“Bobby.. have you been playing with access codes again?” – illustration ‘

Night of the Hackers‘, Newsweek, November 12th, 1984

This is the second in a series of blogs I’m writing about those times over the years that journalists got too close to the world of hackers and became part of their own news story. You can find the first entry, about the hacking of an Iowa university for a TV special, right here.

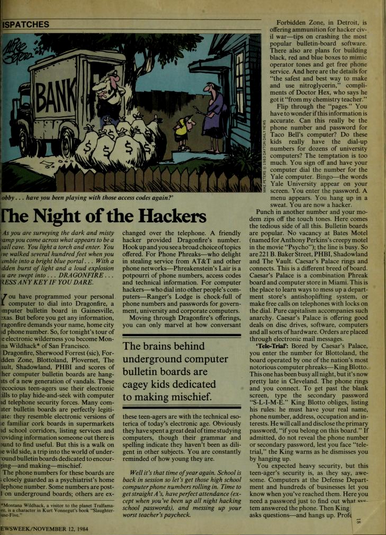

Night of the Hackers

I’ve written about how 1983 was the year that America woke up to the concept of hackers and became in equal parts fascinated with and fearful of hacking itself.

By 1984 journalists gradually moved from simply regurgitating the same short list of infamous hacking incidents or information gleaned from interviews with prominent early hackers who were caught, to chasing down their own stories, getting in amongst hackers in the wild.

Richard Sandza, a reporter for Newsweek, took on the identity of computer whiz-kid “Montana Wildhack” in late 1984 and decided to start dialling up hacker bulletin board systems (BBSes) across the US, so that he could see what hackers were discussing in private and what kinds of illicit information they were sharing.

Moving through Dragonfire’s offerings, you can only marvel at how conversant these teenagers are with the technical esoterica of today’s electronic age. Obviously they have spent a great deal of time studying computers, though their grammar and spelling indicate they haven’t been diligent in other subjects. You are constantly reminded of how young they are.

“Well it’s that time of year again. School is back in session so let’s get those high school computer phone numbers rolling in. Time to get straight A’s, have perfect attendance (except when you’ve been up all night hacking school passwords), and messing up you worst teacher’s paycheck.”

‘Night of the Hackers‘, Richard Sandza, Newsweek, November 12th, 1984

Richard Sandza shared with Newsweek readers the names and general location of many of the prominent underground BBSes of 1984, the names of hackers who ran or were posting on some of the BBSes and some of the topics being discussed. Posing as a hacker he chatted with denizens and operators of the BBSes he picked through for his article.

‘

Night of the Hackers‘, Richard Sandza, Newsweek, November 12th, 1984

I think this subterfuge along with the collection and disclosure of information by Sandza angered the US hacking scene at the time, any outsiders gathering information on hacking or hackers back then was labelled a “narc”, regardless of whether they were actually law enforcement or not.

The article lists the states various boards are located in and titbits of information about the content on the boards that would inevitably provoke pressure on US law enforcement to act. The article includes details such as that “Ranger’s Lodge is chock-full of phone numbers and passwords for government, university and corporate computers” and that on a Florida based BBS called Plovernet “amid a string of valid VISA and MasterCard numbers are dozens of computer phone numbers and passwords”.

An educated guess would be that the way Richard Sandza wrote about the hackers and their world probably angered them just as much.

In the article Sandza notes that the hackers he observes “have spent a great deal of time studying computers, though their grammar and spelling indicate they haven’t been diligent in other subjects” and that reading messages on the boards he was “constantly reminded of how young they are”.

You have to wonder if this information is accurate. Can this really be the phone number and password for Taco Bell’s computer? Do these kids really have the dial-up numbers for dozens of university computers? The temptation is too much. You sign off and have your computer dial the number for the Yale computer. Bingo — the words Yale University appear on your screen. You enter the password. A menu appears. You hang up in a sweat. You are now a hacker.

‘Night of the Hackers‘, Richard Sandza, Newsweek, November 12th, 1984

All in all ‘Night of the Hackers’ was an interesting article that gave a whistle-stop tour of some genuine underground hacker haunts of 1984, perhaps revealing a little too much in the process.

