Let's go #Cryptid crazy!! Check out my huge selection of cryptid artwork, featuring all your favorite creepy beasties on personally signed 11x17" prints! All available now at shawnlangley.myshopify.com .

Find art of #mothman, #bigfoot, #chupacabra, #flatwoodsmonster, the #hodag, #fresnonightcrawler, #skinwalker and MORE! Some even in 3D!

This particular piece might still be my favorite Mothman illustration I've ever done, originally created using Pentel brush pens, Copic markers & Posca pens.

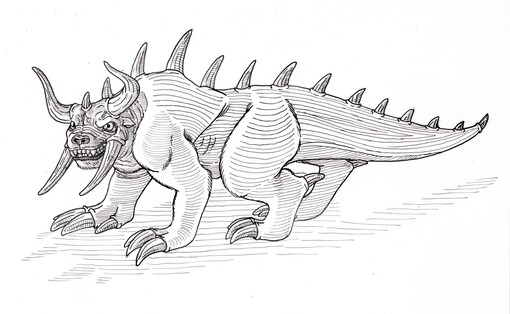

#hodag

Let's go #Cryptid crazy!! Check out my huge selection of #cryptid artwork, featuring all your favorite creepy beasties on personally signed 11x17" prints! All available now at shawnlangley.myshopify.com

Find art of #mothman, #bigfoot, #chupacabra, #flatwoodsmonster, the #hodag, #fresnonightcrawler, #skinwalker and MORE! Some even in 3D!

Fearsome cryptid creatures

In the era of reality TV and social media, the 21st-century version of cryptids evolved rapidly, fueled by a society-wide search for fun weird stuff, enchantment, and a connection to something bigger than oneself. “Cryptids” generally became more well-known and popular. They were readily fictionalized, exaggerated, and artistically distributed worldwide, beyond their original scope. The loosely defined concept of the cryptid as an unknown animal to be discovered (to replace “monster”, as coined in 1983) broadened in popular culture to include all kinds of mysterious creatures. While this expansion created consternation for the old school cryptozoology scene (and does TO THIS DAY for prickly Redditors), it is what it is. Language evolves. Time and context changes our views about mysterious creatures.

The “sharp line” fallacy of cryptids

Contrary to several outspoken cryptozoologists, there is no “sharp line” between mythical creatures, fantastical beasts, folklore creatures, and modern cryptids. They blend into one another through time and across the globe. At one time, even to today, some folks believed that various fantastical creatures, like unicorns, mermaids and dragons, are real animals that did once or still do exist. If witnesses say they see them, aren’t they potential “cryptids” (as ‘ethnoknown’ creatures)? If the cryptozoologist argues that they don’t represent real animals, how do they know? What if a real animal was the basis for the tale? The definitions in cryptozoology are “squishy” and imprecise for many reasons. The “sharp line” defining proper cryptids is a fallacy.

There are the critters that are very obviously supernatural or fiction: most cultures have legends of the undead, shapeshifters, spirit creatures, giants, or witches. We also have tall tales and stories that are meant to serve a social purpose, where the story about someone encountering strange things are held as “true” usually for a brief time (as a child, on a dark night, or as a warning or joke) before we recognize them as fiction. Here’s where we come to Fearsome Creatures.

William Cox’s Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods (1910) is a collection of tales told by lumber workers or hunter-trappers in the northern woods (“with a few desert and mountain beasts”) of the US and Canada. In the same vein, Henry Tryon’s Fearsome Critters (1939) has some overlap with Cox’s but includes a few new entries. These volumes gave us the Hodag, Squonk, Snallygaster, Slide-Rock Bolter, Hidebehind, Wampus Cat, Hoop Snake, and many more outrageous creations meant to be viewed as entertainment, not real beings.

From Cox’s Fearsome CreaturesIf we go by Wall’s proposed definition of cryptid of 1983, which was “a living thing having the quality of being hidden or unknown” – then Fearsome Creatures qualify. (In order to have an operational definition that everyone can clearly understand and follow, you had better be precise, or else.)

