Mae’r trydydd post gwadd hwn gan yr Athro Calvin Jones am economi Cymru yn rhan o amcan Afallen o ddyrchafu telerau’r ddadl yng Nghymru ynglŷn â sut mae ein heconomi yn gweithredu – a beth y gellir ei wneud i’w gwella. Gallwch ddarllen blogbost cyntaf Calvin yma , a’i ail bost yma .

Llun pennawd: trwy garedigrwydd David Goehring.

- Beth yw Twf Economaidd?

- Llafur (newydd)

- Sgiliau i dalu’r biliau?

- Mwy o arian, dim problemau?

- Myfyrdodau Araf / Oedi Rhyfedd

There is no present in Wales,

And no future;

There is only the past,

Brittle with relics,

Wind-bitten towers and castles

With sham ghosts.

R.S. Thomas

Gwaedlyd uffern Ron, ysgafnhau myn.

Ar y llaw arall… Mae bob amser yn werth cael ychydig o R.S. A oes rhywbeth nad oes yno? Wrth iddo fownsio o gwmpas Cymru, o’r de i’r gogledd, o’r dwyrain i’r gorllewin, wedi’i drwytho gan y dirwedd a’r bobl, daeth yn gallu distyllu a chyfathrebu, yn Saesneg ac yna Cymraeg, rai o’r pethau prin hynny sy’n gyffredinol Gymreig. Pethau a fydd yn dychwelyd yr un nodau gwybodus yn y Glynne Arms ym Mhenarlâg, y Ship & Castle yn Aber, a’r Bunch of Grapes ym Mhonty. Rydyn ni’n ei gael, rydyn ni’n gwybod, rydyn ni ar y dibyn. Wedi’i wneud-i. Ychydig yn crap. Grumblers natur dda. Yn sownd. Mae un o fy ffrindiau mewnfudwyr bob amser yn cael ei daro gan ba mor oddefol ydyn ni (ei gair hi nid fy ngair i!).

Yn bennaf, dwi… kinda dathlu rhan fwyaf o hyn. Mae’n ein gwneud ni’n wahanol. Mewn rhai ffyrdd efallai hyd yn oed yn unigryw. Mae ein hanallu i nofio yn gryf yn y brif ffrwd yn agor dyfroedd cefn diddorol a phyllau dwfn, ac yn ein cymell i feddwl am fywyd a gwaith mewn ffyrdd sy’n fwy eang, cynhwysol a gofalus. Rwy’n hoffi hyn oherwydd rwy’n optimist yn y bôn. Ond nid yw’r cyfan yn dda. Weithiau, ac yn enwedig lle rwy’n byw, mae’n dal i deimlo fel diwrnod olaf streic y glowyr. Diwylliant marw yn taro ar wyneb dynol – am byth. Mae gan Bort Talbot a’r ardaloedd gwyllt gwledig eto i ddod.

Fe wyddoch chi, fy narllenydd cyson annwyl, mai fy ateb i hyn yw anghofio am berthnasedd a ffyniant economaidd, cofleidio lles, a gwyleidd-dra, a chymuned, a’n gilydd, mewn rhyw fath o ddirywiad-cyflwr-cyflwr-doughnut-post- economi carbon-insert-hippy-buzzword Mae gan bawb gwtsh mawr ac maent yn siopa yn Oxfam am lyfrau nodiadau cywarch yn lle Apple ar gyfer rhai alwminiwm wrth baratoi’n feddylgar ar gyfer dyfodol sythu…

Ond (a goddefa fi yma). Beth os ydw i’n anghywir?

gwn. Anodd dychmygu, ynte? Rhoddaf funud ichi.

Os yw twf economaidd o bwys – os mai dyna’r injan ar gyfer trawsnewid hinsawdd a’r newid ecolegol a lles – yna mae angen i ni feddwl sut y gallai Cymru dyfu’n gyflymach o ran CMC traddodiadol. Ynglŷn â’r hyn y mae damcaniaeth a thystiolaeth economaidd yn dweud wrthym am ei wneud; yn strwythurol, yn y tymor hir, yn gyfannol – i ddatblygu cyfeiriadedd twf yr ydym wedi bod yn ddiffygiol ers cenedlaethau.

