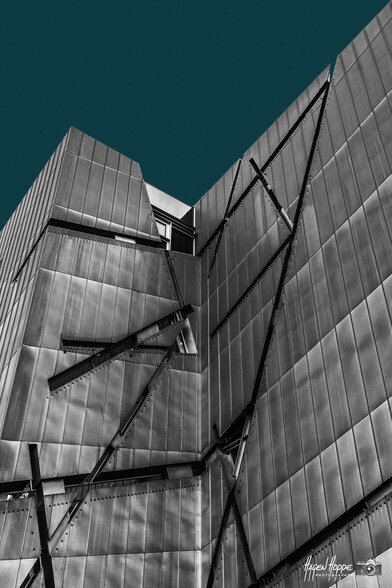

#Osnabrück #Nussbaumhaus im Regen. #Museum #Fotografie #Architektur #Daniellibeskind #Felixnussbaum #Kunst #Erinnerung #NSOpfer #Bildersammlung #Schwarzweiß #Monochrom #Leica #Lowkey #Nachtfotografie #Regennacht

#daniellibeskind

🧵 3/3

Kudos to "The Brutalist" director for tackling a number of big themes in the film, a central one being the relationship of art to capitalism.

Yet many of the lines about beauty and ugliness given to Brody struck a false note. Although he was supposed to have come from the Bauhaus with reputation inn Europe as an important modernist architect, much of his rhetoric in the film about architectural beauty and its value struck me as drawing on an older, premodernist tradition of humanism.

In fact, the relation of Bauhaus immigrants to corporate USA is more complex than that suggested by the film, as a study of the career of Mies van der Rohe or a reading of James Sloan Allen's "The Romance of Commerce and Culture" might suggest.

However, I should point out that the linked article shows that at least one architect considers the film an outstanding exploration of the tension between power and design.

#TheBrutalist #Bauhaus #Modernism #Architecture #DanielLibeskind

https://forward.com/culture/film-tv/683740/the-brutalist-film-architecture-israel/

Autlook Boards IDFA Forum’s ‘Architecture as Invention’ on Gound Zero Master Planner Daniel Libeskind (EXCLUSIVE)

#Variety #Global #News #Autlook #DanielLibeskind #DocumentariestoWatch #Idfa #MichaelMadsen

#HolocaustMemorialTower in het Joods Museum in Berlijn door #DanielLibeskind

Jüdisches Museum . Berlin . Daniel Libeskind . 1999

.....

#Berlin #Architektur #architecture #photographyisart #photography #modernearchitektur #modernarchitecture #photo #daniellibeskind #jüdischesmuseum #Fotografie #Deutschland #Fotobubble #Photocommunity

Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum is a "foreboding experience"

Continuing our series on deconstructivism we look at the Jewish Museum in Berlin, one of the architect Daniel Libeskind's first completed projects.

The zigzagging, titanium-zinc-clad building was the winner of an anonymous competition held in 1988 for an extension to the original Jewish Museum, which had occupied an 18th-century courthouse since 1933.

Daniel Libeskind designed a zigzagging extension to Berlin's Jewish Museum. Photo by Guenter Schneider

Libeskind responded to the competition with a highly experiential and narrative-driven design called "Between the Lines", with a distinctive form sometimes described as a "broken Star of David",

Inside, sharp forms, angular walls and unusual openings to create disconcerting spaces informed by the "erasure and void" of Jewish life in Berlin after the Holocaust.

It is clad in titanium-zinc panels

"It's an experience, and some of it is foreboding," said Libeskind,

"Some of it is inspiring, some of it is full of light. Some of it is dark, some of it is disorienting, some of it is orienting," he continued.

"That was my intent in creating a building that tells a story, not just an abstract set of walls and windows."

The extension stands alongside the original museum

The extension stands apart from the historic museum and has no entrances or exits of its own, accessible only via an underground passageway, "because Jewish history is hidden," explained Libeskind.

"I sought to construct the idea that this museum is not just a physical piece of real estate. It's not just what you see with your eyes now, but what was there before, what is below the ground and the voids that are left behind," he continued.

[

Read:

Daniel Libeskind is deconstructivism's "late bloomer"

](https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/19/daniel-libeskind-profile-deconstructivism/)

The idea of movement – a key concept of deconstructivism – informs three axes that cut across the zigzag plan and organise movement through the building: the Axis of Continuity, Axis of Exile and the Axis of the Holocaust.

The Axis of Continuity begins with the steps down from the original museum and leads up a long, high staircase that provides access to the permanent exhibition spaces on the upper storeys and ends in a blank white wall.

Three axis cut through the building

The exhibition rooms have, since 2020, contained the exhibition "Jewish Life in Germany Past and Present", telling the story of Jews in Germany from their beginnings to the present day.

A staircase with thin, diagonal windows provides visitors with glimpses outside as they ascend to the buildings upper level

Externally, these windows cut across floor levels to create an abstract pattern - based on the addresses of notable Berlin figures – that makes it impossible to determine where one floor ends and another begins.

The staircase is lit with thin diagonal windows

The Axis of Exile is dedicated to the lives of Jews forced to leave Germany, and leads to the Garden of Exile, where a series of 49 tall, tilted concrete boxes are topped with plants. 48 contain soil from Berlin and one soil from Jerusalem.

The Axis of the Holocaust contains displays of objects left by those killed by the Nazis, and leads to a separate, stand-alone concrete building called the "voided void" or Holocaust Tower.

The Garden of Exile contains 49 tall concrete boxes

Only accessible through the museum's underground passageways and described as an "unheated concrete silo", this exposed concrete space is illuminated through a narrow slit in its roof.

"It's important not to repress the trauma, it's important to express it and sometimes the building is not something comforting," said Libeskind about the building in a 2015 interview with Dezeen.

Several concrete voids cut through the building

"Why should it be comforting? You know, we shouldn't be comfortable in this world. I mean seeing what's going around," he added.

Where the three axes meet is the Rafael Roth Gallery, an installation space that hosts changing installations.