‘

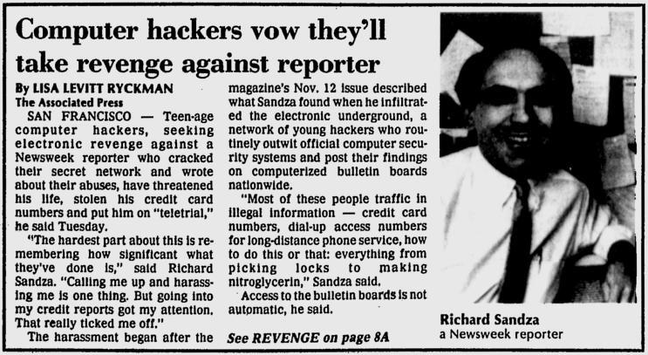

Computer hackers vow they’ll take revenge against reporter‘, Lisa Levitt Ryckman, Gainesville Sun, 5 December, 1984

What happened next was probably predictable to anyone who knew the hacking scene well back then, but I imagine came as a bit of a shock to Richard Sandza.

The Revenge of the Hackers

‘

The Revenge of the Hackers‘, illustration, Newsweek, December 10th, 1984

Less than a month after ‘Night of the Hackers’ was published in Newsweek Richard Sandza had written a follow up in the magazine, ‘The Revenge of the Hackers‘, to document the personal fallout his initial article had caused. As Sandza observed in his follow up article, “within days, computer “bulletin boards” around the country were lit up with attacks on NEWSWEEK’s “Montana Wildhack” (a name I took from a Kurt Vonnegut character), questioning everything from my manhood to my prose style”.

In naming names, both BBSes and hackers, and trespassing throughout the back alleys of the burgeoning hacker scene of late 1984, Richard Sandza had essentially kicked a hornet’s nest and outraged hackers seemed determined to out-do each other in terms of exacting revenge.

The Associated Press quote Sandza in an article that I found in the Gainesville Sun on December 5th of 1984 as saying “I think the ones who are really ticked off feel threatened by this. Some said their parents read the article and shut down their bulletin boards. Others said they felt my reporting was not really fair because I was ripping them off because I wasn’t a hacker and phone ‘phreak'”

Sandza documents in ‘The Revenge of the Hackers‘ that “the hackers of America have called my home at least 2000 times” and that he was notified by a friendly hacker that “someone has broken into TRW and obtained a list of all your credit-card numbers, your home address, social-security number and wife’s name and is posting it on bulletin boards around the country”.

UPI and others reported on a BBS post by a hacker angry about the first Newsweek article, ‘I’m sure you guys have heard about Richard Standza (sic) … He’s the guy who wrote the obscene story about phreaking in NewsWeek (sic). Well my friend did a credit card check on TRW … try this number, it’s a VISA … Please nail this guy bad … Captain Quieg (sic).’

In parallel with this ad-hoc harassment was what was known as a “teletrial” or “tele-trial”, organized through, and taking place on, the Dragonfire BBS. According to the AP, “Sandza said he was put on teletrial on a Gainesville, Texas, bulletin board known as Dragonfire, with a prosecutor called Unknown Warrior and a judge known as Ax Murderer”.

Sandza described a teletrial as “a video-lynching in which a computer user with grievance dials the board and presses charges against the offending party”, in this case the charge against the Newsweek reporter was “endangering all phreaks and hacks”.

He has not abandoned Montana Wildhack, the alter ego that carried him into the computer underground when a Silicon Valley source first gave Sandza a few hackers’ bulletin-board telephone numbers. Logging on as Wildhack, Sandza has put up a spirited defense as he is subjected to “teletrial” on the underground BBS (Bulletin Board System) called Dragonfire. The charge, in the language of his anonymous accusers, is “endangering hacks and phreaks” — the odd spelling is a reference to “phonephreaks,” or the hackers who use electronic tones to steal long-distance telephone time. The rules of the trial are rigorously argued, with Ax Murderer sitting in as judge and Storm Bringer offering his services as public defender should Sandza not locate suitable counsel.

‘Hack Attack‘, Cynthia Gorney, Washington Post, December 6th, 1984

Teletrials are an absolutely fascinating topic and this incident is essentially the only time the practice broke out of the computer underground scene into mainstream media. They were, by all accounts, half in-joke and half a means for specific BBSes to self-police, a threat against scene transgressions, a way to maintain basic social order and discourage narcing.

