The thread about runaway tramcars; what happens when the brakes won’t work?

On this day in 1918 (June 23rd when written) there was an “Extraordinary Tramway Incident” in Edinburgh as a result of which, miraculously, nobody was hurt. This was the days of cable traction, when the city’s public transport wound its way slowly and noisily around the streets hauled by an endless loop of moving cable beneath the setts.

Edinburgh Cable Car on route 2, Gorgie Road. Unknown photographer, 1920, © Edinburgh City LibrariesIt was just after 10 O’clock in the morning and an empty car (they were always called cars, never trams) was standing awaiting its next service at the Braids terminus, near where Comiston Road meets Braid Hills Road. The driver and conductor were on their break in the adjacent shelter (a replacement version of which is still there to this day). But the vehicle’s mechanical brakes had not been fully set and, imperceptibly slowly at first, the car began to creep away down Comiston Road towards the City.

The tramway shelter on Comiston Road, with a cable car waiting at the former line terminus.The driver and conductor gave chase as soon as they noticed but were already too late and were unable to catch it as it began to speed up. The cable which moved the tramcars when in service was attached to by means of a mechanical “gripper” and whizzed anything attached to it along at a rather sedate 9½ mph (to which it was limited by Board of Trade regulations). The downhill runaway quickly passed this limiting speed and quickly caught up with the car running in service ahead of it. Fortunately there were no passengers aboard. The conductress saw the approaching danger, called a warning to the driver, and sensibly jumped for it. The inevitable collision happened and the two cars became entangled together. Luckily neither derailed. Less fortunately the driver – who had heroically stayed at his post – found that the gripper which connected his car to the traction cable had become jammed; the conjoined wreckage was thus firmly attached to the cable and was being hauled inextricably towards busy Morningside at a slightly less than terrifying nine and a half miles per hour. The danger was still real however as this was where Comiston Road changed from rural to dense urban in nature and the driver now had no way to stop at any approaching junctions, for any other tram cars ahead of him or to slow for any obstructions such as pedestrians, cyclists, horses, children crossing or workmen carrying sheets of plate glass across his path like they did in the movies then.

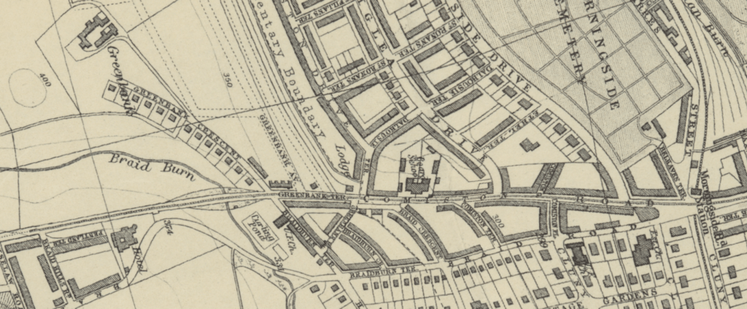

1918 Post Office map of Edinburgh, rotated to align Comiston Road on the long axis (it actually points north:south). The Braids terminus is on the left where the line representing the tramway peters out, Belhaven Terrace on the right at Morningside Station. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandAt Belhaven Terrace, just one mile from where the runaway had started, there was a set of points manned by a pointsman for switching the cars which had terminated at Morningside Station between tracks. The driver managed to call out his predicament to the pointsman as he sailed helplessly past. The pointsman’s hut had a telephone connection to the winding house at Tollcross which was powering the cable and after a brief call the winding engine was stopped. This brought the runaway – and half of the tramway network in the south and west of the city which shared that cable – safely to a halt. It took time to untangle the damaged cars and extricate the gripper from the cable but within an hour and a quarter from the start of the incident the network was back up and running again as if nothing had ever happened. Sadly no further details were reported in the papers

West Tollcross – showing Central Halls on the right and to its left the Tramway Power Station. J. R. Hamilton, 1914. This is a photograph by a member of the Edinburgh Photographic Society © Edinburgh City LibrariesRunaways tramcars were fortunately very rare, but not unheard of. In April 1890 a horse-drawn vehicle had ran away down Montrose Terrace in the east of the city. One of the animals fell but its panicked companion dragged it and the tramcar along the ground a further 1,000ft before coming to rest outside the Abbey Church. “The passengers, who were greatly alarmed, were not, however, injured”. The same cannot be said about the poor fallen horse, as “on examination it was found… [to] not likely be of any more use.” Sadly it was probably a one way ticket to Cox’s Glueworks in Gorgie for that victim.

Horse tramcars on Princes Street, late 19th century. The lighter coloured car is heading for Morningside © Edinburgh City LibrariesOn September 30th 1909 a cable tramcar was involved in a potentially much more deadly accident at Waterloo Place. The car approached the terminus from the direction of Abbeyhill to pick up passengers from a large crowd intending to travel to Musselburgh for the races, but failed to stop in the right place. The driver brought it to a halt further on at the top of Leith Street – outside the General Post Office – and got out to inspect why it had failed to stop in the correct place. The curious and frustrated crowd naturally gravitated towards the vehicle to see what the problem was and if they could board it.

