YouTube Tipp ▶️

Voice of #WinniethePooh celebrates #100years of the iconic character

https://youtu.be/EI7P7UnMKr0?si=bwHfzMOFtYIkGfxu

#100Years

Ulysses: Celebrating 100 years of a literary masterpiece – BBC

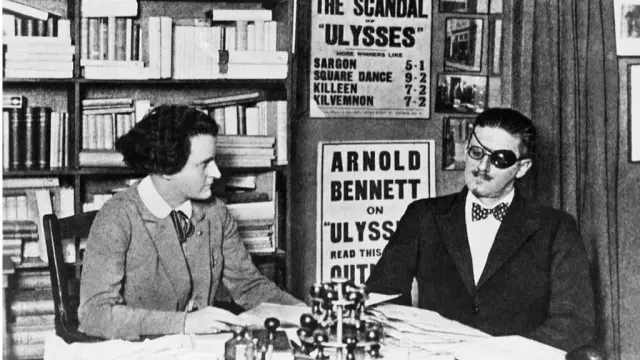

James Joyce met publisher Sylvia Beach in 1920 shortly after he moved to ParisUlysses: Celebrating 100 years of a literary masterpiece

1 February 2022.

By Colm Kelpie, BBC News, NI

In the spring of 1921, Paris bookseller Sylvia Beach boasted about her plans to publish a novel she deemed a masterpiece that would be “ranked among the classics in English literature”.

“Ulysses is going to make my place famous,” she wrote of James Joyce’s acclaimed and challenging novel, written over seven years in three cities depicting the events of a single day in Dublin.

And it did.

On 2 February 1922, Beach published the first book edition of Ulysses, just in time for Joyce’s 40th birthday.

Stylistically dense in parts, it tells the stories of three central characters – Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom and his wife, Molly – and is now celebrated as one of the world’s most influential texts.

‘Tosh’

TS Eliot, writing in 1923, believed Ulysses was “the most important expression which the present age has found”.

But the path to publication was not a smooth one. The novel sparked controversy and was greeted with revulsion by many – even among some in the literary community.

Sylvia Beach’s Paris bookshop was a haven for American expatriates during the 1920s and 1930sVirginia Woolf described it as “tosh”.

Parts had been serialised by US magazine Little Review in 1920, resulting in an obscenity trial that concluded with the editors being fined and ordered to cease further publication. It was also censured in Great Britain.

Beach, the owner of Shakespeare & Company on the Rue Dupuytren, was determined to have it published in book form, which she did, bankrolled in part by her own money on the promise of subscribers.

Writing about the task at the time, she said she had to “put every single centime aside to pay” the book’s printer.

Prof Keri Walsh, outside the modern incarnation of Shakespeare & Company, in ParisProf Keri Walsh, director of the Institute of Irish Studies at New York’s Fordham University, says Beach’s decision to publish turned her into a “culture-hero of the avant-garde.”

“There was a sense that people knew that this was going to be one of the defining books of modernism, so she understood that she would assure her own place in literary history by being the publisher of it,” Prof Walsh tells BBC News NI.

Ulysses: ‘Don’t read the criticism, read the book’Joyce and Beach first met in 1920, not long after he moved to Paris.

He had long left Ireland in self-imposed exile, living in Trieste, Zurich and the French capital.

Beach described that meeting as a powerful moment, says Prof Walsh.

“Joyce was very tired at this point. He had spent so much time fighting to finish Ulysses, and get through [World War One] and survive, he felt she could provide some sort of stability and support for him and his family,” she adds.

“She was much more than a publisher – a banker, agent, administrator, friend of the family. For a very long time that relationship worked well.”

But following disputes over publishing rights, the relationship between Joyce and Beach soured and the latter ultimately ceded the novel’s rights, writes Prof Walsh in The Letters of Sylvia Beach.

Sylvia Beach eventually ceded the publishing rights to Ulysses after her relationship with Joyce souredRandom House published Ulysses in 1934 after the US ban on publication was overturned the previous year.