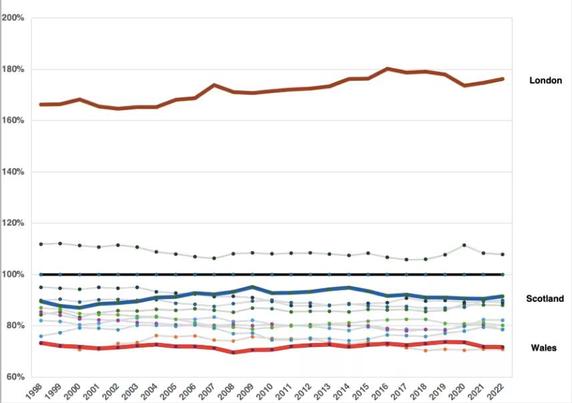

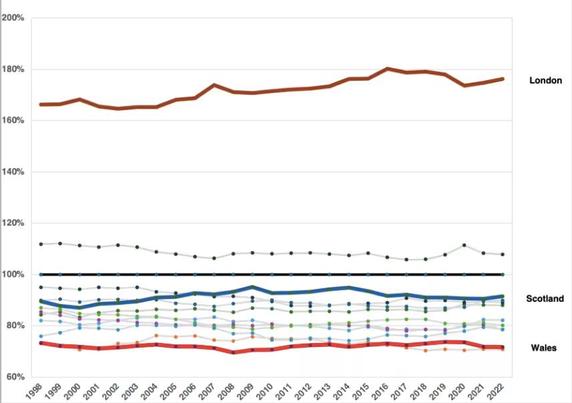

Ffigur 1: Gwerth Ychwanegol Crynswth y pen (DU=100)

Nid ydym. Yn lle hynny, rydyn ni’n ‘rhagamcanu’ ein heconomi – rydyn ni’n dychmygu porthladd rhydd yma, traffordd newydd yno, rhywfaint o sgiliau niwclear i’r brig, sy’n golygu hyd yn oed pan fydd gennym ni ddatganiad teilwng o’r problemau, mae gennym ni synnwyr cyfyngedig o’r hyn y gallai fod ei angen. mewn gwirionedd yn codi ein CMC y pen, yn y tymor hir, os ydym yn mynd amdani mewn gwirionedd, ac eithrio popeth arall.

Felly. Dyma fy nghymeriad.

Yn ôl i’r Hanfodion. Beth yw Twf Economaidd?

Twf economaidd yw’r hyn rydym yn ei alw pan fo mwy o bethau’n cael eu prynu a’u gwerthu mewn economi o’n dewis eleni, yn hytrach na’r llynedd – unwaith y byddwn yn anwybyddu effeithiau chwyddiant prisiau. Dyna fe. Ddim yn gymhleth, ynte? Hyd nes i chi ddechrau ei fesur, pan fydd angen i chi wneud pethau anodd fel casglu data ar yr holl brynu a gwerthu hwn – nwyddau, gwasanaethau, llafur – ac yna ailddyrannu gwerth y pryniant i’r man lle mae’n dod i ben (mae’n ddrwg gen i i ddweud wrthych nad yw eich bil ffrydio misol erchyll yn gwneud fawr ddim i economi Cymru). Rhaid i chi hefyd benderfynu a ydych yn poeni am faint cyffredinol yr economi (drwy fesur CMC), neu fwy faint o ‘stwff’ sydd wedi’i wasgaru o amgylch eich poblogaeth breswyl (lle mae CMC y pen yn bwysig).

Felly dyna’r ‘beth’. Beth am sut? Wel, os ydych chi eisiau economi fwy mae’n rhaid i chi gael mwy o ‘fewnbynnau’ yn cydweithio i wneud mwy o allbynnau. Mae’r mewnbynnau hyn yn cynnwys llafur a chyfalaf (gyda’r olaf yn cynnwys ffisegol a naturiol er enghraifft). Yn yr achos symlaf, os yw ‘lefel’ economi yn cael ei phennu gan gyfraniad y mewnbynnau hyn, ac yna dim ond os cynyddwch un neu fwy o fewnbynnau y mae twf yn bosibl. Er enghraifft, os bydd cyfranogiad menywod yn y gweithlu yn cynyddu, neu os bydd mewnfuddsoddwr yn dod â chyfalaf ar ffurf ffatri i wlad lai datblygedig – bingo! Ond nid oes rhaid i chi gynyddu pen ôl ar seddi bob amser. Cydnabuwyd ers tro bod cyfalaf dynol – addysg, hyfforddiant, sgiliau – yn chwarae rhan bwysig wrth gynyddu cyfraniad pob un, um, pen. Gall gweithwyr llythrennog, wedi’u haddysgu’n dda ac wedi’u hyfforddi’n dda gyfrannu mwy i gyd. Materion addysg.

