#HeartHealth #OralHealth #HeartHealth #OralHealth #CoronaryArteryDisease #OralBacteria #GutHealth #CardiovascularHealth #MedicalResearch #HealthTips #Wellness #PreventiveCare https://mastodon.social/@biohackingpathway/115624696131983624

#PreventiveCare

Doctors say early screening is the only way to stay ahead. Know details https://english.mathrubhumi.com/lifestyle/health/mens-health-over-30-checkups-efdh0a7a?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=mastodon #MensHealth #HealthAfter30 #PreventiveCare #UrologyAwareness

Africa: 60 Million African Adults May Suffer Diabetes By 2050 - WHO: [This Day] Abuja -- The World Health Organization (WHO) has projected that the number of adults battling diabetes in Africa may rise to 60 million by 2050 if current lifestyles and limited access to preventive and primary health services continue unabated. http://newsfeed.facilit8.network/TPBlHw #Diabetes #AfricaHealth #WHO #PreventiveCare #HealthAwareness

The HPV vaccination is one of the most effective ways to protect children and teens from certain cancers and infections 💛

It works best when given before exposure, offering long-term health benefits that last well into adulthood. Learn how it works and why it’s an essential step in safeguarding your child’s future.

👉 Read more: https://zurl.co/aTXeV

#BabyYumYum #BYY #HPVVaccine #ChildHealth #PreventiveCare #ParentAwareness #HealthTips #VaccinationMatters #WellnessForKids

Trusted Family & Primary Care Wellness Center – Sunrise Primary Care

At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we are proud to serve as a leading family wellness center and primary care wellness center, dedicated to supporting the health and well-being of every individual and family. Our mission is to provide personalized, compassionate care that promotes preventive health, holistic wellness, and a balanced lifestyle for patients of all ages.

As a trusted family wellness center, we offer a wide range of services designed to meet the unique needs of each family member, including routine check-ups, nutrition guidance, mental health support, and wellness programs tailored for children, adults, and seniors. At the same time, as a primary care wellness center, we integrate comprehensive medical care with proactive wellness initiatives, ensuring that every patient receives attentive and personalized attention.

Our team at Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness combines experience, knowledge, and compassion to provide a supportive environment where patients can thrive physically, mentally, and emotionally. Education and empowerment are key components of our approach, with workshops, health screenings, and individualized wellness plans designed to help families make informed choices about their health.

Choosing our family wellness center and primary care wellness center means investing in the long-term well-being of yourself and your loved ones. At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we prioritize your health, helping you and your family achieve lasting vitality, balance, and overall wellness.

https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

#FamilyWellnessCenter #PrimaryCareWellnessCenter #SunrisePrimaryCare #HolisticHealth #WellnessJourney #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #PreventiveCare #WellBeing #WellnessCommunity

Trusted Health & Wellness Center | Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness

At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we are proud to be a leading health and wellness center and health & wellness center, dedicated to improving the well-being of every individual and family. Our mission is to provide personalized care that focuses on preventive health, holistic wellness, and a balanced lifestyle for patients of all ages.

As a trusted health and wellness center, we offer a wide range of services including routine check-ups, chronic disease management, nutrition counseling, mental health support, stress management, and holistic wellness programs. Our team at Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness combines compassionate care with modern medical practices to ensure that every patient receives comprehensive attention. Whether you are visiting our facility or participating in our wellness programs, our goal is to empower you to take control of your health and achieve long-lasting vitality.

Education and proactive care are at the heart of our approach. Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness provides workshops, health screenings, and individualized wellness plans to help patients make informed decisions about their well-being. By choosing our health & wellness center services, you are investing in a healthier, more balanced future for yourself and your family.

https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

Experience the difference of a dedicated health and wellness center that prioritizes your needs. Join Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness today and take the first step toward a healthier, happier, and more vibrant life.

#HealthAndWellnessCenter #HealthWellnessCenter #SunrisePrimaryCare #WellnessJourney #HolisticHealth #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #PreventiveCare #WellBeing #WellnessCommunity

Comprehensive Wellness Center Services at Sunrise Primary Care

At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we are proud to offer exceptional wellness center services as a leading primary care wellness center, family wellness center, and health & wellness center. Our mission is to support the well-being of every individual and family by providing personalized care that promotes overall health, preventive care, and a balanced lifestyle.

Our wide range of wellness center services includes routine check-ups, chronic disease management, nutrition counseling, mental health support, stress reduction programs, and holistic wellness plans. At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, our experienced team combines compassionate care with modern medical practices to ensure comprehensive attention to every patient’s physical and mental health needs. By integrating primary care with specialized wellness services, we empower patients and families to achieve lasting vitality and improved quality of life.