One void contains an artwork made from 10,000 iron faces

Cutting directly through the centre of the building is a strip of five exposed concrete voids that "embody absence", only some of which can be entered.

"It is a straight line whose impenetrability becomes the central focus around which exhibitions are organised," said the practice.

"In order to move from one side of the museum to the other, visitors must cross one of the bridges that open onto this void," it continued.

[

Read:

Deconstructivist architecture "challenges the very values of harmony, unity and stability"

](https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/03/deconstructivist-architecture-introduction/)

These spaces, which are unheated and only illuminated by natural light, are designed to interrupt the flow of movement through the building, representing what Libeskind describes as "that which can never be exhibited when it comes to Jewish Berlin history: humanity reduced to ashes."

One of these voids contains an artwork called "Shalekhet (Fallen Leaves)" by the artist Menashe Kadishman, comprised of more than 10,000 faces made from iron plates that cover the floor.

The Jewish Museum was one of Libeskind's first built works

Minimal, grey and white finishes have been used in the interiors, with areas of built-in lighting highlighting the axial routes through the museum.

More recently, Libeskind has returned to the site to design two extensions – a steel and glass covering for the courtyard of the historic courthouse, and the nearby W. Michael Blumenthal Academy.

Libeskind's work at the Jewish Museum led to commissions for several memorials and museums over the rest of his career, including the Dutch Holocaust Memorial of Names in Amsterdam and the masterplan for the Ground Zero site following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The photography is byHufton+Crow.

Illustration is by Jack Bedford

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements.Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Eisenman, Gehry, Hadid, Koolhaas, Libeskind, Tschumi and Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›

The post Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum is a "foreboding experience" appeared first on Dezeen.

#deconstructivism #all #architecture #cultural #germany #daniellibeskind #berlin #museums

Daniel Libeskind is deconstructivism's "late bloomer"

We continue our deconstructivist architecture series with a profile of Daniel Libeskind who designed one of the movement's most evocative buildings, the Jewish Museum Berlin.

"You know, we shouldn't be comfortable in this world," Polish-American architect Libeskind once told an audience at an event at the Roca London Gallery.

"I'm always surprised that people think that architecture should be comforting, should be nice, should appeal to your domesticity," he said. "Why should [architecture] be comforting?"

Top: Daniel Libeskind. Illustration by Vesa S. Above: He is a key proponent of deconstructivism. Photo is by Stefan Ruiz

Libeskind was referring to his design of the Jewish Museum Berlin, a controversial building that led the now-76-year-old architect to achieve international fame.

The museum perfectly encapsulates what has become known as his trademark style – an incessant use of sharp angles, slanted surfaces and fragmentation that aims to be symbolic, emotional, and sometimes even uncomfortable.

While designing the museum, the architect came up against criticism because his design did not resemble traditional museums and instead "challenges every facet of convention".

It is, therefore, no surprise that his work is synonymous with deconstructivism – the influential architecture movement from the 1980s that opposed rationality and symmetry.

He is the architect behind the Jewish Museum Berlin. Photo is by Guenter Schneider

Libeskind, the son of Jewish Holocaust survivors, was born in 1946 in Lód'z, Poland. Today he is one of the world's most renowned architects.

Yet, despite his starchitect status, architecture was not always his focus. In fact, the self-professed "late bloomer" did not complete a building until the age of 52.

As a child, Libeskind's first passion was music. He trained as an accordion player and, after migrating to Israel with his family in 1957, received a scholarship from the American-Israel Cultural Foundation that led him to perform as a virtuoso.

[

Read:

Deconstructivist architecture "challenges the very values of harmony, unity and stability"

](https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/03/deconstructivist-architecture-introduction/)

It was not until his family migrated to New York in 1965 that he set his sights on architecture. Though, his musical background continues to influence his work.

"I've always thought that architecture and music are closely related," he explained in his TED talk.

"First of all emotionally architecture is as complex and as abstract as music but it communicates to the soul, it doesn't just communicate to the mind."

Libeskind exhibited City Edge at the MoMA's Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition

Libeskind began his architectural career studying at Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and later at the School of Comparative Studies at Essex University. After working briefly for both Richard Meier and fellow deconstructivist architect Peter Eisenman, he went on to work in architectural academia.

His work was catapulted into the spotlight in 1988 when curator Philip Johnson invited him to take part in the seminal Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York – despite not having completed a building at the time.

The exhibition, which also featured works by his fellow deconstructivists Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Bernard Tschumi, Eisenman and Wolf Prix, saw Libeskind present an unbuilt proposal for a housing development named Berlin City Edge.

However, in a recent exclusive interview with Dezeen, Libeskind shrugged off his deconstructivist label, claiming that today "the style doesn't mean very much to [him]".

Libeskind was invited to take part in the exhibition by Philip Johnson

The term deconstructivism derives from the deconstruction approach to philosophy and the Russian architectural style of constructivism. According to Libeskind, it "was not a great word for architecture".

"I don't find usefulness in this term in architecture, I always felt slightly repulsed by it because it became a kind of intellectual trend," Libeskind told Dezeen.

Instead, he said, the exhibition marked a change in the industry and an emergence of architects who wanted to reestablish architecture as a form of art.

[

Read:

"I always felt slightly repulsed" by deconstructivist label says Daniel Libeskind

](https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/06/deconstructivism-interview-daniel-libeskind/)

"[Deconstructivism is] not a style at all, but something in the air about the demise of former logic and former notions of harmony and former notions of beauty."

"These architects had a very different idea than the sort of corporate and conventional styles of the late 1980s," he reflected, referring to the other MoMA exhibitors.

A year after the seminal MoMA exhibition, Libeskind won the commission for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, which would be his second completed building following the Felix Nussbaum Haus museum in Germany and marked the beginning of his illustrious career in built works.

Libeskind was the masterplanner of Ground Zero in New York. Photo is by Hufton+Crow

To complete the project, he moved to Berlin and established Studio Libeskind with his wife Nina, which he continues to direct today. The museum officially opened in 2001 and soon became an established landmark in the capital.

Formed of a sharp zigzagging plan broken up by deep voids, the museum is designed to trigger "memories and emotional responses".

