New Boundaries = Adding some rhythm to your day! - #Music #Popular #Pop #Rock #Music #Song #BobbyPulido #TejanoMusic #PoliticalActivism #TexasRedistricting #DemocraticCampaign #Gerrymandering #LatinaRepresentation #Change #CulturalIdentity #Resilience #MusicAndPolitics #FightingForBeliefs #DistrictBoundaries #PoliticalJourney #SouthTexas #MidtermElections - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R8Ka0-eMTz0

#TejanoMusic

On Tejano Music 8: J.D. Mata, Music Pioneer and Performer

Author(s): Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Publication (Outlet/Website): The Good Men Project

Publication Date (yyyy/mm/dd): 2025/

A seasoned Musician (Vocals, Guitar and Piano), Filmmaker, and Actor, J.D. Mata has composed 100 songs and performed 100 shows and venues throughout. He has been a regular at the legendary “Whisky a Go Go,” where he has wooed audiences with his original shamanistic musical performances. He has written and directed nerous feature films, web series, and music videos. J.D. has also appeared in various national T.V. commercials and shows. Memorable appearances are TRUE BLOOD (HBO) as Tio Luca, THE UPS Store National television commercial, and the lead in the Lil Wayne music video, HOW TO LOVE, with over 129 million views. As a MOHAWK MEDICINE MAN, J.D. also led the spiritual-based film KATERI, which won the prestigious “Capex Dei” award at the Vatican in Rome. J.D. co-starred, performed and wrote the music for the original world premiere play, AN ENEMY of the PUEBLO — by one of today’s preeminent Chicana writers, Josefina Lopez! This is J.D.’s third Fringe; last year, he wrote, directed and starred in the Fringe Encore Performance award-winning “A Night at the Chicano Rock Opera.” He is in season 2 of his NEW YouTube series, ROCK god! J.D. is a native of McAllen, Texas and resides in North Hollywood, California. Tejano music shaped Mata’s artistic identity, influencing his career in music, acting, and filmmaking. As a founding figure, he dedicated himself to the genre, writing original music and pioneering the synthesizer sound that defined Tejano. He emphasizes its authenticity, contrasting it with inauthentic artists. Mata highlights Tejano’s broad reach, from weddings to festivals, and the emotional depth in its lyrics. He reflects on Tejano’s role in his journey, from early performances to navigating Hollywood, using intuition honed in the music industry. Despite challenges, he sees Tejano as an enduring legacy that inspires artists and audiences alike.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: So, it’s been a while. I want to discuss incorporating various elements to form a perspective on contemporary Tejano music. We discussed some of the major figures and families in Tejano music and the German and Mexican influences.

We also talked about being in Texas, making your way to California, and the difficulties there. People may know that you have a dual career in acting and music. Additionally, we discussed your long history of choir conducting.

How do these various elements—acting, choir conducting, directing, and producing with Lance and Rick in their long-standing Republican-Democrat debates—come together to influence Tejano? You have diverse skills in many areas, but your main focus has not always been Tejano music. Instead, your career has evolved, with Tejano music emerging as a central element.

J.D. Mata: Tejano music was like a birth in terms of my career. Learning to play the piano and guitar could be considered the “sperm,” while my first stage production in sixth grade could be the “egg.” I auditioned for the lead role in Funky Christmas, a musical Christmas program at Seguin Elementary in McAllen, and got the part. That was the moment where, metaphorically speaking, the sperm met the egg—where my journey as an entertainer truly began. But the “baby” was born when I started playing Tejano music professionally.

That experience informed everything. It was when I had to apply my musical skills—skills my dad taught me on the guitar, my piano abilities from the band, and my natural singing talent. I also had to incorporate my stage presence and acting experience because, as the frontman of a band, you are not just a musician—you are a performer.

It’s a production. There has to be charisma, animation, and energy. You must engage the audience, keep them excited, and make the performance come alive. Stagecraft is an essential part of that.

Beyond that, Tejano music is also a business. As the founder and leader of my Tejano band, I had to learn the business aspects—determining fair rates and managing finances. For example, what goes into setting the rate if we are hired to play a wedding? We must consider factors such as how much to pay the musicians, travel expenses, equipment costs, and venue requirements.

Obviously, any company CEO earns more than the employees because they assume more risk and have more at stake.

For me, it was about ownership and responsibility. I owned all the equipment—I had to buy it myself. I was the founder of the band and the writer of all the music. I assumed all the risk. It was my name on the business and on the music itself. It was my van that transported all the equipment. I was the one setting up everything before each show.

