↕️ Renverse.co ↕️ STILL WE'LL RISE : CINÉMA ET LUTTES CONTRE LA VIOLENCE POLICIÈRE: STILL WE'LL RISE, cycle de films sur violences policières et résistances. Au cinéma Spoutnik, 11 rue de la Coulouvrenière : 17.09, 26.09,… #ViolencePolicière #Résistance #Cinéma #CulturalResistance #JusticePourTous

STILL WE'LL RISE : CINÉMA ET L...

#culturalresistance

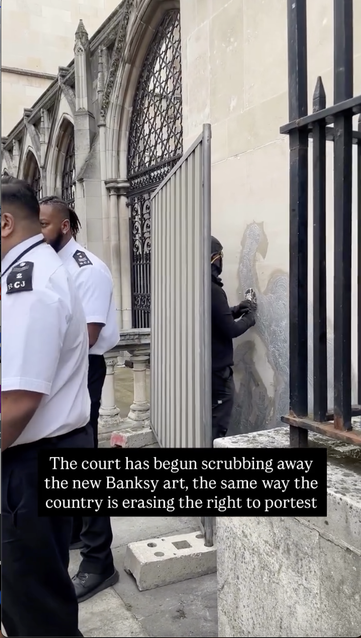

That’s why it deeply unsettles me to see how quickly Banksy’s graffiti on the Royal Courts of Justice was erased—a bold, incisive image of the structural injustice of the judicial system and the arbitrariness of institutional power. Although I have always admired British artistic irreverence, today my disappointment mixes with anger. Erasing Banksy is a stab at the creative heart of those who believe street art is resistance, not vandalism or crime. Banksy (whoever he or they may be) is pure hacking.

He is accused of “criminal damage to public property,” but the real crime is committed by authorities when they erase art, attack popular culture, suppress freedom of expression, and deny public spaces the chance to evolve and be reimagined in dialogue with our times. Would they have dared to erase a Turner or Hogarth mural, cross out a Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud piece, or destroy a sculpture by Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth?

While architectural or artistic interventions are applauded when directed, and controlled by authorities (many hideous and meaningless), any spontaneous expression that dialogues with the city, questions power, or redefines public space is labeled vandalism.

Where is freedom? Where is the possibility for art to evolve with society and transform our present? Erasing Banksy is not protecting history; it is freezing it, silencing it, and denying that public spaces can also be places of critical thinking and creativity.

#Banksy #Art #ArtAgainstCensorship #Graffiti #Hacking #FreedomOfExpression #CulturalResistance #Censorship

Haitian performers fight back through dance http://newsfeed.facilit8.network/TMqPvW #Haiti #Dance #Vodou #PerformingArts #CulturalResistance

Forum for African Women Educationalists

Author(s): Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Publication (Outlet/Website): The Good Men Project

Publication Date (yyyy/mm/dd): 2025/05/29

Teresa Omondi-Adeitan, Deputy Executive Director of FAWE, discusses women’s leadership in Africa at CSW69. Despite international agreements like the Maputo Protocol mandating gender parity, implementation remains weak due to cultural and political resistance. Rwanda exemplifies deliberate leadership in women’s inclusion, but many nations lack enforcement. Economic arguments have proven effective in convincing male leaders of the benefits of gender equality. FAWE emphasizes early leadership training for girls and boys to normalize women’s leadership. Challenges persist, including campaign financing and election-related gender violence, but institutionalizing gender equity, rather than relying on individual leaders, is essential for lasting progress.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: Name and title.

Teresa Omondi-Adeitan: My name is Teresa Omondi-Adeitan. I’m the Deputy Executive Director of the Forum for African Women Educationalists, commonly known as FAWE.

Jacobsen: Today, we are at the 68th session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW68), marking Beijing+30 and the 25th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security. It’s a significant year for these discussions.

Recently, we have seen political shifts, particularly within the American administration and among other political leaders, including autocrats, who view these developments as beneficial to their agendas. However, these changes are not favourable for women globally in terms of political representation, economic participation, and gender parity in general.

First, taking a broad perspective, what has been your major takeaway from this particular Commission compared to previous ones?

