At the Dawn of Parenting: An Evolutionary Tale of Love and Survival

Imagine a small band of early humans huddled around a flickering fire on the African savanna 1.8 million years ago. In the dim glow, a young mother cradles her infant, who fusses quietly. There are no cribs or strollers, no formula or diapers – only the tools nature endowed and the ingenuity of a resourceful species. This is the world of early hominin parenting, where raising a child is a feat of survival and a labor of love. In this narrative, we journey back to the Pleistocene to explore how the challenges of prehistoric parenting shaped the course of human evolution. Drawing on anthropological research and evolutionary theory – from Sarah Blaffer Hrdy’s insights into cooperative breeding to modern findings on parental physiology – we uncover how the simple acts of holding, feeding, and nurturing children became pivotal forces in making us human. It’s a story of endurance and creativity, of grandmothers and fathers, of play and community – themes from our distant past that carry surprising lessons for parents today.

Life in the Late Pleistocene: Parenting Without Privilege

In a world with no baby food or nursery rooms, parenting for our Homo erectus ancestors was a full-contact sport. A mother couldn’t lay her baby down in a safe bassinet or duck into a kitchen to warm a bottle. Protection and provision had to be continuous and creative. During the day, mothers foraged wild tubers and fruits, often with infants strapped to their bodies or clinging to their fur or leather slings. Every few hours, the baby’s cries signaled a need for nursing. Milk was the one meal always on hand – and it had to be, for an infant unable to digest tough wild foods relied entirely on mother’s milk for many months. Nights brought their own trials. In the darkness of a world without walls, a sleeping baby left even a few feet away could fall prey to prowling hyenas or leopards. Natural selection had stark rules: infants who were not kept close and protected simply did not survive. As one pediatric scholar put it, “Mothers who left their children alone for more than a few minutes soon had no children… By contrast, the genes that compelled mothers to stay with their children were passed down”. In other words, our very existence as descendants of ancient humans is evidence that our foremothers were attentive, contact-focused caregivers.

Physical closeness was more than a convenience – it was life or death. Early hominin babies, much like human infants today, were born helpless and dependent, far more so than the young of other primates. They required nearly round-the-clock holding, feeding, and cleaning. Anthropologists suspect that early human mothers carried their babies constantly, in arms or perhaps makeshift slings of animal hide or plant fiber. A recent ethnographic analogy comes from the Hadza people of East Africa, whose lifestyles offer a window into the past. Hadza mothers often carry their infants for most of the day from birth until about two to three years old. The payoff of all this holding and carrying is a secure, calm baby: High-touch caregiving leads to less crying and distress. In fact, researchers find that among foragers like the Hadza, “there is a high degree of physical contact and an immediate response to crying” by caregivers – resulting in shorter crying bouts than seen in Western populations. In a Pleistocene context, a quiet baby was also a safer baby, less likely to attract predators or hostile attention.

The challenges extended beyond safety and feeding. Hygiene, for instance, had to be managed without modern diapers or wipes. Parents likely lined cradle-like depressions with soft leaves or moss as primitive diapers, or practiced vigilant “elimination communication,” learning an infant’s signals and holding them away from the body at the right moment. Every task we consider part of parenting today – feeding, soothing, cleaning, teaching – had to be achieved with stone-age resources. Yet, far from merely surviving, our ancestors innovated a parenting style finely tuned to their environment. They slept close to their children (a practice now called co-sleeping) because any other arrangement was unthinkable. They fed on demand because a hungry baby could not wait. And crucially, they did not parent alone.

An Aka father from Central Africa holds his young son. Among the Aka, fathers are famously hands-on, spending nearly half the day within arm’s reach of their infants. This high involvement of fathers and other community members reflects a cooperative breeding system thought to resemble that of early humans.

