highness George Louis, Archbannerbearer of the Holy Roman Empire and Prince-Elector, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg; King George I to you and me. One of the new King’s more unusual initial duties is to choose a Regius (Royal) Keeper for the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, as that was a direct household appointment of the Monarch, and became vacant at the point of Queen Anne’s death. The garden at this time located in the Nor’ Loch valley, where Waverley Station is today.

Edgar’s Town Plan of 1765, showing the Physick Garden – note the hed of the Nor’ Loch to the left of themap, to the left of the block designated “S” (which was the first pier under construction of the new North Bridge). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe incumbent keeper since 1676 is James Sutherland, re-appointed by Queen Anne in 1699 and holder of the Chair of Botany at the university. It would therefore seem sensible that the capable, experienced, renowned and well thought of Sutherland would be re-appointed. But no, it’s not what you know but who you know. For reasons that we can only assume to be Baron Clerk’s influence, William Arthur – whose knowledge of botany would have extended only to a physician’s herbs – finds himself not just the Regius Keeper of the Botanic Garden but also the King’s Botanist, by royal appointment.

A catalogue of the plant collection at the Physick Garden, published by James Sutherland © Royal Collection TrustTo paraphrase Bayley Balfour, biographer of the Regius Keepers, Dr. Arthur probably knew nothing about botany and certainly made little to no contribution to it or to the garden in his charge during his tenure. However he hardly had a chance to, as we are about to find out.

It is now 1715, and all is not well in the land and not everyone is that thrilled with the new king. Long story short, on 27th August that year John Erskine, Earl of Mar, took it upon himself to raise the Jacobite Standard for the exiled Pretender” James Francis Edward Stuart at Braemar and with 600 men called the Jacobite loyal to arms. Up until this point, Mar had been in the service of the Government and his nickname is “Bobbing John” on account of his reputation for dithering and it never being clear quite which side he is actually on at any given time.

Raising the Jacobite standard at Braemar. From “Cassell’s History of England”, 1906Mar’s forces swell to 20,000 and quickly take control of much of Scotland north of the Forth. Much of Bobbing John’s early success may have been at the hands of subordinates taking initiative. But sites are now set on Edinburgh and its Castle. Within the Castle are government arms enough for 10,000 men and £100,000 that was paid to Scotland upon the Union with England. This plan may have been the instigation of James Drummond (later 2nd Duke of Perth); a Stuart loyalist who had been with James II when he lost his chance of the crown in Ireland.

James Drummond, 2nd Duke of Perth, in 1700 by Sir John Baptiste de Medina. Note the slave boy in the painting, who wears a locked collar and a uniform jacket, denoting him as the property and servant of the Duke.Edinburgh Castle would be a tough nut to crack. It’s easiest to bypass it entirely and leave it isolated and relatively impotent up on its rock – but when you want what is in it that is not an option. It had been demonstrated that it could be reduced by siege and force as the English did in the Lang Seige of 1573, but the Jacobites had neither the men, resources, time or artillery for that.

“Scene from the Lang Siege” from the Hollinshead Chronicle. Edinburgh Castle on its rock is entirely surrounded by a besieging English army and its Scottish protestant allies.”No, the best and easiest way to take it was by sneak or subterfuge. Thomas Randolph had done this for Robert the Bruce. Alexander Leslie had done it for the Covenanters. Who was going to do it for King James VIII of Scotland and III of England? Step forward, for reasons known only to himself, Dr. William Arthur, Regius Keeper of the Botanic Garden and King’s Botanist.

What follows is my interpretation of events – I know others exist and you can read them elsewhere.

It is reputed that the Arthurs may have been Jacobites – after all his mother was a relative of an important episcopalian archbishop – but that may be hearsay. Whatever the reason he got involved, William at least had the perfect cover; he was married into an unimpeachable family, was in an intimate position in the depths of the pro-Hanoverian Scottish establishment and was a personal appointee of the King.

Dr. William has a brother, Major Thomas Arthur of the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards (the Royal Scots to you and me). The brothers have a cousin (or he may be a younger brother), Lieutenant James Arthur in the Edinburgh Regiment of Foot (The King’s Own Scottish Borderers to you and me). The Arthurs got to work on a plan to take the castle by derring-do, in which the Doctor’s role seems to have been one of coordinator and fixer. Arms were to be assembled, 30 muskets with bayonets and a “great many” small arms. These were cached in the house in the Potterrow of Sir David Murray of Stanhope by his wife. Recruits were found within the Jacobite sympathisers in the city; from dispossessed Jacobite officers, lawyers, clerks, apprentices and “other youths of a class considerably above the mere vulgar“. We will come back to these latter young men later.