"When I explored the site for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, I put myself into the souls of those who are not there, into the emptiness I felt," Daniel Libeskind once wrote for CNN.

"I tried to see how it would feel to be there when you're not there. What does it mean to create a space for those who were murdered, who disappeared in the smoke?"

His first building was the Felix Nussbaum Haus museum. Photo is by Studio Libeskind

Shortly after the completion of Jewish Museum Berlin, Libeskind won the high-profile commission for Ground Zero, the masterplan for the rebuilding of New York's World Trade Center following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

His framework for Ground Zero included a memorial and a museum to the tragedy, alongside a transport hub and cluster of towers.

There was also a central skyscraper called the Freedom Tower, which had a symbolic height of 1,776 feet to represent the year of America's independence, though this was replaced by the One World Trade Center by SOM.

It was a turbulent process and experienced a number of hold-ups, but it cemented him as the go-to architect for creating poignant monuments for tragic events, defining his work that followed.

[

Read:

Frank Gehry brought global attention to deconstructivism

](https://www.dezeen.com/2022/05/17/frank-gehry-brought-global-attention-to-deconstructivism/)

Among Libeskind's other key projects is the aluminium Imperial War Museum North in the UK, the parasitic Military History Museum in Dresden and the titanium-clad Denver Art Museum in the US.

He is also the architect behind the angular Reflections at Keppel Bay towers in Singapore and the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre in Ireland – all of which are characterised by Libeskind's signature splintered forms.

The Military History Museum in Dresden is another key project by Libeskind. Photo is by Hufton+Crow

Libeskind has come under much criticism for his work and trademark style, which architectural historian William J R Curtis once described as "a reduction to caricature of all that the Jewish Museum set out to achieve".

More recently, novelist Will Self claimed Libeskind put money before art in a piece for British architecture magazine BD attacking high profile architects.

However, Libeskind never reads his critics and has previously said that he does not try to be liked.

"When things are first shown they are difficult," Libeskind told Dezeen. "If you read the reviews of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, it was a failure, a horrible piece of music."

"You have to give it time. Architecture is not just for the moment, it is not just for the next fashion magazine. It's for the twenty, thirty, fifty, one hundred, two hundred years if it's good; that's sustainability."

In Denver he designed the titanium-clad Denver Art Museum. Photo is by Alex Fradkin

Though Libeskind does not see himself as a deconstructivist, he understands why his work is associated with the movement.

This is because, he said, his goal is to "not to let architecture freeze itself and fall asleep, not to let architecture become just a kind of business proposition, just to build something".

"Maybe that is what deconstructivism is, really is," he told Dezeen.

"It's architecture that seeks meaning. Which is, I think, what brings us close to the philosophical sense of deconstruction in philosophy or literature that seeks to uncover what is there, but it's not readily accessible by the blinkers of anywhere on our eyes."

The illustration is by Jack Bedford

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Eisenman, Gehry, Hadid, Koolhaas, Libeskind, Tschumi and Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›

The post Daniel Libeskind is deconstructivism's "late bloomer" appeared first on Dezeen.

#deconstructivism #all #architecture #daniellibeskind #profiles

Seven early deconstructivist buildings from MoMA's seminal exhibition

Continuing our deconstructivist series, we look at seven early buildings featured in the seminal 1988 Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition at the MoMA that launched the careers of Zaha Hadid and Daniel Libeskind.

Curated by Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Philip Johnson and architect and academic Mark Wigley, the exhibition – named simply Deconstructivist Architecture – featured the work of seven emerging architects: Hadid, Frank Gehry, Wolf Prix, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman, Libeskind and Bernard Tschumi.

"Deconstructivist architecture focuses on seven international architects whose recent work marks the emergence of a new sensibility in architecture," explained MoMA in a press release announcing the exhibition.

"Obsessed with diagonals, arcs, and warped planes, they intentionally violate the cubes and right angles of modernism."

Termed deconstructivists – a combination of the philosophical theory of deconstruction and the 1920s constructivist architecture style – the architects all shared a methodology and aesthetic that drew from both sources, according to Johnson and Wigley.

"Their projects continue the experimentation with structure initiated by the Russian Constructivists, but the goal of perfection of the 1920s is subverted," continued MoMA.

"The traditional virtues of harmony, unity, and clarity are displaced by disharmony, fracturing, and mystery."

Read on for seven projects featured in the seminal Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition:

Zaha Hadid: The Peak, Hong Kong

The Peak was Hadid's winning entry into a high-profile architectural competition in 1983 to design a private club perched in the hills above Hong Kong.

Described in the exhibition publication as a "horizontal skyscraper", the club would have been constructed from shard-like fragments within an artificial cliffscape carved into the rock.

Although never built, the competition and the constructivist-informed paintings depicting it launched Hadid's career.

Bernard Tschumi: Parc de la Villette, France

Parc de la Villette was one of the 1980s' defining deconstructivist projects. Tschumi was chosen as the competition winner to design a major park in Paris ahead of 470 international entries, including fellow exhibitors Koolhaas, Hadid, and Eisenman who entered with deconstructionism theorist Jacques Derrida.

Tschumi arranged the park around three separate ordering systems – points, lines and surfaces – with numerous abstracted red follies distributed on a grid across the landscape.

According to Tschumi "it is one building, but broken down in many fragments".

Model photo is by Gerald Zugmann

Wolf Prix/Coop Himmelb(l)au: Rooftop Remodeling Falkestrasse

Described in the MoMA exhibition material as a "skeletal winged organism", this rooftop extension to a law firm in Vienna was completed by Prix's studio Coop Himmelb(l)au in the year that the exhibition opened.

A large meeting room is enclosed in an angular steel and glass structure that is in stark contrast to the traditional roofscape.

Rem Koolhaas: Boompjes tower slab, the Netherlands

The Boompjes tower slab was the result of a commission in 1980 from the city of Rotterdam to investigate the future of high-rise buildings in the city.

Planned for a narrow plot of land alongside a canal, the Boompjes tower slab would have been an apartment block with communal facilities including a school at its base and a "street in the sky" at its top.

