The thread about the Innocent Railway; How Scotland’s oldest railway tunnel got its name and revolutionised the city’s fuel supply

Writing on the topic of the Scotland Street tunnel, it’s hard not to stumble into the rabbit hole of railway tunnels and look at another, older, rope-worked incline tunnel in Edinburgh – that of St. Leonards – better known by the moniker The Innocent.

At 560 yards, it’s just a little over half the length of Scotland Street and its 1-in-30 gradient is a little less severe than the latter’s 1-in-27. It’s also less roomy, with a 19½ x 14¾ feet cross section vs. 24 x 24 feet. Like Scotland Street, it was worked by gravity downhill and by a static steam engine at the top of the incline to haul waggons uphill. It has a reasonable claim to be Scotland’s oldest railway tunnel – Dundee’s 330 yard long Law Tunnel was completed over a year before it, but traffic started running through the Innocent a few months before that on the Dundee & Newtyle Railway.

First things first – the formal name for the railway was the Edinburgh & Dalkeith Railway so what’s with it being known as the Innocent Railway ? One frequently repeated explanation is that nobody died, or was seriously injured, during the railway’s operational life. Let’s clear that up now – people did die and others were injured on this railway (more on that later), so that’s not where the name comes from. Rather, it comes from how “innocently” backwards the railway, with its plodding horse-hauled traction and ramshackle facilities seemed compared to the rival steam-powered “whizzing, whistling, sorting, buffing and blowing railways and having one’s imagination exasperated by their frantic speed“. It was in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal of January 1846 where the name first appeared in print, as a gentle nickname. By this time the railway was 15 years old but already belonged firmly to a previous generation and had recently purchased by the bigger and more modern North British Railway.

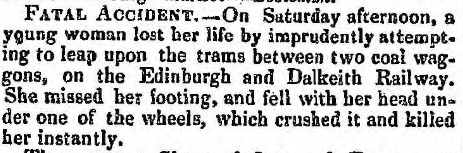

Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, No. 105, January 1846Oddly, even Chambers gets it wrong, sayings “[it] never breaks bones” and “a friend of ours calls it ‘The Innocent Railway’, as being so peculiar for its indestructive character“. Tell that to the young woman who fell between two waggons on Saturday 3rd March 1838 and had her skull fatally crushed! Or to the passengers of the Portobello stagecoach who, on Monday 10th August 1840, had an empty train of waggons collide with their conveyance on a level crossing, injuring a number of them.

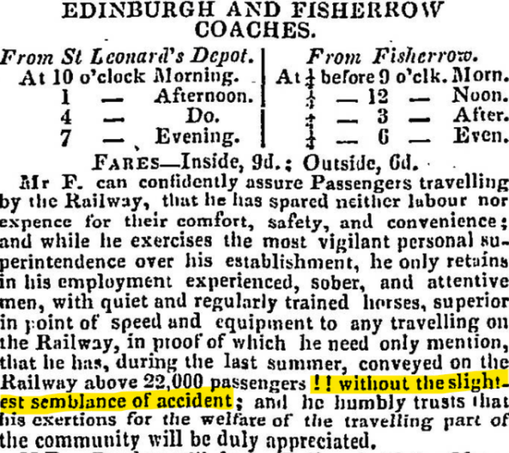

FATAL ACCIDENT – Caledonian Mercury – 5th March 1838Construction wasn’t incident free either. Initial borings of the tunnel commenced at Duddingston in July 1827 and appear to have proceeded steadily and without hitch until February 1829 when a workman was killed and 8 received a variety of injuries – many serious – when 8 yards of masonry archwork, 30 tons of stone blocks, collapsed on them. Robert Inglis lost his life, leaving a widow and two young children; Robert Mercer had his right leg amputated by Mr Liston at the Royal Infirmary; James Gilmour suffered fractured ribs. So the Innocent may have had a lesser rate of incident than its competitors, but it’s evidently not true that there were none and that no serious injuries were incurred or lives lost during its operations. However they were obviously proud of their safety record, as its called out in an 1832 advert:

“Without the slightest semblance of accident”, The Scotsman – 1st September 1832The Innocent opened for business in 1831 and the Edinburgh Evening Courant reported in August that year that it was then “in full operation” with trains of waggons “re-issuing twelve to fifteen tons of coals, with the speed of a mail coach” as they came out of the tunnel on the haulage rope.