The Waterloo Place tramway terminus for cars to Portobello and onwards to Musselburgh, decorated in 1903 for the coronation visit of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra © Edinburgh City LibrariesPerhaps the driver prodded around underneath too hard, or perhaps an onlooker knocked something they ought not to have, but in an instant the car suddenly lurched back in the direction of Waterloo Place – and the thronging crowd – seemingly attached to the return cable by forces unknown. The vehicle ploughed through the crowd resulting in six people (including three police men) being injured. Again it was lucky that cable haulage did not work at faster speeds. But all was not yet over; “just at that moment a motor car.. appeared on the scene“. The motor became entangled in the front of the tramcar and was dragged along the road by it for thirty yards. The driver jumped clear, narrowly avoiding behind run over by another tramcar coming up Waterloo Place from Regent Road. And then, as soon as it started, the excitement was over: the tramcar released its unexpected grip on the traction cable and the tangle of public and private transportation ground to a halt.

Laurel and Hardy come off worst from an interaction between motorcars and tramcarsOf the four hospitalised, three had been in the car; the driver Archibald Carmichael and his passengers John McArthy and James Paton, through for the day from Gourock and Port Glasgow for the races. The fourth was a pedestrian, Mrs Mathieson of Gayfield Square. This wasn’t the result of black magic or enchantment however as a simple explanation was soon found. As the tramcar had approached Regent Road it had to switch between traction cables by releasing one cable with the rear gripper and grabbing the other with the front gripper (each tramcar had a front and rear gripper to attach itself to the cables.) At it had moved across the junction where Montrose Terrace branched off London Road the gripper had damaged the cable running in the slot between the rails. This had cut into some of the wire strands which had came started to unravel, preventing the gripper from releasing properly when the driver tried to stop on reached Waterloo Place. The fraying cable meantime had run around the pulley and come back towards the now stationary tramcar from the opposite direction and when the tangle of loose strands passed through the released gripper they quickly became tangled in it and enough unravelling wire built up to suddenly start the car in motion again in the return direction.

1907 Post Office map of Edinburgh. Waterloo Place is on the left above Waverley Station. The tramcar had approached from the east (right) and had damaged the cable when it diverted off London Road at Cadzow Place up Montrose Terrace towards Regent Road (the junction is at the right of the map, near where Abbehill Station is marked). Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandIt would prove to be a bad day for the Edinburgh & District Tramways Co. and there had already been an accident earlier that morning when at 11:40AM a car overshot a set of points and collided with the pawl near the Abbey Church between Abbeyhill and Meadowbank. This was an emergency stop device mounted in the traction cable slot beneath the road surface which, if it was hit by a tramcar gripper, detached it from the traction cable and brought the tram to a very instant stop. The pawl was a violent but important measure which prevent the gripper from entering and becoming entangled in the large underground pulleys around which the cable ran. The shock of hitting the pawl in this case was severe enough to snap the car’s front axle. But these were different and more efficient times; the tramway depot at Shrubhill simply sent out a gang with a complete new bogey, which they swapped out at the side of the road in Abbeyhill before getting the car quickly back in service.

Cable tramcar No. 150 passing the Abbey Church in Abbeyhill, c. 1900. It is heading east down London Road towards Meadowbank. SC1592743 via Trove.ScotThe return to service lasted just 15 minutes following the accident before the network had to be stopped again! A tramcar going from the Bridges to Leith Street had collided with another motor car and once again the pair became entangled and took some time to clear. This was the third and final accident of the day.

An altogether more tragic runaway accident took place on Saturday 17th October 1925 when an electric tramcar proceeding down a single line section on Ardmillan Terrace ran away and jumped the points at the foot of the hill, crashing into St. Martin’s Episcopal Church. Young Edward Stirling, aged just 8, had been out to buy a toy train for his brother who was in hospital. He was killed instantly when struck by the tram and was buried in Saughton Cemetery on Wednesday 21st. The tram driver, 3 passengers and another pedestrian were hospitalised. The Corporation sent a wreath and his funeral was attended by Councillor Mancor, Convenor of the Tramway Committee and R. S. Pilcher, the general manager of Corporation Tramways. The Lord and Lady Provost sent a letter of sympathy. A subsequent Board of Trade enquiry found no fault with the tramway equipment or tramcar and did not apportion blame to the driver, who had tried to use the resistance brake to slow the tram followed by the hand brake. There was some popular discontent with the Tramways, a correspondent by the pen name of A. Mother wrote to the ‘News to complain about the speed of the electric trams – “too fast for either safety or comfort“- and to protest about plans to increase their speed even further.

