Beyond the Grave: Burial and the Human Condition in Deep Time

Introduction: Death as a Mirror of Mind

In the tapestry of human evolution, few threads are as evocative as the act of burial. The deliberate interment of the dead signifies more than a practical response to mortality; it reflects cognitive depth, emotional resonance, and social complexity. For early hominins, grappling with death may have been a pivotal moment—marking the emergence of symbolic thought and cultural expression. It is in this reckoning with the finality of life that we catch glimpses of an evolving consciousness, one not purely driven by survival, but by memory, grief, and meaning.

This article delves into the archaeological and anthropological evidence of burial practices among ancient hominins, focusing on three seminal sites: Shanidar Cave, Sima de los Huesos, and the Rising Star Cave system. Each site offers a unique window into the evolving relationship between early humans and the concept of death, hinting at a complex interplay between biology, belief, and behavior. Understanding these practices allows us to reimagine the ancient mind and our shared emotional lineage.

Shanidar Cave: Neanderthals and the “Flower Burial”

Located in the Zagros Mountains of northern Iraq, Shanidar Cave has yielded some of the most compelling evidence of Neanderthal burial practices. Excavations led by Ralph Solecki in the 1950s and ’60s uncovered the remains of ten Neanderthal individuals, some of whom appear to have been deliberately buried. Among them, the discovery of Shanidar IV has become particularly iconic.

Next to the bones of Shanidar IV, archaeologists found clusters of ancient pollen grains, potentially representing specific flower species. Solecki interpreted this as evidence of a “flower burial,” suggesting that Neanderthals placed flowers with their dead—a profoundly symbolic act pointing to emotional depth and cognitive sophistication ([cam.ac.uk](https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/shanidarz?utm_source=chatgpt.com)). Although some have argued that the pollen may have entered the site through rodent activity or natural deposition, the overall context supports a more deliberate interpretation.

Further excavations and re-analyses in the 21st century have strengthened the case for intentional burial. The careful placement of bodies and lack of disturbance from carnivores suggest that Neanderthals were not simply reacting to the presence of the dead but were actively managing death in socially meaningful ways. This insight challenges outdated views of Neanderthals as cognitively inferior and reframes them as complex, emotionally responsive beings.

Sima de los Huesos: A Middle Pleistocene Mortuary Site

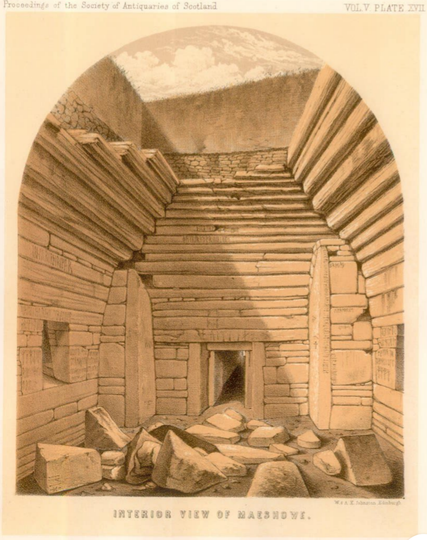

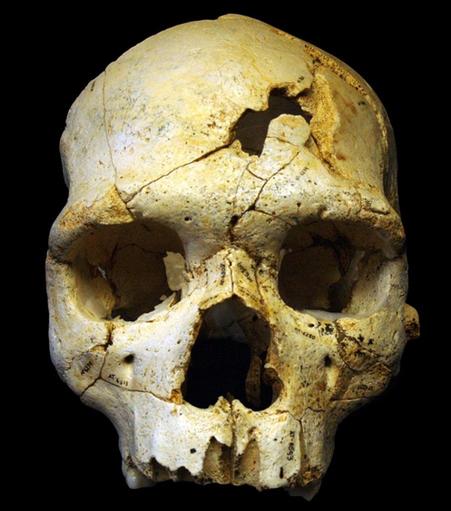

Deep within the Atapuerca Mountains of northern Spain lies one of paleoanthropology’s most haunting sites: Sima de los Huesos, or the “Pit of Bones.” Over 6,500 fossil fragments have been recovered here, representing at least 28 individuals of Homo heidelbergensis. These remains date to approximately 430,000 years ago, making this the earliest known accumulation of hominin bodies in a single context.

What makes this site remarkable is not just the quantity of remains, but the manner of their deposition. The bones were found in a vertical shaft deep within a cave system, suggesting that individuals were intentionally placed or dropped there post-mortem. Taphonomic analyses have revealed breakage patterns consistent with a fall, indicating that bodies were likely lowered or tossed into the pit after death ([phys.org](https://phys.org/news/2025-03-burials-compelling-evidence-neanderthal-homo.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Adding a layer of intrigue, a single finely made handaxe of red quartzite—nicknamed “Excalibur”—was found among the bones. This artifact, too large and unworn to be utilitarian, is interpreted as a symbolic offering or grave good ([sciencedirect.com](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631068305001697?utm_source=chatgpt.com)). If this interpretation holds, it represents one of the earliest instances of funerary symbolism in the human lineage.

Though less visually evocative than Shanidar, Sima de los Huesos may tell a deeper story. The sheer number of individuals represented and the possible inclusion of symbolic items suggest a communal awareness of death and a response that transcends basic hygiene or danger. It suggests the stirring of mortuary tradition and even proto-spirituality among pre-Neanderthal populations.

Rising Star Cave: Contested Homo naledi Burials

In 2013, a team of cavers and scientists working in South Africa’s Rising Star Cave system made a discovery that would shake the foundations of paleoanthropology. The remains of at least 15 individuals of Homo naledi were found in an almost inaccessible chamber called Dinaledi. These fossils, remarkably preserved and undisturbed, presented a new puzzle: how and why were they placed there?

