The thread about Causewayside School, the epicentre of a very Edinburgh and very sectarian Southside scandal

Preamble. The schools of the “School Board” era of public education (1872-1918) have for some reason a particular fascination for me, one which is more profound where they are either no longer in use as schools or have disappeared entirely. This thread began as a couple of lines for my own notes about each of the “Lost Board Schools of Edinburgh” but rapidly snowballed into an intention to cover each, in alphabetical order, on its own and in rather more detail, but not so much that they can’t be posted quite frequently.

The fourth chapter of our series looking at the “Lost Board Schools of Edinburgh” investigates Causewayside School. In 1875 Edinburgh School Board purchased the house of Grange Villa at 140 Causewayside for £3,218 13s 11d with the intention of erecting a new school. This half acre plot was a parallelogram in shape on account of its northern boundary being defined by an old drainage ditch that cut diagonally relative to the main road. Prior to this, schooling in the district was conducted at a school run by the United Presbyterian Church on Duncan Street, which moved with that church to the corner of Salisbury Place in 1864.

An overlay of the 1876 Ordnance Survey town plan of Edinburgh (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

) and modern Google Earth aerial imagery showing the location of Causewayside School. Note the parallelogram shape of the building plot. The UP Church can be seen to the top of the map, its school building to the rear being marked as a Sunday School. Move the slider to compare

The Board had already held a competition in 1874 to find architects for its first batch of new schools and divided the work between the most successful applicants. Causewayside was awarded to Robert Rowand Anderson, who would rise to become one of Victorian Scotland’s most notable architects. He was also awarded the work for schools at West Fountainbridge and Stockbridge and the three shared a number of design and style features (“the dimensions of the various rooms repeat to within a few inches… and the ventilating and playground arrangements are also precisely similar“) but with significant variation in the layouts to make use of three very different sites, all of which had significant constraints.

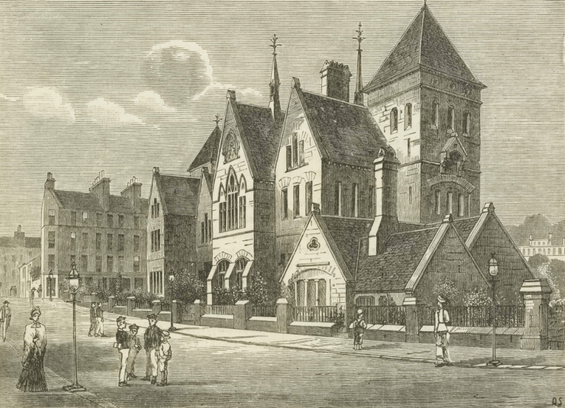

Front elevation by Robert Rowand Anderson of the Causewayside School, dated 1875. University of Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections, Coll-31/2/EC.74

Anderson set Causewayside back from the main road and spread it across two storeys, each with a large central school room with two smaller classrooms on either side at the rear, giving a roughly cruciform footprint. There was a single large gable projecting forwards whereas at Stockbridge (below) there was one on each flank. His early work designing churches translated easily to the Collegiate Gothic style much in favour at the time for schools except now the “steeples” did not contain bells, but hid an Archimedes screw ventilator to promote good air circulation through the buildings.

Stockbridge Primary School by Robert Rowand Anderson, sharing many design features with Causewayside. CC-by-SA 4.0, Drnoble via Wikimedia

The construction contract was worth £7,974 11s 0d and work commenced in late June 1875. Progress by January 1876 was reported as “slow” but by June was “well advanced“. Although it was to be completed for 1st December that year opening did not happen until 9th January 1877. The chairman of the School Board, Professor Calderwood, performed the honours and at this time already 500 of its 600 spaces had been subscribed to.

Rear (left) and north side (right) elevations of Causewayside School, dated 1875. The pair of blocks to the back housed stairs, toilets and offices on intermediate floors, hence the extra sets of windows. University of Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections, Coll-31/2/EC.74

An inspection in its second year of operation reported favourably on the quality of teaching at the school:

Report of HM Inspectors on the Edinburgh Board Schools for Session 1878-79.

Causewayside School.

Mixed School. — An extremely good tone pervaded this School, and the class movements were very orderly. As regards the work of the three lower Standards, some weakness appeared in the spelling and intelligence of the third Standard, but everything else was most satisfactory. Of the upper Standards, the fourth might have done rather better in arithmetic, and the fifth in composition, while both the fifth and sixth Standards answered unequally in history and geography. On the other hand, for grammar, general intelligence, and acquaintance with their specific subjects, all three Standards deserve praise. In judging of the School, it must, of course, be remembered that the staff is strong. Needlework and music are both carefully taught.

Infants’ School. — Discipline and instruction in this Department both deserve the highest praise. It is evident that the Mistress and her Staff exercise a most beneficial influence alike in quickening the intelligence and in regulating the behaviour of their young pupils.