Its form merged the appearance of a single slab and a series of individual towers.

Peter Eisenman: Biology Center for the University of Frankfurt, Germany

Designed as a biotechnological research centre at the University of Frankfurt, this building derives its form from an investigation of DNA.

The unrealised project consists of a series of blocks informed by the geometric shapes used by biologists to depict DNA code. The blocks would have been arranged alongside each other and each broken into two parts. Additional lower rise blocks intersect the regularly aligned forms.

It is described by the exhibition curators as "a complex dialogue between the basic form and its distortions".

Daniel Libeskind: City Edge Competition, Germany

City Edge was a 450-metre-long building proposed as part of the redevelopment of the Tiergarten area of Berlin by Libeskind, who had not completed a building at the time of the exhibition.

The residential and office block would have risen from the ground so that its end was raised 10 storeys above the Berlin wall.

It acts both as a wall dividing the city and also shelters a public street to connect it. "It is subverting the logic of a wall," said the exhibition curators.

Photo is by IK's World Trip

Frank Gehry: Gehry House, USA

One of two projects designed by Gehry to be included in the exhibition, this house was designed in three stages between 1978 and 1988.

The dramatic revamp of the architect's own home wraps the original house in a series of geometric forms that seem to burst from its structure.

"The force of the house comes from the sense that these additions were not imported to the site but emerged from the inside of the house," said the exhibition curators. "It is like the house had always harbored these twisted shapes within it."

Illustration is by Jack Bedford

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Eisenman, Gehry, Hadid, Koolhaas, Libeskind, Tschumi and Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›

The post Seven early deconstructivist buildings from MoMA's seminal exhibition appeared first on Dezeen.

#deconstructivism #all #architecture #zahahadidarchitects #daniellibeskind #moma #roundups

"I always felt slightly repulsed" by deconstructivist label says Daniel Libeskind

Alt headline: Deconstructivism "not a style at all" says Daniel Libeskind

Deconstructivism was not a suitable name for the architecture that it represented argues architect Daniel Libeskind in this exclusive interview as part of our series exploring the 20th-century style.

Polish-American architect Libeskind, who is considered a key proponent of deconstructivism, told Dezeen that the movement's name is better suited as a term for philosophy.

"The style doesn't mean very much to me," reflected Libeskind. "[Deconstructivism] was not a great word for architecture," he explained.

"I don't find usefulness in this term in architecture, I always felt slightly repulsed by it because it became a kind of intellectual trend."

"It has very little to do with how I view architecture"

Deconstructivism is a term that was popularised by an international exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1988. It derives the deconstruction approach to philosophy and the architectural style of constructivism.

While being too philosophical for architecture, Libeskind also believes that the name has negative connotations, prompting thoughts of buildings "falling apart".

Photo is by Bitter Bredt

"I personally have always felt that [deconstructivism] was not a good term for architecture, because deconstruction in architecture seems to suggest falling apart," he said.

"It has very little to do with how I view architecture, which is really an art that has a grand history, that is social in its character, that is cultural and that has a huge longevity to it."

Deconstructivism is "not a style at all"

Though Libeskind does not have an affinity with deconstructivism today, he was one of seven renowned architects who took part in the seminal MoMA show. The others were Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenmann, Bernard Tschumi and Wolf Prix.

At the time, he had never completed a building and instead presented a conceptual project called City Edge, which imagined the renewal of the Tiergarten district in west Berlin.

To Libeskind, the exhibition did not represent the emergence of an architectural style, but rather a turning point within the industry, just as it was "running out of ideas".

"[Deconstructivism is] not a style at all, but something in the air about the demise of former logic and former notions of harmony and former notions of beauty," Libeskind said.

"These architects had a very different idea than the sort of corporate and conventional styles of the late 80s," he added, referring to his fellow MoMA exhibitors.

X. Image is courtesy of Studio Libeskind

Libeskind explained that buildings of this era are all underpinned by an ambition to tear up the rule book and reestablish architecture as a form of art.

"It was the moment when architecture was again an art, when people realised that all these restrictions on architecture are really political and social and have little to do with the art of architecture," he said.

"It's no longer just something taken out of a catalogue of existing typology in a historical way."

Era of deconstructivism is not over

According to Libeskind, the MoMA exhibition show marked "a very important moment" in architectural history.

This is because its influence on architects continues to be evident today, and the era of architecture it represented is not over, he said.

"It wasn't a matter even of style, or a matter of the name, it was just something that has suddenly exploded into the world," explained Libeskind.

"In that sense, I think it was a very important moment of time, and we are still part of it."

[Add intro as related post]

"I think every student of architecture who goes to school today would not be doing what she or he is doing, without having a sense that something has happened to architecture that will never go back again," Libeskind concluded.

"That's thanks to this exhibition and this group of really brilliant architects."

Read on for the edited transcript of the interview with Libeskind:

[Add transcript once edited]

Deconstructivism is of one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Bernard Tschumi and Wolf Prix. Read our deconstructivism series ›

The portrait of Libeskind is byStefan Ruiz.

The post "I always felt slightly repulsed" by deconstructivist label says Daniel Libeskind appeared first on Dezeen.

#deconstructivism #all #architecture #news #interviews #daniellibeskind

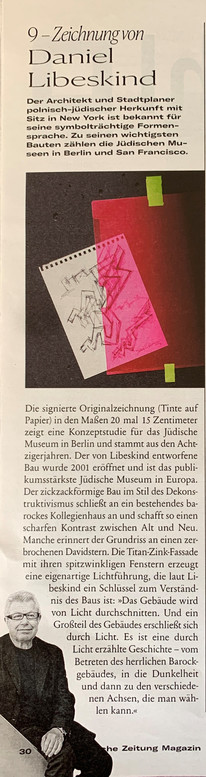

Ein #Unikat bei dem Magazin der @sueddeutsche_feed@botsin.space gewinnen und Gutes tun - zB. eine Konzeptstudie zum #JüdischesMuseumBerlin von #DanielLIBESKIND. Wie? ganz einfach: zB mit einer Spende an die #UNOFLÜCHTLINGSHILFE - https://bit.ly/3EAcrLP

Daniel Libeskind creates angular cognac bottle to "embody the legacy of Richard Hennessy"

Architect Daniel Libeskind has created an angular bottle for the Richard Hennessy cognac, which is named after the founder of drinks brand Hennessy.