That marketed it to a bigger audience, but it was 20 years before writers began to “claim” Joyce, says John McCourt, professor of English at the University of Macerata in Italy.

While Joyce was deeply frustrated by the reception Ulysses had received, he was equally unrelenting, adds Prof McCourt.

“He wouldn’t change a comma to make it more acceptable to whatever public taste deemed was OK.

“He saw himself becoming a cause celebre and played it for all it was worth.”

Tips for reading (or attempting to read) Ulysses

Prof John McCourt, University of Macerata, Italy

Nobody is fully prepared to read the book.

If you know something about music that would be a big help.

If you know something about Ireland and its history, that would help.

Don’t try and read it too quickly. Read it out loud as it does come alive.

Editor’s Note: Read the rest of the story, at the below link.

Continue/Read Original Article Here: Ulysses: Celebrating 100 years of a literary masterpiece

#100Years #BBC #BBCNews #Bookshop #ColmKelpie #February21922Published #From2022 #JamesJoyce #LeopoldBloom #LiteraryMasterpiece #MollyBloom #Paris #Publication #PublishedIn1934InUS #Publisher #RandomHouse #ReadingUlysses #ShakespeareCompany #StephenDedalus #SylviaBeach #TSEliot #UlyssesDirty Martin's celebrates 100 years serving Austin

Dirty Martin's celebrates 100 years serving Austin

https://www.kxan.com/news/local/austin/dirty-martins-celebrates-100-years-serving-austin/

#Austin #Local #News #Texas #TopStories #100years #Anniversary #Burger #Cheeseburger #Dirtymartins #Dirtys #Oldaustin #TheDrag #Ut

Una persona autorevole in Europa e nel mondo dovrebbe avere la stessa universale autorevolezza anche in patria. I sondaggi possono premiare un centrodestra democratico, laico e maturo o una destra cristiana che non ha elaborato il lutto di essere diventata ricca con la democrazia repubblicana costituzionale. Il sogno di Berlusconi sulla giustizia italiana lentamente sta sfilacciando i diritti conquistati da altri, con un SNC di 80anni ancora immaturo

Radio News January 1926 #100years

100 anos de Disney.

O noso corazón segue tendo o modo infantil

“The Origin Collection”: a new line celebrating Ducati’s first 100 years

Ducati presents “The Origin Collection”, the new exclusive clothing line celebrating the first 100 years of the Bologna-based manufacturer.

#Ducati #IndustryNews #LatestMotorcycleNews #Manufacturers #100years #Ducati #TheOriginCollection

https://modernclassicbikes.co.uk/the-origin-collection-a-new-line-celebrating-ducatis-first-100-years/?fsp_sid=34078

One of music’s best kept secrets celebrates 100 years, quietly – NPR

One of music’s best kept secrets celebrates 100 years, quietly

The story of Coolidge Auditorium, at the Library of Congress, is one of American ingenuity, cultural integrity and a century of free concerts.

October 25, 20258:18 AM ET, Heard on Weekend Edition Saturday

Tom Huizenga 6-Minute Listen Transcript

The Dalí Quartet, accompanied by Ricardo Morales on clarinet, performs during the Library of Congress’ Stradivari concert in Coolidge Auditorium in 2023. The Library was given a rare set of Stradivarius instruments in 1935.Shawn Miller/Library of Congress

The year is 1925. The Great Gatsby is published, the jazz age is swinging, and on October 28th, a new concert hall opens at an unlikely spot — the Library of Congress, in Washington D.C. If only its cream-colored walls could talk. For 100 years, performers of all stripes have graced the Library stage, from classical music luminaries like Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky to Stevie Wonder, Audra McDonald and Max Roach. Today, it remains one of the capitol city’s most beautiful, best sounding and perhaps best kept secrets.