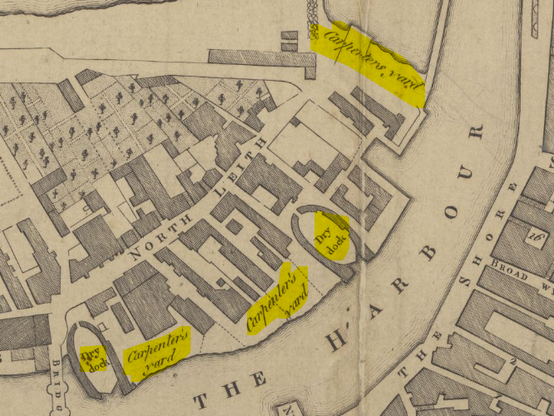

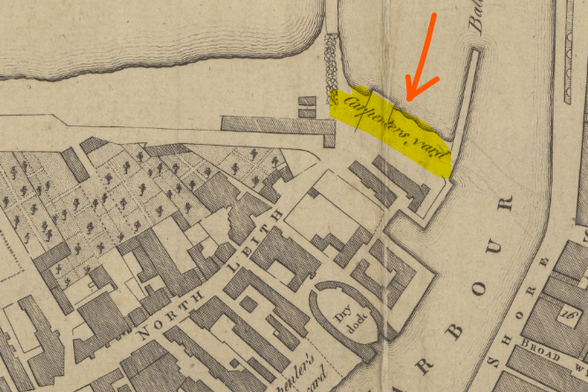

Coal was the reason the railway was built – to bring the black riches from the Midlothian pits around Millerhill, Sheriffhall and south of Dalkeith, and from a branch to Cowpits in East Lothian, into the city of Edinburgh, at a depot in St. Leonards. A further branch extended to the harbour at Fisherrow for import or export of coal – this harbour soon proved not to be a useful destination and so the route was extended on a new branch to the Port of Leith. To the south, the Marquess of Lothian would build an extension across the South Esk river as far as his pits at Arniston at significant personal expense and the Duke of Buccleuch took a branch from Dalkeith to his pits around Smeaton.

The 1825 survey of the route by its engineer, James Jardine, highlighted for clarity. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandIn the mid-1820s, coal could come into Edinburgh either from Lanarkshire – by the Union Canal – from Fife or Northumberland – through the Port of Leith – or locally from East and Midlothian – by cart. However, the winter weather frequently strangled supplies by all 3 of these channels and as a result the growing city frequently suffered from winter fuel shortages, as deliveries dwindled and prices increased. What was needed was a more reliable and cheaper way to bring local coal into the city – a railway was thought to be such a way. Interested gentlemen issued a prospectus for the Mid Lothian Railway from Newbattle to Edinburgh in the winter of 1824. They forecast the best Midlothian coal could be sold in Edinburgh at 8s per ton if brought in by the railway, 40% cheaper when compared with the then market rate of 11s 6d per ton. It was therefore unsurprising that the Lothian “Coal Lords” were all early supporters – Archibald Primrose, 4th Earl of Rosebery; Walter Montagu Douglas Scott, 5th Duke of Buccleuch; Sir John Hope of Pinkie, 11th Baronet; Francis Wemyss Charteris Douglas, 8th Earl of Wemyss & 4th Earl of March; and John Kerr, 7th Marquess of Lothian.