“It Takes a Tribe”: Cooperative Breeding and Alloparents

One of the most remarkable adaptations that allowed early humans to overcome the immense burdens of child-rearing was the development of cooperative breeding. Unlike other great apes – where mothers are the sole caretakers – humans evolved a strategy in which “it takes a village” was literally true. Mothers had help, and lots of it. Fathers, yes, but also grandmothers, aunts, uncles, older siblings, even unrelated tribe members all pitched in as alloparents (“other parents”). Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, who has championed this concept, notes that human mothers in foraging societies could never have managed to raise our characteristically slow-growing, high-demand offspring without assistance. A human child takes far longer to mature than, say, a baby chimpanzee, requiring an estimated 10–13 million calories to grow to independence – a workload too great for one person. “How did our prehuman ancestresses living in the Pleistocene manage to get those calories?” Hrdy asks. The answer: they rarely did it alone.

Fascinating clues come from studies of contemporary hunter-gatherers thought to model ancient patterns. In the Aka Pygmy communities of the Central African rainforest, for example, childcare is a family and community affair. Anthropologists report that Aka babies have, on average, 14 different caregivers besides their mother – including fathers, grandparents, siblings, and neighbors. Newborn Aka infants are passed from person to person; by the time they are 18 weeks old, they actually spend more time being held by alloparents than by their mothers. Such shared care is not seen as unusual or neglectful – in fact, when one Efe Pygmy mother was asked who cares for babies in her community, she answered simply, “We all do!”. This arrangement, Hrdy explains, is called cooperative breeding. It appears to have deep evolutionary roots in our lineage, emerging by the time of Homo erectus. Indeed, the fossil record hints that by around 1.8–1.7 million years ago, changes in ecology and foraging (such as a shift to harder-to-acquire foods like tubers) made it advantageous for mothers to get help provisioning their young – essentially opening the door for grandmother and others to step in.

The Grandmother Hypothesis is a compelling piece of this puzzle. Originally proposed by evolutionary biologist George C. Williams and later elaborated by anthropologist Kristen Hawkes, this hypothesis suggests that human females’ unusual longevity past menopause evolved precisely because grandmothers who stopped having their own babies could help raise their grandchildren. By foraging and sharing food with their young kin, these post-reproductive women boosted the survival and fertility of their daughters’ children – effectively passing on more of their genes by investing in grandchildren. Mathematical models and field studies support this idea: in foraging groups like the Hadza of Tanzania, the presence of a helpful grandmother correlates with better-nourished grandchildren and allows mothers to have the next baby sooner. Over evolutionary time, such grandmothering could have been “a driving force behind the increased longevity of our species”, as well as our larger brain size – because longer lifespans and the cooperative rearing of slow-maturing, big-brained children go hand in hand. While not all scientists agree on the extent of grandmother’s influence (skeptics note ancient lifespans were shorter on average than today), evidence from humans and even other species (like orcas) shows that grandmaternal support can significantly improve offspring survival.

Cooperative breeding meant that fatherhood too took on a new evolutionary significance. Unlike our ape cousins – male chimpanzees and gorillas that invest little to nothing in caring for kids – early human fathers began to contribute beyond just genes. They might defend the family, provision food, or simply hold and comfort their infants. Intriguingly, human biology seems to have adapted to facilitate this. Modern studies show that when men become active, caregiving fathers, their hormonal profiles shift: testosterone levels tend to drop, presumably to promote nurturing behavior over mating effort. In one far-reaching study from the Philippines, men with higher testosterone were more likely to become fathers, but after their children were born, these men experienced significant declines in testosterone. Fathers who were the most involved in hands-on infant care had the lowest testosterone of all. The authors concluded that human fathers are biologically tuned for parenting – a trait quite rare among mammals. Alongside hormonal shifts, some expectant fathers even undergo couvade syndrome, a sympathetic pregnancy phenomenon where they experience pregnancy-like symptoms (nausea, weight gain, fatigue) when their partner is pregnant. While the causes of couvade are debated (cultural vs. physiological), its existence across cultures hints at the deep psychological and perhaps biological investment men have evolved in the process of child-rearing. All these factors made the family unit of early humans not just a mother-baby dyad but a network – a safety net that allowed our ancestors to raise children who would go on to thrive and spread our species across the globe.