Teletrials were apparently the creation of King Blotto, of the hacker BBS Blottoland. While teletrials are said to have peaked as a practice in the mid 1980’s I still heard the term used actively on IRC in the 90’s.

I tracked down an angry response to a history of the hacking underground article by notorious hacker charlatan Captain Zap that had been published in 2600 Magazine in 1988. The response highlights what the writer sees as various inaccuracies in the article by Zap, including his account of teletrials.

As for Richard Sandza, Tele-Trial still existed at the time of the publishing of his articles for Newsweek. The “Tele-Trial” he was put on was simply a conference of abusive kids who felt that he had given hackers unfair treatment. In retaliation they threatened him: a Captain Quieg posted his credit report and numerous kids ran up bills on his credit cards, sending assorted junk to his house.

Hackers cannot “perform the destruction” of anyone. All they can do is scare the shit out of “normal” people who are shocked that a bunch of kids can get their unlisted number, credit cards, and various other records, and abuse them.

In any case, Sandza is something of an exception since he managed to piss off a large percentage of people who were in a position to make life hard for him in return. Most people who disagree with him can write a complaint to Newsweek, but if you have the ability to bring your displeasure to his personal attention, in a way that will ensure he gives notice to it, wouldn’t you do the same thing? After all, it isn’t Newsweek you’re mad at, it’s Richard Sandza. Some of you probably wouldn’t, but that’s one of the fringe benefits of being a hacker. Instead of being bound by “the system’s” rules and regulations, you can get around it and let your conscience be your guide (if you happen to have a conscience).

‘A Reader’s Reply‘, Rancid Grapefruit, 2600 Magazine, Summer 1988

It is interesting to me that even other journalists described Sandza as a “writer who snitched”, as below. Also I just love “vengeful byte”, what great wording.

‘

Writer who snitched feels vengeful byte of hackers‘, Associated Press, Orlando Sentinel, Wednesday, December 5th, 1984

Cleveland area hacker King Blotto, as the apparent originator of the very concept of teletrials, was ironically Richard Sandza’s defender in the trial. I have to wonder if the fact that Sandza was very complimentary of Blotto in his original article had something to do with that. Sandza had spoken in glowing terms of “this teenager’s security” which was “as they say, awesome” and noted that “professional computer-security experts could learn something from this kid”.

Modesto Bee, December 11th, 1984

A hacker called Ax Murderer was the presiding teletrial judge on Dragonfire, with another hacker known as Unknown Warrior as the prosecutor.

King Blotto eventually put his finger on the scales of digital justice, or as Sandza put it, “King Blotto has taken up my defense, using hacker power to make his first pleading: he dialed up Dragonfire, broke into its operating system and “crashed” the bulletin board, destroying all of its messages naming me.” However he noted that “the board is back up now, with a retrial in full swing. But then, exile from the electronic underground looks better all the time.“

By December 11th Steve Wilstein, reporting for the Associated Press, was writing the headline ”Teletrial’ clears Newsweek writer’ and that the “beleaguered Newsweek reporter” had “announced with relief” that he had been informed by King Blotto that he had been acquitted on the Dragonfire BBS but that “his telephone and credit card accounts are still under attack”.

Aftermath

‘

Aid for hackers‘, AP, The News Tribune, 28th November, 1985

Richard Sandza had his credit cards reissued with new numbers, had to contact the TRW credit agency and Lenox (Mass.) Savings Bank, a bank that had had their TRW account compromised which had then been used to grab his credit records. In the Washington Post Sandza says that he was not interested in trying to pursue charges against any of the hackers who victimised him, but that he felt “one of my biggest problems is where do I stop being a reporter and when do I start being a cop?”

“Last week, I got a call from a bank that issued my VISA Card and they told me there had been an attempt to charge. $1,100 from it,” he said. “They were unsure whether it had gone through.

“I honestly don’t know if this thing is going to die out,” he said. “I don’t know whether people out there are satisfied or whether someone feels he should get me. I do know that if I plug the phone in, it’ll ring.”

‘‘Teletrial’ clears Newsweek writer‘, Steve Wilstein – AP, Modesto Bee, December 11th, 1984

The whole saga of Richard Sandza and the hackers from beginning to end got a lot of prominent coverage in newspapers across the US. Other journalists definitely paid attention to the fate of their fellow reporter who found himself put on trial by teenage hackers, and the resulting mayhem in his life.