Thanks to the re-popularization of Fearsome Creatures/Critters in the Internet/Pop Cryptid age, you will find people saying that one of these is their “favorite cryptid”. The line has been crossed. There is no going back.

Proponents of zoo-cryptids (i.e., belief that the cryptid represents a real, undiscovered animal) reject (most) fearsome or mythological creature tales for obvious reasons – they do not represent real animals. However, this relies on the “sharp line” fallacy mentioned above. If a “cryptid” is believed by some people to be real but rejected by most others, how many people need to believe it real before we count it? Who is the judge?

Zoo-cryptids vs fearsome creatures

Ok, I hear you argue that everyone knows Fearsome Creatures were not intended to be taken as factual. Fair enough. But cultural interpretations are complex things. There are countless native stories of spirit creatures, like Japanese Yokai and Oni, and religious-based beings (angels, demons, etc.), that are respected as culturally “real” and valuable. Some people see hairy wildmen (like Bigfoot) and lake monsters this way, while others accept them as genuine hidden animals. The interpretation is subjective and variable. Part of the goal for early cryptozoologists was to demythify the tales of mystery creatures for zoological sake (zoo-cryptids). By in the 2000s, however, the myths clearly became more important than the zoology in mainstream culture. We now have para-cryptids (that have predominantly paranormal characteristics, also can be considered “zoo-form phenomena” if they appear superficially as animals), and folklore-cryptids (based on myths or folklore, like black dogs, unicorns, mermaids and fearsome creatures).

If we consider all the sub-categories of cryptids, this would allow for unrestricted study into the entire history of each creature, fiction and nonfiction, which is important for understanding. Maybe they represent real animals, spiritual beliefs, cultural fears, or all of them together. Those who are well-versed in cryptozoology should consider how indigenous lore about Cannibal giants, water cats, and little people have been used to justify the possibility of real cryptids. Are the antecedents of today’s purported zoo-cryptids cryptids themselves? It’s complex. Recognizing that complexity opens up new areas of research and understanding.

A modern bestiary

The presentation of Fearsome Creatures is not far removed from what was in the medieval bestiaries. These collections of marvelous creatures were popular in the 14th to 16th century, when we had little credible knowledge of what existed in other lands. The creatures described were absurd. We know that now – but to one who is ignorant of the natural world, how would they have known? Honestly, we see stunning levels of ignorance of nature now. People are prone to believe outrageous things.

Alexander encounters the headless people (Blemmyes), 1445. By Master of Lord Hoo’s Book of Hours – Royal MS 15 E VI, Public DomainAudiences have loved accounts of the strange throughout history. Marvelous creatures were part of the storytelling and art in each time period, often including humor along with reverence, and maybe an underlying ethical lesson or warning.

The proliferation of cryptid tales, and the resurgence of old ones back into the mainstream are evidence that we adore these creature tales and don’t care if they are real or not – it’s fun to just imagine.

Accepting fearsome creatures as cryptids

I’ve been following the growth of cryptid town festivals for several years now. In many instances, the creatures that are celebrated as the mascot or icon is not considered a legitimately real creature, but is still respected as a story that embodies the town history, even if often not in the most respectable light. Here are some infamous examples:

Hodag – Rhinelander, Wisconsin’s infamous legend is commemorated by a statue at the Chamber of Commerce. It’s been the official town mascot since 1918. Modernly depicted as a stocky, aggressive, green-black, feline-frog-dinosaur mash-up with red eyes, huge claws, a spiny-ridged back, and fearsome saber-teeth, the Hodag’s origin is obscure. But it was part of Cox’s original Fearsome Creatures book. The Hodag legend was reimagined, and solidified, by storyteller and jokester Gene Shepard in the closing decade of the 1800s. Shepard brought various bits together from tall tales and Ojibwa legends, and, using wood, ox hide, and some accomplices, created a wondrous hoax. Everyone played along. It has its own town festival, but the Hodag traveling store can be found as a vendor at other cryptid town festivals. For more, see Wisconsin’s Homegrown and Beloved Monster.

