In a rural health center in Kenya, a community health worker develops an innovative approach to reaching families who have been hesitant about vaccination.

Meanwhile, in a Brazilian city, a nurse has gotten everyone involved – including families and communities – onboard to integrate information about HPV vaccination into cervical cancer screening.

These valuable insights might once have remained isolated, their potential impact limited to their immediate contexts.

But through Teach to Reach – a peer learning platform, network, and community hosted by The Geneva Learning Foundation – these experiences become part of a larger tapestry of knowledge that transforms how health workers learn and adapt their practices worldwide.

Since January 2021, the event series has grown to connect over 21,000 health professionals from more than 70 countries, reaching its tenth edition with 21,398 participants in June 2024.

Scale matters, but this level of engagement begs the question: how and why does it work?

The challenge in global health is not just about what people need to learn – it is about reimagining how learning happens and gets applied in complex, rapidly-changing environments to improve performance, improve health outcomes, and prepare the next generation of leaders.

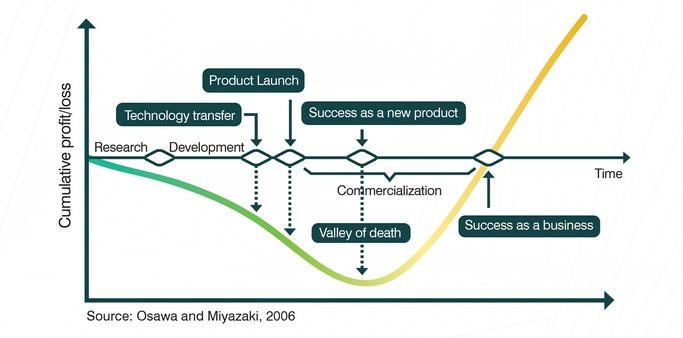

Traditional approaches to professional development, built around expert-led training and top-down knowledge transfer, often fail to create lasting change.

They tend to ignore the rich knowledge that exists in practice – what we know when we are there every day, side-by-side with the community we serve – and the complex ways that learning actually occurs in professional networks and communities.

Teach to Reach is one component in The Geneva Learning Foundation’s emergent model for learning and change.

This article describes the pedagogical patterns that Teach to Reach brings to life.

A new vision for digital-first, networked professional learning

Teach to Reach represents a shift in how we think about professional learning in global health.

Its pedagogical pattern draws from three complementary theoretical frameworks that together create a more complete understanding of how professionals learn and how that learning translates into improved practice.

At its foundation lies Bill Cope’s and Mary Kalantzis’s New Learning framework, which recognizes that knowledge creation in the digital age requires new approaches to learning and assessment.

Teach to Reach then integrates insights from Watkins and Marsick’s research on the strong relationship between learning culture (a measure of the capacity for change) and performance and George Siemens’s learning theory of connectivism to create something syncretic: a learning approach that simultaneously builds individual capability, organizational capacity, and network strength.

Active knowledge making

The prevailing model of professional development often treats learners as empty vessels to be filled with expert knowledge.

Drawing from constructivist learning theory, it positions health workers as knowledge creators rather than passive recipients.

When a community health worker in Kenya shares how they’ve adapted vaccination strategies for remote communities, they are not just describing their work – they’re creating valuable knowledge that others can learn from and adapt.

The role of experts is even more significant in this model: experts become “Guides on the side”, listening to challenges and their contexts to identify what expert knowledge is most likely to be useful to a specific challenge and context.

(This is the oft-neglected “downstream” to the “upstream” work that goes into the creation of global guidelines.)

This principle manifests in how questions are framed.

Instead of asking “What should you do when faced with vaccine hesitancy?” Teach to Reach asks “Tell us about a time when you successfully addressed vaccine hesitancy in your community.” This subtle shift transforms the learning dynamic from theoretical to practical, from passive to active.

Collaborative intelligence

The concept of collaborative intelligence, inspired by social learning theory, recognizes that knowledge in complex fields like global health is distributed across many individuals and contexts.

No single expert or institution holds all the answers.

By creating structures for health workers to share and learn from each other’s experiences, Teach to Reach taps into what cognitive scientists call “distributed cognition” – the idea that knowledge and understanding emerge from networks of people rather than individual minds.

This plays out practically in how experiences are shared and synthesized.

When a nurse in Brazil shares their approach to integrating COVID-19 vaccination with routine immunization, their experience becomes part of a larger tapestry of knowledge that includes perspectives from diverse contexts and roles.

Metacognitive reflection

Metacognition – thinking about thinking – is crucial for professional development, yet it is often overlooked in traditional training.

Teach to Reach deliberately builds in opportunities for metacognitive reflection through its question design and response framework.

When participants share experiences, they are prompted not just to describe what happened, but to analyze why they made certain decisions and what they learned from the experience.

This reflective practice helps health workers develop deeper understanding of their own practice and decision-making processes.

It transforms individual experiences into learning opportunities that benefit both the sharer and the wider community.

Recursive feedback

Learning is not linear – it is a cyclical process of sharing, reflecting, applying, and refining.

Teach to Reach’s model of recursive feedback, inspired by systems thinking, creates multiple opportunities for participants to engage with and build upon each other’s experiences.

This goes beyond communities of practice, because the community component is part of a broader, dynamic and ongoing process.