So, there’s that aspect of it. How much do the musicians get? What percentage do I get as the founder, lead singer, and band leader? Then, you also have to factor in gas expenses—how far are we travelling? That needs to be accounted for as well. How many hours are we playing? Many people think, “Oh, you’re only playing for two hours,” or, “We’re just hiring you for a one-hour performance.”

But they don’t consider the time it takes to drive to the venue, unload and set up the equipment, do the sound check, perform, break everything down, and then load everything back up. That’s where the rate comes from. These are principles I learned from my experience in Tejano music. Being an entertainer shaped everything I do now—as a filmmaker, actor, musician, and even as my publicist. I had to promote the band. I was often my own manager.

And through those experiences, I developed a strong intuition for spotting people who are not genuine—what I call “bullshit artists.” Whether it’s within the band or in the business side of the industry, there’s always one person who disrupts the harmony. It could be envy, entitlement, or just being disgruntled, but there’s always one person who ruins the synchronicity of the group. I’ve learned to recognize those patterns quickly.

All of this—my time as a Tejano artist, band leader, entrepreneur, and performer—has shaped me. It has guided my ability to navigate Los Angeles as an actor, filmmaker, choir director, and even dancer.

Most recently, I played at an Oscar afterparty in Beverly Hills. This guy came up to me and said, “Hey man, I love your look. Are you signed with anyone?” Because of my experience, I’ve developed an intuition for who is legit and who isn’t—something I honed in my Tejano days and continue to sharpen. This guy seemed legit. Sure enough, today, I met with him. He’s a film director, and he cast me in his movie.

Of course, it took effort. I had to drive all the way to Beverly Hills from North Hollywood. Before that, I had just played in Simi Valley. But that’s part of the hustle, and it’s all informed by my journey in Tejano music.

I played at an assisted living facility. I’m the ‘rock god of assisted living homes.’ Then, I drove to Beverly Hills and met with the director. I spent about three to four hours on the road, and I used a lot of gas, but I knew it would be worth it.

I could tell this guy was legit, and it played out that way. It’s interesting to analyze my Tejano experience and dissect how it has influenced everything I do. I’m still the same entertainer I was back in my Tejano roots. But now, I also recognize that there is a business aspect to what we do as artists.

As I told you earlier, when I started, Tejano music didn’t exist in the way we know it today. My first band was one of the pioneers of Tejano music. The name “Tejano” first became associated with our type of band, which featured a keyboard, synthesizer, and bass guitar. These instruments replaced the traditional horn section and accordion, which had previously defined the sound.

Different phases of my career incorporated various elements. At times, we included horns and trumpets. Still, for the most part, we were a genuine, bona fide Tejano band because we embraced the synthesizer sound as a key element of our music.

Jacobsen: Who were your influences as a pianist?

Mata: We didn’t have influences—we were the influencers. I was one of the first to form a Tejano band in 1981, and the genre itself didn’t gain recognition until around 1983 or 1985. When I was a senior in high school, the term “Tejano” still wasn’t widely used to define our style of music.

People ask what kind of music we played. The truth is we wrote our own material. We performed all original songs and adapted traditional standards—accordion-driven conjunto music, mariachi songs, and other regional influences—into Tejano music.

For example, if a melody was originally played on a trumpet or accordion, we translated it into a synthesizer line, which became a defining characteristic of Tejano music. Just as the accordion is synonymous with conjunto, and the trumpet is essential in orchestral or mariachi genres, the synthesizer became the signature sound of Tejano.

Because I developed that creative muscle early—starting in junior high, high school, and college—when I came to Los Angeles and couldn’t immediately find work as an actor, I instinctively created my own opportunities. It felt natural. I started making my own films just like we had created a genre from scratch.

I had already been a writer—first for music—so transitioning into filmmaking was a natural extension of what I had done since my early years.

That’s what I’ve been doing my whole life. I didn’t discover The Beatles until I was in college. I became a huge Beatles fan, but it wasn’t until college because I was playing Tejano music, man. I was doing my own thing. I was my own Beatles. I was Billy Joel.

I was rock, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and Tejano music. That genre has had a huge impact on me and shaped who I am. I am one of the most interesting Mexican American entertainers and artists in the world.

Jacobsen: Your efforts in co-developing Tejano in its early days weren’t just about blending Mexican and German influences. They were about contributing to American music culture.