Squonk – It’s the hideous Pennsylvania critter that is so ugly, it disintegrates into a puddle of its own tears. The Squonk was in both Cox’s and Tryon’s books. This ridiculous tale is so popular, the Squonk has its own Squonkapalooza in Johnstown, PA – a town which, like Point Pleasant, had its share of disasters. You can find the squonk regularly labeled as a “favorite cryptid” by many who take pity on its dreadful existence.

Snallygaster – A creature from Maryland described as a one-eyed flying reptile with both a beak and teeth, as well as face tentacles, it rocketed to popularity in association with the Jersey Devil appearances in 1909. Some colorful local characters reported that the creature was back on the hunt. The local newspaper played along, warning that it might swoop down to carry off its victims, usually children, and drain their blood. The accepted origin story is that the creature derived from tales from German immigrants to South Mountain, around Frederick, MD. This creature, also from Cox’s tales, has a scandalous history featuring political slanders and violent racism. Yet, it’s got a museum, and is considered a cryptid favorite lately. For more, see this Pop Cryptid Spectator piece.

The SnallygasterConclusion

If someone says a fantastic creature is a cryptid, we can’t stop them. It is not possible to gatekeep popular language. There are many reasons why the term cryptid no longer applies in a narrow zoo-cryptid sense.

I’m inclined to accept an umbrella term of cryptids as encompassing zoo-cryptids, para-cryptids, and fearsome, folklore, fantastical and legendary creatures. In other words, to include anything people claim exists that isn’t officially recognized as genuine. As I explained, it’s too difficult to draw the line about what isn’t and isn’t a cryptid because people say they see or believe in all sorts of weird creatures for all kinds of reasons. Cryptids can be really weird, no one is suitable to judge what is too weird. I don’t, however, accept that the cryptid label is useful to describe mystery animals with the end goal of scientifically identifying them because you cannot know what they are until you find them.

The point I’m trying to make with the controversial inclusion of Fearsome Creatures in a cryptid framing is to recognize the importance of imagination, creativity, changeability, and ultimate cultural value of mysterious creatures (no matter what the explanation is). Technically, with none of the established/infamous cryptids discovered and “realized” in the 21st century, cryptids ONLY value has been cultural – in our stories, our art, as local symbols, commercial icons, or as social themes. In the cultural framing, the impact has been huge. We have a lot to gain to accept and study all cryptids, no matter your definition, in a cultural frame. No one is preventing research and opinions on how these creatures translate to zoological interests, or historic, or social, or psychological, etc. And it’s fine to keep referring to Fearsome Creatures as tall tales. The cultural evolution, and their increasing popularity, is out of our control.

This is part 9 of the 12 Days of Cryptids.

#12DaysOfCryptids #cryptids #fearsomeCreatures #fearsomeCritters #Hodag #snallygaster #Squonk #tallTales

Tiptoeing thru the land of Hodags, oh my!

We were extra careful while passing through the great Northwoods of Wisconsin. Every move we made and every step we took was with extra caution. We wanted to be sure to maintain a respectful low profile.

Why, you may ask? Well…this scenic region is the homeland of Hodags and you do not want to mess with them.

A HodagThe West Coast may have Bigfoot, Scotland the Loch Ness Monster, and Northern Michigan the Dogman, but none can match the legend of the Hodag!

Rhinelander, Wisconsin is the epicenter of Hodag country…even naming their high school team mascot after Hodags to garner more respect by the creatures, as well as fear from their school’s opponents. Likewise, the Hodag is the official mascot of the city. Good and prudent move, Rhinelander!

As can be seen in these accompanying photos, Hodags are creatures not to be taken lightly. As a wary and prudent precaution, the good citizens of Northern Wisconsin always pay respectful homage to the Hodags in order to maintain the peace and tranquility of the region.

So, as visitors to the area, the last thing we wanted to do is upset this delicate equilibrium and bother the local Hodag population. Who knows what kind of calamities might occur!!!

Next time you are in the Northwoods of Wisconsin, be sure to always show proper and due respect to the Hodags. Otherwise, you may become their latest guest for supper…as the main course.