The Baccarat crystal bottle has an angular external shape surrounding a curved internal form reminiscent of a traditional cognac bottle. The design was created to evoke a sense of history and the future.

Daniel Libeskind designed an angular bottle for Hennessy

"I am inspired by the interplay of history and the future – a particular magic happens when the two come together," said Libeskind.

"The inspiration for the decanter came from the powerful emblem of Richard Hennessy and symbol of the future of the brand," he continued. "I wanted to honour the history while elevating it."

Its inner form is the shape of a traditional cognac bottle

By combining the curved and angled forms Libeskind aimed to express the tradition of Hennessy, which was founded by Richard Hennessy in 1765, and give "a new energy and complexity to the liquid inside" the bottle.

"I started with the classic Hennessy bottle shape, but I wanted to push the boundary of the design," he explained. "We also wanted to create something strong to embody the legacy of Richard Hennessy."

[

Read:

Frank Gehry forges crinkled gold bottle to mark 150th anniversary of Hennessy X.O

](https://www.dezeen.com/2020/09/25/hennessy-x-o-150th-anniversary-frank-gehry-bottle/)

"The result was to insert the soft curved shape within the crystalline form that echoes the spirit of Richard Hennessy," he continued.

"The juxtaposition of the organic curves with the bold geometric form of the silhouette gives a new energy and complexity to the liquid inside."

Libeskind designed the bottle to represent the brand's tradition and future

Libeskind is one of the world's best-known architects and has designed buildings all over the world, including the Jewish Museum Berlin and the masterplan for New York's World Trade Center site.

He likened the process of designing the bottle to that of designing a building.

The bottle was made from Baccarat crystal

"The design process began several years ago with the common goal of creating something spectacular and rare," he continues.

"It's quite organic, but it always starts with a spark of inspiration—an idea or a place or even a sense—and then expands into a flame of possibilities! The decanter was developed over many years — like a major city plan or cathedral.

Libeskind is the latest architect to design a bottle for Hennessy. Recently, Pritzker Prize-winning architect Frank Gehry created a limited-edition bottle for the 150th anniversary of Hennessy's X.O cognac.

The post Daniel Libeskind creates angular cognac bottle to "embody the legacy of Richard Hennessy" appeared first on Dezeen.

Jüdisches Museum ehrt Knobloch und Libeskind | DW | 12.11.2021

#CharlotteKnobloch #DanielLibeskind #JüdischesMuseumBerlin #Judentum #Auszeichnung #JLID1700

Daniel Libeskind: Amsterdamer Holocaust-Denkmal eingeweiht | DW | 19.09.2021

#DanielLibeskind #Holocaust #Mahnmal #Amsterdam #Shoa #NS-Opfer #Nationalsozialismus #Hitler

Daniel Libeskind: Amsterdamer Holocaust-Denkmal öffnet | DW | 19.09.2021

#DanielLibeskind #Holocaust #Mahnmal #Amsterdam #Shoa #NS-Opfer #Nationalsozialismus #Hitler

"Everything changed in architecture" after 9/11 attacks says Daniel Libeskind

The terrorist attacks on New York's World Trade Center helped the public understand the importance of architecture, says the architect who masterplanned the rebuilding at Ground Zero as part of our 9/11 anniversary series.

Speaking to Dezeen in an exclusive interview, Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind said that "everything changed in architecture" after the tragedy.

Prior to the attacks, he said, urban planning was largely done without public input. However, the attack on the Twin Towers revealed that big architectural projects "belong to citizens".

The Ground Zero site (above) was masterplanned by Daniel Libeskind (top). This photo is by Hufton + Crow

"I think that the impact [of 9/11] was on the whole world," he told Dezeen. "Everything changed in architecture after that. People were no longer willing to do it as before."

"It had an impact in the sense that people understood that big projects are not only for private development, they belong to citizens," he explained. "I think it gave people a sense that architecture is important."

On 11 September 2001, Al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four commercial aircraft. Two were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, claiming 2,753 lives.

Another plane hit the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, while the fourth crashed into a field in Pennsylvania. The overall death toll of the four coordinated attacks was 2,996.

One World Trade Center by SOM was erected as part of the rebuilding. The photo is by Hufton + Crow

Two years after the attack, Libeskind won a competition to masterplan the 16-acre World Trade Center site.

His framework included a memorial and a museum to the tragedy, a transport hub plus a cluster of towers including a central "Freedom Tower" with the symbolic height of 1,776 feet, representing the year of America's independence.

However, Libeskind's Freedom Tower design was never built and instead One World Trade Center by SOM rose in its place.

Public participation became "much more important"

Libeskind attributes the fact that there was a design competition at all to public demand.

"There was no original competition at all for Ground Zero," he explained. "It was a port authority call for good ideas that they could use," he said, referring to the body that owns the World Trade Center site.

"It was the public that demanded what they saw, and luckily, [my idea] was the one that was in the eye of the public," he continued.

"The public said 'we want this project'...so the port authority was, in a way, forced by the public to implement something that originally was not part of their agenda."

Libeskind's original masterplan created a semi-circle of towers around a memorial

Libeskind said that this "showed the power of the public in determining the future of their cities".

"Planning is not a private business," he added. "It should be determined by a democratic voice of all the different interests, which includes developers and agents, the people, you know, all sorts of different constituencies."

"New York is about tall buildings"

Following the attacks, Libeskind said that some people thought that tall buildings would no longer be built in the city and that Lower Manhattan would fall into a state of decline.

"The mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, just wanted low buildings," recalled Libeskind.

"People said nobody will ever come back to downtown, companies will move to New Jersey, they'll move to Connecticut," he continued. "People don't want to be there anymore."

However, Libeskind felt differently, saying that "New York is about tall buildings" and "always has been".

He compared the aftermath of 9/11 to the coronavirus pandemic, which some people predict will lead to the demise of dense cities and office working.