Lt. James promised 30 loyal, armed grenadiers from within the Edinburgh Regiment, they were just awaiting the word. Major Thomas sounds out potential sympathisers and collaborators within the castle itself. Eventually three men, a Sergeant and two Privates, are trustworthy enough to be bribed to assist. From the Duke of Perth are sent 50 loyal men of the Highlands, to be led by Alexander Drummond of Bahaldie – “a gentleman of great courage“. Drummond’s real name is Alexander Macgregor, and he is chieftain of Clan Gregor, whose name is forfeit. The last piece of the arrangements is Charles Forbes. On the face of things a down-on-his-luck local merchant, but apparently actually a Jacobite agent. Forbes is engaged to build foldable assault ladders and to have them ready for a surprise, night-time assault on the Castle walls. Things quickly begin to go wrong however; Major Thomas’ wife got word of her husband’s dealings out of him and she is able to forewarn Sir Adam Cockburn of Ormiston, the Lord Justice-Clerk and 2nd most powerful man in the Scottish legal system, of the threat. Ormiston, inexplicably, ignored the warning and so the Arthurs might still have been in with the element of surprise.

Adam Cockburn (1656-1735), Lord Ormiston. By William Aikman. Cc-by-SA National Galleries ScotlandBut remember those Jacobite youths of the “class considerably above the mere vulgar“?. Well they got bored with waiting around for the word and they went and got drunk in a tavern. While they were “powdering their perriwigs in preparation” they give the game loudly away to anyone with ears. Word was again sent to Adam Cockburn of Ormiston. This time he decided to do something about it and a messenger is sent to the Castle where, eventually, the deputy governor is roused. Sceptical, he gives instructions to double the guard and goes back to his bed. Yet again, the Arthurs might still be in luck. At 11 o’clock at night, on what was probably the 9th or 10th of September 1715, the raiding party assembled in the kirkyard of the West Kirk (now known as St. Cuthbert’s), below the sheer face of the Castle Rock.

The West Kirk in the 18th century, from Old & New Edinburgh by James GrantTheir target was the Castle on top of said rock, towering overhead. And up they went, picking their way in the dark of night up the treacherous paths scraped into the cliff face. Perhaps luck was on their side, as miraculously they made it to the top and the foot of the walls on schedule and without issue.

Edinburgh Castle towering above St. Cuthbert’s Graveyard. James Skene 1818, © Edinburgh City LibrariesAt the arranged time and place, they were able to make contact with the bribed Sergeant, on duty on the battlements above.But that is where the luck ran out and two problems now manifested themselves. Firstly, the Sergeant is due to be imminently relieved early as a result of the Governor changing the pattern of the guards on account of Ormiston’s warning. Secondly, Charles Forbes and his ladders are nowhere to be seen. The party have only a single rope ladder and grapnel among them. Pressed by time and circumstances, and the ever-more desperate Sergeant up above, the leader of the Highlanders – Drummond of Bahaldie – took control of matters. He threw up the rope ladder and convinces the Sergeant to make it fast and drop it back down; alas, it proves to be at least a fathom too short.

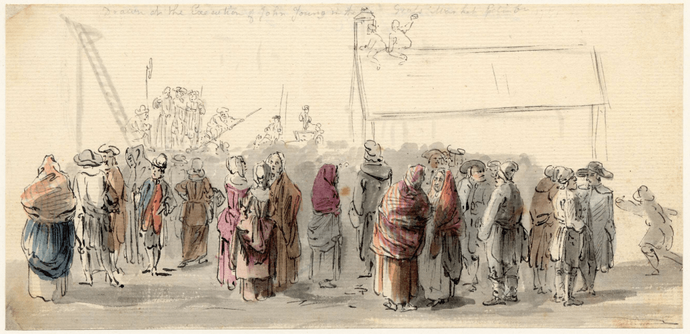

And then the Sergeant’s relief arrived and the game was up! Trying to save his own skin, he called out “enemy!” and fired his musket into the darkness. But the rope, which could only have been affixed to the walls by himself, gave his treachery away and he was quickly apprehended. An illustration made to celebrate the Hanoverians’ eventual victory in the 1715 rising describes the moment that the rumbled Jacobites fled in all directions.

“Attempt to Surprise Edinburgh Castle”, a scene from “Sheriffmuir 1715. March of the King’s Forces and cannon to Perth” by Terrason. CC-by-NC, National Galleries ScotlandOne of the Jacobite party, an old officer by the name of Maclean, fell on the rocks as he fled and was apprehended. The rest of the Highlanders under Drummond of Bahaldie – with Major Thomas Arthur in company – headed north to rejoin with Mar and apparently didn’t stop until they got to Kinross. Of the local contingent, three of the indiscreet youths scatter one way, finding what they thought were friends coming the other. Only it wasn’t friends but none other than the Town Guard, turned out on the initiative of Adam Ormiston. The others worked their way around the the north bank of the Nor’ Loch, through the area known then as the Barefoot’s Park. Here, they ran into a man heading the other way encumbered under a load of folding ladders… it was the delayed, incompetent or double-crossing Charles Forbes.