Omondi-Adeitan: This is an important commission because this year marks 30 years since the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. That conference is especially significant because it led to adopting the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which remains a comprehensive framework for advancing gender equality. Many of the women’s rights we enjoy today are based on that declaration and the commitments made by governments worldwide.

It is inspiring to walk into this conference and see some women present at the Beijing Conference still championing gender equality and pushing for advancements in political, economic, social, and cultural participation.

Being here during this conference is about evaluating our progress. How far have we come? Have we achieved the commitments made 30 years ago? Are we living up to the promises made by those who came before us?

At the same time, I have observed significant setbacks. Progress often feels like taking one step forward and two steps back. The question I keep asking is: What is going wrong? Why are we unable to sustain the gains we have made?

This conference has been particularly valuable because I have had the opportunity to hear perspectives from different countries. These discussions are shaping my thinking, especially as the Deputy Executive Director of FAWE. They are prompting me to reconsider our approaches and strategies for achieving and maintaining women’s rights.

Jacobsen: We just came from a session in the Church Center for the United Nations (CCUN) on the eighth floor. One thing that stood out was the striking similarity in shared stories. They were not identical, but regardless of the country or whether someone comes from a background of disability or not, the emotions and words used to describe the current situation were remarkably similar. There is a clear sense that we are in a period of pushback. When reflecting on that pushback in the context of FAWE’s programs, what are you considering for the sustainability of those programs and the efforts they advance?

Omondi-Adeitan: We discussed women’s participation in politics in the session we just attended. At FAWE, we recognize that early intervention is crucial. Too often, women are expected to run for political office or serve in public leadership roles without prior exposure to leadership experiences.

As an education-focused organization, we aim to empower girls and women through education in Africa. Leadership development must start early, equipping young girls with the skills, confidence, and knowledge necessary to step into leadership roles later in life.

We are using the education system to teach girls early on to become leaders. As early as five years old, a child can begin serving as a class prefect or class president, depending on the terminology used in different countries. They can already be given responsibilities in grade six or seven. By the time they reach grade nine, they may even lead a school as a school president.

This way, when they get to university and beyond, and someone approaches them with a leadership opportunity, they are ready because they have already gained experience. In many parts of Africa, particularly among women, leadership exposure often comes only after completing university. The common refrain has been, “Oh, but there is this position, but no women are interested.” It is not that women are uninterested, but rather that this is the first time they are told they can lead. Too often, they are quickly processed or hastily trained for leadership at the last moment.

At FAWE, we aim to change this by creating a pool of young women prepared for leadership roles from an early age. It can be as simple as being a class monitor responsible for taking books to the teacher for marking, leading the Girl Guides in school, or heading the debate club. These small responsibilities help normalize leadership so that when greateropportunities arise, it is neither a surprise nor an overwhelming challenge. Our approach within the education sector is to embed leadership training early, ensuring that young women are already equipped with the necessary skills when they enter public life.

We hope this will increase the number of women willing to enter public leadership. When young girls start experiencing criticism early on, they become more resilient. By the time they face the more intense scrutiny that comes with public leadership, they will have already toughened up and know what to expect.

Jacobsen: One critical aspect of leadership is skill-building. In a session I attended a few days ago, a European delegate noted that women are often over-mentored but underprovided with opportunities in their cultural context. They receive extensive guidance but are not given the actual chance to lead. The question then becomes: How do we balance early leadership opportunities with continued mentorship so that young women receive training and have real platforms to exercise their skills?

Omondi-Adeitan: There are two primary public spaces for leadership. One is within government institutions, such as serving as a minister, a permanent secretary, or a leader in a state-owned corporation. This type of leadership does not require substantial financial resources but depends on skills, positioning, and opportunities. However, the most persistent challenge remains political leadership. We all know that running for office requires resources, and that is where many women face significant barriers.

There is bribery, issues of positioning, and many other challenges. Women often lack the financial resources needed to run effective campaigns, leading to what some call being “over-skilled.” These women have the expertise and are mentors, but they cannot afford a campaign tracker, campaign T-shirts, or television advertisements to promote their candidacy. I have heard this concern repeatedly.