A subsequent inspection in February 1885 by the local Superintendent, Colonel Campbell, “complained strongly” about the drawing examination at the school; the children were using their pencils as a measuring gauge when doing freehand work and that they were placing lined pages beneath their drawing paper as a further guide. The teacher protested that this was how she had been taught to draw but the Colonel demanded that the exam be cancelled: the matter was not dropped until representations in defence from both the Headmaster and Flora Stevenson of the School Board.

Flora Stevenson, a redoubtable figure on the Edinburgh School Board and in the Suffrage movement. 1895 photograph by G. Watson, from the Edinburgh & Scottish Collection of Edinburgh City Libraries.

In common with the first wave of schools that the Board built, Causewayside was really too small to cope with demand and already by October 1878 it was over capacity, with 638 pupils. By 1883 it was so oversubscribed that an extension for 200 further children was authorised, widening the front of the building to the same width as the rear to add additional classrooms. In 1894 a further extension was approved but by the following year there were 250 vacant spaces on account of the recent opening in the district of Sciennes School. By 1901 the school was once again reported to be suffering form overcrowding – this was still a time of urban population growth.

1893 Ordnance Survey town plan centred on Causewayside School, with the original footprint (orange) drawn over the extended footprint which added additional classrooms either side at the front. The wall across the playground was to separate girls from boys, the structures with dotted outlines on the left (west) side being open play sheds. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Located as it was between the Grange and Newington, you could be forgiven for thinking this school as being in a middle-class catchment. However, like most Board schools at this time, it drew its intake largely from the working classes and its pupils were subject to a life in the harsh social environment of Edinburgh at this time. In a court case in February 1884 Helen Dick, or Taylor, was brought before Sheriff Rutherfurd and charged with “failing to provide elementary education for her children and also with failing to secure their regular attendance at school“. She told the court that “she could not do more than she had done” for her two children – Jessie (10) and George (8) – her husband had abandoned the family 6 years prior and to support them she worked anti-social hours at a laundry. She had to leave early in the morning and was not allowed to return home to wake her children and get them ready for school, so they inevitably did not go. The Sheriff ordered that they be made to go to school at Causewayside. Another example comes from an 1896 meeting of the School Board which heard that of the 722 children at the school only 21 had baths in their homes. 71 boys and six girls reported that they went – occasionally – to the Corporation baths to wash. In 1901, it was estimated in 1901 that 15 percent of the juvenile department of the school were working after their school day to help support their families.

Causewayside children, 1927, at Grange Court. The tall building with the Gothic window in the background is the UP Church where the Causewayside School was located prior to the opening of the Board school. Photograph by John Smith, via Edinburgh City Libraries.

In 1905 the headmaster, Robert Mathewson, retired owing to ill health after 20 years in service. He was briefly replaced by James Clark, promoted from St Leonard’s School, who soon returned to the latter institution as its head to be replaced in turn by Thomas W. Paterson of North Canongate. Paterson had begun his career in 1879 at Causewayside and remained there until retiring in 1922 after 51 years in the profession, the pupils and parents presenting him with the gift of a typewriter for the occasion.

On October 1st 1913, pupils from Causewayside joined their compatriots from Davie Street, St Leonard’s and South Bridge in a spontaneous protest march through the district, a rumour having spread through the streets that they were to begin attending school on Saturday Mornings.

Evening schooling began at Causewayside only a month after it opened, when the Edinburgh School of Cookery was allowed by the School Board to run courses here which were open to the general public. This became known as Continuation Schooling; continuation of education for those who had left school (at 14) but had not qualified for a Higher Grade school (or could not afford to go to one). Causewayside became the principal such school for young women and girls in the city, offering both basic academic subjects and practical classes focussing on employable skills – cookery, millinery, laundrywork, dressmaking and needlework. While these classes were not free, in 1915 a term cost 5 shillings, an excellent attendance record could result in the fees being reimbursed. Completion of these classes could qualify women for the Edinburgh School of Cookery and Domestic Economy, where employers provided bursaries. In 1915, 177 pupils earned the return of their fees and forty qualified for the School of Cookery. Headmaster Paterson of Causewayside wrote to the editor of the Scotsman in 1917 that continuation classes were “to the better equipment for life’s battle for those children who leave school at 14 years of age without passing the qualifying examination.”