Warm Embrace: Attachment, Closeness, and Infant Survival

Cooperative breeding did not diminish the importance of the mother-infant bond – if anything, it enhanced it by keeping babies alive and well so that bonding could flourish. Central to early hominin parenting was the concept of attachment: the physical and emotional closeness that ensures an infant feels secure. Picture a Pleistocene newborn: after a perilous birth (perhaps aided by a midwife or an experienced older woman of the band), the squalling infant is placed immediately on its mother’s chest. The warmth of skin-to-skin contact and the familiar rhythm of her heartbeat are the only cradle it knows. Across mammals, mother-offspring contact is known to regulate the baby’s physiology – stabilizing temperature, breathing, and heart rate. In humans, this contact may also have fostered brain development and trust. Early humans likely practiced near-constant baby-wearing – keeping infants wrapped against their bodies during daily activities. This not only freed the mother’s hands to gather food or tend a fire, but also ensured that the child’s primitive needs for warmth and safety were met without delay. Evidence from anthropology supports the power of this practice. In cultures around the world that still follow age-old childcare patterns, infants who are carried and promptly comforted tend to cry less and show more stable emotional development.

A mother from the Congo Basin carries her baby while foraging in the forest. In nomadic hunter-gatherer societies, infants are kept close at all times – a likely echo of how early hominin mothers never let their vulnerable babies out of sight. Physical closeness and constant contact helped ensure infant survival in the wild.

Nighttime presented another challenge where ancient instincts prevailed: sleeping arrangements. Today’s debates about co-sleeping versus crib-sleeping have a clear resolution in our evolutionary history. For Paleolithic families, there was no separate nursery (and certainly no baby monitor to listen from afar). Mothers and fathers slept with their babies tucked beside them or on top of them, often through the toddler years. This kept the child safe from cold, predators, or wandering off. It also facilitated on-demand breastfeeding through the night, which both nourished the infant and acted as natural birth control (through lactational amenorrhea) to space out siblings. Researchers who have compared mother-infant sleep in lab settings find that shared sleep leads to more frequent but shorter feedings and arousals, aligning with an infant’s natural needs. In fact, anthropologist James McKenna argues that human infants are biologically designed to sleep in contact with a caregiver, and that co-sleeping (when done safely) is associated with calmer, more self-reliant children in some studies. Our ancestors didn’t need scientific studies to tell them this – the cries of a baby separated in the dark were enough. Simply put, a baby who slept alone in the Paleolithic likely didn’t wake up again. Those who slept attached to mom’s hip did, and passed on genes biased toward close nighttime contact.

Moreover, the early close attachment had long-term benefits. Human infants are born with brains that are only partially finished; the brain doubles in size in the first year after birth. Neuroscientists now know that an infant’s experiences in this critical period – the touch, the responsiveness, the security or stress – can shape brain architecture. A child who feels securely attached (because caregivers respond consistently and warmly) tends to develop better stress regulation and exploratory confidence. It’s poignant to think that under the harsh conditions of the Pleistocene, what most helped our species’ smallest members was not a novel tool or a physical adaptation, but the tenderness of contact and prompt comfort when they whimpered. That early trust, in turn, may have laid the groundwork for humans’ unparalleled social capabilities. As Hrdy eloquently noted, an ape could not evolve such costly, slow-maturing offspring “unless mothers had a lot of help” – and that help allowed those offspring to be raised in an environment rich in love and interaction .

