an adjacent musician in the AFM local 802 directory to the one I was looking for listed his residence as the Gaylord Farm Sanatorium and I really had to look up what it was. since I can't afford a month in Indonesia this winter to cure my lung problems...

https://connecticuthistory.org/the-white-plague-progressive-era-tuberculosis-treatments-in-connecticut/

#tuberculosis

Large Tuberculosis outbreak strikes Kansas #kansas #TB #Tuberculosis #cartoon #gregkearney #kearney

Who received the Nobel Prize in 1905 for his work on tuberculosis?

A. Emil von Behring

B. Robert Koch

C. Paul Ehrlich

D. Ronald Ross

#nobelprize #tuberculosis #infection #science ... Continue to: https://www.facebook.com/1130092409221646/posts/1235475362016683

Is your #Amazon driver delivering #tuberculosis to you with that parcel? Learn more about the #sweatshop #poverty #disease which has killed more people than any other & its fascinating connection to #JeffBezos. #TB #PublicHealth #phthisis #vector https://www.ndtv.com/health/amazon-confirms-victorian-disease-outbreak-all-about-tuberculosis-spread-at-uk-warehouse-10781472

☣️ Amazon confirms outbreak of ‘Victorian disease’ at warehouse

#Tuberculosis #TB

https://www.unilad.com/news/world-news/amazon-tuberculosis-outbreak-warehouse-health-061539-20260117

It’s amazing that media has become so docile and subservient to corporate interests that they won’t print the word #tuberculosis in a headline…or even the top 5 paragraphs of a story on an outbreak in an Amazon warehouse.

https://www.unilad.com/news/world-news/amazon-tuberculosis-outbreak-warehouse-health-061539-20260117

Amazon workers at Coventry warehouse being tested for tuberculosis after possible outbreak https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2026/jan/16/amazon-workers-at-coventry-warehouse-being-tested-for-tuberculosis-after-possible-outbreak #Amazon #Tuberculosis #Health #Society #Internet #Ecommerce #UkNews

Medical advances have helped us prevent and cure tuberculosis, but the ancient bacterial disease still kills more humans than any other infectious pathogen. Researchers recently unveiled a device meant to demystify the early stages of TB, including a peculiar delay that often precedes the onset of symptoms. @ScienceAlert tells us more:

Scientists have made a discovery that helps explain why humans and animals are so susceptible to contracting #tuberculosis (TB) – and it involves the #bacteria harnessing part of the #immune system meant to protect against infection.

#Immunology #sflorg

https://www.sflorg.com/2026/01/imng01102601.html

Fight tuberculosis - obey the rules of health [between 1936 and 1941]

1 print on board (poster) : silkscreen, color ; 55.8 x 35.5 cm (board) | Poster promoting better health care through the prevention of tuberculosis by better eating and sleeping habits, and more exposure to sunshine.

#355cm #THERULESOFHEALTH #healthcare #color #posters #newyork #screenprints #newyork(state) #tuberculosis #photopgraphy #LibraryOfCongress

Me acuerdo

Me acuerdo de Perec se inspira en el libro de Joe Brainard en título, forma y espíritu pero he leído que esta forma de contar los recuerdos fue un género popular, a veces con sección propia, en los periódicos de los EEUU.

Me acuerdo de los chavales que hacían breakdance en la rotonda de las Esclavas. Llegaban cargando con un tronco de sintasol enrollado y el mejor casete que había visto en mi vida. Siempre había alguien que decía, imagino que retándolos, que no podían dar vueltas sobre la cabeza porque lo prohibieran por las muertes y otro que rosmaba, cuando empezaban a recoger, que aquello era gimnasia no baile.

Me acuerdo… no, en realidad no recuerdo nada del 23F aunque la mayoría de mi generación habla de que a pesar de su edad tienen un recuerdo muy vívido por no ir al colegio y la extraña programación de la televisión.

Me acuerdo cuando nos hacían la prueba de la tuberculina y como días después los positivos marchábamos juntos a Sanidad, cerca del Observatorio. Los otros niños nos llamaban tuberculosos y nosotros les pegábamos y les tosíamos en la cara. Aún conservo amigos de aquellas marchas: «Somos los tuberculosos, los que más, los que más nos divertimos…»

Me acuerdo que en 4º de EGB hicimos una biblioteca con libros de casa. Cada viernes una fila distinta de clase era la primera en escoger, los Super Humor eran los primeros que desaparecían. En aquella estantería metálica gris fue donde descubrí el mejor libro del mundo: «El zoo de Pitus», «El apoyo mutuo» para niños dispersos.

Me acuerdo las manualidades de rascar en un espejo las imágenes del Che o el Cristo de «Se busca» (como juraba con la corona de espinas). Después una persona mayor le tenía que aplicar el ácido y el rascador se tenía que alejar hasta el otro extramo de la habitación y perderse el milagro de la aparición.