At the same time, development partners who advocate for women in leadership are often unwilling to fund essential campaign expenses, such as fuel for campaign vehicles, advertising costs, or campaign materials like T-shirts. I have worked in contexts where we had to be creative with available resources. If a development partner provides funding for a workshop to train women instead of only producing standard information, education, and communication (IEC) materials, we can also use that opportunity to create campaign T-shirts. This is simply the reality of the political landscape—while it is possible to tell women that they do not need T-shirts to campaign, their male counterparts will be everywhere with banners, posters, and branded materials. Women candidates cannot afford to be left behind in visibility.

This is how we are innovative with development partner funding while organizing efforts to secure direct campaign financing. Running a political campaign is extremely expensive in Africa. In theory, Campaign finance regulations exist but are among the least enforced. There are legal limits on campaign spending, but these limits are routinely ignored, and little is done to address violations, especially during election periods.

Beyond financial barriers, women also face election-related gender-based violence. During campaign seasons, women struggle the most to access financial support and campaign platforms. It is also the time when they are reminded of their family roles and their supposed “feminine nature,” often as a tactic to discourage them from running. Even when a woman has the opportunity to stand as a candidate, she must also navigate these societal pressures and cultural barriers.

I completely understand and agree with women who say they feel over-skilled but lack the resources to compete effectively.

Jacobsen: It is like football—one may have the skills to play, but if they are competing against a team that has proper gear, including socks, boots, and training facilities, while they have none, it will never be a fair competition. It is a bit like a Tom Brady situation—being highly skilled but unable to access the necessary resources, forcing one to take work elsewhere, like at T-Mobile.

One of the most surprising things I learned from that session was that Africa has both the lowest and the highest rates of political participation among women. The variance in participation across the continent is striking. Why is that?

Omondi-Adeitan: The type of leadership and the deliberate efforts of those in power play a critical role. Rwanda, for example, constantly sets the benchmark for Africa, as it has the highest percentage of women in parliament worldwide. However, this is not just about numbers—it is about the type of leadership and the purposeful, deliberate inclusion of women. President Paul Kagame has intentionally integrated women into leadership at all levels. His approach is strategic, from appointing women to his cabinet to ensuring strong female representation in parliament and public office.

Finding similarly deliberate leaders across Africa remains a challenge. Why is this level of intention necessary? The answer lies in deep-seated socio-cultural norms. Many African societies have long been structured around male dominance in leadership. If a male leader is already in power, it often requires significant resources to shift his perception before he can even consider appointing women to his cabinet or other leadership positions. Research has confirmed that Rwanda’s success is not just about having policies—it is about the political will of the country’s leadership to implement those policies.

Most African nations have policies mandating at least 30% female representation in government. However, implementation is inconsistent. Achieving gender parity requires a deliberate commitment from the highest levels of leadership. Without strong political will, these quotas remain theoretical rather than practical.

Jacobsen: Which country has the lowest level of political participation, and what is the key factor behind it?

Omondi-Adeitan: The biggest factor is cultural and religious influence. In some regions, religion plays a major role in shaping leadership norms. Certain interpretations of religious doctrines, whether in Islam or Christianity, reinforce the belief that women should not hold leadership positions.

For example, countries with dominant Islamic or Catholic populations tend to have lower female political participation. However, the extent of women’s exclusion depends on how religion and culture intersect in different societies. It is not about the faith but how leadership roles are perceived within these religious frameworks.

I know of a community in Kenya where male leaders formally convened a conference and collectively declared that their culture does not permit women to lead. They refused to support a female candidate, not because she lacked qualifications, but because leadership had always been seen as a male role. They eventually accepted a woman in office because the law required them to elect a female representative. So, what happens in such situations?

Continuous sensitization and engagement are necessary for young people because their perceptions are already shifting. They are growing up in a slightly different cultural environment and are adapting more quickly to global norms.