The Littlest Apprentices: Play, Learning, and Growing Up Human

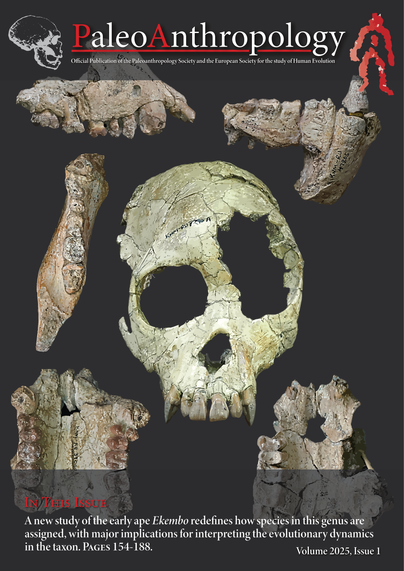

In the flicker of campfires two million years ago, one might have witnessed an extraordinary scene: toddlers and young children playing. Perhaps they were stacking stones, chasing one another, or imitating the adults knapping flint by banging rocks together. To an outside observer, it’s just “horsing around.” But in evolutionary retrospect, this play was deadly serious in its importance. Humans are sometimes called the “most playful” species, and for good reason – our childhood is incredibly extended compared to other animals, giving us years to explore, imagine, and learn through play. Paleoanthropologists believe that even early Homo erectus children had begun to enjoy longer childhoods than their Australopithecine predecessors, though not as prolonged as modern humans . Over hundreds of thousands of years, as human brains grew larger and more complex, our juveniles needed more time to absorb the immense amount of social and practical knowledge required for survival. Play was the natural school for this education.

What does play accomplish for a young hominin? Modern studies of animal behavior provide rich insights. In species from bear cubs to cheetah cubs, those that play more in youth survive better in adulthood. Rough-and-tumble play hones strength and motor skills; pretend or object play stimulates creativity and problem-solving. For early humans, play would have been the training ground for essential adult tasks. A child dragging a stick and giggling may have been rehearsing the motions of digging tubers or throwing a spear. A group of children play-fighting in the dirt were learning social boundaries, cooperation, and conflict resolution in a low-stakes setting. Evolutionary psychologists have long theorized that play is “serious business that serves to train adult minds” – essentially nature’s built-in curriculum for adulthood.

Crucially, human play has a strong social dimension. Our ancestors’ children didn’t grow up in isolated nuclear families; they grew up in multi-age playgroups watched over by multiple caretakers. Older children likely guided younger ones, and younger children provided inspiration and social motivation for older ones to practice caregiving. Anthropologist Peter Gray has noted that in hunter-gatherer cultures, kids are free to play all day in mixed-age groups, and through that play they acquire the skills and values of their society – from sharing to self-control to bravery. Brenna Hassett, a biological anthropologist, points out that humans share with bonobos (one of our close ape relatives) an unusual trait: we keep playing even as adults, a sign of how vital play is to our complex social life. Chimpanzees, by contrast, largely give up play after childhood. Bonobos and humans – the more peaceable, cooperation-loving apes – retain a streak of lifelong playfulness, which helps maintain flexible, tolerant relationships. It’s not hard to imagine that our early ancestors who engaged in playful activities were better at bonding with peers, solving problems together, and coping with unpredictable environments. A game of hide-and-seek in the Pleistocene might literally sharpen the hiding and tracking skills useful in a hunt or in evading predators. A make-believe scenario of “playing house” could allow children to experiment with roles of mother, father, or healer before they actually had to perform them. Through play, the next generation of humans quietly prepared to take on the adult world.

Play also offered a psychological boon: resilience. In the stresses of survival – scarce food, dangerous animals, tribal conflicts – play was a refuge of joy and creativity. It gave children an outlet to process fears and an opportunity to build confidence. Researchers today find that play is linked to healthy emotional development; it’s likely this was true in prehistory as well. A child who could laugh and pretend in even hard times would grow into an adult capable of hope and innovation. Some scientists even speculate that our species’ propensity for imaginative play laid the foundation for later cultural inventions like art, religion, and science – all of which require the ability to envision worlds that don’t yet exist.