"Today with a pandemic, people say the same thing," Libeskind said. "People will not work with offices anymore." But he believes that "people will always come" back to cities.

Site "belongs to all of us"

Reflecting on his work on the Ground Zero masterplan, Libeskind likened its challenges to designing a whole American city.

While reintroducing office skyscrapers and adding valuable real estate to the site, he decided to dedicate half of the land to public space to create a neighbourhood accessible to everyone, rather than to just office workers.

"My main goal in the masterplan was, first of all, to create a civic space, not to just be concerned with private investment, but to create a significant memorial, which brings people going to the site in an open social way," he said.

"This was a commercial site where every square inch is worth a lot of money," he explained. "But I felt that somehow it's not a piece of real estate anymore."

"It's something that belongs to all of us," he said.

A visual of 5 World Trade Center at Ground Zero, courtesy of KPF

The Ground Zero masterplan is yet to reach completion, with KPF's 5 World Trade Center next in line to break ground. However, Libeskind believes it has already achieved his aims.

Recalling the day that Ground Zero reopened to families of victims, he said: "I still remember the words people said to me: 'Thank you, you delivered what you promised'".

"After 20 years, it's not finished," he continued. "But it's pretty much what was intended to be and how lucky to have been part of this process."

Read on for an edited transcript of the interview.

Lizzie Crook: Could you reflect on your experience of working on the Ground Zero masterplan and tell me a little bit about how you approached the project?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, it was a very intense process, you know, which had so many participants. The city, the agency, the developers, the general public. It was an all-consuming process. And the only way one could do it was through a democratic process. It was not always difficult, it wasn't always easy.

It had its ups and downs, but it was always meaningful, and always... I had to be really passionate to stick to it, because the challenges were immense. Challenges were complex. So what can I say? Humbled to think of the scale of the project, but it was to pursue the work and try to work in the spirit of openness and that's what I did.

Lizzie Crook: So what were your main goals for the masterplan?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, my main goal in the masterplan was, first of all, to create a civic space, not to just be concerned with private investment, but to create a significant memorial, which brings people going to the site in an open social way. And to create as much public space as possible, which would then permit people to see the memorial as something that is crucial to the memory of the city.

But also to balance the needs of the development of over 10 million square feet of office density, with culture, and with pedestrian pleasures, and to balance memory, and the future in a very unique way.

So that was really the goal. And of course, to meet that incredible programme, which is almost like building a downtown or a whole American city, within 16 acres. But remember that, out of that 16-acre site, there are eight acres of public space, which is what my goal was. To create that sense that this is for New York, this is for people, and not only for people lucky enough to work with those offices.

Lizzie Crook: How did you prevent the site from becoming a sad space and instead make a vibrant neighbourhood?

Daniel Libeskind: It's a balance. You don't want to make New York into a sad city. You don't want to create something that is just mostly shadows and darkness. What you want to do is to create a public and social space, which speaks about the event but in a positive way.

And of course, to do that I went all the way down to the bedrock, the slurry wall, which supports the site and created a sense that this is not a two-dimensional space, that this is really a fully three-dimensional space where you can reach the place of tragedy, but also the place where you can see the rising of the foundations of New York, which still really support that site with the slurry wall.

And of course, to balance the streets, the big buildings that have hundreds of thousands of people working. There is no retail fronting the memorial. You have more quiet streets. And then of course on the other side, you have the noisy shopping streets of New York. So again on many different levels to create a composition, which stays true to what the spirit of New York is, which is a spirit of resilience, and the spirit of joy. That is, we are now in different life of this really spectacular new developmental memorial site.

Lizzie Crook: Do you think the Ground Zero masterplan has achieved its aims?

Daniel Libeskind: It definitely has achieved its aims because life has returned. After six o'clock, Wall Street was just a dark area, there was no retail there, no people living there. It was dead at night. The plaza of the Twin Towers was closed because it was too windy to walk through it.

So I created a sense of a neighbourhood by creating this composition of buildings, which are also symbolic elements, you know, the 1776-feet-tall tower number one, the fact that the buildings stood in a sort of stood in a spiral movement within the grid of New York that echos the torch of Liberty.

The fact that I brought water to the site, you know, the waterfalls, in order to really bring nature in to screen the busy streets and noise of downtown New York. Of course, exposing the slurry wall, which is no small achievement, to make people understand where they are, that this is the bedrock, this is where we are stood and where it stands still. Those are all the kind of elements.

The only anecdote that I can tell you is that when I came to the site, with all the finalist architects, many great architects, and we were on top of one of the skyscrapers next door, and somebody said, does anybody want to go to the site? I said, yes. I was the only one because we could see the site much better from a high rise office building. But I walked down there with my partner and wife Nina.

And really, my life changed as I walked down that route, 75 feet below the streets of New York. And when I touched the slurry wall, I realised really what the site was about, it wasn't about just nice buildings and traffic and all those important planning ideas, it was about deep memory.

I actually called my office, which was still in Berlin at the time, and I said, forget everything we've done, just put it in the garbage. Already a lot of models, drawings, simulations, and animations, you know, working with many experts on this project, I said, forget it.

Throw it out. It's not about that. It's about not building where the Twin Towers stood. Making it all really part of the public space of New York. And I'm really impressed how in a democratic process, this came to fruition. You know, nobody declared the site a sacred site. This was a commercial site where every square inch is worth a lot of money. But I felt that somehow it's not a piece of real estate anymore.

It's something that belongs to all of us. I was to work in a democracy, as fraught as it was, it was very fraught with many battles to fight, but I am really a great advocate and believer in democracy. I don't buy projects that are just from the top down but involve all sorts of interests. And I think it just shows that democracy does work.

Lizzie Crook: Reflecting on the event of 9/11 itself, how would you describe its impact on architecture in the US?

Daniel Libeskind: It had a huge impact in many ways. Number one, it had an impact in the sense that people understood that big projects are not only for private development, they belong to citizens. You know, I don't know what you know, the story, but the original, there was no original competition at all for Ground Zero.