The next runaway took place in spectacular fashion on Saturday June 1st 1929. Miraculously, nobody was injured when car No. 349, waiting at the Liberton terminus with no crew but four elderly passengers aboard ran off down Liberton Brae. Anyone who has ever tried to cycle up (and down) that road can attest just how severe the gradient quickly gets! As the crew availed themselves of the facilities in the terminus shelter they didn’t notice their vehicle slowly begin to roll off down the hill; they had not applied the mechanical hand brake and the pressure had leaked out of the air brake hose causing it to slowly release.

Former tramway terminus shelter at Liberton Gardens, on Liberton Brae.The four passengers (aged 59, 71, 71 and 84) were subjected to a terrifying half mile ride down the Brae before No. 349 came to the corner at Alnwickhill Road, jumped the tracks, slid across the road and pavement and impaled itself on a pole for the overhead wires before caming to rest in the garden of 42 Liberton Brae.

No.349 in the garden of 42 Liberton Brae after the accident of June 1st 1929. © Edinburgh City LibrariesQuite how only one passenger suffered only light bruising and all four had walked away from this defies logic. Indeed the two 71 year olds who had been aboard, a married couple from Leith Walk, simply waited for the next car and carried on home as if nothing else had happened. The house at number 42 was similarly unscathed, although the same could not be said for its garden wall, gate and neat privet hedging.

A News photo of No.349 in the garden of 42 Liberton Brae after the accident of June 1st 1929As a result of this incident protective barriers were installed on the corner outside numbers 42 to 46 where they remain to this day; the dents in their metalwork show they still serve their intended purpose well.

Crash barriers, No. 42-48 Liberton BraeSix years later, in 1935, an accident took place only a few hundred metres down the Brae at Braefoot Terrace. The current collection pole of a tramcar proceeding uphill became dislodged from the current wire and the vehicle lost power and ground quickly to a halt. The trailing SMT bus was following too closely to stop in time and swerved off the road to avoid a collision. Instead it demolished the shopfronts of a James Baxter’s butchers, Adam Smith’s chemist and the branch of the Commercial Bank of Scotland. There were fortunately no major injuries; the butcher’s boy had a lucky escape as he had just been sent outside to clean the windows only to find a thirty-two seater bus baring down on him. He was able to jump clear in the nick of time.

On 25th October 1945, 64 year old Brownlow Grigor of Leith, a Corporation tram driver with 30 years experience was fined £3 by the Burgh Court for “having driven a tram culpably and recklessly“. Grigor was in charge of car No. 42 and had not been paying sufficient attention as he was trying to stow away his thermos flask. He had approached the sharp bend where cars travelling between Morningside and Marchmont turned off Church Hill and onto Greenside Gardens too fast and the laws of physics did the rest. His vehicle jumped the tracks and demolished a 24-foot section of the wall of – coincidentally – number 42 Greenhill Gardens. The embarrassment was all the more severe as this house was St. Bennets, the official residence and private chapel of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Edinburgh and St. Andrews! Grigor’s claim that it was defective rails that were at fault was not upheld.

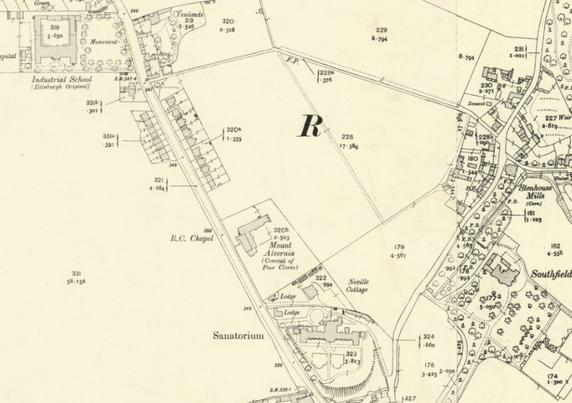

1945 Ordnance Survey town plan of Edinburgh showing the traamway winding its way from Church Hill to Strathearn Place via Greenhill Gardens. Number 42, marked “RC Chapel (Private)” is St. Bennet’s, official residence of the Archbishop. Grigor’s car had jumped the rails as it made the sharp turn in front of it at too high a speed. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandOur last calamity took place in 1951 and it was the heroic figure of James Ferguson, a 53 year old worker from Portobello Power Station, who averted a real catastrophe. The busy tramcar he was on was hit by a lorry near Piershill which injured the driver and caused him to lose consciousness. Ferguson leapt to his feet, ran the length of the car, punched through the glass door to the driver’s compartment with his bare fist and let himself into the cab to disengage the power lever and apply the brakes. Ferguson was treated in hospital for cuts to his hands but was otherwise unscathed.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#Abbeyhill #Accident #Accidents #Ardmillan #CableTrams #Collisions #Edinburgh #HorseTrams #June1 #June23 #Liberton #Suburbs #Tram #Trams #Tramway #Tramways #WaterlooPlace