The First Village: Community, Emotion, and the Rise of Humanity

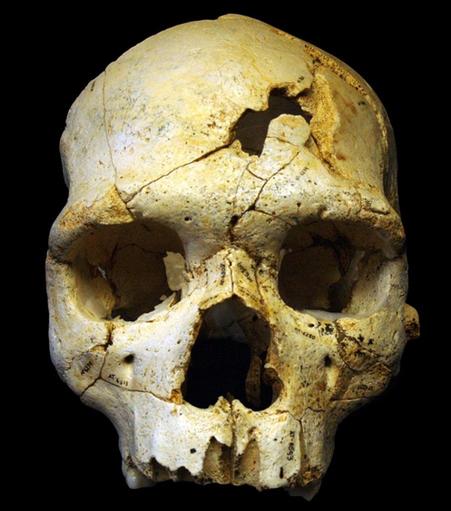

Perhaps the most profound legacy of early hominin parenting is how it forged the emotional ties and community structures that define human societies. By caring for each other’s children, our ancestors wove networks of trust and mutual reliance. This had sweeping implications: it selected for individuals who could empathize, who could anticipate the needs of others, and who found reward in cooperation. In essence, raising children in groups didn’t just produce surviving kids – it produced social adults with unprecedented levels of altruism and group cohesion. Paleoanthropological evidence hints that such prosocial tendencies run deep. A famous discovery at Dmanisi, Georgia (1.8 million years old) uncovered a hominin skull of an elderly individual who had lost all his teeth years before death. He could only have survived that long by others in his group pre-chewing or processing food for him. This toothless elder is seen as one of the earliest signs of human compassion – a being cared for not because he could contribute materially, but because our ancestors had evolved to value one another’s lives. Such care for the weak and vulnerable likely originated around the hearths where infants and parents bonded; once you have emotional attachments and shared childrearing, it’s a short leap to tending to injured hunters or disabled kin. As one science writer noted, we humans are a paradox: natural selection might predict selfishness, yet we observe deep kindness even when there’s no immediate benefit. The roots of that kindness may lie in the primal instincts of mothers, fathers, and helpers to nurture the young – an instinct that spilled over to a general ethos of “all life in our band is precious.”

Communal childrearing also meant communal joy and communal grief. When a child succeeded – took first steps, learned to crack a nut with a stone – the whole group celebrated. When a child fell ill or a mother struggled, the group shared the burden. This fostered emotional resilience not just in the children but in the parents as well. Parental stress was buffered by the knowledge that others “had your back.” Consider a young Pleistocene mother who might feel overwhelmed – her own mother or mother-in-law could step in, giving her respite and guidance. The presence of “alloparents” has measurable benefits even today: studies show that mothers with strong support networks experience less anxiety and depression, and their children often fare better developmentally. It is moving to think that even in the Pleistocene, perhaps around a shared meal of roasted roots, a mother could voice her worries and be comforted by a sister or friend who would take the baby for a while, or by a grandmother who offered wisdom from raising her own young.

Indeed, humans might not have survived the volatile swings of the Pleistocene climate or the dangers of new lands without this collective resilience. By spreading the work and love of raising children among many, communities could endure hardship. If one adult was lost to injury or a hunt gone wrong, the children still had others to feed and protect them. In this way, cooperative parenting was insurance for the species. It also allowed for remarkable flexibility and innovation. With others helping mind the kids, individuals had more freedom to specialize – some could become better toolmakers, others expert foragers, others healers or storytellers – knowing that their offspring were in safe hands for a time. This specialization and sharing are hallmarks of human society and find their genesis in that simple act of sharing a child’s care.

Finally, raising children in a rich social environment likely contributed to one of humanity’s signature traits: our social intelligence. Psychologists suggest that because our ancestral babies had to distinguish not just “mother” and “father” but a whole host of caregivers – each with different voices, faces, and interactions – their developing brains became wired to read many social cues. They learned to “understand others” in a way other apes did not need to. Hrdy argues that this was the cradle of our capacity for empathy and understanding: only a cooperatively raised ape could become the ultra-social human ape, concerned with the thoughts and feelings of dozens of others . In essence, our ability to form communities, cultures, and civilizations might trace back to the nursery – to how we as helpless infants were cared for by a circle of loving kin.

Coming Full Circle: Ancient Lessons for Modern Parents

Our expedition into the past reveals that early hominin parenting was not just a phase of life – it was the crucible of human evolution. By meeting the challenges of raising children under austere conditions, our ancestors unlocked new evolutionary strategies: they lived longer, grew smarter, became more social. In doing so, they left us a legacy encoded not only in our genes, but in our hearts and minds. We carry in us the instincts of the Pleistocene parent: the urge to comfort a crying baby, the impulse to seek help from family or friends when child-rearing feels overwhelming, the joy in watching children play, and the fierce desire to protect them from harm. Modern science continually reaffirms these ancient practices. Close contact, responsive care, breastfeeding, and cooperative support – these are not newfangled trends but time-tested behaviors that promote healthy development. When today’s parents practice skin-to-skin bonding or enlist grandparents in babysitting, they are echoing patterns as old as humanity.