It was a port authority call for good ideas that they could use, right. But it was the public that demanded what they saw, and luckily [my idea] was the one that was in the eye of the public. The public said 'we want this project' that's what we want. We don't want a typical port authority collage of ideas.

We want a project that has all these elements, symbolic elements, the great social public space, the grand memorial, the underground and so on. And so the port authority was, in a way, forced by the public to implement something that originally was not part of their agenda. So first of all, the competition showed the power of the public in determining the future of their cities. It also meant that subsequently, people in New York, were far more sensitive to what they could build, and how high should it be, and how can it respond to the context where people are living. So public participation became, I think, much, much more important than before.

Remember that Twin Towers were built without any public input, they were just sort of there. It was another era. So and also, I think it gave people a sense that architecture is important, that it is not business as usual. But architecture should have some ambition. Public space should have an ambition, it should not be just left to your technocrats and bureaucrats to determine the shape of the city.

By the way, I think the impact was on the whole world. Everything changed in architecture after that. People were no longer willing to do it as before. And I think that was sort of one of the focal points that this competition gave to the world that that architecture is important. Planning is not a private business, it should be determined by a democratic voice of all the different interests, which includes developers and agents, the people, you know, all sorts of different constituencies.

Of course, I started with their families by beginning with those who perished. I didn't start with the building, I started by speaking to people, the fathers and mothers, husbands and brothers, you know, that's what moved me. It was about people. And I think that's changed the idea that memories are important, that memory is not just an add on. But memory is a critical space in a city that must be preserved. Because without memory we would be built to a kind of amnesia.

Lizzie Crook: What was it like to speak to the families?

Daniel Libeskind: Oh my God. That was really very sad. As I said, I didn't start by going and measuring, you know, how many subway lines are necessary to go through the site, although that was part of my project, how to bring them together, and the train terminal and what to do with traffic, and how to bring the streets back.

I started with people and I spoke to them and I became friends with a number of people who lost loved ones. And I understood that this pain and this suffering is also part of the site because it happened on this ground in New York, in Manhattan. And I thought that the most important thing would be to bring the space back to focus in a positive sense, in terms of doing something that means something not just in terms of quantities or profits, but in terms of how people would feel.

And I'll never forget, a couple of people came over to me, he lost a son who was a fireman, one of the firefighters, and she lost her daughter who was a flight attendant on one of the aeroplanes. And they showed me a drawing that they had. I'll never forget the drawing, they unfolded a drawing, and I did not know what it was, it just had 1000s of little dots on it. Really, I didn't know what it was. And it was where body parts were on the site, literally hundreds of thousands.

From that time on, I realised I'm not going to treat the site... this is a site that in my mind is a spiritual sacred site, it cannot be just treated like any other site. And you cannot just build the buildings where they used to be. But I understood that. And I followed many of the families, and I was in contact with them throughout the process. And yeah, that really changed my part of it because it could have been any one of us. Who would have been in that building, either working there or delivering something or cleaning the floors or whatever. One could have been one of those 3000 people or so.

Lizzie Crook: Was there ever a feeling that 9/11 could have been the end of tall buildings?

Daniel Libeskind: Oh, yes. You know, the mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, just wanted low buildings. Forget it, you know, New York is a city of towers, it always has been, you know. People said after that attack, I remember, because our offices are right there, right, at the site. People said nobody will ever come back to downtown, companies will move to New Jersey, they'll move to Connecticut.

People don't want to be there anymore. It's that place. But no, it's New York, it's the spirit of New York, New York is about tall buildings. And by the way, New York has the luxury to build tall buildings. Because you know, it's a high-density city with transportation that brings people to work and to play, you know, all around.

By the way, today with a pandemic, people say the same thing. People will not work with offices anymore. Everybody will be home, it'd be remote working. But no, there's no doubt in my mind that New York, like all great cities, has its own traditions. And, you know, it's a kind of capital of the imagination and creativity and that's where people will always come and will do work and be there. Yeah, not for me, that's, you know, the suburban house with a lawn is going to replace the great powers of New York.

Lizzie Crook: How would you say 9/11 impacted skyscraper design?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, you know, one of my responsibilities [for the masterplan] was to write some new parameters for high rise buildings, to make them ecological, to introduce green technology to make sure that they minimise the carbon footprint. So it's not just the aesthetics of buildings, but really the sustainability of buildings, that is part of the buildings at Ground Zero.

And of course, that's a really huge step in a city like New York, to realise that these buildings can no longer be built, like in the old times, you know, wasteful of energy, they have to be smart buildings, they have to really be responsive to the crisis of ecology that we're going through. And we cannot afford to build buildings, like before. So that's a really, very, very much a part of it.

And by the way, you know, just as an added bonus, my parents were basically factory workers, and my father was a printer, right next to the site. And I always thought to myself, what could my parents get from this rebuilding? They never would be in those office towers. You know, they'd be on the subways, they'd be on the streets trying to work and feed their kids.

And I said, what can I give them? I can give them a sense of New York is beautiful, there is an open space or trees, there's water, there are beautiful vistas of the Hudson and the city. Council facilities, a cultural centre being built, there's a beautiful station to go to. So yes, even the symbolic elements. And of course, the northern corner has not yet been built, because it's tower number two. But I thought it would be simple to resonate with people like my parents who were just regular New Yorkers. That was part of how I thought about the site.

Lizzie Crook: Why do you think it is that people still want to build and live and work in skyscrapers?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, first of all, you know, if you don't want to consume more and more land, and keep building, out and out and out and reinforcing cars, you know, fossil fuels and so on, you have to build densely. That's why cities originated. Cities originated because people want to be together.

Everybody wants to be there to share, and improve themselves, get a better job, or learn something new. That's why people flock to cities, it's creativity. Cities have been carved, not by coincidence. The cities are probably the greatest inventions of humanity because people realise that being together, gives you something that you can never get by being, you know, in a monastery alone, somewhere far away.

So, because of that, and because of sustainability, we cannot consume land by building low buildings and eating up what's leftover of the nature we already managed to destroy. It's such a clear way. So it's a necessity. But also there's a magic to tall buildings, beyond the necessity, there is a sort of primordial sense of joy of being able to dominate the city or from a higher perspective.