The idea for a concert hall at the Library of Congress did not stem from congress. It came from philanthropist Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge — and one bespoke piece of bipartisan legislation. “She was indefatigable and intrepid,” says Anne McLean, senior producer for concerts at the Library, “a remarkable woman, six feet tall, a brilliant pianist.” McLean is sitting with me on the stage, overlooking the empty auditorium. To mark the centennial, celebratory concerts and commissions have been heard in the hall all year. But not now. The government shutdown has forced the hall to close its doors, and unless a deal is reached before Tuesday, it’ll be closed on the anniversary itself.

Coolidge was born into a wealthy Chicago family in 1864. She studied music, traveled abroad, married a Harvard-trained orthopedic surgeon and, in 1924, came to Washington to establish a foothold in the nation’s capitol. She approached Carl Engel, the Library’s music chief, about the possibility of adding a small concert hall to the Library’s voluptuous — and voluminous — Thomas Jefferson building, designed after the Paris opera house and completed in 1897. You can’t see the hall from the outside, as it’s tucked inside the building’s Northwest Courtyard.

In 1924, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge wrote her first check to the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, to begin the construction of a new auditorium.Eager to get started, Coolidge wrote a check for $60,000 to the Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, on Nov. 12, 1924. And yet there was no legal mechanism in place for a civilian to make such a monetary gift to the U.S. government. Congress worked quickly, taking only a little over a month to pass a bill allowing such a contribution.

It took less than six months to build the hall itself — the intimate, 485-seat Coolidge Auditorium, with its warm precise acoustics. “There are a lot of secrets to it,” McLean says. “The back wall of the auditorium is slightly shaved to be concave and extremely responsive to string sound. Underneath the stage is hollow. But that hollowness is a factor, as is the cork floor, which was very unusual for its time.” McLean says the sound blossoms in the hall. Keen to spread the sound far and wide, Coolidge even had the building wired for the relatively new medium of radio. She added to her initial sum to establish a fund for the commissioning of new music. Engel dubbed her “The Fairy-God-Mother of Music.”

Construction of Coolidge Auditorium, at the Library of Congress, began in May, 1925. It was finished in time for the very first concert on Oct. 28 of that year. Library of CongressCoolidge was well-connected and fiercely advocated for music. In 1944, she took to the local Washington airwaves with another bold idea. “I could wish for music, the same governmental protection that is given to hygiene, education or public welfare,” she said over WTOP. “How wonderful, if we could have in the cabinet, a secretary of fine arts.”

Coolidge never got her wish, but what she had already created was arguably more important — a living, breathing concert hall that serves as a cultural beacon — preserving history and cultivating new music through commissions.

The Martha Graham Dance Company performs the world premiere of Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring on the stage of the Coolidge Auditorium on Oct. 30, 1944. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation Collection / Library of CongressPerhaps the most famous commission became one of America’s most iconic pieces of music. Aaron Copland‘s ballet Appalachian Spring, written for dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, received its world premiere at Coolidge Auditorium on Oct. 30, 1944. “I think people knew what they were hearing,” McLean says. The ballet would win the Pulitzer prize for music the following year, along with the New York Music Critics Circle Award. It’s hard to imagine a full ballet produced on Coolidge’s modestly-sized stage.

Continue/Read Original Article Here: One of music’s best kept secrets celebrates 100 years, quietly : NPR

#100Years #AaronCopland #CoolidgeAuditorium #Culture #FreeConcerts #Ingenuity #LibraryOfCongress #MarthaGraham #Music #NationalPublicRadio #NPR #TomHuizenga #WeekendEdition

How Leica Developed Its Legendary Rangefinder Cameras https://petapixel.com/2025/08/20/how-leica-developed-its-legendary-rangefinder-cameras/ #camerahistory #oskarbarnack #rangefinder #Equipment #100years #history #analog #leica #News

100 years of Zermelo's axiom of choice: What was the problem with it? (2006)

https://research.mietek.io/mi.MartinLof2006.html

#HackerNews #Zermelo #Axiom #Choice #Zermelo #100Years #Philosophy #Mathematics