You previously asked Senator Reddy Kengueve about economics as the key factor, suggesting everything else flows from economic independence. Your question made sense, but our discussion now highlights that religion and traditionalism play an equally significant role. Economic independence is crucial, but deep-rooted religious and cultural traditions can sometimes outweigh economic considerations in determining women’s access to leadership.

Jacobsen: What about policy and law? If a strong policy or law is in place, does that guarantee change, or is implementation still a major obstacle?

Omondi-Adeitan: As I mentioned earlier, most African countries already have policies promoting women’s representation. I do not have the exact statistics, but almost every African country has a 30% female leadership quota. In theory, the framework is there. The problem is implementation and genuine commitment to enforcing these policies.

Take the Maputo Protocol, for example—the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on Women’s Rights in Africa. This protocol mandates equal representation and explicitly calls for 50/50 gender parity. Almost all African nations have signed it, with only a few exceptions. Yet, despite this formal commitment, gender parity in political representation remains elusive.

So, the real question is: If African countries have signed these agreements and adopted gender quotas, why is representation still so low? The answer is that policy alone does not guarantee change. It comes down to leadership and political will. The leaders in power decide whether or not policies are fully implemented.

For example, if a president sees that an election has resulted in less than 30% female representation, they should take steps to nominate additional women to meet the quota. However, if the leadership lacks the commitment to act, the policy remains meaningless.

Look at Botswana and Rwanda—two countries that have excelled in women’s political representation. Their success is not just due to laws but to leaders who actively enforce those laws. The problem is that leadership enforcement should not be necessary—the law itself should be enough. Unfortunately, in many cases, the implementation of gender policies depends on the goodwill of an individual leader rather than a systemic commitment to gender equality.

This raises an important concern: What happens when a strong leader leaves office? For example, President Kagame of Rwanda has deliberated on promoting women’s leadership. But if something happened to him, would Rwanda’s gender progress be sustained, or would it regress? These are the challenges we face—ensuring that gender equality is embedded institutionally, not just dependent on individual leaders.

Regarding laws and policies, most African countries are already clear on women’s representation. They have signed international protocols and legislation beyond national constitutions, committing to gender equality on paper.

Jacobsen: If the linchpin of change is leadership, and the individuals with the most political control and decision-making power are men, what has been the catalyst for shifting the mentality of those men who have demonstrated the political will to align with the Maputo Protocol and existing gender policies?

Omondi-Adeitan: One of the biggest catalysts for changing male leaders’ perspectives has been demonstrating the economic benefits of having women in leadership. We have learned—especially in Kenya—that the most effective way to convince governments to support women’s representation is to translate gender equality into economic value.

When women’s leadership is framed in economic terms, governments stop and listen. This is how we secured the women’s representation seats in Kenya. Unfortunately, the reality is that money talks, and when gender equality is shown to be economically beneficial, male leaders are more likely to take action.

No country can afford to leave half its population behind and still expect strong economic growth. The evidence is clear—economies that actively include women in leadership perform better than those that do not. That economic proof has been a key strategy for influencing decision-makers.

Beyond policy advocacy, FAWE believes in starting early. We do not only work with girls—we also engage boys to normalize women’s leadership from a young age. If we instill these values early, future generations will not have to fight the same battles.

I want to believe that by the time my 11-year-old daughter and my 4-year-old daughter reach my age, their struggles will be different. Their debates will no longer be about whether women deserve a seat at the table—instead, they will engage in intellectual discussions about policy and governance rather than basic representation.

We are working hard to change perceptions early so that the next generation does not have to fight for what should already be accepted.

Jacobsen: Thank you for your time.

Omondi-Adeitan: Thanks, I appreciate it.

Last updated May 3, 2025. These terms govern all In Sight Publishing content—past, present, and future—and supersede any prior notices. In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons BY‑NC‑ND 4.0; © In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen 2012–Present. All trademarks, performances, databases & branding are owned by their rights holders; no use without permission. Unauthorized copying, modification, framing or public communication is prohibited. External links are not endorsed. Cookies & tracking require consent, and data processing complies with PIPEDA & GDPR; no data from children < 13 (COPPA). Content meets WCAG 2.1 AA under the Accessible Canada Act & is preserved in open archival formats with backups. Excerpts & links require full credit & hyperlink; limited quoting under fair-dealing & fair-use. All content is informational; no liability for errors or omissions: Feedback welcome, and verified errors corrected promptly. For permissions or DMCA notices, email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com. Site use is governed by BC laws; content is “as‑is,” liability limited, users indemnify us; moral, performers’ & database sui generis rights reserved.