Of course, context has changed. We no longer live in small bands under the stars, and what was adaptive then isn’t always practical now. But the principles endure. Humans are adaptable – that’s another gift of our evolutionary story. As one anthropologist wryly noted, there’s no single “natural” way to raise a child; our species has thrived by being inventive and flexible, from the savannas of Africa to the high-rises of New York. Yet, the core needs of children – love, security, stimulation, social connection – remain constant. We meet them best not in isolation but in community. The notion that a mom and dad alone should fulfill all a child’s needs (prevalent in many industrialized societies) stands in stark contrast to the cooperative breeding model we came from. Perhaps this is why many parents today feel stressed and “burnt out” – we’ve put them in an unnatural situation, “asking the nuclear family to live all by itself in a box,” as Margaret Mead once said, which she warned is “an impossible situation”. The pandemic of recent years underscored this: cut off from support, parents struggled mightily, and mental health issues soared.

The remedy may lie in remembering the wisdom of our ancestors. We can’t resurrect the Pleistocene, nor would we want to romanticize it – infant mortality was high, dangers were real. But we can integrate old and new. Encouraging fathers to take paternity leave and be active caregivers is deeply aligned with our biology (and today we know it strengthens family bonds and child outcomes). Embracing the help of “alloparents” – whether they be grandparents, uncles, close friends, or trusted daycare providers – is not a sign of parental failure but a return to form, creating the “village” that every child and parent deserves. Holding and cuddling our babies, responding to their cries with empathy, and not worrying about “spoiling” them – these instincts built our big brains and compassionate hearts. And letting children play freely – giving them unstructured time to explore with peers – is not wasted time but the very mechanism by which nature allows young minds to blossom.

As we conclude this journey, we arrive at a reassuring insight: modern parents are not alone – they have the strength of an ancient lineage behind them. Every bedtime story told, every skinned knee kissed, every soccer game cheered from the sidelines, carries echoes of those Pleistocene evenings where a circle of adults watched over the youngsters tumbling in the grass, smiling at their antics. The tools have changed (car seats instead of slings, baby puree instead of premasticated tubers), but the heart of parenting hasn’t. It’s still about survival and love. Our ancestors taught us that those two go hand in hand. By loving well, they survived. By ensuring their children survived, they passed love on to the future. So, when you comfort your child tonight or lean on a friend for support, know that you are part of a grand story that began long before written history – a story in which early hominin parents turned the trials of child-rearing into the triumph of humanity.

Sources:

• Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding. Harvard University Press.

• Hrdy, S. B. (2016). “Variable postpartum responsiveness among humans and other primates with cooperative breeding: A comparative and evolutionary perspective.” Hormones and Behavior, 77, 272–283.

• Hawkes, K. et al. (1998). “Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(3), 1336–1339.

• Hawkes, K. (2018). Interview in Smithsonian Magazine, “How Much Did Grandmothers Influence Human Evolution?”

• Salopek, P. (2015). “The Natural History of Compassion.” National Geographic: Out of Eden Walk (dispatch from Dmanisi, Georgia)

• Crittenden, A. N. (2015). Observations of Hadza child care, reported in Nautilus, “The Caveman Guide to Parenting”.

• Gettler, L. T. et al. (2011). “Longitudinal evidence that fatherhood decreases testosterone in human males.” PNAS, 108(39), 16194–16199.

• Divecha, D. (2021). “How Alloparents Can Help You Raise a Family.” Greater Good Magazine, UC Berkeley.

• Hassett, B. R. (2024). “What Does Play Tell Us About Human Evolution?” Popular Archaeology (Winter 2025 issue) .

• McKenna, J. J. (2007). Sleeping with Your Baby: A Parent’s Guide to Cosleeping. (For discussion of co-sleeping benefits in ancestral patterns).

• Pavitt, N. (Photographer). (2018). Hadza grandmother and grandchild (featured in NPR’s Goats and Soda, June 7, 2018) .

• Various authors in Evolutionary Anthropology and American Journal of Physical Anthropology on the Grandmother Hypothesis and cooperative breeding.

#anthropology #archaeology #Biology #children #history #mentalHealth #motherhood #Paleoanthropology #parenting #PreHistory #STEM