Peace and beware!

#creatures #culture #Folklore #fun #history #Hodag #Hodags #Monsters #mythology #Northwoods #Rhinelander #tourism #travel #Wisconsin

The Hodag, a mythical creature from northern Wisconsin, has influenced local culture for over a century. Originating from logging camp folklore, it reflects regional anxieties and ties to the past. #hodag #cryptids https://connectparanormal.net/2025/04/11/the-hodag-wisconsins-legendary-forest-creature/

The premise of Pop Goes the Cryptid is that the view of doubtful animals (cryptids) has shifted from being a potentially scientific effort of zoological discovery called “cryptozoology” to that of being a media-driven, cultural and commercialized pop culture phenomenon. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t still efforts to find hidden mystery creatures but, more often, the cryptid has a more “folk” importance. An excellent example of a pop cryptid, and one that is currently exploding in popularity, is the Hodag, the mascot of Rhinelander, Wisconsin.

Modernly depicted as a stocky, aggressive, green-black, feline-frog-dinosaur mash-up with red eyes, huge claws, a spiny-ridged back, and fearsome saber-teeth, the Hodag’s origin is obscure. Existing historically, and orally, as a tale of lumberjack folklore in the northwoods, the Hodag legend was reimagined, and solidified, by storyteller and jokester Gene Shepard in the closing decade of the 1800s. Shepard brought various pieces together from tall tales and Ojibwa legends, and, using wood, ox hide, and some accomplices, created a wondrous piece of fakelore.

The ancestor of the Hodag is considered to be Mishipeshu, the spirit creature of the native tribes of the Great Lakes area and northwoods. This “great lynx” was depicted as powerful, and dangerous, with a spiky back and tail, and it lived in the deepest parts of lakes and rivers. Mishipeshu is commonly referred to as the water panther. Some historians believe that the mishipeshu figure had a part to play in the Hodag heritage that Shepard (who spoke Ojibwa) used to bring the modern Hodag legend to life.

Mishipeshu pictograph on Agawa Rock at Lake Superior Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada.In William Cox’s Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods (1910) (see the 100th Anniversary hypertext edition), the Hodag’s appearance is ridiculous, giving us ample foundation to conclude this creature was a made-up story from the Wisconsin and Minnesota lumber camps. Cox notes that it was reportedly rhinoceros-like, hairless and intelligent, and that its body color may be plaid, like the lumberjack coat. Its nose has a spade-shaped horn that grows in an outward direction, blocking the creature’s line of vision so that it can only look up. It searches for porcupines in the trees. When it finds one, it digs around the host tree (with its shovel-nose) so that it falls over, dislodging the porcupine, which is then eaten by the Hodag. For the winter, the Hodag covers itself in pine pitch, rolls in the leaves, and stays warm.

Depiction of Hodag by Cox’s illustrator Coert DuBoisOther legends also indicate the Hodag was some 7 feet long and the reincarnated spirit of the study oxen that dragged logs from the forest (and thus “scientifically named Bovine spiritualis). Early tales never indicated it was a genuine zoological animal. However, it’s not inconceivable that its aggressive nature might have been influenced by the wolverine – which was killed off in those parts by around the 1870s.

From Philadelphia Inquirer, 1897While the tale was known prior to 1893, Eugene Shepard, from Rhinelander, crafted the mythical Hodag into a creature for his own greater purposes. He claimed to have found one in 1893 in the swamplands. He wrote for the local newspaper detailing his account and it was a hit.

In 1895, he created a model out of wood and real animal parts, staging a photo with local men playing along to depict its capture. This is the Hodag we know and love.

In 1896, he staged a side-show “display” of the creature for the Oneida fair and then traveled with it. There was no real animal in the display, but that was not the point – it was the great story that people wanted to see and hear. Check out these pieces to learn about Shepard’s creation and how he was like the P.T. Barnum of Rhinelander.