Hyd yn hyn, mor dda. Ond mae dod o hyd i fwy o fewnbynnau yn anodd. Mae cynyddu llafur (er enghraifft trwy fewnfudo), cyfalaf, neu lefel addysg yn ymyriadau ‘unwaith ac am byth’. Yn sicr ni allant roi cyfrif llawn am y twf parhaus yr ydym wedi’i weld mewn rhai gwledydd ers cannoedd o flynyddoedd. Yn lle hynny, awgrymodd economegwyr fel Josef ‘yn onest, nid fampir o gwbl’ Schumpeter fod twf economaidd yn bennaf oherwydd ‘dinistr creadigol’ arloesi di-ben-draw; newid technolegol sy’n cynyddu cyfraniad ffactorau economaidd. Enghraifft dda o hyn yw cyn-rhyngrwyd, gallai fod wedi cymryd mis o aros ichi, taith i’r siop bapurau newydd a marwolaeth mil o goed er mwyn i’m, um, doethineb, fynd i mewn i’ch ymennydd trwy beli eich llygaid. Ac eto dyma chi, gyda mi yn eich lefelu’n economaidd, ar unwaith ar eich iPhone 15 16, newyn yn y gwely am 8.30AM. Ystyr geiriau: Shazam!

Gallwch, gallwch gropian i’r ystafell ymolchi am dabled, peidiwch â bod yn hir.

Felly mae’r twf economaidd parhaus sydd ei angen ar Gymru i gau’r bwlch ffyniant yn dibynnu ar ‘broses o drawsnewid parhaus. Y math o gynnydd economaidd … na fyddai wedi bod yn bosibl pe na bai pobl wedi mynd trwy newidiadau dirdynnol.’

Yna mae gwersi yma i Gymru: mwyhau ein mewnbynnau economaidd yn y gwaith yn y rhanbarth (a denu mwy pryd bynnag y gallwn); ac ysgogi – a gwreiddio – arloesedd i’r graddau nas gwelwyd erioed o’r blaen yn y gornel fach hon o’r byd.

Llafur (newydd)

Y peth cyntaf, ac amlycaf i’w nodi yw bod Cymru – ers cenedlaethau – wedi bod ar ei hôl hi o ran rhanbarthau llwyddiannus (neu hyd yn oed gyfartalog) o ran cyfran y bobl sy’n economaidd weithgar; hynny yw, mewn neu’n chwilio am waith. Mae hyn, o ran potensial CMC, adnoddau’n cael eu gwastraffu’n llwyr. Byddai gostwng ein cyfradd anweithgarwch economaidd o’r 28% presennol i gyfartaledd y DU o 22%, a chael yr holl bobl hynny (rhywsut) i mewn i waith yn ychwanegu 115,000 o bobl at y gweithlu a, hyd yn oed yng Nghymru ar gyflog isel, yn ychwanegu bron i £4bn. i’r llinell waelod.

Mae gwneud hynny’n ymarferol, wrth gwrs…yn anodd. Nid yw hyd yn oed galw uchel am lafur ôl-bandemig wedi gwneud llawer i symud y deial – oherwydd mae gennym broblem cyflenwad llafur. Mae pobl yn hŷn; yn sâl; efallai wedi eu dadrithio gan chwedlau eu rhieni a’u neiniau a theidiau; tan-fedrus; tan-ofalu, achos tan-ofalu … creiriau brau ym mhobman. Mae fy nghydweithiwr uchel ei barch Rob Huggins yn siarad, yn anfoddog, am le sydd wedi’i drwytho mewn diymadferthedd dysgedig. Ond mae o’n dod o Beddau felly mae’n siŵr y gallwch chi ei anwybyddu.