#biblioteca #breakdance #ElZooDePitus #espejo #GeorgesPerec #MeAcuerdo #tuberculosis

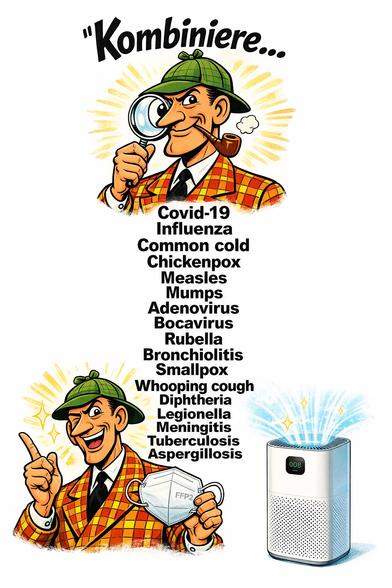

A #respiratorMask and #AirPurifier helps prevent all of these👇 #Covid19, #Influenza, #CommonCold, #Chickenpox, #Measles, #Mumps, #Adenovirus, #Bocavirus, #Rubella, #Bronchiolitis, #Smallpox, #WhoopingCough, #Diphteria, #Legionella, #Meningitis, #Tuberculosis, #Aspergillosis

#FYI #USA #MicrobeTV #ThisWeekInVirology #DanielGriffin #VincentRacaniello #MASA #MakeAmericaSaneAgain #infectiousdiseases #vaccinate #vaccines #pertussis #whoopingcough #tetanus #measles #tuberculosis #influenzaA #RSV #influenza #covid19 #covid #sarscov2 #LongCovid #mushrooms #mushroompoisoning

#TWIV 1284 clinical update week 03. Jan. 2026

Today's quote: "The role of the infinitely small in nature is infinitely great" Louis Pasteur

Tina Hesman Saey: Funding chaos may unravel decades of biomedical research. Current actions open the door for future administrations to put their political stamp on higher #education.

#tuberculosis #medicine #health #TB #trump

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/trump-harvard-funding-biomedical

Vaccine protests are not new in Toronto and the GTA. You can read the charts. We also need to bring back the isolation hospitals. The one shown here is now called Riverdale Hospital. Conveniently located near the Don Jail it housed some of the overload. Also some of the mental misfits.

#antivax #vaccines #riverdale #hospital #tuberculosis #measles #chickenpox

Research Scientist I, Pisu Lab

Tulane University

Research Scientist driving Mtb studies using CRISPR, NGS, flow cytometry, microscopy, BSL2–BSL3 pathogen work, macrophage models, and murine infection

See the full job description on jobRxiv: https://jobrxiv.org/job/tulane-university-27778-research-scientist-i-pisu-lab/

#CRISPRscreen #immunology #macrophage #singlecellanalysis #tuberculosis #ScienceJ...

https://jobrxiv.org/job/tulane-university-27778-research-scientist-i-pisu-lab/?fsp_sid=7144

Five big global health wins in 2025 that will save millions of lives https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2025/dec/22/five-big-global-health-wins-in-2025-that-will-save-millions-of-lives #Globaldevelopment #Medicalresearch #Cervicalcancer #Globalhealth #Tuberculosis #AidsandHIV #Society #Malaria #Health #MMR

Post-Doctoral Fellow, Pisu Lab

Tulane University

Postdoc in macrophage heterogeneity and Mtb infection using murine/NHP models, CRISPR, multiomics, flow cytometry, and BSL3 research.

See the full job description on jobRxiv: https://jobrxiv.org/job/tulane-university-27778-post-doctoral-fellow-pisu-lab/

#CRISPRscreen #macrophage #singlecellanalysis #tuberculosis #ScienceJobs #hiring #research

https://jobrxiv.org/job/tulane-university-27778-post-doctoral-fellow-pisu-lab/?fsp_sid=7088

Protect her from tuberculosis Consultation of your doctor or clinic means prevention. [between 1936 and 1938]

1 print on board (poster) : silkscreen, color ; 55.9 x 35.6 cm (board) | Poster promoting regular medical checkups for prevention of tuberculosis, showing woman holding a flower.

#356cm #tuberculosis #women #healthcare #newyork(state) #health&welfare #screenprints #color #posters #photopgraphy #LibraryOfCongress

Laboratory Supervisor I, Pisu Lab

Tulane University

Lab Supervisor role leading Mtb and macrophage research using CRISPR, multiomics, flow cytometry, BSL3 work, and mouse infection models.

See the full job description on jobRxiv: https://jobrxiv.org/job/tulane-university-27778-laboratory-supervisor-i-pisu-lab/

#crispr #CRISPRscreen #macrophage #singlecellanalysis #tuberculosis #ScienceJobs #hiri...

https://jobrxiv.org/job/tulane-university-27778-laboratory-supervisor-i-pisu-lab/?fsp_sid=7025

![The image is a vintage poster with bold graphic design elements that aim to raise awareness and encourage preventive measures against tuberculosis. It features an illustration of a woman's face in profile, rendered in yellow tones on a black background, suggesting she may be asleep or at rest. Above her head are stylized representations of lungs, highlighted by yellow radiating lines, symbolizing the focus on respiratory health.

The poster has prominent text in capitalized letters with varying font sizes and styles to emphasize key points: "FIGHT TUBERCULOSIS" is displayed prominently across the top half in large red lettering. Below this, a smaller directive reads "OBEY THE RULES OF HEALTH," which appears as if it's commanding attention from the viewer.

A significant portion of text below states "THE RULES OF HEALTH", and at the bottom left corner, there's an acknowledgment or attribution to YPA Federal Art Project [1935-42], indicating that this poster was created during a time when art projects were commissioned by federal programs aimed at public service announcements.

Overall, the design is intended to be strikingly visual while conveying important health messages.](https://files.mastodon.social/cache/media_attachments/files/115/862/280/383/255/849/small/32ca8db3d70b7abb.jpeg)