The Barefoot’s Park from the Castle in 1750 by Paul Sandby, with the corner of its walls on the left. The is looking north, with the partially drained swamp of the Nor’ Loch in the valley below. The Jacobites would have fled around this area. The line of walls is the Lang Dykes, an old roadway approximately on the line of Princes Street.Dr. William Arthur was not part of the raiding party, but eventually decided to go to the Castle Rock for himself at some point that night to find out what had become of the assault. He found only a discarded musket and the Town Guard and Castle Garrison in a state of frenetic activity. He fled to try to find some of the other conspirators, eventually crossing their path. On finding out that all was lost, he saddled his horse and fled south from the city with the others. William will later recount in a letter later, sent on his deathbed to the Earl of Mar, that he didn’t stop until he got to Polton in Midlothian and the house of a niece. Here he and a number of the gentlemen conspirators with him got provisions and fresh horses, before striking out over the Pentlands.

Back in Edinburgh, the luckless Sergeant was thrown in the brig, court-martialled, found guilty and duly hanged. The Deputy Governor of the Castle, who had gone back to bed, was relieved of his duties and imprisoned for a time. In the cold light of morning, William Arthur’s brother-in-law, Baron Clerk – accompanied by Adam Ormiston and others – came knocking at his door to enquire where he might be. The lady of the house, his sister Barbara, was none the wiser. William by this time has made it over the Pentlands to the house of his aunt’s wife. He has travelled faster than the news, so his relation has no cause to suspect him and again he is given refuge. He wrote off a quick letter to Barbara in Edinburgh and stayed long enough to receive an answer that informs him that his part in the conspiracy is known and he is a wanted man. He once again gets fresh horses and flees. Now, do you remember the Lawsons of Cairnsmuir from the gravestone, the Laird of which was his wife’s first husband? Well, as part of the settlement after his death she had come into possession of various parts of his estate. As husband of the mistress, William will be welcome there so long as he can ride faster than the news travels, so makes his way south and back across the Pentlands, and is able to acquire, supplies, money and – once again – fresh horses. And once again, he flees; so long as he keeps moving away from Edinburgh he might just be able to escape.

William would later claim to Mar that he fled into the Borders as he thought he might be “of service” to the cause there. Indeed, there was a failed attempt by a Jacobite party under Mackintosh of Borlum to organise rebellion in this area and he may have made contact with it. But whatever his intentions, Jacobite sympathisers in Teviotdale saw him smuggled over the border to somewhere in Northumberland – although from his letter it may have been that he didn’t actually know where we was! He now disappears for a while. The authorities back in Edinburgh claim that he and a cousin, William Barnes, had met up again with Mar to provide him with intelligence and had been present at the Battle of Preston in October 1715 where the Jacobites would surrender and the doomed rebellion would fail.

The Jacobites surrender to General Wills at Preston, © Harris Museum & Art Gallery, PrestonThis takes us full circle and back rather neatly to where we started, as who else was at Preston (on the victorious side) but that name on the gravestone, Lt. Col. James Lawson of Cairnsmuir; brother-in-law to William Arthur’s wife through her first marriage. The Jacobite Pretender, James Francis Edward Stuart, would land in Scotland at Peterhead all too late in December 1715, and would be back on his way to exile at the start of February the following year. In his wake would follow various other Jacobite gentlemen and officers; including William Arthur would next surface in Rome a few months later in 1716.

The Pretender and his companions flee Scotland in 1716, a scene from “Sheriffmuir 1715. March of the King’s Forces and cannon to Perth” by Terrason. CC-by-NC, National Galleries ScotlandHere, he set about writing a lengthy letter to the Earl of Mar – himself exiled in Paris – as to why he had failed in his task and why it wasn’t his fault. It is while drafting these excuses, that William consumed a “surfeit of figs”, caught dysentery and died as a result. Perhaps a slightly ironic way for a King’s Botanist to go out; but William was a botanist only in name and thanks only to the patronage of a King he had quickly betrayed. From his death bed, he passed his letter to a Jacobite agent, Dr. Roger Kenyon, who conveys it and news of Wiliam’s death to Mar in Paris. Arthur was clearly popular in Rome as sympathisers organised an elaborate funeral with special permission given by Filippo Gaultieri, Cardinal-Protector for Scotland, according him as a protestant the rare privilege of being buried within the walls of that city. This would become the Cimitero dei Protestant – Protestant Cemetery.

Filippo Gaultieri, Cardinal-Protector for ScotlandAnd that wasn’t even the end of the silliness of the Jacobites in their attempts to take Edinburgh, because they soon tried again! (And one again, Major Thomas Arthur was involved and once again the attempt failed due to incompetence). So if you liked this story, you’ll definitely like the The thread about Brigadier Mackintosh of Borlum; the Jacobite uprising of 1715 in Edinburgh and Leith; and the wacky tale of its military incompetence.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#1715 #Arthur #BotanicGarden #Castle #EdinburghCastle #Jacobites #NavalMilitary #PhysickGarden #September9 #Written2021