The Mid Lothian Railway soon became the Edinburgh & Dalkeith Railway of the above map. It re-used some of the trackbed of an even older horse-drawn railway, the Edmonstone Waggonway, which had opened for bsiness in August 1818. This line connected pits at Millerhill with a depot at Little France on the lands of Lt. Col. John Wauchope of Edmonstone & Niddrie Marischal. The Innocent threatened Wauchope’s older route and he successfully objected to its 1825 Parliamentary Bill. When a second Bill succeeded in 1826 he changed his mind and came to an agreement with the promoters. This allowed the use of some of his existing trackbed, to have his pits connected to the new railway and also to be paid a share of all the coal being carried across his lands. As a result, the Edmonstone Waggonway was surplus to requirements and was gone by 1831 when the Innocent commenced operations. Edmonstone Coal was soon being advertised for sale at St. Leonards, “direct from the pit head“.

The Innocent found itself a roaring success and was soon carrying over 300 tons of coal a day, all of it (except through the tunnel) by horse power alone. The colliers all provided their own horses and waggons, relieving the railway of having to oversee this aspect of operations. In 1836, a newspaper as far off as the Londonderry Standard reported that “the immense load” of a train weighing 54 tons was moved a distance of 6 miles by just 2 horses.

A Waggonway – at Tanfield on Tyneside. The horse provided the means to move the waggon on the level or uphill. Going downhill it was tethered at the rear and the waggonman would control the speed of descent using the large wooden brake lever. The Coal Waggon – Northumberland Archives Ref. ZMD 78/14But it wasn’t just a case of bringing the coal into the city, the railway also promised to revolutionise how the city’s fuel supply was sold and distributed. At this time, people bought their coal from a preferred merchant and would specify the quality and origin, which depended on the particular pit and seam it was cut from. Some coals produced more light, some more heat, some burned with less smoke, some were cheaper, etc. These were sold like brands, e.g. the Marquess of Lothian’s Great Main Coal or Sir John Hope’s Craighall Jewel Coal, but customers were reliant on the Carters to deliver it to them and had to trust that they were getting what they had paid for. The railway would break the stranglehold of the Carters, who were widely thought to be overpriced and dishonest, selling coal of dubious quality and volumes on the side, and selling direct to the public.

Banner of the Incorporated Trade of the Carters of Leith. © Edinburgh City LibrariesThe railway promised only to supply coal from named and trusted pits (those of the Lothian Coal Lords who backed it, naturally) and hand-picked a selected number of coal merchants to handle the trade from its St. Leonards depot. Neither the railway nor their merchants actually had any stores of coal of their own at the depot, these were the property of the customer’s chosen Collier so it came direct from their stocks. However the company employed a “Weigher“, Robert Gibb, whose job it was to ensure that the weight and type of coal that left the yard matched the customer order; signed and sealed.

Notice in the Edinburgh & Leith Post Office Directory, 1832-33, explaining the operation of the Innocent’s coal sale operation to customers.oGibb soon proved that the Carters were indeed swindling customers and delivering inferior quality and underweight shipments, catching them red handed. He followed a Carter who had had accidentally left his paperwork behind at the depot and watched as a lady in Alva Street took delivery of the load. Making enquiries with her, he found that she had a receipt showing she had paid for 20cwt of the Duke of Hamilton’s Great Lanarkshire Coal from the canal, but he knew from his paperwork that the cart had delivered 18cwt of Sir John Hope’s Cowpits Coal from the railway: the Carter had swapped the paperwork over. The railway was quick to act and took out notices in the newspapers and the Post Office Directory to let it be known that their officers would be following and watching the Carters and that customers should only accept coals with a Weigher’s certificate signed and stamped by Gibb himself. They also let it be known that the dishonest Carter had been turned over to the Sheriff and that any others caught cheating would never again be allowed to transport railway coal.