Education and proactive care are central to our approach. Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness provides workshops, health screenings, and individualized wellness plans designed to help patients make informed choices about their health. Choosing our wellness center services means investing in a healthier future, where each family member can thrive physically, emotionally, and mentally.

Experience the difference of a dedicated primary care wellness center and family wellness center that prioritizes your needs. Join Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness today and take the first step toward a healthier, happier, and more balanced life.

https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

#WellnessCenterServices #PrimaryCareWellnessCenter #FamilyWellnessCenter #HealthAndWellnessCenter #SunrisePrimaryCare #HolisticHealth #WellnessJourney #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #PreventiveCare #WellBeing

Your Trusted Primary Care Wellness Center – Sunrise Primary Care

At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we are proud to be a leading primary care wellness center and family health & wellness center, dedicated to supporting the well-being of every individual and family. Our mission is to provide personalized, compassionate care that promotes overall health, preventive services, and a balanced lifestyle for patients of all ages.

As a trusted primary care wellness center, we offer comprehensive services including routine check-ups, chronic disease management, nutrition guidance, mental health support, and holistic wellness programs. Our team at Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness ensures that each patient receives attentive care, addressing both physical and mental health needs in a safe and welcoming environment. By integrating primary care with wellness programs, we empower patients to achieve long-lasting vitality and improved quality of life.

Education and proactive care are at the heart of our approach. Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness provides workshops, health screenings, and individualized wellness plans to help patients make informed decisions about their health. Choosing our primary care wellness center means investing in a healthier future, where every family member thrives physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Experience the difference of a dedicated primary care wellness center that prioritizes your needs. Join Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness today and take the first step toward a healthier, happier, and more balanced life.

https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

#PrimaryCareWellnessCenter #FamilyWellnessCenter #HealthAndWellnessCenter #SunrisePrimaryCare #HolisticHealth #WellnessJourney #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #PreventiveCare #WellBeing

Trusted Family Wellness Center & Health Care at Sunrise Primary Care

At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we are proud to serve as a leading family wellness center and health & wellness center, dedicated to supporting the health of every family member. Our mission is to provide personalized, compassionate care that promotes overall well-being, preventive health, and a balanced lifestyle for individuals of all ages.

As a trusted family wellness center, we offer a wide range of services including routine check-ups, chronic disease management, nutritional guidance, stress management, and holistic wellness programs. Our experienced team at Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness ensures that each patient receives comprehensive attention, addressing both physical and mental health needs in a safe and welcoming environment. We believe that promoting health for the entire family fosters stronger bonds, better habits, and long-lasting vitality.

Education and empowerment are key components of our approach. Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness provides workshops, health screenings, and customized wellness plans to help families make informed decisions about their health. By choosing our family wellness center, you invest in a future where every family member thrives physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Experience the difference of a dedicated health & wellness center and family wellness center that prioritizes your family’s needs. Join Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness today and take the first step toward a healthier, happier, and more balanced life for the entire family.

https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

#FamilyWellnessCenter #HealthAndWellnessCenter #SunrisePrimaryCare #HolisticHealth #WellnessJourney #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #WellBeing #PreventiveCare #WellnessCommunity

Comprehensive Care at Your Trusted Health & Wellness Center

At our health & wellness center, we combine compassionate medical care with holistic wellness programs to ensure comprehensive support for all patients. Whether it’s routine check-ups, chronic disease management, nutrition guidance, or stress reduction strategies, Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness offers a safe and nurturing environment tailored to your unique health needs. Our experienced team believes in addressing the root causes of health concerns and empowering patients with the knowledge to make informed decisions about their lifestyle and wellness.

Education and proactive care are at the heart of our approach. Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness provides workshops, screenings, and individualized wellness plans designed to help you take control of your health journey. By choosing our health & wellness center, you are investing in a future filled with vitality, balance, and lasting well-being. Our goal is to make every patient feel supported, informed, and motivated to achieve optimal health.

Experience the difference of a dedicated health & wellness center that puts your needs first. Join Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness today and take the first step toward a healthier, happier, and more balanced life.

https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

#HealthAndWellnessCenter #SunrisePrimaryCare #HolisticHealth #WellnessJourney #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #WellBeing #MedicalCare #PreventiveCare #WellnessCommunity