The Hodag: How Fakelore Became Real | Flyover Culture

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zprRsGgLEo

Hodag: The Fearsome Creature Roaming American Wilderness – Real History channel

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LpkMlzJxgfs

The Hodag now had a specific form and was known to be very dangerous and stinky, but it wasn’t only the creature that smelled funny. The newspapers spreading Shepard’s story sometimes led readers outside the Northwoods to believe that outrageous animal tales like this were true. Some people may have thought the Hodag was real. Shepard continued the ruse by leaving his motives unclear. He suggested that he had really found a Hodag but let it go and said it was a hoax in order to protect it.

What a great logo for the local high school team!But for Rhinelander, Wisconsin residents, it was no hoax. It is an important part of their heritage. They adopted the Hodag as the town mascot in 1918. Even though there was a dispute in the town about how much to embrace the “fakelore” Hodag, ultimately, the creature won the hearts of the town. As sometimes happens, the “fakelore” was widely accepted and morphed into real folklore. As UW-Madison folklore professor Lowell Brower noted (in the Flyover Culture video above), the Hodag created by Shepard was “folkloresque” – based on folklore and drew its power from that. Rhinelander “lovingly appropriated and commercialized” the legend. It appears everywhere in the town and draws visitors that would otherwise never look twice at the small town in Northern Wisconsin.

Today’s Hodag is based on Shepard’s tale, not the lumberjack tale memorialized in Cox’s 1910 volume. In some depictions, the Hodag now resembles the original Chupacabra (spiky back, red eyes, sharp teeth and claws, and a lizard tongue). The ambiguity of the hodag invites participation, and people are happy to act out the legend (called “ostention) by pretending it’s real and even hunting for the creature. The fact that the Hodag was a known hoax did not stop people from wanting to see it.

The latest claims to fame for the Hodag is its appearance in a 2012 Scooby-Doo episode, where “Gene Shepard” appears as a showman with a traveling cabinet of curiosities.

The Hodag also has an entry in the Harry Potter universe book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them where their horns were said to have magical properties to keep people awake for days and be unaffected by alcohol.

You can find lots of Hodags in the Hodag store in Rhinelander, where the owner Ben Brunell says the symbol brings the community together. He opened the store because people wanted Hodag souvenirs. A traveling Hodag exhibit appeared at the 2024 Mothman festival and at many other places across the US. And you can stay at the Hodag AirBnB which is also crawling with the creatures. So while the legend of the Hodag is flourishing, a real flesh and blood creature will, by its non-nature, be impossible to find.

Bibliography and More:

- The Rhinelander Visitors Page – https://explorerhinelander.com/

- The Rhinelander Chamber of Commerce – About the Hodag https://www.rhinelanderchamber.com/about-the-hodag/

- Wisconsin Historical Society – The Hodag: Learn the history of the Hodag, Rhinelander’s mystical menace https://wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS16353

- Pioneer Park Historical Complex https://rhinelanderpphc.com/hodags/

https://moderncryptozoology.wordpress.com/2024/10/10/hodag-wisconsins-homegrown-and-beloved-monster/

#cryptid #Cryptozoology #GeneShepard #Hodag #lumberjackTales #mascot #Mishipeshu #monster #Ojibwe #PopCryptid #Rhinelander #tallTales #Wisconsin

Hodag!

"I smell a Hoe Dagg!... gonna track it down"

More than 3 are a "pack of hodags".

Used in a sentence:

"I saw a pack of hodags workin' the corner of Fifth and Lincoln last night."

Pop cryptid chatter: Beards and encryptids

My favorite fringe topic has always been cryptozoology, which is the intersection of animals and mysterious weirdness. As I’ve written about the subject of “pop cryptids”, fabulous monsters are now mainstream. They have become ubiquitous online and in American culture, not so much as possibly real zoological organisms to be scientifically recognized (because none have been) but as symbols, icons, and genii locorum (spirits of a place). It’s my opinion that these current depictions of cryptids are where the fascinating content lies, and that there is little value in considering cryptozoology as a zoological endeavor. The reasoning is complex but that leaves so much left to explore for these cultural concepts. For this post, I’m sharing some pop cryptid related items I found this week.