Serch hynny, er mwyn gwneud y defnydd gorau o adnoddau economaidd, mae’n amlwg bod yn rhaid i’r tyfwr alluogi, perswadio neu orfodi mwy o bobl yn ôl i (neu i mewn) i waith. Mae gorfodaeth wedi cael ei roi ar brawf dros y degawdau, fel arfer gan lywodraethau cenedlaethol y DU o’r math cywirol, a gyda llwyddiant cyfyngedig iawn, naill ai yn ystod Caledi neu yn ôl yn yr 1980au, pan allai llawer yng Nghymru gilio i fywyd teuluol cost isel, hobïau. a ‘hobbles’ gwaith anffurfiol, yn hytrach na dilyn anogaeth Norman Tebbit i ‘fynd ar eich beic’ a dod o hyd i waith.

Felly’r peth cyntaf ac amlwg i’w wneud yma yw peidio â gwarchae a chosbi (er y gallai hynny ddod), ond helpu’r rhai sydd eisoes eisiau gweithio ond na allant weithio. Nid yn yr economi y mae’r ymyriad allweddol, ond ym maes iechyd a gofal; ac nid yn unig yn y GIG yng Nghymru (neu’r Gwasanaeth Clefydau Cenedlaethol fel y mae cyfaill ymgynghorol yn ei alw), ond yn gyfannol, ym maes iechyd cyhoeddus ataliol a gwella mynediad at waith trwy drafnidiaeth, sgiliau, a gwell systemau gofal plant ac oedolion. Yn ffodus, mae hwn yn faes prin lle gall ein hebog Thatcherit ddod o hyd i bwrpas cyffredin gyda’n hipi hapus-clappy Cenhedlaeth y Dyfodol. Mae iechyd gwael yn brifo pawb. Fel un enghraifft yn unig, ofnadwy, mae’r coesau, y golwg a’r bywydau a gollwyd i ddiabetes Math 2 yng Nghymru yn cynrychioli trasiedïau dynol hynod o drasig ac yn wastraff llafur cynhyrchiol, gan na all y rhai sy’n cael eu cystuddio weithio, ac wrth i fwy a mwy o adnoddau gael eu dargyfeirio i’r swydd. gofalu amdanynt. Nid yw’r gost hanner biliwn a ffrwydrol i Gymru ond yn rhagfynegiad lleiaf o’r dyfodol. Mae hyd yn oed y damcaniaethwr economegydd mwyaf pengaled yn cydnabod bod buddsoddiad yn ofynnol ar gyfer twf yn y dyfodol. O ran ein pobl a seilweithiau galluogi, nid ydym yn gwneud llawer rhy ychydig ohono.

Felly fel man cychwyn, mae Eluned ac RT a Syr Keir yn ei hysgwyd yn gymrawd ac yn gwneud Cymru yn amgylchedd ‘sanitogenig’ sy’n creu iechyd yn hytrach nag amgylchedd sy’n ordew. Yn ffodus, rydyn ni’n gwybod rhywfaint o’r hyn sy’n gweithio. Felly sgriwiwch drethi i lawr (mwy) ar sothach siwgraidd ‘tan y pips (neu’r Coke equivalent) yn gwichian. Ailstrwythuro canol ein trefi, ein safleoedd cyflogaeth a’n mannau hamdden i orfodi’r 10,000 o gamau hynny, cyn belled ag y gallwn. A gwahardd yr holl hysbysebion a nawdd bwyd sothach a sothach, nid dim ond i blant (ac ydw, rydw i’n edrych arnoch chi’n gamblo).

Byddai’n braf meddwl y byddai’r uchod yn mynd yn bell i ddatrys problem gweithgaredd economaidd Cymru (ac, yn achos trethi bwyd sothach, yn cynhyrchu tipyn o arian parod ac yn ein gwneud yn hapusach ac yn iachach). Ond nid yw cael pobl i mewn i swyddi yn llawer o dda os ydynt yn swyddi gwael. Mae Cymru wedi gwneud yn rhyfeddol o dda ers datganoli o ran cynyddu cyfradd cyflogaeth menywod. Ond mae unrhyw effaith ar CMC wedi’i wanhau gan gynhyrchiant isel. Ym 1998, ychydig cyn y Chwyldro Gogoneddus, roedd y gwerth economaidd a grëwyd fesul awr a weithiwyd yng Nghymru yn 86.6% o gyfartaledd y DU. Yn 2021 roedd yn 84.1%.