As well as drawing attention to hacker BBSes, hackers themselves and the world they inhabited the revenge campaign against Sandza for revealing hacker secrets ironically caused more secrets to make the national newspapers.

TRW access, access to credit agency systems that can be used to retrieve sensitive financial records, credit card numbers, home addresses, and Social Security numbers relating to an individual, was apparently fairly commonplace among hackers who wanted to get it. Sandza himself, after having his records rifled through, said he was offered TRW access by friendly hackers he discussed the system with.

‘

Hackers can easily get credit information‘, Rita Beamish – Associated Press, Lawrence Journal-World, 9th December, 1984

Information on more than 120 million consumers in the nation’s largest credit information storage system is readily available to computer pirates who pilfer access codes from its users, a spokeswoman for the credit company says.

So-called hackers invade TRW’s vast computerized credit library using codes stolen from the banks, stores or finance companies who are its customers, said Delia Fernandez, spokeswoman for the TRW’s information services division.

Most recently, Newsweek reporter Richard Sandza complained that hackers, apparently upset over an expose he wrote about their activities, entered the TRW system and got his VISA card number.

‘Hackers can easily get credit information‘, Rita Beamish – Associated Press, Lawrence Journal-World, 9th December, 1984

Although Sandza’s case highlighted the issue of hackers gaining access to credit agencies for fraud and doxing people this sort of issue continues to this day and hackers still buy and trade access to large equivalent databases.

‘

Woodhead: Kids Give ‘Hackers’ Bad Name’, The Journal, 5 December 1984

Some tech people of 1984 also waded in to comment on the harassment of Sandza, in The Journal on 5th of December 1984 (‘Woodhead: Kids Give ‘Hackers’ Bad Name’), Robert Woodhead, co-creator of a best selling computer game called Wizardry, labelled the hackers “misguided or evil kids” who were giving legitimate “hackers” a bad name.

Wizardry

Robert Woodhead went on to say “they’re really not ‘hackers,”” and that “we refer to them as ‘crackers’.”

“They’re really not all that skilled,” Woodhead went on to say. “Most really good hackers are sufficiently skilled that they wouldn’t be caught. People like this give the rest of us a bad name.”

In the programming business, Woodhead says, the crackers’ have made themselves an expensive nuisance by trading information on how to illegally enter privately owned computer systems in colleges, businesses and government agencies.

‘Woodhead: Kids Give ‘Hackers’ Bad Name’, The Journal, 5 December 1984

“It’s the dark side of computing,” Woodhead was quoted as saying, “It’s like dynamite. It’s very powerful, when it’s used correctly it can do a lot of good, but in the wrong hands, it can hurt a lot of people.”

‘

Revenge of the computer whiz kids‘, Max Miller, The Sacramento Bee, December 5th, 1984

For his part Sandza was surprisingly philosophical about everything other than the credit agency data leak and the credit card fraud. Sandza described the constant prank phone calls as was “sort of a game. They were calling me up, I was talking to some and hanging up on others”.

About a year after the fallout from his Newsweek articles died down Richard Sandza was still fairly magnanimous when discussing hackers, all things considered. In December of 1985 he spoke with researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories and said of teenage hackers that “if we put all those brains in jail, that’s not going to solve any problems” and urged scientists to “adopt” them and give them a legitimate outlet to satisfy their curiosity about computers.

Richard Sandza interview on hackers, CBS News, August 1985

I contacted Richard Sandza via email to ask if he wanted to add anything to this blog but never got a response, this to me is still one of the most fascinating stories about hackers and reporters in hacking history.

https://realhackhistory.org/2024/01/06/singed-by-dragonfire-newsweek-writer-richard-sandzas-hacker-bbs-teletrial-hackers-reporters/

#1980s #1984 #1985 #2600 #AssociatedPress #BBS #Blottoland #CaptainZap #computer #DragonFire #Dragonfire #ForbiddenZone #hacked #hacker #hackers #hacking #history #journalism #journalist #journalists #KingBlotto #Newsweek #Plovernet #RancidGrapefruit #reporter #reporters #RichardSandza #Shadowland #teleTrial #teletrial #TheVault #WashingtonPost