Mata: 100%. That’s interesting you say that, Scott. In the 1980s, when Tejano music was emerging, there was no Internet. There were small digital rumblings—bulletin board systems, early forms of online communication—but nothing like social media.

I remember my friend, Juan Mejia, who is now a dean at a university, telling me, “Man, you can talk to people around the world or in the U.S.” I was like, “What?” This was in 1985. But there was no widespread Internet, no way to instantly share music beyond local radio stations and word of mouth.

And where we lived in South Texas—Texas is huge. I grew up five miles from the Mexican border, way down south. The nearest big city was San Antonio or Austin, a five-hour drive. Corpus Christi was closer, but there was a lot of nothing between South Texas and the rest of Texas, let alone the rest of the U.S. And then you had Mexico.

So, we were our own country. We weren’t fully Mexican, but we weren’t fully American either. We were true Mexican Americanos—American Mexican Americans. And that was beautiful because it allowed us to create our own identity.

As you said, that identity has become authentic—a recognized and beautiful strand of American culture. I’d say I’m a part of that because I’m now sharing my movies and my music with a broader American audience.

And, of course, Selena.

She was the queen of Tejano music. The beauty that she brought from Mexican-American Tejano culture—the music, the melodies, the lyrics, the emotions—are intangibles that, when you listen to her, create feelings of euphoria. She is now woven into American culture. She was a real artist—a key figure, a peak voice in the development of Tejano.

Jacobsen: One other mission—you’ve talked about being able to identify not just the real ones but also the real ones by proxy. That is, identifying the bullshit artists. So, the nonreal ones—in more polite terms. When you sense bullshittery in artists, even in full Tejano presentation—people who think they have the right stuff but aren’t truly playing Tejano—what do you look for? What are your indicators?

Mata: That’s a good question. First of all, the instrumentation. I’m a purist. I’m a textualist.

I’m one of the founding fathers, baby, so you can’t bullshit me. If you’re going to play Tejano in its pure form, I don’t want to see a band consisting of just an accordion, bass, and guitar. That’s not a Tejano band. That’s panto music.

You cannot call yourself a Tejano artist if you have a big horn section without keyboards or synthesizers. I’m sorry—that’s not Tejano music. Authentic Tejano music must have a keyboard playing synthesizer lines in a jazzy, syncopated, harmonic way. That’s bona fide Tejano music. If you don’t have that, you’re not playing Tejano.

Now, I’m painting with broad strokes here, but I’ll say this: if you’re not from Texas, you’re not playing Tejano music. That being said, if you are from Texas and you’re Caucasian but play authentic Tejano music, then you are a Tejano artist.

Jacobsen: So, that’s your standard—Tejano music, exactly. It’s a big discussion—kind of like in the rap community, where people debate who should be accepted as a great artist or not. I’m not deeply involved in that world, so I can’t comment much. But I do know that hip-hop’s originators were DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force, and the Sugarhill Gang. So, in a way, you’re talking about yourself in those terms—vis-à-vis Tejano music.

Mata: Right.

Tejano music has experienced highs and lows. It has gone through a rough period over the last fifteen to twenty years.

And going back to spotting bullshittery—this is the real deal I’m giving you. These are thoughts and analyses I’ve never seen written anywhere. But I’m telling you now because it’s authentic.

One of the things about a true Tejano artist is that they will play anywhere. A real Tejano artist will play weddings, quinceañeras, church festivals, concerts—you name it. You’ll even see a Tejano artist performing at the freaking market.

Catholic War Veteran halls.

We play everywhere.

That’s what’s fascinating about Tejano artists—we can adapt. Meanwhile, a punk rocker or a thrash artist? They’re limited in where they can play. Tejano music is freaking homogeneous, man.

Tejano music can be played anywhere because of its danceable vibe. It’s not like rap, where some of the lyrics can be explicit. I don’t want to say raunchy, but they can be more aggressive.

Tejano music is different. It’s about emotions—wanting your girl back, but she doesn’t want to take you back. That’s authentic Tejano music.

It’s pure. It’s pure in its form. That’s why Selena brought it back to the forefront. One of the key ingredients of a genuineTejano artist is the lyrics.

Tejano’s lyrics carry a sense of wholesomeness. It’s not necessarily as poetic or verbose as a Bob Dylan song, but in terms of the message—it’s heartfelt and authentic. If you’re out here rapping about f**ing someone and claiming to be a Tejano artist, then you aren’t one.

