Sometimes what I read tells me what to write about. Other times the hints come from what I watch. This time it’s both. First I read a line in Richard Pryor’s autobiography Pryor Convictions with this mighty stack of intensifying negatives:

You can’t tell nobody not to snort no cocaine.

That led me to rewatch Richard Pryor: Live in Concert, in which the comedian says:

I don’t wanna never see no more police in my life.

That was hint #1, in two parts.

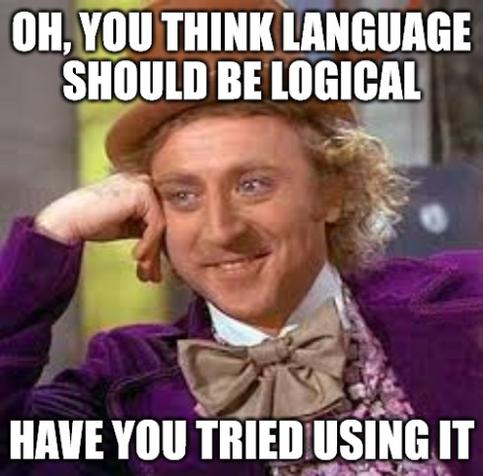

Pryor’s meaning is clear in both cases. But grammar purists still disapprove. Some would even disagree that the meaning is clear, claiming that the first one ‘logically’ means ‘You can tell somebody to snort some cocaine.’

The maths- or logic-based objection to negative concord – better known as the double negative – crops up reliably in these discussions. It can usually be disregarded as bad-faith hyperliteralism or misguided overapplication of formal logic. Either way, it’s flat-out wrong, as we’ll see.

Negative concord has a bad reputation despite centuries of common use in varieties of English around the world. This post looks at why that is, and why it shouldn’t be. It’s a long post, 2,500+ words, because there’s a lot of ground to cover and I want to bring something fresh to readers broadly familiar with the terrain.

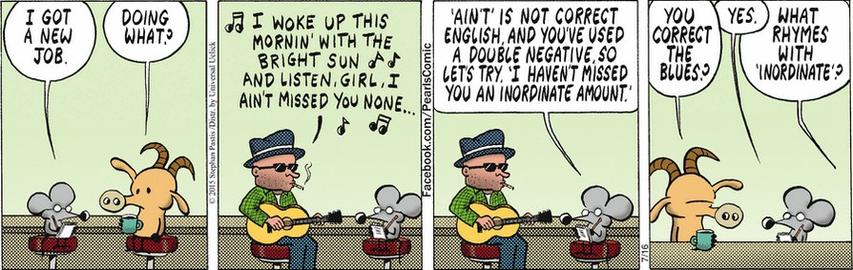

[click images to enlarge]

Pearls Before Swine by Stephan Pastis

Hint #2 was an example of the purist disapproval in the crime film Dragged Across Concrete (2018). Getaway driver Henry, played by Tory Kittles, gets criticized for using a double negative by veteran cop Brett, played by Mel Gibson:

HENRY: You sure you ain’t an elementary teacher, used to dealing with kids who don’t know nothing?

BRETT: I believe what you meant to say was, ‘who don’t know anything’.

HENRY: You understood me, didn’t you?

BRETT: Yeah, but you’re a lot smarter than you sound – a whole lot smarter from what I’ve seen.

HENRY: It’s good to be underestimated.

In another scene, Henry gets ‘corrected’ (by a different white man) for saying ‘We here’. This abridged syntax is an example of zero copula, which, like negative concord, is a feature of Henry’s dialect, some form of African American Vernacular English (AAVE). Henry claps back in both exchanges.

Before delving in, I’ll clarify the terminology. Double negative is the popular term, but it implies just two negatives, whereas there may be three or more, as we’ve seen. Double negative can also refer to litotes, a rhetorical device where two negatives (one of them often a prefix) make a weak positive, as in ‘not untrue’.

Double negative (and multiple negative/negation) can also entail ‘true double negation’, where the negatives obviously cancel out, as in ‘I’m not not saying that’. Litotes and true double negatives are not the issue here, so I mostly use the term negative concord (NC), which, though less familiar, is more accurate and less semantically knotty.

