28 Years Later: political parallels, pregnant zombies and a peculiar ending – discuss with spoilers https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/23/28-years-later-discuss-with-spoilers #Actionandadventurefilms #AaronTaylor-Johnson #JackO'Connell #28YearsLater #RalphFiennes #Horrorfilms #JodieComer #DannyBoyle #Dramafilms #Culture #Zombies #Film

#dramaFilms

Deliver Me From Nowhere: first trailer for Oscar-tipped Bruce Springsteen biopic https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/18/bruce-springsteen-deliver-me-from-nowhere-trailer #BruceSpringsteen #JeremyAllenWhite #StephenGraham #JeremyStrong #Dramafilms #Biopics #Culture #Music #Film

F1 the Movie review – spectacular macho melodrama handles Brad Pitt with panache https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/17/f1-the-movie-review-brad-pitt #LewisHamilton #MaxVerstappen #JavierBardem #Dramafilms #FormulaOne #Motorsport #BradPitt #Culture #Ferrari #RedBull #Sport #Film

‘Always something I can watch’: why Spotlight is my feelgood movie https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/16/spotlight-feelgood-movie #MichaelKeaton #RachelMcAdams #LievSchreiber #StanleyTucci #MarkRuffalo #Dramafilms #Spotlight #Religion #Culture #Boston #Film

‘Chaps frame the buttocks in a beautiful way’: John C Reilly on Magnolia, moving into music – and his nice bum https://www.theguardian.com/music/2025/jun/12/john-c-reilly-magnolia-music-vaudeville #PaulThomasAnderson #ScarlettJohansson #JohnCReilly #Comedyfilms #Dramafilms #TomWaits #Culture #Comedy #Music #Film

Nashville at 50: Robert Altman’s defining masterpiece of the 1970s https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/11/nashville-movie-1975-robert-altman #ShelleyDuvall #JulieChristie #RobertAltman #LilyTomlin #Dramafilms #Nashville #Country #Culture #Music #Film

Dragonfly review – haunting, genre-defying drama of lonely city living https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/07/dragonfly-review-andrea-riseborough-brenda-blethyn-tribeca-festival #Tribecafilmfestival #AndreaRiseborough #Dramafilms #Culture #Film

Straw review – Taraji P Henson rises above Tyler Perry’s tortured Netflix thriller https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2025/jun/06/straw-movie-review-tyler-perry #TarajiPHenson #TylerPerry #Dramafilms #Thrillers #Netflix #Culture #Film

The Life of Chuck review – unmoving Stephen King schmaltz https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/05/life-of-chuck-movie-review-stephen-king #ChiwetelEjiofor #TomHiddleston #StephenKing #KarenGillan #MarkHamill #Dramafilms #Culture #Film

Showgirls review – Paul Verhoeven’s kitsch-classic softcore erotic drama is pure bizarreness https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/04/showgirls-review-paul-verhoeven-erotic-melodrama #KyleMacLachlan #Dramafilms #Worldnews #LasVegas #Culture #USnews #Film

‘People would prevail’: why The Towering Inferno is my feelgood movie https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/jun/02/feelgood-movie-towering-inferno #Actionandadventurefilms #SteveMcQueen #FayeDunaway #PaulNewman #Dramafilms #OJSimpson #Culture #Film

Walk on the wild side: Gillian Anderson and Jason Isaacs on their epic hiking movie The Salt Path https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/30/gillian-anderson-jason-isaacs-the-salt-path-raynor-winn #Autobiographyandmemoir #Health&wellbeing #GillianAnderson #Filmadaptations #Biographybooks #Lifeandstyle #JasonIsaacs #Dramafilms #Walking #England #Culture #Hobbies #Fitness #UKnews #Books #Film

Walk on the wild side: Gillian Anderson and Jason Isaacs on their epic hiking movie The Salt Path https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/30/gillian-anderson-jason-isaacs-the-salt-path-raynor-winn #Autobiographyandmemoir #Health&wellbeing #GillianAnderson #Filmadaptations #Biographybooks #Lifeandstyle #JasonIsaacs #Dramafilms #Walking #England #Culture #Hobbies #Fitness #UKnews #Books #Film

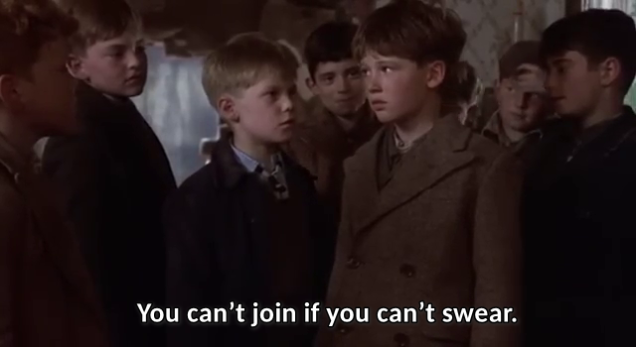

Swearing as a rite of passage

Think about your earliest swearing. Did you graduate from euphemisms? (As a child I used sugar, drat, and flip/feck for shit, damn, and fuck.) Or did you jump right into prodigious profanity? Did you practise in private, and did you try out your new vocabulary among friends – or in front of shocked family members?