Jacobsen: It’s like the difference between Slick Rick telling a story, Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise, or DMX narrating his experiences—versus modern rappers who pretend to be gangsters. They don’t live necessarily what they’re talking about. A lot of them are putting on an act.

I dated a Bolivian-Japanese person who had a deep appreciation for Karol G. She described Karol G’s music in a way that sounded similar to how you’re describing Tejano’s music. It wasn’t just quite romantic or sentimental—it carried a deep longing without being forlorn. It’s about evoking emotions without necessarily saying them directly.

Mata: Exactly—100%.

Jacobsen: That’s the poetic nature of it.

Mata: There’s an ethos to it, right? Ethos is tied to Tejano culture itself. It’s deeply Roman Catholic. That background informs the music, the values, and the way emotions are expressed. And Tejano music has impacted me to this day. I’m 59 years old now, and I started when I was 13. It’s been with me my entire life.

Jacobsen: How would you describe what Tejano means to you and what you mean to Tejano?

Mata: Tejano is part of my identity.

In terms of what’s important to me, my higher power—whom I call God—comes first. Then, my family. Then, my career.

And the birth of that career was Tejano music.

To me, Tejano is part of my existence.

Tejano music is part of everything I do. If it weren’t for Tejano music—if it wasn’t in my metaphorical genetic makeup as an artist—I wouldn’t be here in Los Angeles. That’s why I speak so affectionately about it and why I try to be as authentic as I can in this series. Tejano music isn’t just something I do—it’s in me. It’s in my blood. It’s part of me like an extra limb, an extra eye—an artistic eye that I was born with, that I grew into, that I helped shape. I was one of its founders, and that means something. It means love. It means passion. It even means hate—not hate in the literal sense, but in the sense that Tejano music has brought me pain. It has brought me anguish. Maybe that’s another discussion for another time, but Tejano has been the source of everything—joy, pain, struggle, success.

To answer the second part of your question—what Tejano means to me and what I mean to Tejano—I would say this: Tejano gave me everything, and I gave everything to Tejano. I was one of the founding fathers. Of course, there were many founding fathers, but I was there at the beginning. My music was on the radio. We played countless concerts, festivals, church events, and weddings. We played everywhere. And who knows who was in those audiences? Maybe some kid saw us and got inspired. Maybe my music influenced a young musician watching in the crowd. Maybe my piano band—my music—sparked something in someone. I don’t know. But I do know that I gave everything I had to it. Every dollar I made went back into the band. Every ounce of creativity I had was poured into my music.

I was so dedicated to Tejano music that I didn’t even listen to The Beatles until college. I was too busy creating Tejano music. I wasn’t just influenced by something—I was creating something. And what did I give back to it? Well, it’s not just me—we, the early pioneers of Tejano, gave everything. And the proof is in the fact that Tejano music still exists. It’s still here. It’s still thriving. The genre didn’t fade away—it grew. And I’m not saying this to be arrogant or grandiose. It’s just the truth. We were the founders. We played all over South Texas, from the Rio Grande Valley to San Antonio. I don’t know exactly who we impacted, but I know we did. Maybe one person. Maybe a hundred. Maybe a thousand. Maybe even performers who went on to have their own careers. Maybe fans who became lifelong lovers of the music.

And then, of course, there’s the other side of it—the struggles, the setbacks. We were so close to making it big. But, as I mentioned earlier, sometimes all it takes is one person to ruin the chemistry of a band. And that happened to us. One dimwit ruined what could have been something even bigger. That’s just how it goes sometimes. But the truth is, we were the seed that sprouted Tejano into something more. And we didn’t just grow—we pollinated. We spread our sound. We influenced future Tejano artists. We reached people who fell in love with the genre.

Jacobsen: Pollination.

Mata: Right. That’s a good way to put it. That’s a good way to end this. That’s enough for me. How about you?

Jacobsen: I agree.

Mata: I’ll see you then. Take care.

Jacobsen: See you then. Take care.