Comprehensive Care at Your Trusted Health and Wellness Center At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we are dedicated to providing exceptional services at a leading health and wellness center. Our mission is to support every individual in achieving optimal health through personalized care, preventive services, and holistic wellness programs. We understand that true well-being goes beyond treating symptoms—it’s about fostering a balanced lifestyle, mental clarity, and physical vitality. Our team of experienced professionals at Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness combines compassionate care with the latest medical practices to ensure that every patient receives comprehensive attention. From routine check-ups to specialized wellness plans, our center is designed to cater to diverse health needs. Whether you are seeking guidance on nutrition, stress management, chronic disease prevention, or fitness optimization, our health and wellness center provides a safe and supportive environment for your health journey. At Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, we also emphasize education and empowerment. We believe that well-informed patients make better decisions about their health. That’s why our wellness programs include workshops, health screenings, and individualized counseling sessions to help you understand and take control of your well-being. Choosing our center means investing in a healthier future, supported by a team that genuinely cares about your physical and mental wellness. Experience the difference of a health and wellness center that prioritizes you. With Sunrise Primary Care & Wellness, you are not just another patient—you are part of a community committed to lasting health, vitality, and balance. Join us today and take the first step toward a brighter, healthier tomorrow https://sunrisepcwellness.com/

#HealthAndWellnessCenter

#SunrisePrimaryCare #WellnessJourney #HolisticHealth #PreventiveCare #HealthyLifestyle #PatientCare #WellBeing #MedicalCare #WellnessCommunity

🍂 **6 quy tắc sức khỏe trong mùa thu**

Mùa thu đến với tiết trời mát mẻ nhưng cũng mang đến nhiều thách thức cho sức khỏe, đặc biệt với người cao tuổi và những người có bệnh nền.

Hãy chủ động bảo vệ sức khỏe trong mùa chuyển tiếp quan trọng này! 💪

#AutumnHealth #MuaThu #SứcKhỏeMùaThu #HealthTips #PreventiveCare #HealthyAging #WellnessTips #SứcKhỏeCộngĐồng

https://vietnamnet.vn/6-quy-tac-suc-khoe-trong-mua-thu-2457143.html

SCAB Pharmacy Ltd successfully conducted a Free Health Screening today at Navrongo Prisons! Our dedicated pharmacists provided essential services such as blood pressure checks, sugar monitoring, weight checks, and informative talks on hypertension and diabetes to support community health.

Thank you to all participants and our passionate team for making a positive impact! Together, we champion wellness and preventive care in our communities.

Check out the event highlights and photos below! For more information on upcoming programs, visit our page or contact us at 0247210265 / 0556632253 / 0532347111.

Let's join hands to foster a healthier Ghana!

#HealthScreening #CommunityHealth #Navrongo #PublicHealth #Wellness #HealthyLiving #HealthTips #WellnessJourney #HealthForAll #PreventiveCare #HealthAwareness #HealthCheckup #PharmacyCare #HealthyGhana #WellnessCommunity #SCABPharmacy #HealthFirst #BloodPressureCheck #SugarMonitoring #Wellbeing

The importance of #preventivecare has become increasingly recognized as a means to improve health outcomes, enhance the quality of life, and reduce the financial burden on healthcare systems.

Preventive Care: The Key to Reducing Healthcare Costs and Improving Health Outcomes.

https://www.alliedacademies.org/articles/preventive-care-the-key-to-reducing-healthcare-costs-and-improving-health-outcomes-31667.html

via Instapaper

𝗡𝗮𝘃𝗿𝗼𝗻𝗴𝗼 𝗣𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗛𝗲𝗮𝗹𝘁𝗵 𝗦𝗰𝗿𝗲𝗲𝗻𝗶𝗻𝗴 — 𝗙𝗿𝗲𝗲 𝗖𝗼𝗺𝗺𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝗘𝘃𝗲𝗻𝘁

Join us on 31/10/2025 at 9:00 AM for a health screening at Navrongo Prisons. All inmates and staff are invited for education and basic checks.

𝗪𝗵𝗮𝘁’𝘀 𝗵𝗮𝗽𝗽𝗲𝗻𝗶𝗻𝗴

- Health talk on hypertension and diabetes

- Blood pressure checks

- Weight checks

- Blood sugar monitoring

𝗩𝗲𝗻𝘂𝗲

- Navrongo Prisons (On the premises of the Prison Office)

𝗖𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗮𝗰𝘁 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗺𝗼𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝗳𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻

- 024 721 0265

- 055 663 2253

- 053 234 7111

𝗠𝗲𝗱𝗶𝗰𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗽𝘂𝗿𝗰𝗵𝗮𝘀𝗲𝘀

- Buy medicines at SCAB Navrongo Station @ Navrongo Hospital

- Order online: www.scabpharmacy.com — home delivery available

Please come early, bring any current medications and medical records if available.

#NavrongoHealth #PrisonHealthScreening #HypertensionAwareness #DiabetesAwareness #BPCheck #SugarMonitoring #CommunityHealth #SCABPharmacy #HealthForAll #PreventiveCare #KnowYourNumbers #HealthyNavrongo

"🌟 Philanthropy strengthens wellness!