Or maybe, as in John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987), you were forced to swear. In this period film, which reimagines the director’s childhood in London during the Blitz, coming of age meant coming to terms with the senselessness of war and the elusive sense of swearwords.

As Boorman writes in his wonderful memoir, Adventures of a Suburban Boy, the film was “a way of looking at my personal mythology”. For a child in wartime, some of that mythology centred on ammunition, an object of constant fascination:

We kids rampaged through the ruins, the semis [semi-detached houses] opened up like dolls’ houses, the precious privacy shamefully exposed. We took pride in our collection of shrapnel. Most of it came from our own anti-aircraft shells, which also did more damage to roofs than the Luftwaffe. I often picked up fragments that were still hot and smelt of gunpowder. . . . The most prized acquisition of all was live ammunition. We would lock bullets in a vice and detonate them by hammering nails into their heads.

This is recreated in Hope and Glory in a scene where Billy – Boorman’s surrogate – encounters a gang of boys while out scouring the ruins for treasure. They want to see what he’s made of and conduct some routine intimidation, before realising their common enemy. The mood warms enough for the leader, Roger, to invite Billy into the gang. But first he must pass an unusual test (transcript from 2:10 below):

Roger: Do you wanna join our gang?

Billy: Don’t mind.

R: Do you know any swear words?

B: Yes.

R: Say them.

B: [hesitates]

R: Go on. Say them. You can’t join if you can’t swear.

B: Uh, I only know one.

All: [laughter]

R: Well say that one then.

B: [hesitates]

R: [shoves Billy] Go on.

B: Fuck.

All: [gasp]

R: That word is special. That word is only used for something really important. Now repeat after me: Bugger off.

B: Bugger off.

R: Sod.

B: Sod.

R: Bloody.

B: Bloody.

R: Now put them all together: Bugger off, you bloody sod.

B: Bugger off, you bloody sod.

R: [smiles] Okay, you’re in.

All: [cheering]

R: Let’s smash things up.

All: [loud cheering]

There’s much to enjoy in this scene. The specific innocence of children of that age and time. The camaraderie waiting behind their show of toughness. Their unselfconscious naïveté about swearing; their awe at fuck.* This viewer’s immense relief that none of them is hurt by the reckless play with explosives.

And I love how swearing plays a central role in Billy’s initiation. A string of (very British) swears is the key, the set of magic words that establishes rapport with a group of his peers, dissolving the boundary between outsider and insider and nudging him just slightly towards adulthood.

*

* For a Boorman film that went in another direction, see my post on avoiding swear words in the making of Deliverance.

#bloody #bugger #Children #comingOfAge #dramaFilms #filmmaking #films #fuck #HopeAndGlory #JohnBoorman #sod #swearing #swearingInFilms #taboo #tabooLanguage #tabooWords #war #warFilms #WorldWarII

The Salt Path review – Gillian Anderson and Jason Isaacs hike from ruin to renewal https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/28/the-salt-path-review-gillian-anderson-and-jason-isaacs-hike-from-ruin-to-renewal #Autobiographyandmemoir #Health&wellbeing #Filmadaptations #GillianAnderson #MarianneElliott #Lifeandstyle #JasonIsaacs #Dramafilms #RaynorWinn #Somerset #Cornwall #Walking #Culture #UKnews #Dorset #Books #Devon #Film

The North review – old friends’ trek through the Highlands might be the ultimate hiking film https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/28/the-north-review-old-friends-trek-through-the-highlands-might-be-the-ultimate-hiking-film #Health&wellbeing #Lifeandstyle #Dramafilms #Scotland #Walking #Culture #Fitness #Hobbies #UKnews #Film

Autumn review – amazing landscape plays central role in Portuguese wine-family drama https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/27/autumn-review-amazing-landscape-plays-central-role-in-portuguese-wine-family-drama #Lifeandstyle #Dramafilms #Worldnews #Portugal #Culture #Family #Europe #Film

Mountainhead review – tech bros face off in Jesse Armstrong’s post-Succession uber-wealth satire https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/23/mountainhead-review-tech-bros-face-off-in-jesse-armstrongs-post-succession-uber-wealth-satire #JasonSchwartzman #Television&radio #JesseArmstrong #Comedyfilms #SteveCarell #Dramafilms #Succession #Culture #Comedy #Film

The Mastermind review – Josh O’Connor is world’s worst art thief in Kelly Reichardt’s unlikely heist movie https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/23/the-mastermind-review-josh-oconnor-kelly-reichardt #Periodandhistoricalfilms #Cannesfilmfestival #KellyReichardt #JoshO'Connor #Dramafilms #Crimefilms #Worldnews #Festivals #UScrime #Culture #USnews #Film

The Young Mother’s Home review – outstanding return to form for the Dardenne brothers https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/may/23/jeunes-meres-the-young-mothers-home-review-dardennes-brothers #Parentsandparenting #Cannesfilmfestival #Lifeandstyle #Dramafilms #Festivals #Worldnews #Culture #Belgium #Europe #Family #Film