Negative concord today

To get a (very rough) sense of current attitudes to negative concord, I ran a quick poll on Mastodon. The results should be taken with a pinch of salt but are interesting nonetheless:

Two thirds of the 458 people who voted were fine with negative concord, whether they used it or not. Over 30% dislike it: that’s a lot. (And 1% are somehow unaccounted for.)

People who replied were mostly positive or neutral about NC. One was taught – in the 1960s, no less – that NC was appropriate for emphasis. Their enlightened teacher even stressed the important difference between formal written language and informal usage, a distinction lost on many people today.

Others said double negatives are ‘grammatically incorrect’, are ‘sloppy’, and ‘make you sound ignorant’, confirming Elizabeth Grace Winkler’s characterization of NC, in Understanding Language, as ‘one of the most stigmatized features of non-standard varieties of English’ and a sign for some that ‘standards are going down the drain’.

Of course, that’s been happening since forever.

Pedants might joke about Mick Jagger singing that he can get some satisfaction, or Pink Floyd needing some education, but no one seriously thinks this. Yet the same allowances aren’t made for people who use double negatives naturally in their everyday language, as I wrote at Macmillan Dictionary a few years ago.

Negative concord may be associated particularly with certain dialects, like African American Vernacular English, Appalachian English, and Cockney, but it seems to occur wherever English is spoken. So why the reluctance to accept it, given that it’s a normal feature of informal registers in dialects around the world? I look at this below.

NC is also integral to many languages other than English, as seen in Dryer’s World Atlas of Language Structures. (Many languages with negative concord, like French, are excluded from the map because they use negative particles that are optional in colloquial expression.) Linguistically, negative concord is as routine it gets.

History and decline of NC

NC in English is as old as English itself. Old English nan man nyste nan þing (‘no one knew anything’) literally means ‘no man not-knew no thing’.1 Such ‘repetition of uncancelling negatives’, Robert Burchfield writes in his revision of Fowler, was ‘the regular idiom . . . in all dialects’ in Old and Middle English.

Otto Jespersen, in Negation in English and Other Languages, suggests that when negation is weakly marked – by an unstressed particle, for example – there’s a tendency to reinforce it by adding another negative marker, which, in its turn, may gradually lose its negative force. This process came to be called Jespersen’s Cycle.

Here’s a stack of four in Chaucer:

He nevere yet no vileynye ne sayde

In al his lyf unto no maner wight

[He never yet no abuse not said

In all his life to no manner of creature]2

Negative concord began to wane well before Shakespeare’s time, but it was still current enough for the playwright to use at the turn of the 17thC: ‘And that no woman has; nor never none / Shall mistress be of it’ (Twelfth Night); ‘There’s never none of these demure boys / come to any proof’ (Henry IV, Part II).

As the ‘more effusive’ types of multiple negative fell out of literary favour, double types persisted, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage (MWDEU). Here’s one in Robinson Crusoe (1719): ‘I had lost no time, nor abated no diligence’. In some editions this is tellingly revised to ‘. . . any diligence’.

NC declined in part because it was supplanted by competing negative polarity items (like any) which, writes negation specialist Frances Blanchette, were used ‘as a marker of higher social status’. A historical review of negation in English concludes that standardized English lacks NC because of the effects of Middle English and Early Modern English speakers’ choices of ‘prestige forms and the subsequent standardisation of these’.

So these patterns of using either negative concord or its syntactic alternatives became entangled in the gradual codification of standard (or standardized) English.3 This variety of the language is not linguistically superior but has greater social prestige because of historical events centred on power, privilege, chance, and colonialism.

Negative concord is stigmatized today because it’s prohibited in standardized English and associated with people from non-dominant socioeconomic and ethnic populations: working-class people and people of colour.4 And language has always been a convenient proxy for social prejudice. Norman Fairclough, Language and Power:

Standard English was regarded as correct English, and other social dialects were stigmatised not only in terms of correctness but also in terms which indirectly reflected on the lifestyles, morality and so forth of their speakers, the emergent working class of capitalised society: they were vulgar, slovenly, low, barbarous, and so forth. . . . The codification of the standard was a crucial part of this process, which went hand-in-hand with prescription, the designation of the forms of the standard as the only ‘correct’ ones.