Angen mwy o waith felly.

Sgiliau i dalu’r biliau?

Nid yw Cymru wedi’i haddysgu’n ddigonol, heb ei hyfforddi’n ddigonol ac felly heb lawer o sgiliau, ac mae hyn yn arbennig o wir am y rhannau tlotaf. O safbwynt twf economaidd, mae hyn yn codi cymaint o faneri coch fel bod clustiau Teirw yn plycio o Lawrenni i Licswm. Mae ein treftadaeth ddiwydiannol yn diflannu yn y cefn, gan ein gadael â heriau addysg a oedd yn anhydawdd wrth i wariant ar addysg disgyblion ac oedolion ostwng trwy Galedi, a COVID difetha galetaf ar y tlotaf. Yn y tymor hwy, mae’r galwadau enfawr y mae ein salwch yn eu gwneud ar wariant cyhoeddus yn golygu mai dim ond os bydd Cymru’n dod yn iachach dros y degawdau nesaf y bydd gwella cyfalaf dynol yn bosibl – fel y bydd o dan fy nghynlluniau synhwyrol a chymedrol uchod! Yr hyn sy’n peri mwy o bryder yw deall sut mae addysg yn cysylltu â thwf economaidd mewn unrhyw economi yn y dyfodol – ac yna sut rydym yn gweithredu’r cysylltiad.

Es i o gwmpas llawer o’r tai hyn yn 2019, gan feddwl sut olwg fyddai ar system addysg oedran ysgol addas ar gyfer y dyfodol yng Nghymru. Gadawaf i chi, annwyl ddarllenydd, edrych ar eich hamdden, ond byddwn yn myfyrio ar y ffaith fy mod wedi awgrymu yn ôl bryd hynny y dylid rhoi’r gorau i gymwysterau TGAU gan eu bod yn hyrwyddo model tra-arglwyddiaethol o ‘addysgu-i-arholiad’, dysgu ar y cof mewn llwybrau cul, ac i bob pwrpas. taflu blynyddoedd ffurfiannol disgyblion ‘anacademaidd’ i ffwrdd trwy lwybrau galwedigaethol a ystyriwyd yn wael.

Yn 2024, yng ngoleuni COVID, cyrchoedd syfrdanol AI (a’m profiad fy hun o wylio The Boy yn trafod TGAU a Safon Uwch), mae fy marn wedi caledu os rhywbeth. Mewn ysgolion a phrifysgolion, nid ydym yn addysgu ond yn achredu; ‘trefnu’ dysgwyr er hwylustod rhieni dosbarth canol a chyflogwyr sydd wedi ymddieithrio (ond yn ddilornus). Ac yn seiliedig ar ffactorau myfyrwyr sydd, yn ôl pob tebyg, â’r cysylltiad lleiaf â chynhyrchiant yn y dyfodol.

Mae sut olwg sydd ar addysg a hyfforddiant sy’n canolbwyntio ar dwf mewn byd AI sy’n cael ei ddominyddu, yn ogystal â’r hinsawdd, sy’n gyfyngedig yn ecolegol ac yn ddemograffig, yn bwnc rhy fras ar gyfer y blog hwn. Ond mae’n amlwg nad yw’n edrych fel fersiwn heb ddigon o adnoddau o system addysg Lloegr ym 1985 – sydd, i holl ryfeddodau mewn theori y cwricwlwm newydd, yn ei hanfod yr hyn sydd gennym cyn gynted ag y bydd plant yn cyrraedd eu harddegau. . Mae’r newidiadau bach i TGAU sydd i ddod yng Nghymru y flwyddyn nesaf yn adlewyrchiad o hyn. Mae symudiad tuag at fwy o asesu di-arholiad i’w groesawu, yn ogystal â’r amnaid i alluogi digidol (er bod y ddau yn codi materion yn ymwneud ag anfantais a’r adnoddau gofynnol), ond nid oes dim yn ymgynghoriad 2023 yn codi mater beth yw pwrpas TGAU o ran y gymdeithas gymdeithasol ehangach. – cyd-destunau economaidd a’r dyfodol. Chwiliwch yn ofer am y geiriau: economi, cymdeithas neu amgylchedd. Chwiliwch yn ofer am werth cyhoeddus neu resymeg twf economaidd ynghylch pam mae angen arholiadau cyhoeddus 16 oed o gwbl, pan nad oes bron unrhyw ddysgwyr yn gadael addysg yn yr oedran hwn. Mae’n debyg y bydd fy merch, nad yw wedi dechrau ar ei thaith TGAU eto, yn ymuno â’r gweithlu yn 2030 neu 2033. A ydym ni hyd yn oed yn ceisio rhoi’r sgiliau, y cymwyseddau a’r hyblygrwydd y gallai fod eu hangen arni? Ac os nad ydyn ni, sut allwn ni ddisgwyl iddi fod yn gynhyrchiol?

