A Year End Compendium of Outside the Box Antenna Ideas

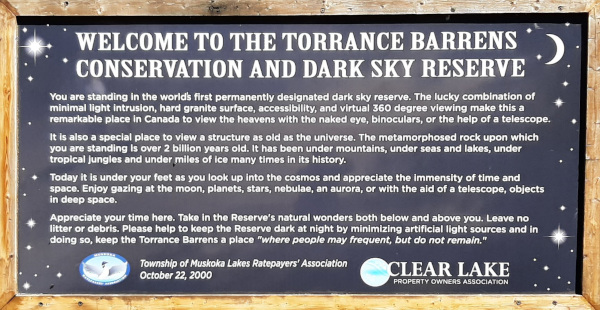

We have reached the end of another year of crazy ideas here at Ham Radio Outside the Box and a repeat of last year’s severe winter has gotten underway in southern Ontario. The daily temperature high remains well below freezing and the ground is buried under a thick blanket of snow already. I have tried to “Keep Warm and Carry On” with more off-the-wall outdoor antenna experiments but succumbed to the biting wind and had to retreat to the warmth of the shack.

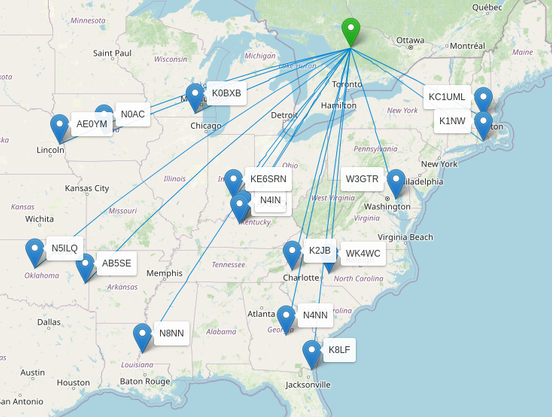

Here in the nice toasty warmth of my basement “Comms Room” I am surrounded by radio equipment, electronic gizmos, tools and almost enough wire to lay a new transatlantic cable. I also have computers. One of the computers runs the incredible HamClock program giving me instant access to updated solar propagation conditions, the current location of the International Space Station and real time data on the International HF beacon project.

Another computer is the one on which I am typing this post now. I recently realized that I have written so many posts related to field portable antennas I have built and tried that it would be a useful exercise to re-read them all. Heck, I surprised myself with some of the ideas that were posted and forgotten, but will now be resurrected. So, to end the year, I have composed a compendium of 35 of those posts – old and not-so-old – as a reference for readers to explore. I hope you may find some useful information for your own deployments.

I should stress that these are not all tried and tested designs. Some have worked so well I intend to keep them in my hambag for field portable radio operations. Others … well they were useful learning opportunities. Even if you only pick up a couple of tips such as the simplest, quick release method of attaching an antenna wire to the top of a pole the read will be worth your time.

NB: If you find any of these posts particularly interesting you can use the “Print” function on your computer and select “Save to PDF” or “Print to file” to keep a local copy.

ZZZZZ … ZZZZ … ZZZ

Ham Radio Outside the Box will now go into hibernation until the new year. Until then my best wishes go out to all in the hope that you will enjoy whatever religious or secular festival you celebrate at this time of year. Stay out of the cold!

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/11/04/a-simple-fix-for-my-broken-telescopic-whip/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/08/29/two-resonant-simple-wire-antennas-for-pota/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/09/23/a-simple-low-profile-multiband-antenna-for-pota/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/07/23/does-an-antenna-top-hat-really-work/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/07/11/an-outside-the-box-version-of-the-delta-loop-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2022/08/15/vertical-antenna-redesigned/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2022/07/30/no-antenna-no-problem/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2022/06/21/80m-band-antenna-fits-into-just-1-square-foot/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2021/12/17/an-easy-t2lt-portable-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2021/11/08/a-portable-vertical-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2021/09/13/a-most-unusual-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/05/14/matching-an-efhw-antenna-a-third-way/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/03/05/a-quick-and-easy-qrp-emergency-field-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/01/16/a-top-loaded-end-fed-half-wave-antenna-for-20m/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/12/12/a-clefhw-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/11/13/antenna-height-matters-true-or-false/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/08/16/how-does-the-speaker-wire-no-counterpoise-antenna-work/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/07/18/a-neat-trick-with-a-20m-efhw-wire-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/03/06/antennas-a-riddle-wrapped-in-a-mystery-inside-an-enigma/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/02/14/a-most-unusual-vertical-antenna-for-20m/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/12/06/a-simpler-field-expedient-rybakov-antenna-for-winter/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/11/05/an-upside-down-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/10/19/using-a-municipal-flagpole-for-an-antenna-fine-business/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/02/15/the-vp2e-a-strange-but-proven-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/02/09/what-in-heavens-name-is-a-rybakov-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/01/14/a-magic-ground-mobile-antenna/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2025/01/23/an-off-center-fed-sleeve-dipole/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2024/07/12/cutting-my-losses/

https://hamradiooutsidethebox.ca/2023/10/24/an-itsy-bitsy-teeny-weeny-upside-down-hf-whip/

Help support HamRadioOutsidetheBox

No “tip-jar”, “buy me a coffee”, Patreon, or Amazon links here. I enjoy my hobby and I enjoy writing about it. If you would like to support this blog please follow/subscribe using the link at the bottom of my home page, or like, comment (links at the bottom of each post), repost or share links to my posts on social media. If you would like to email me directly you will find my email address on my QRZ.com page. Thank you!

The following copyright notice applies to all content on this blog.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

#amateurRadio2 #antennas #counterpoise #cw #outdoorOps #portable #pota