💉 Vaccination Rewards provides vaccine incentives and digital tools that help communities make informed health choices.

🌱 Together, we build healthier, empowered communities.

🔗 https://vaccinationrewards.org/

#VaccinationRewards #PhilanthropyInAction #CommunityHealth #WellnessTools #SmartHealth #PreventiveCare #HealthIncentives #DigitalWellbeing #HealthEducation #EmpoweredCommunities #WellBeingMatters #WellnessInnovation #InformedDecisions #CommunityWellness"

"🏠 Transitional housing builds stability!

💡 Vaccination Rewards provides tools and incentives that support health and wellness for those in temporary housing.

📊 Access to resources improves resilience and community strength.

🔗 https://vaccinationrewards.org/

#TransitionalHousing #CommunitySupport #VaccinationRewards #SafeHousing #HealthAndWellness #EmpoweredCommunities #WellnessTools #StrongerTogether #PreventiveCare #HealthyLiving #InformedChoices#AccessibleHealth #SupportiveServices#HousingEquity"

⚡ Burnout isn’t just “stress”: human body cannot run a marathon at a sprint pace ⚡

A few years ago, I hit a wall. As an engineer, I prided myself on solving the unsolvable, taking on complex challenges, and never backing down. But somewhere along the way, I crossed a threshold I didn’t see coming.

The signs were subtle at first: fatigue, brain fog, impatience, apathy about work I once loved. Before long, even the smallest tasks felt like climbing a mountain. My creativity dipped. My confidence wavered. My balance at home frayed. The impact wasn’t just professional; it was deeply personal.

Engineers are especially vulnerable to burnout. We often work in high-stakes environments with tight deadlines, shifting requirements, and pressure to be “always-on.” Our minds are our tools, and when those tools are strained, everything else suffers.

👉 Prevention must come first. It is far better to recognise the early warning signs and intervene than to wait until the damage is done and try to rebuild.

Here are a few strategies I’ve learned (the hard way):

- Set boundaries: say no when your plate is full (I’m still working on this)

- Block time for rest (yes, actual breaks)

- Delegate or outsource non-core tasks

- Stay connected with peers, mentors, or mental-health advocates

- Reflect regularly (daily or weekly) to catch warning signs early

Also, I strongly encourage everyone to watch this documentary: “Burnout - When does work start feeling pointless?” https://youtu.be/raVms8w61No?si=-d_qpOgYICfG5UJu

It offers powerful perspectives on burnout: how it develops, how it affects lives, and what can be done.

Let’s shift the conversation: let’s talk preventive care, not just crisis management. If you’ve ever experienced burnout (or are going through it), you’re not alone. Sharing our stories can be the first step toward change.

#Burnout #EngineerLife #MentalHealth #WorkLifeBalance #PreventiveCare

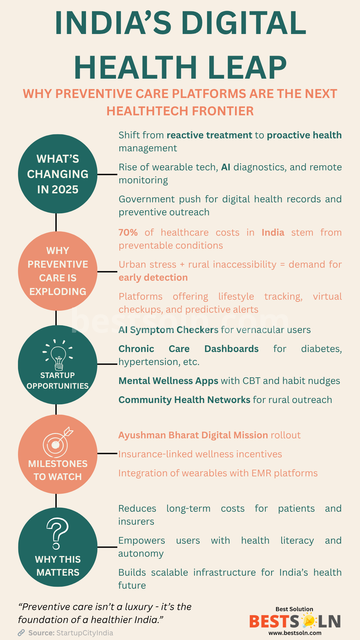

🩺 India’s next healthtech wave isn’t reactive, it’s preventive.

70% of healthcare costs stem from preventable conditions.

Startups are building AI checkers, rural wellness apps & chronic care dashboards.

Here’s why preventive care is the next digital leap 👇

🔗 For more such content, checkout https://bestsoln.com

#Healthtech #PreventiveCare #DigitalIndia #SaaS #BestSolution #Bestsoln

"🍎 Nutrition is key to wellness.

Vaccination Rewards connects communities to 300+ vaccine incentives that support healthy decisions. 🌟

🔗 https://vaccinationrewards.org/

#NutritionSupport #VaccinationRewards #HealthyLiving #HealthIncentives #SmartHealth #CommunityWellness #WellBeingMatters #PreventiveCare #DigitalHealth #LifestyleChoices #NutritionAwareness #HealthyChoices #FoodForHealth #AccessibleHealth #WellnessInnovation #EmpoweredCommunities #NutritionEquity #StrongerTogether #HealthEducation"