#CulturalResistance #EarlyEmpowerment #genderParity #PoliticalWill #WomenSLeadership

Unblinking

Unbeirrter Blick. Drei Hände rahmen ein Gesicht – zwischen Schutz und Ausgesetztsein.

Unblinking (2025) – ein Porträt in Öl, das nicht wegsehen will: Zivilcourage, Wachsamkeit, Verantwortung.

Aus der Serie Generation Courage.

📷 Mehr dazu: https://www.corneliaessaid.de/project/unblinking-2025/

#ZeitgenössischeKunst #OilPainting #Porträt #Zivilcourage #Kunst #ContemporaryArt #GenerationCourage #BerlinArt #Malerei #FineArt #ArtCollectors #VisualArt #CulturalResistance #ArtForChange

Inaugural Chicano Hollywood Film Festival launches July 17-20 in Pomona, showcasing 90+ films celebrating Chicano storytelling, resistance, and cultural identity. A powerful platform for underrepresented voices in entertainment. #ChicanoFilm #CulturalResistance

Looking for inspiration, bold visuals, and cultural resistance all in one place?

Pop Brasil: Vanguard and New Figuration, 1960–70 at @pinacotecasp is not your typical Pop Art show. It’s a politically charged, interactive, and deeply Brazilian reimagining of pop culture through the lens of dictatorship, media, gender, and mass consumption.

Our latest blog takes you behind the scenes of the exhibition—unpacking iconic works, radical ideas, and why this moment in art still matters today.

🎨 Read the blog

🕶️ Visit the show

💥 Discover how pop became protest in Brazil.

https://open.substack.com/pub/cybersynthcircular/p/pop-brasil-brazilian-pop-art-as-resistance?r=288ilo&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

#PopBrasil #PinacotecaSP #BrazilianArt #ContemporaryArt #HelioOiticica #CulturalResistance #ArtAsActivism #SãoPauloEvents #PopArtRevolution #BrazilianPopArt #Pop #Brasil #exhibition #Pinacoteca #SãoPaulo #HélioOiticica #NelsonLeirner #WandaPimentel #PoliticalArtBrazil #art #dictatorship #SãoPauloArtExhibitions2025 #Brazilian #ContemporaryArt #CulturalResistance #May1968Brazil #ParangolésOiticica

🔴 JOIN US TODAY!

Shadows of Illiberalism continues in Berlin with:

🧠 Bifo on Exhaustion & Hyper-Colonialism

🎨 Panel on art & activism in HU, PL & SK

🎟️ disruptionlab.org/shadows-of-illiberalism

#DNL35 #CulturalResistance #Berlin

🔴 Shadows of Illiberalism brings together artists, researchers & activists to confront the rise of the radical right in Europe — from culture wars to AI propaganda. JOIN US!

🗓️ June 13–15 · Berlin

🎟️ disruptionlab.org/shadows-of-illiberalism

Una riflessione sul populismo becero e l'ignoranza cieca.

“Resistenza culturale contro il populismo e la deriva autoritaria”

Grazie 🦔

🌹

A reflection on crude populism and blind ignorance.

“Cultural resistance against populism and authoritarian drift”

Thank you 🦔

#resistenzaculturale #populismo #autoritarismo #ignoranza #libertàdipensiero

#culturalresistance #populism #authoritarianism #ignorance

“Resistenza culturale contro il populismo e la deriva autoritaria”

Link nei commenti.

Grazie 🦔

🌹

A reflection on crude populism and blind ignorance.

“Cultural resistance against populism and authoritarian drift”

Link in comments.

Thank you 🦔

#resistenzaculturale #populismo #autoritarismo #ignoranza #libertàdipensiero

#culturalresistance #populism #authoritarianism #ignorance