Executing a complex pedagogical pattern

The pedagogical pattern of Teach to Reach come to life through a carefully designed implementation framework over a six-month period, before, during, and after the live event.

This extended timeframe is not arbitrary – it is based on research showing that sustained engagement over time leads to deeper learning and more lasting change than one-off learning events.

The core of the learning process is the Teach to Reach Questions – weekly prompts that guide participants through progressively more complex reflection and sharing.

These questions are crafted to elicit not just information, but insight and understanding.

They follow a deliberate sequence that moves from description to analysis to reflection to application, mirroring the natural cycle of experiential learning.

Communication as pedagogy

In Teach to Reach, communication is not just about delivering information – it is an integral part of the learning process.

The model uses what scholars call “pedagogical communication” – communication designed specifically to facilitate learning.

This manifests in several ways:

- Personal and warm tone that creates psychological safety for sharing

- Clear calls to action that guide participants through the learning process

- Multiple touchpoints that reinforce learning and maintain engagement

- Progressive engagement that builds complexity gradually

Learning culture and performance

Watkins and Marsick’s work helps us understand why Teach to Reach’s approach is so effective.

Learning culture – the set of organizational values, practices, and systems that support continuous learning – is crucial for translating individual insights into improved organizational performance.

Teach to Reach deliberately builds elements of strong learning cultures into its design.

Furthermore, the Geneva Learning Foundation’s research found that continuous learning is the weakest dimension of learning culture in immunization – and probably global health.

Hence, Teach to Reach itself provides a mechanism to strengthen specifically this dimension.

Take the simple act of asking questions about real work experiences.

This is not just about gathering information – it’s about creating what Watkins and Marsick call “inquiry and dialogue,” a fundamental dimension of learning organizations.

When health workers share their experiences, they are not just describing what happened.

They are engaging in a form of collaborative inquiry that helps everyone involved develop deeper understanding.

Networks of knowledge

George Siemens’s connectivism theory provides another crucial lens for understanding Teach to Reach’s effectiveness.

In today’s world, knowledge is not just what is in our heads – it is distributed across networks of people and resources.

Teach to Reach creates and strengthens these networks through its unique approach to asynchronous peer learning.

The process begins with carefully designed questions that prompt health workers to share specific experiences.

But it does not stop there.

These experiences become nodes in a growing network of knowledge, connected through themes, challenges, and solutions.

When a health worker in India reads about how a colleague in Nigeria addressed a particular challenge, they are not just learning about one solution – they are becoming part of a network that makes everyone’s practice stronger.

From theory to practice

What makes Teach to Reach particularly powerful is how it fuses multiple theories of learning into a practical model that works in real-world conditions.

The model recognizes that learning must be accessible to health workers dealing with limited connectivity, heavy workloads, and diverse linguistic and cultural contexts.

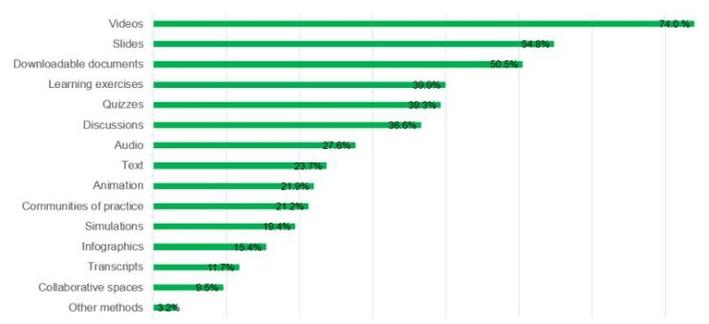

New Learning’s emphasis on multimodal meaning-making supports the use of multiple communication channels ensuring accessibility.

Learning culture principles guide the creation of supportive structures that make continuous learning possible even in challenging conditions.

Connectivist insights inform how knowledge is shared and distributed across the network.

Creating sustainable change

The real test of any learning approach is whether it creates sustainable change in practice.

By simultaneously building individual capability, organizational capacity, and network strength, it creates the conditions for continuous improvement and adaptation.

Health workers do not just learn new approaches – they develop the capacity to learn continuously from their own experience and the experiences of others.

Organizations do not just gain new knowledge – they develop stronger learning cultures that support ongoing innovation.

And the broader health system gains not just a collection of good practices, but a living network of practitioners who continue to learn and adapt together.

Looking forward

As global health challenges have become more complex, the need for more effective approaches to professional learning becomes more urgent.

Teach to Reach’s pedagogical model, grounded in complementary theoretical frameworks and proven in practice, offers valuable insights for anyone interested in creating impactful professional learning experiences.

The model suggests that effective professional learning in complex fields like global health requires more than just good content or engaging delivery.

It requires careful attention to how learning cultures are built, how networks are strengthened, and how individual learning connects to organizational and system performance.

Most importantly, it reminds us that the most powerful learning often happens not through traditional training but through thoughtfully structured opportunities for professionals to learn from and with each other.

In this way, Teach to Reach is a demonstration of what becomes possible when we reimagine how professional learning happens in service of better health outcomes worldwide.

Image: The Geneva Learning Foundation Collection © 2024

Share this:

https://redasadki.me/2024/10/30/what-is-the-pedagogy-of-teach-to-reach/

#continuousLearning #globalHealth #learningCulture #learningStrategy #learningTheory #pedagogicalPatterns #peerLearning #TeachToReach #TheGenevaLearningFoundation