Spoiler: mae hi’n dysgu am 1066.

Mae gan Gymru’r pwerau i ailgynllunio’r ddarpariaeth addysg, cymwysterau a sgiliau yn llwyr er mwyn gwireddu ei dyheadau cenedlaethol ac eto… rydym yn parhau i hyfforddi cyfrifwyr a phlymwyr a chynllunwyr a harddwyr ac ie, economegwyr, yn union yr un ffordd ag unrhyw le arall – er gwaethaf hyn. wedi ein gadael am byth yng nghefn y pecyn economaidd. Gallem sothach ein hetifeddiaeth o broffesiynau a gweithleoedd gor-gul yn y 19eg ganrif o blaid rhywbeth llawer mwy cyfannol, pwrpasol sy’n canolbwyntio ar y dyfodol. Ac os yw hynny’n golygu ymwahanu â gweddill y DU, a diffyg symudedd allanol ymhlith ieuenctid medrus, wel… er mwyn mynd ar drywydd ein hamcan twf, nid ydym am iddynt adael beth bynnag, ydyn ni?

Mwy o arian, dim problemau?

Nid yw tyfu a gwella’r gweithlu yn golygu dim os nad oes gwaith da. Ac yma, wrth gwrs rydym yn golygu swyddi da yn y sector preifat: nid yw’r sector cyhoeddus di-elw syfrdanol o dreth, a’r trydydd sector a ariennir drwy losgach, (at ddibenion twf cofiwch), yn dda o gwbl. Ystyrir bod Cymru yn dioddef o brinder cyllid datblygu, yn enwedig i fusnesau bach a chanolig. Sef, yn y bôn, yr economi leol gyfan. Mae cyfateb cynnydd a gwelliannau mewn llafur gyda chynnydd mewn cyfalaf felly yn mynd â ni ar lwybr a sathrwyd ers tro gan economïau tlawd sy’n ceisio datblygu a moderneiddio: Denu, ac yn yr achosion gorau gwreiddio, Buddsoddiad Uniongyrchol Tramor.

Rwy’n gwybod beth rydych chi’n ei feddwl: mae Cymru wedi bod yma o’r blaen, a chydag ychydig o effaith weladwy ar gau ein bwlch CMC (er ei bod yn ddiddorol meddwl ble byddai CMC Cymru heb lwyddiannau FDI diwedd yr 20fed ganrif). A byddwn yn cytuno, ar adeg pan fo FDI byd-eang ar drai – a mewnfuddsoddiad i’r DU wedi bod yn dirywio’n sylweddol ers 2016 – mae gosod ein betiau yma yn ymddangos yn… optimistaidd. Yn wir, gallaf dynnu fy het economi twf (yr un gyda rotorau hofrennydd bach ar y brig) a llithro ar fy nghrocs cyffyrddus trychinebus i nodi mai’r peth allweddol ar gyfer twf economaidd yng Nghymru dros y ddegawd nesaf yw (o leiaf ) cadw’r cyfalaf tramor eisoes yma. Mae CMC preifat Cymru yn ddibynnol iawn ar lond llaw o gwmnïau nad ydynt yn lleol. Mae cefn fy amlen, fy mys yn yr awyr a llygad bach ar ddata CThEM yn meddwl bod hanner dwsin o gwmnïau – Airbus; Valero; GE yn Nantgarw; Dow; Tata a Celsa – sy’n cyfrif am dalp mawr o allforion rhyngwladol Cymru. Byddai cau unrhyw un o’r buddsoddwyr hyn, a’u henillion gwerthfawr i mewn, yn gwneud y mynydd twf yn anos i’w ddringo.