For more on Pop Cryptids, head to Pop Goes the Cryptid or see other posts here.

Cryptozoologists, represent!

Did you ever notice something in common between featured speakers of cryptid conferences?

What is with the beards?! Yep. Every one of these are guys with beards. (Hats may be an indicator of which of them are less “academic” and more field-oriented.) You may recognize a few of these usual suspects.

It’s all too easy to apply these generalized characteristics to those interested in particular fringe topics. (Maybe it’s just me, because I’m not a beard-fan.) And, I will admit, it’s not totally fair. That is, the audience is more diverse. The photo above was from the 2023 Florida Bigfoot event in which a YouTube video of the vendor room showed, Ok, many more beards, but also many women and some kids. Regardless of the audience, the narrow demographic appearing on the stage representing the leadership in this community is glaring. The invited speakers are not scientists (except for usually one who flashes that label for cred – last year J. Meldrum and this year R. Holland). The story, not the science, is the star. To me, that says something important.

The 2024 event just took place last weekend and not much has changed. The generalization holds.

Additional photos show that the appeal of the idea of Sasquatch, and all the cute and kitschy stuff related to it, is embraced by the younger generation because it’s fun. Not so much because they really think it’s a legit undiscovered animal.

From the NPR affiliate in Florida:

[Organizer] Pippin estimated that more than 2,000 people in total visited the conference, which featured a stage for speakers and about 45 vendors.

Ryan “RPG” Golembeske, 48, served as master of ceremonies.

“You are in the one absolute safe place to go all in on the squatch,” Golembeske said to the crowd. “Everybody here wants to talk about it. Everybody here is obsessed with it.”

I don’t think it’s healthy to be obsessed with an unproven creature. But, that’s a word that’s maybe overused these days. Maybe not.

And cryptid proponents love to tout how youngsters are getting into the cryptozoology act and often give them a platform. However, I’ve seen many such teens grow out of belief in forest monsters as real life dawns on them. Some stay hooked all their lives. Since we have 50+ years of actively looking for Bigfoot and not finding it, this seems like a highly questionable obsession.

The Encryptids

This week saw the Electronic Frontier Foundation launch their membership drive featuring The Encryptids – “the rarely-seen enigmas who inspire campfire lore. But this time, they’re spilling secrets about how they survive this ever-digital world.”

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that cryptid creatures can be creatively used for cryptocurrency and encryption. This promotional material is charming.

Note the appealing “cute” factor – a key to reaching a wide audience. It also appears EFF will be loose with the cryptid label by featuring not just Bigfoot, but a Jackalope and maybe a ghost. I do like it, though. Why not? It’s a good cause.

For your listening pleasure

Besides the Jackalope, a famous manufactured animal of renown is the Hodag, the official mascot of Rhinelander, Wisconsin. I want to recommend the Urban Legends podcast episode on the Hodag written and hosted by Luke Mordue.

Check it out here. And have a listen to the other Modern Myths episodes.

Passing of Richard Ellis

Finally, I was sorry to hear of the passing of Richard Ellis, 86, an author and artist who greatly informed me about marine life. His Monsters and the Sea is one of my top cryptozoology books.

I recommend his NYT obituary and this tribute by Darren Naish on Tet Zoo.

It is a sign of a life well-lived when you leave behind your lauded words, images, and ideas to continue on.

#animals #Bigfoot #cryptids #cryptozoologist #Cryptozoology #encryptids #Hodag #Internet #Monsters #podcast #popCryptids #popularCulture #RichardEllis #Sasquatch

https://sharonahill.com/?p=8596

Location and imagination equals ‘cryptid’

Today, I’m making some general observations on the subject of strange animal sightings. I recently visited Lake Champlain and am convinced that many sightings of Champ, the lake monster, were logs or other mundane objects or animals. There are no cryptids there. But there is a granite marker and a friendly-looking fiberglass Champ depiction at Perkins Pier in Burlington, Vermont. Champ is stylized as a huge dragon-like sea serpent. It’s a mascot of the lake and the local baseball team. I can’t help but love this, while at the same time be frustrated by the remaining trend to suggest Champ is a prehistoric reptile or rare animal. The legend is sustained by the location and people’s sense of imagination.