Off the Mark by Mark Parisi

The grammarians

The shift away from negative concord was boosted by the efforts of grammarians in the 18thC. These influential educators modelled English on their beloved Latin to make English more ‘proper’.5 This was misguided for several reasons. For one, English is structurally Germanic, not Romance. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Speaking of romance:

One of these grammarians was Robert Lowth, whose Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) said, ‘Two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative’. This rule of Classical Latin grammar does not apply the same way to English and so had to be enforced artificially.

Curiously, the rule did not appear in the first edition of Lowth’s Introduction, as Henry Hitchings reports in The Language Wars:

At the time he was writing, double negation was not common in written English, and it seems likely that Lowth was motivated to condemn it because it was regarded as a mark of poor education or breeding, and was thus the sort of thing his son (and other learners) must avoid. Since he did not mention it in the first edition of the Short Introduction, it seems plausible that double negation was not something he had come across in practice, and that it was brought to his attention by one of his early readers. Alternatively, he may have seen it condemned in another grammar – the most likely being James Greenwood’s An Essay Towards a Practical English Grammar (1711).

A few decades later, Lindley Murray’s phenomenally successful English Grammar (1795), which drew heavily on Lowth’s work, repeated the canard. Others fell in line, and the myth took hold among generations of educators and social climbers. The ‘rule’ calcified into creed, and NC’s status has been unfairly tainted ever since.

Vernacular use

MWDEU describes negative concord’s sphere of use in the 18thC as ‘contracting’ and ‘restricted to familiar use—conversation and letters’. This may belie its prevalence, though, since conversation comprises the great bulk of language, and letters were a hugely popular form of communication until the late 20thC.

Where NC was once the default style of negation even in ‘elevated’ places like literature, after its decline authors began using it as a device to mark rustic or ‘unlettered’ speech:

‘An’ there was niver nobody else gen me nothin’ but what I got by my own sharpness’ (George Eliot, Mill on the Floss, 1860)

‘They ain’t no different way’ (Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, 1876)

‘We don’t want no shoutin’ here’ (Sean O’Casey, The Plough and the Stars, 1926)

They also continued using it in letters and other relatively informal contexts, as MWDEU shows:

I never believe nothing until I got the money (Flannery O’Connor, 1952)

There’s one more volume which I hope will be the last but I haven’t no assurance that it will be. (William Faulkner, Faulkner in the University, 1959)

You can’t do nothing with nobody that doesn’t want to win. (Robert Frost, 1962)

When H.L. Mencken rewrote the Declaration of Independence in vernacular English in 1921, he peppered it with negative concord, such as ‘nobody ain’t got no right to take away none of our rights’. This recalls an observation by Jespersen in The Philosophy of Grammar, albeit about speech:

It requires greater mental energy to content oneself with one negative, which has to be remembered during the whole length of the utterance both by the speaker and the hearer, than to repeat the negative idea whenever an occasion offers itself, and thus impart a negative colouring to the whole of the sentence.

The Simpsons, episode 232

Logic

Many critics appeal to logic or maths to decry negative concord. Pam Peters’s Cambridge Guide to Australian English Usage understatedly rejects this line of argument as ‘dubious’. Huddleston and Pullum’s landmark Cambridge Grammar of the English Language calls it ‘completely invalid’:

The rule of logic that two negatives are equivalent to a positive applies to logical forms, not to grammatical forms. It applies to semantic negation, not to the grammatical markers of negation. . . . Those who claim that negative concord is evidence of ignorance and illiteracy are wrong; it is a regular and widespread feature of non-standard dialects of English across the world. Someone who thinks the song title I can’t get no satisfaction means “It is impossible for me to lack satisfaction” does not know English.

Jespersen again:

If we are now to pass judgment on this widespread cumulative negation from a logical point of view, I should not call it illogical, seeing that the negative elements are not attached to the same word. I should rather say that though logically one negative suffices, two or three are simply a redundancy, which may be superfluous from a stylistic point of view . . . but is otherwise unobjectionable.