Last updated May 3, 2025. These terms govern all In Sight Publishing content—past, present, and future—and supersede any prior notices. In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons BY‑NC‑ND 4.0; © In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen 2012–Present. All trademarks, performances, databases & branding are owned by their rights holders; no use without permission. Unauthorized copying, modification, framing or public communication is prohibited. External links are not endorsed. Cookies & tracking require consent, and data processing complies with PIPEDA & GDPR; no data from children < 13 (COPPA). Content meets WCAG 2.1 AA under the Accessible Canada Act & is preserved in open archival formats with backups. Excerpts & links require full credit & hyperlink; limited quoting under fair-dealing & fair-use. All content is informational; no liability for errors or omissions: Feedback welcome, and verified errors corrected promptly. For permissions or DMCA notices, email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com. Site use is governed by BC laws; content is “as‑is,” liability limited, users indemnify us; moral, performers’ & database sui generis rights reserved.

#culturalIdentity #musicalAuthenticity #performanceLegacy #synthesizerSound #TejanoMusic

Texas Tornados – Ay Te Dejo en San Antonio

https://wgom.org/2025/08/05/texas-tornados-ay-te-dejo-en-san-antonio/

Legendary accordionist Flaco Jimenez dies at 86 | AP News

#arts #music #TejanoMusic #conjunto #deaths #whodied #rip #obits #obituaries #RestInParadise

Corpus Christi.

corpus Christi #texas #corpuschristitx #cctx #selenaquintanilla #corpuschristitexas #selena #comolaflor #selenaquintanillaperez #houston #selenaylosdinos #sanantonio #corpuschristiphotographer #bidibidibombom #corpus #dreamingofyou #austin #music #shoplocalcc #queenoftejano #selenaq #tejanomusic #lareina #toselenawithlove #selenaqueen #selenafans #dallas #southtexas #tejanoqueen #selenaandchris

https://itsmostamazingindia.wordpress.com/2025/06/19/corpus-christi/

Johnny Rodriguez – That’s The Way Love Goes

https://wgom.org/2025/05/16/johnny-rodriguez-thats-the-way-love-goes/

Remembering Selena today, gone 30 years now. 💔 We have Selena's posthumously released Dreaming of You (1995) on the 1001 Other Albums list so I really wanted to do its spotlight today, but I'm the one who had added it and I feel like I've been choosing too many of my own submissions lately, so I'm going to wait a bit to post a spotlight. Highly recommend listening to this one today anyway.

Selena & Barrio Boys -- 1994 Tejano Music Awards

¡Selena vive!

The article has a wonderful photo from the 1994 Tejano Music Awards.

How Museums Are Preserving and Celebrating Selena's Legacy | At the Smithsonian| Smithsonian Magazine

(4) GUACAMOLE - Laura Denisse y los Brillantes #TexasTornados #tejanomusic - YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgGNPADolXg

Selena -- Bidi Bidi Bom Bom*

https://youtu.be/RKGbjJarMeA?si=AgKpOliaBG4QI1Mn

With the delightfully catchy heartbeat-cum-nonsense lyric, Tejano artist Selena's song was a nineties musical landmark. Her murder in 1995 was a great loss; she could have been a megastar.

Two decades later, kids in Texas still know "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" and "Como La Flor".

* Not be confused with the Hanukkah song "Bidi Bom"!

Drinking my second glass of Chilean merlot.

#Selena #TejanoMusic #MastodonMusic #Nineties #BidiBidiBomBom

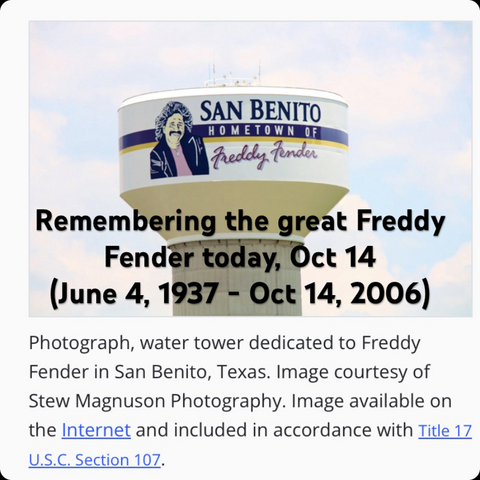

Remembering the great Freddy Fender: June 4, 1937 - October 14, 2006

Born Baldemar Garza Huerta in San Benito, Texas.

#CorpusChristiTexas #CountryMusic #TejanoMusic #LatinMusic #CrossoverArtist #Hits #BeforetheNextTeardropFalls #WastedDaysandWastedNights #SecretLove #GrammyAward #BillboardCharts #TexasTornados

If my limited sample size is accurate “Hey Siri play tejano music” results in a playlist that includes any song that contains the word “enchilada” (being actual tejano music is not necessary)

#tejanoMusic #appleMusic #funny