Champ as the mascot of the Vermont Lake Monsters baseball team, Burlington, VermontStrange animal stories have always had, primarily, a theme of wonder and amazement. Even when the animal is clearly visible, such as with clear videos or carcasses, many spectators opinionate that the creature is a “mutant” or a new species. They don’t recognize the obvious, natural, and better explanations. Or, they refuse to accept them because it is more fun to speculate.

Could our need for fantasy creatures be contributing to cryptozoology failing as a scientific field?

The area of study that was called cryptozoology gained scientific credibility with a society and a journal established in 1982. A group of scientists and people interested in animal research founded the International Society of Cryptozoology. Its mission was to investigate and analyze reports of unexpected animals with the goal of determining if they were new species that could be cataloged and scientifically known.

That didn’t work out well. The society dissolved in 1996 with no clear successes other than to document the optimistic nature of the participants. The scientific credibility declined, but some zoological hope still lingers, as several followers of the field insist that it can be a legitimate means of discovering new animals. The prospects for this goal grow weaker every year. Instead, the popular mythical and romantic view of cryptozoology has swamped the idea of cryptozoology as a scientific endeavor. The cryptid legends seem ever more immune to scientific thinking. The skin and blood of cryptids are made of human imagination and the spirit of place.

The Hodag of Rhinelander, WisconsinIn the 2000s, there was still a strong tone of cryptozoology as a science-based endeavor. But, by then, it was almost entirely the domain of amateurs. Unlike fruitful areas of scientific investigation, the evidence never got better – there were no bodies, no DNA, no tested theories, just better hoaxes and more media circulating with enthusiastic commentary.

There also was more attention to local promotion. Festivals associated with local creatures became popular. Public displays became more prominent. New social media featuring existing legends, and creating entirely new ones, expanded the reach of cryptids to the younger online generation. This promotion, done on TV, YouTube and TikTok was done by non-scientists, even teens who knew little about the origins of cryptozoology.

A Bigfoot mascot in Whitehall, New York (at the Southern reaches of Lake Champlain)Many cryptids are almost always associated with particular locations. The obvious are lake monsters because they are bounded by the water. (Almost every large lake has a story of a monster.) This is reasonable, as the legend is rooted in and grows around a cluster of reports. Land animals are naturally attributed to an area, like a forest or swamp. Here are some examples:

- Dogman – Forests of Wisconsin and Michigan

- Mothman – West Virginia and later Chicago area

- Bigfoot – Typically tied to the PNW but by the 1970s became popular in many states, often referred to by a local name [Beast of Boggy Creek (Arkansas), Momo (Missouri), Skunk Ape (Florida)]. Certain areas were associated with ape-like beings and other paranormal concepts and entities – Chestnut Ridge (Pennsylvania), the Appalachians, and Skinwalker Ranch (Utah).

- Ultra local stories include Loveland Frog, Dover Demon, Beast of Bray Road, Lizard Man of Scape Ore swamp, Goatman.

Of course, there are exceptions:

- Chupacabra – Started as a Hispanic legend and became a catch-all term for any weird animal anywhere.

- Yeti – Began as associated with the Himalayas but became iconic worldwide even though still connected to its origins in cold, mountainous regions.

- Entities that may be considered “fantasy creatures” like merfolk and fairies (and related beings) show up everywhere people have brought their culture and stories with them. The same can be said for Bigfoot (wild man) and lake monsters.

Cryptids tied to locations seems to be a product of the environment + promotion. The legend will often readily morph into a mascot for a town or area. The locals may eventually embrace their monster and make the most of it. The commodification and exploitation of the cryptid aids in the drift away from the prospect of a serious scientific endeavor to find it. It also promotes fakery for attention or fun.

The Comegato

The latest invented cryptid is the Comegato of Maine, a weasel man creature featured in a “documentary” on YouTube. While I’m sticking to the U.S. in this post, see also the British Cryptid (1974) YouTube channel for invented local cryptids.