And NC’s redundancy is superfluous only from a formally stylistic point of view. It’s generally used not in formal but in normal contexts, to which it is entirely suited. To apply Jespersen’s ‘negative colouring’ across a whole sentence is to express what Michael Adams calls, in a different domain of usage, ‘the potency of style’.

It’s not that negation in language never follows logical patterns: it often does, as in this sentence. But language and logic are not homologous systems. Linguistic negation is more complex – Language Log’s posts on misnegation show where the real trouble lurks – and can vary from one variety to another.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the argument from maths or logic depends on the type of logic selected. In algebraic logic, –a + –a = –2a, which is a stronger negative. Sticklers ignore this; maybe they’re multiplying those –a’s.

Politics of use

Be wary, then, when you see Aristotelian logic applied to language use, especially to enforce a specious ‘rule’ that just happens to target informal or non-standardized language. This strategy mischaracterizes language and often smuggles value judgements of people disproportionately excluded from prevailing power structures.

The stigma against negative concord in English is social and political, not grammatical. But it’s been repeated so often, for so long, that it has seeped into conventional belief along with dozens of other superstitions, zombie rules, and myths about English usage.

Negative concord is not a flaw in the countless varieties of English that use it. It’s a systematic, age-old grammatical feature with pragmatic or expressive purpose. Double negatives generally only ‘cancel out’ in contexts where that intent is obvious,6 or in dubious fantasies of a more orderly tongue.

Grammar rules emerge from how people use language. Invented rules asserted as dogma may have social utility but have no underlying authority. Context is vital: obviously NC is not normally suited to job applications and the like – though increasingly there are jobs where it makes no difference, and that’s fine.

Many people whose dialect lacks NC still draw on it in informal chat with friends and family, often in jest or through set phrases like ain’t no thing or it don’t make no never mind. This vernacularisation is available to us all, part of the great diversity of conversational modes.

Negative concord is unlikely to become part of standardized English any time soon, if ever – its status as a shibboleth is too entrenched. But if it’s part of your everyday or occasional usage, know that there ain’t no grammatical or linguistic reason to discard it or feel bad about it.

Cow and Boy Classics by Mark Leiknes

*

1 Example is from Otto Jespersen’s book Language: Its Nature, Development and Origin.

2 Anyone with knowledge of OE can feel free to correct or improve these glosses.

3 I usually call it standardized English now, to better indicate human agency and avoid suggesting that it’s a monolithic form received from on high. See Elizabeth Peterson’s note on terminology in Making Sense of “Bad English”. For sociolinguistic background, see for example ‘Standard English and standards of English’, ‘The Rise of Prescriptivism in English’, and ‘Ideology, Power, and Linguistic Theory’.

4 On the socioeconomics: Claire Childs’ doctoral thesis, which explores the development and use of different forms of negation in British dialects, reports a study that identified

an age-grading effect in the use of negative concord in Buckie, Scotland, where the youngest and oldest speakers used negative concord more often than the middle-aged group. The middle-aged group have greater involvement in the linguistic marketplace where there is increased ‘importance of the legitimized language in the socioeconomic life of the speaker’ (Sankoff & Laberge 1978: 241), so stigmatised variants are avoided.

5 As far as I know, negative concord, though excluded from Classical Latin, was part of Vulgar Latin, hence its occurrence in French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, and Spanish.

6 There are situations in which negative concord is potentially ambiguous, but context and delivery (prosody, real-world knowledge, etc.) usually resolve this. Some interesting research has found that children find negative concord easier to understand than litotes or true double negation. A couple of people said the same to me on Mastodon.

https://stancarey.wordpress.com/2023/02/27/dont-never-tell-nobody-not-to-use-no-double-negatives/

#ambiguity #descriptivism #dialect #doubleNegatives #grammar #language #languageHistory #languageMyths #linguistics #misnegation #multipleNegation #negation #negativeConcord #OttoJespersen #politicsOfLanguage #pragmatics #prescriptivism #RichardPryor #sociolinguistics #speech #standardizedEnglish #syntax #usage #usageMyths #writing