The physical context of the chamber—accessible only through a narrow and perilous route—rules out most natural causes of body accumulation. There are no signs of predator activity, and the presence of articulated skeletons suggests minimal post-mortem disturbance. Over time, researchers proposed a radical hypothesis: Homo naledi may have deliberately placed their dead in this secluded location, engaging in a rudimentary form of burial or body disposal ([nhm.ac.uk](https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/june/claims-homo-naledi-buried-their-dead-alter-our-understanding-human-evolution.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

This claim, if verified, is profound. Homo naledi lived around 236,000 to 335,000 years ago, during a time when they coexisted with early Homo sapiens. Yet their brain size, roughly one-third that of modern humans, challenges assumptions about the cognitive requirements for mortuary practices.

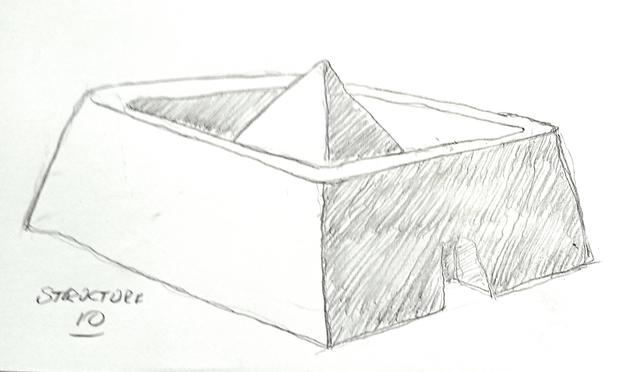

New findings from 2023 have revealed shallow pits containing skeletal remains within the chamber, interpreted as intentional graves. If Homo naledi did engage in deliberate burial, they were doing so independently of other hominin groups with larger brains, suggesting that symbolic behavior evolved more than once in our evolutionary history. Not everyone agrees, and critics point to the need for further evidence and alternative explanations such as accidental entrapment or natural events ([timesofisrael.com](https://www.timesofisrael.com/new-evidence-points-to-neanderthal-burial-rituals/?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Regardless of the final verdict, the case of Homo naledi forces a reevaluation of what it means to be “human” in a behavioral sense and reminds us that evolution is rarely linear or simple.

The Significance of Burial Practices

Burial, in its many forms, offers critical insight into the cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions of hominin life. Across the three cases discussed, several overarching themes emerge:

1. **Cognitive Complexity**: The act of burial implies an understanding of death as a transformation or final state. In some contexts, it may signal belief in an afterlife or a spiritual world.

2. **Social Cohesion**: Burial reflects a strong group identity. The care shown to the dead—whether through floral arrangements, artifact placement, or careful body positioning—indicates that bonds extended beyond life.

3. **Symbolic Behavior**: The use of objects, color (such as red ochre or quartzite), and spatial placement in funerary contexts demonstrates the emergence of symbolic thinking and perhaps language.

4. **Evolutionary Insight**: Studying the diversity of burial practices across species and time periods helps us understand the multiple pathways through which behavioral modernity emerged.

These practices, far from being peripheral cultural details, are central to what makes us human. They mark the emergence of moral frameworks, collective memory, and spiritual imagination. Through burial, the dead remain a part of the living community.

Conclusion: Reflections on Mortality and Humanity

The act of burying the dead transcends mere practicality; it reflects our deep-seated need to find meaning in life and in death. From the fragrant pollen at Shanidar to the enigmatic bodies of Homo naledi, burial practices across hominin species speak to a universal theme: the recognition of mortality and the emotional bonds that outlast it.

As we unearth and interpret these ancient acts, we are not merely studying bones or sediment. We are listening to the whispers of ancient minds—beings who mourned, remembered, and perhaps even imagined a world beyond this one. In these burial sites, we find not just the story of evolution, but the roots of the human soul.

References

- Solecki, R. et al. Shanidar Z: What did Neanderthals do with their dead? University of Cambridge (2023). https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/shanidarz?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Pettitt, P., & Bader, N. New Neanderthal remains associated with the ‘flower burial’ at Shanidar Cave. Antiquity(2017). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/new-neanderthal-remains-associated-with-the-flower-burial-at-shanidar-cave/E7E94F650FF5488680829048FA72E32A

- Rodríguez, J. et al. The emergence of a symbolic behaviour: the sepulchral pit of Sima de los Huesos. Journal of Human Evolution 48, 1–21 (2005). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631068305001697?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Arsuaga, J. et al. Breakage patterns in Sima de los Huesos (Atapuerca, Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science58, 104–113 (2015). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305440315000059?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Dirks, P. et al. Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi. eLife (2023). https://elifesciences.org/reviewed-preprints/89106

- National History Museum. Claims that Homo naledi buried their dead could alter our understanding of human evolution. NHM UK (2023). https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/june/claims-homo-naledi-buried-their-dead-alter-our-understanding-human-evolution.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Hoffmann, H. New evidence points to Neanderthal burial rituals. Times of Israel (2023). https://www.timesofisrael.com/new-evidence-points-to-neanderthal-burial-rituals/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- University of Oxford. Burials provide compelling evidence of Neanderthal social complexity. Phys.org (2025). https://phys.org/news/2025-03-burials-compelling-evidence-neanderthal-homo.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

#AncientMind #Anthropology #Archaeology #BurialPractices #DeepHistory #FuneraryRituals #HomininBurial #HomoNaledi #HumanEvolution #MortuaryArchaeology #Neanderthal #Paleoanthropology #Pleistocene #Prehistory #SimaDeLosHuesos #SymbolicBehavior