Caution to the Public Against Fraud in Coals – Edinburgh Evening Courant, 31st March 1832To add further checks against fraud, the Weigher’s certificate would be marked with the time of dispatch and customers were to reject any coal delivered more than an hour after that time. This meant it was unlikely that there had been time to adulterate the load. Customers were also instructed to under no circumstances to allow the carter to keep the certificate after delivery, in case he should try use it again. Any one suspecting foul play was invited to inspect the Weigher’s register at the St. Leonards yard. The Railway was thereby guaranteeing both the quality and weight of the coal received, “to secure to the consumer what he has hitherto been little accustomed to, a knowledge of what kind of coal he buys, and of what price he really pays for it“. And with that, the Innocent Railway had totally disrupted the Edinburgh coal market – forever and for the better. The system was soon further improved, by contracting the management of the sale and delivery of coal to one Michael Fox, one of the line’s original engineers. He promised that all deliveries would be made in his own carts, “always being of the best quality and full weight“.

Michael Fox’s advert for railway coal. The Scotsman – 1st September 1832The railway – or rather Michael Fox again – was also quick to catch on that people would pay to ride along the rails as passengers and that they would bring in additional revenue. Starting in June 1832, he put a carriage on the rails and advertised it at 6d per passenger thus introducing the passenger train to Edinburgh. This was his own initiative and a runaway success, the Railway ended up buying it off him in 1836. His service carried 150,000 passengers in its first year and brought in revenue of £4,000. As a passenger railway, per track mile, this made it busier than the steam-hauled Liverpool & Manchester Railway. By September that year, Fox was advertising a timetabled service between St. Leonards, Sheriffhall and Fisherrow, with inside and outside seats (9d and 6d respectively) and that he had winter-proofed the former to “render them dry and safe from the effects of the weather“.

RAILWAY COACH – Edinburgh Evening Courant – 4th June 1832Michael Fox was obviously something of a serial entrepreneur – in 1835 he was advertising “swimmers’ specials”, trains from St. Leonards that would take bathers to Portobello or Seafield to take the waters. As far as I’m aware, nobody ever troubled to make an illustration of the Innocent Railway at work, so this double-decker horse-drawn rail carriage will have to do.

Engraving of a horse-hauled railway carriage crossing a riveroWhen the technically more advanced North British Railway pushed south from Edinburgh to Berwick, the Innocent at first objected then allowed itself to be bought for the princely sum of £113,000. The NBR ripped up the horse-drawn “Scotch Gauge” Innocent and relaid it as a Standard Gauge steam-powered railway in 1847. They also took on the Marquess of Lothian’s railway as far as Gorebridge and rebuilt this in a similar fashion, thereby adding the adding the first push south of the railway that would eventually become the Waverley Route to Carlisle. The Innocent remained open until 1968 as an important but overlooked branch line into the city for coal, brewery and warehousing traffic. It was steam worked until almost the end, the old J35 engines “manfully struggling up the gradient“, sometimes taking multiple attempts to reach the top. “If they avoided asphyxiation in the hell hole, the crews were rewarded with a good dram from the bond“. The route that they followed is now a popular walking and cycle route, officially known as the Innocent Railway.

A J35 locomotive making the run uphill for the Innocent Tunnel. This was its second attempt, having stalled on the first.As a footnote, the Innocent may not have been so deserving of that name if its plans to tunnel its way north into the city centre had ever come to anything. One option was a 900 yard tunnel emerging in Holyrood Park, running on the surface from there, the other a monster 2,200 yard bore emerging at Waverley Station from the south – a great “what if” of Edinburgh transport history.

Early Edinburgh railways. The Edinburgh & Dalkeith (Innocent) in light blue, the Edinburgh & Glasgow in green, the North British in brown and the Edinburgh, Leith & Granton in Yellow.If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#Coal #Collier #Colliery #DuddingstonCraigentinny #Engineering #Fisherrow #Industries #Leith #Midlothian #NorthBritishRailway #Railway #Railways #Southside #transport #Transportation #Tunnel #Tunnels #Written2023