Nid yw hyn yn golygu na ellir gwneud dim byd newydd, ond byddai angen naws, ffocws a chysondeb ar strategaeth FDI sy’n canolbwyntio ar dwf – yn enwedig o ystyried ein diffyg (presennol) o sgiliau yn y gweithlu. Mae’r clwstwr lled-ddargludyddion sefydledig o amgylch Casnewydd yn enghraifft o lwyddiant ‘helics triphlyg’ y llywodraeth, diwydiant a’r byd academaidd. Ac arweiniodd ein perthynas hirsefydlog â Sony at Bencoed yn cynhyrchu dros 50 miliwn o unedau o’r Raspberry Pi, sy’n hynod amlbwrpas. Bydd y llwyddiannau nesaf yn dibynnu ar gynnig soffistigedig, wedi’i dargedu ac unigryw. Oni allai ein cryfderau yn Cyber a Fintech drosi yn gynnig clir i fuddsoddwyr yn seiliedig ar ddiogelwch? Ble mae ein heconomi hydrogen yn mynd? Beth ydyn ni’n anelu ato mewn gwirionedd?

Atebion ar gerdyn post os gwelwch yn dda.

Myfyrdodau Araf / Oedi Rhyfedd

You knew us better than we knew ourselves

And the truth it seems to hurt so much –

Bradfield/Wire/Moore

Dechreuais y blog hwn fel arbrawf meddwl, gan ddisgwyl atgyfnerthu fy nghredoau fy hun mai ofer oedd mynd ar drywydd twf economaidd cynyddol yng Nghymru yn ôl pob tebyg ac, o ystyried y cynnydd yn y defnydd o adnoddau a’r effeithiau byd-eang ar y De y mae’n ei awgrymu, hefyd yn anfoesegol. Rwy’n dal i gredu’r pethau hynny ond … mae ysgrifennu’r blog hwn hefyd wedi fy argyhoeddi bod yna rai synergeddau mawr posibl rhwng ffocws ar dwf, a chymdeithas sy’n gweithredu’n well yn gyffredinol.

Gallai rhai o’r gorgyffwrdd hynny arwain at bryderon ynghylch y cyfyngiadau ar ryddid dewis unigol, o ystyried y math o ymyriad gan y llywodraeth yr wyf yn ei awgrymu uchod, ond nid yw Cymru laissez faire yn Gymru twf uchel. Mae’n Gymru sâl. Cymru wedi ymddieithrio ac yn ddigalon. Cymru sy’n diystyru adnoddau sy’n werthfawr yn economaidd. Ac, fel y dywedais mewn man arall o’r blaen, Cymru sydd â diffyg ymreolaeth. Mae cyfalafiaeth wedi mynd mor anghywir yn ein cornel fach ni fel bod yna fesur da o ailwau cymdeithasol dan gyfarwyddyd y llywodraeth a fyddai’n diwallu anghenion twf i’r un graddau; economi lles; yr economi sylfaenol; economeg toesen…

Efallai y dylen ni ddadlau’r llanast – am beth yw pwrpas yr economi – ar ôl i ni ailddysgu hanfodion dim ond… gan gynnwys pobl, yn ddinesig ac yn economaidd.

Mae unrhyw Gymru sy’n fwy ffit ar gyfer y dyfodol yn Gymru sydd wedi newid. A dim ond gydag arloesi dwfn, wedi’i wreiddio, yn gylchol ac (byddwn yn dadlau) y daw’r newid hwnnw. Hefyd, y math o arloesedd y mae twf economaidd yn ben draw hebddo. Dyma’r cwestiwn ar y gorwel yr wyf wedi’i anwybyddu hyd yn hyn yn y blog hwn: sut ydym ni’n arloesi mwy (a gwell) yng Nghymru ac yna’n dal y buddion hynny? A allwn herio R.S. Thomas, a gadael ein chwareli mowldio a mwyngloddiau i greu dyfodol deinamig a llewyrchus i Gymru, yma yn y presennol?

Bydd blog nesaf a olaf Afallen ar gyfer 2024 yn gofyn y cwestiwn hwn yn unig.

https://afallen.cymru/?p=12581

#CalvinJones #Economi