Advert for Edinburgh School Board’s Continuation Classes, including Causewayside, Musselburgh News, 21st September 1906

An almighty brouhaha erupted at Causewayside in 1925 when the Education Authority announced plans to close the school, transfer its pupils to other nearby schools, and re-open it as a Roman Catholic school. The background is complex but stemmed from the fact that R. C. schooling in Scotland was not transferred from that church to the state until 1918 at which point the newly formed Education Authorities inherited a rather poor portfolio of school premises. Few, if any, of these had been purpose-built and almost none were really fit for purpose; St. Columba’s R. C. School, which served the Southside, was teaching 291 children (with a waiting list of 27) in a totally inadequate converted town house at 81 Newington Road. Causewayside’s school roll had slumped after WW1 due to urban depopulation and with only 321 children was at under half its capacity. The authorities bean-counters were convinced that Sciennes, Preston Street and Bristo schools could comfortably accommodate them, as they too had falling rolls and that nobody would have a problem with them making the most economical use of their buildings.

81 Newington Road, former St Columba’s R. C. School.

How wrong they were! Edinburgh, in case you didn’t know, was a hot-bed of radical, anti-Catholic political Protestantism in the first half of the 20th century and the nascent Scottish Protestant League, led by the rabble-rouser Alexander Ratcliffe, went all in on trying to use the school proposal as a wedge issue in their efforts to repeal the provisions of the Education (Scotland) Act 1918 that saw the state obliged to provide non-secular R. C. schooling. You can read the full details of the vitriolic campaign that they orchestrated to oppose this change in the thread about the Sciennes School Strike of 1925. Suffice to say, the Education Authority was unmoved by the accusations it was handing over a “Protestant school to the Roman Catholics” and “putting Rome on the Rates” in “the city of Knox“. It maintained its position that it had a legal obligation to meet and that its only other option was to build a new school in its entirety – which would add even further to the tax burden of the local rates! And so it was that Causewayside School closed at the end of the 1923-24 term and re-opened after the summer holidays as St Columba’s R. C. The Continuation School was unaffected by all this, a matter quietly and conveniently overlooked by those claiming the school was being “given” to the Catholic Church!

Pupils – and teacher Nun – of St. Columba’s R. C. School in 1925, the year after they moved – controversially – to Causewayside

The Scottish Protestant League were still publicly and vocally agitating against St Columba’s, well into 1925 – until the focus of their ire was drawn to the opening of a Carmelite Convent in Merchiston in September. St. Columba’s closed around 1940, most probably on account of wartime depopulation as a result of evacuation, and was converted into an emergency cooking centre by John Kelly & Son (Kitchen Engineers) Ltd of Rose Street. What became “the largest kitchen in Edinburgh“, capable of cooking 10,000 meals at a time, was intended to help feed the populace in the event of a catastrophic air raid. Fortunately it was never required for this purpose and so was transferred to the Education Committee in 1942 as a central kitchen for producing school meals. Together with the existing centre at the former West Fountainbridge School, together they could produce 9,000 two course lunches daily, sufficient for every child in the city who wanted one. Its official opening took place on Friday 11th September, when Thomas Johnston MP, Secretary of State for Scotland, made a speech imploring the nation to double its consumption of home-grown oatmeal and potatoes. He also announced that school cookery classes would now focus on these ingredients and local and national schools competitions for their use.

Thomas Johnston in 1955 when chairman of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board, by Sir Herbert James Gunn. © artist’s estate, via National Galleries Scotland.

Closure of the Causewayside centre was proposed in 1952, both as an economy measure and also reflecting the fact that most schools now had their own kitchen facilities. Newspaper adverts from 1955 record the disposal of its cooking equipment to the highest bidders.

Adverts for staff at the Causewayside Cooking Centre. Edinburgh Evening News, 25th May 1943

After this it lay vacant for a decade until in 1965 the newly formed Scottish Certificate of Education Examination Board (SCEEB) acquired and demolished it as a location for its new headquarters. A modern, three storey, brutalist office block by Alan Reiach & Eric Hall was built in its place, the only notable feature of an otherwise unremarkable building being an abstract concrete panel over the entrance by Charles Anderson. This includes the crest of the Board and their motto In Trutina Ponentur Eadem which, according to the Dictionary of Foreign Quotations, translates from Latin as “These Matters are to be Weighed in the Balance“. The SCEEB moved in during 1967 but lasted less than a decade, moving in 1975 to Dalkeith on account of needing more space. They were replaced in turn by the Scottish Law Commission but their coat of arms remained, the motto perhaps equally appropriate for both institutions.

Anderson’s relief above the entrance to the SCEEB building

No trace of the old school was and as of the time of writing (September 2025), the redevelopment in turn has been empty for a number of years and a full planning application for its demolition and replacement has been submitted to the Council. A previous plan for the site in 2023 was asked to consider the re-use of the sculptured panel but I understand that the spiritual successor of the SCEEB at Dalkeith are also interested in acquiring it.

The previous chapter of this series looked at Castlehill School. The next chapter examines the Davie Street Schools.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#AlexanderRatcliffe #Brutalism #Catholic #Causewayside #EdinburghSchoolBoard #Education #Food #LostBoardSchoolsOfEdinburgh #School #Schools #ScottishProtestantLeague #Southside