Le Corbusier thought that the best floor to live on, buildings should not be really higher than the seventh floor because, you know, you're supposed to live on the streets. You're not in the sky. By the way, I live on the seventh floor! But the truth is that when you're in a high rise in a skyscraper, it's just so liberating in many ways. You're so... again, the mythology of being high, and the necessity of building high density, which means tall buildings. It's not about to disappear. We're not about to go backwards and you know live in three-storey houses, two-storey houses.

Lizzie Crook: What do you think architecture's role is in providing closure for victims and the families of victims of such tragic events such as 9/11?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, I think there's no doubt that architecture has a healing role. To build a beautiful space, a place where you can come to, which is a spiritual place, even in just a regular, you know, piece of the city.

But it's a spiritual space when you enter that space, you hear the waterfalls, you see that the buildings, that the great office towers really are far away from you, so that you're in the light, and not in the shadow of the towers, the towers are really of the periphery and form a horizon through which you can also the beauty of New York.

I think that provides a sense of place that, you know, you might not feel the sadness for people who lost loved ones, or the sadness of the attack that killed almost 3000 people, but you feel that there is a sense of integrity, a sense of reality, in the space, and the sense that the space speaks with its own voice.

And by the way, I don't know whether you noticed when Pope Francis came to New York, some years ago, to give his address to all religions, he chose the slurry wall, underground of the museum, to give his ecumenical message. He could have chosen Times Square, St. Patrick's Cathedral or Central Park. But I think the pope understood that this wall speaks through a world about threats, and also about liberties, about freedoms. And I think that was a very moving, moving moment when I was there.

Lizzie Crook: Are you still in touch at all with the families of the victims, or have you ever heard how they have received the site and what it means to them?

Daniel Libeskind: I can tell you that when Ground Zero first opened, when it was completed, it was completed, tower number one and so on. They invited only the families, not the public, and I was there. And so many people came to me, you know, I was anonymous, I was just walking, because they knew me from you know, pictures or they knew who I was, to thank me.

And I still remember the words people said to me: 'thank you, you delivered what you promised. What you said actually happened'. And so of course, you know, I'm a New Yorker, I live and work right next to the site like many people from that era. And I'm glad you know, before the pandemic, this is one of the most visited sites, over 20 million people come through here.

So it's one of the most visited sites, even by New Yorkers. Many people that I met said to me, you know, I live in Brooklyn, or I live uptown, and they never wanted to come back to the site, because it's such a terrible memory. And now that I came to it, it's so great. I feel so much better when I came back to it. So even sometimes New Yorkers were traumatised not to come back to the site. But people have flocked back.

And it's really, I think, a space that is attractive, that has a lot of segments of the city and of memory and also the future, because before we got set, there is all the construction, we are now building tower number five, a residential building, which is fantastic because I always thought that the programme did not contain housing.

But I always thought that that's the kind of site would be that people would live there. And so now, the fifth tower is a beautiful tower that will be also affordable, much of it will be affordable housing, which is so important. So, yeah, this is, of course, it's a site that is evolving, it's not yet finished. After 20 years, it's not finished, but it's pretty much what was intended to be and how lucky to have been part of this process.

Lizzie Crook: What does the success of the site say about the resilience of New York and New Yorkers?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, I think this place, prior to the catastrophe and prior to rebuilding, you know, lower Manhattan was not exactly a cool place to be in. It was, you know, dark skyscrapers after six.

And now, it's really one of the most exciting neighbourhoods, you know, a lot of new housing has been built. Hotels, a lot of retail, schools, a lot of people have moved to the site, a lot of great office buildings have been transformed to residential towers. So it's really, you know, it's now in a new neighbourhood, lower Manhattan is like, one of the coolest, if not the coolest neighbourhood in all of New York, for the next 30 years. So it's really, more than building skyscrapers and more than just building facilities, it's creating a space that could act as a magnet for people to live there. And, of course, by coincidence that people want to live there because there is a sense of a centre of social space that will only increase the time. I'm so lucky to live there.

Lizzie Crook: What were your main lessons or final reflections from working on this project?

Daniel Libeskind: Well, in my view, I always thought there were so many cynics and sceptics about this project. You know, they said, oh, it's gonna be all compromise, and it's all this and it's all that.

But in the end, you know, I am not impressed by the mega projects made by totalitarians. I'm impressed by what a democracy can accomplish with its kind of intense discussion, its disagreements, its strong opinions. And of course, there's no city that has stronger opinions than New York, you know these rough sort of voices. And yet in the end, the fact that this project is so much... the project that I drew the beginning, my first drawing, my intent, that the fact it was to navigate through these complex waters of a democracy shows that first of all democracy is not easy.

But it shows that democracy is the only system worth working in. And that's really my reflection because it's real, you know, what is built in the democratic spirit becomes real. The Twin Towers were never that real because they were a Robert Moses kind of planning, where nobody really participated.

The highways that were built around New York by Robert Moses, but this is something that sort of reinforced my belief that, however difficult the process was, and it was, and however many, you know, conflicts that were at the end, you know, it delivered something, which I'm very proud of, and I think the developers are proud of it.

People who are working there are proud of it, the people who suffered, the loss of their families are proud of it. People who just come by it, who are now living there, you know, it's become a part of the city. I mean, that's really, the greatest indication of working certainly could become part of a true reality and not sort of something artificial.

9/11 anniversary

This article is part ofDezeen's 9/11 anniversary series marking the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center.

The portrait of Libeskind is byStefan Ruiz.

The post "Everything changed in architecture" after 9/11 attacks says Daniel Libeskind appeared first on Dezeen.

#911anniversary #interviews #skyscrapers #all #architecture #features #usa #daniellibeskind #worldtradecenter #groundzero #newyork

Star-Architekt über Berliner Stadtschloss: »Dieses Gebäude ist Fake History« - DER SPIEGEL - Kultur

#Kultur #Berlin #BerlinerStadtschloss #DanielLibeskind #Architektur