As the depiction of cryptids turns more towards entertainment and whimsy, the thought of the “-ology” part becomes less emphasized. Many people will admit they don’t want their local creature found or identified. They love the mystery and will actively seek to preserve it. Thus, the cryptids’ value lies not in zoological discovery, but in social needs. The field of cryptozoology may be doomed to further slide towards a fictionalized, pretend idea of science.

There is nothing wrong with celebrating your local legends. I think the depictions of Champ, Bigfoot, the Fresno Nightcrawler, the Hodag, and all the other crazy critters are awesome, and I want to see the statues and swag. Celebrate your local monster for all the human reasons it exists.

#Bigfoot #ChampLakeMonster #Comegato #cryptid #Cryptozoology #Hodag #lakeMonsters #Monsters #Paranormal

https://sharonahill.com/?p=8584

I borrowed https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/59978434-the-united-states-of-cryptids book at the library and have been drawing most (I skip the bigfoots/monkeys/boring ones) of the cryptids as I read.

These are the midwest ones

Cave Hodags - [fearsome critters] - a subterranean variant to the 'Sidehill-Dodge-Hodag' & its evolutionary successor. They have 3 glowing eyes & 5 legs for scaling walls, The Wisconsin Speleological Society has held 'Cave Hodag Hunts' since 1965! - : Full post: https://samkalensky.com/products/cave-hodags

Hoedag - [Fearsome Critter.] - The 'Lake Monster. of St Marys, Ohio.' It has a long neck with an eerie glowing green eye on its forehead, a bright red eye on its tail & round plate-like feet. Said to steal Pumpkin Pies & eat lost little dogs...🚦Full post:

https://samkalensky.com/products/hoedag

#hodag #hoedag #lakestmaries #folklore #fearsomecritter #cryptid #mastoart

In todays full #hodag post I covered a lot of lesser known/talked about hodag variants! ( including one hunted by teddy rosevelt in 1913! ) https://patreon.com/samkalensky

The Hodag. - [Fearsome Critter] - Vicariously described among lumbermen & most famously attributed to Rhinelander Wisconsin. - "Hodags" are usually noted for their ugliness, ferocity & stench. Whenever an Ox is cremated in the woods, a hodag is born... 🍋 Full post: https://samkalensky.com/products/hodag

#cryptids #folklore #rhinelander #hodag #rosevelt #mythology #MastoArt

Whotcher, Hodags!

#Iowa's Whatcheeria deltae sounds suspiciously like #Wisconsin's #Hodag. You never see them in the same place at the same time, right?

My artistic interpretation of the Hodag attached for comparison, along with the W Deltae from

https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article/193/2/700/6144098

https://www.joviko.net/hodag.html

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/whatcheeria-iowa-predator

Whotcher, Hodags!

#Iowa's Whatcheeria deltae sounds suspiciously like #Wisconsin's #Hodag. You never see them in the same place at the same time, right?

My artistic interpretation of the Hodag attached for comparison, along with the W Deltae from

https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article/193/2/700/6144098

https://www.joviko.net/hodag.html

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/whatcheeria-iowa-predator

We believe that investing in people is better than investing in cryptocurrency. Help us make a difference for college-bound high school seniors in Wisconsin’s Northwoods by making your donation to the Clambake Society Scholarship today!

#Hodag from Rhinelander, Wisconsin

Fearsome Crittober Day 4: The Hodag. #hodag #art #fearsomecritters #folklore #americanfolklore #inktober #inktober2018 #creaturedesign #ink #monster

A monstrous creature native to Wisconsin. Covered in green fur, with red eyes, horns, tusks, large claws, and a back covered in spines, the Hodag is about the size of a large dog.

![[Newspaper excerpt of the 'Hoedag' as drawn by "Edward Fusk." - Photo Thanks to the lake improvement association.]](https://files.mastodon.social/cache/media_attachments/files/110/454/496/644/227/278/small/00c2aedb1b636e35.webp)