There is, at the time of this writing, an ongoing debate in the Crypto Research Forum Group (CFRG) at the IETF about KEM combiners.

One of the participants, Deirdre Connolly, wrote a blog post titled How to Hold KEMs. The subtitle is refreshingly honest: “A living document on how to juggle these damned things.”

Deirdre also co-authored the paper describing a Hybrid KEM called X-Wing, which combines X25519 with ML-KEM-768 (which is the name for a standardized tweak of Kyber, which I happened to opine on a few years ago).

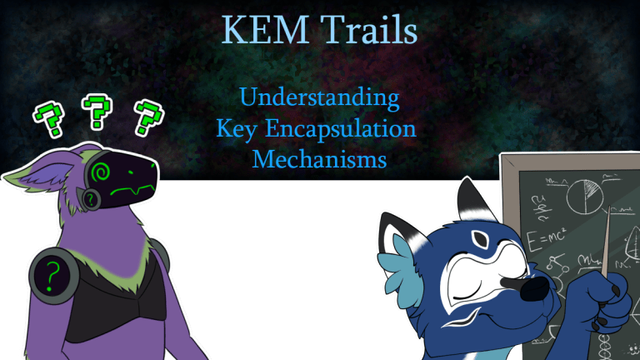

After sharing a link to Deirdre’s blog in a few places, several friendly folk expressed confusion about KEMs in general.

So very briefly, here’s an introduction to Key Encapsulation Mechanisms in general, to serve as a supplementary resource for any future discussion on KEMs.

You shouldn’t need to understand lattices or number theory, or even how to read a mathematics paper, to understand this stuff.

CMYKat Building Intuition for KEMs

For the moment, let’s suspend most real-world security risks and focus on a simplified, ideal setting.

To begin with, you need some kind of Asymmetric Encryption.

Asymmetric Encryption means, “Encrypt some data with a Public Key, then Decrypt the ciphertext with a Secret Key.” You don’t need to know, or even care, about how it works at the moment.

Your mental model for asymmetric encryption and decryption should look like this:

interface AsymmetricEncryption { encrypt(publicKey: CryptoKey, plaintext: Uint8Array); decrypt(secretKey: CryptoKey, ciphertext: Uint8Array);} As I’ve written previously, you never want to actually use asymmetric encryption directly.

Using asymmetric encryption safely means using it to exchange a key used for symmetric data encryption, like so:

// Alice sends an encrypted key to BobsymmetricKey = randomBytes(32)sendToBob = AsymmetricEncryption.encrypt( bobPublicKey, symmetricKey)// Bob decrypts the encrypted key from Alicedecrypted = AsymmetricEncryption.decrypt( bobSecretKey, sendToBob)assert(decrypted == symmetricKey) // true

You can then use symmetricKey to encrypt your actual messages and, unless something else goes wrong, only the other party can read them. Hooray!

And, ideally, this is where the story would end. Asymmetric encryption is cool. Don’t look at the scroll bar.

CMYKat Unfortunately

The real world isn’t as nice as our previous imagination.

We just kind of hand-waved that asymmetric encryption is a thing that happens, without further examination. It turns out, you have to examine further in order to be secure.

The most common asymmetric encryption algorithm deployed on the Internet as of February 2024 is called RSA. It involves Number Theory. You can learn all about it from other articles if you’re curious. I’m only going to describe the essential facts here.

Keep in mind, the primary motivation for KEMs comes from post-quantum cryptography, not RSA.

CMYKat From Textbook RSA to Real World RSA

RSA is what we call a “trapdoor permutation”: It’s easy to compute encryption (one way), but decrypting is only easy if you have the correct secret key (the other way).

RSA operates on large blocks, related to the size of the public key. For example: 2048-bit RSA public keys operate on 2048-bit messages.

Encrypting with RSA involves exponents. The base of these exponents is your message. The outcome of the exponent operation is reduced, using the modulus operator, by the public key.

(The correct terminology is actually slightly different, but we’re aiming for intuition, not technical precision. Your public key is both the large modulus and exponent used for encryption. Don’t worry about it for the moment.)

If you have a very short message, and a tiny exponent (say, 3), you don’t need the secret key to decrypt it. You can just take the cube-root of the ciphertext and recover the message!

That’s obviously not very good!

To prevent this very trivial weakness, cryptographers proposed standardized padding schemes to ensure that the output of the exponentiation is always larger than the public key. (We say, “it must wrap the modulus”.)

The most common padding mode is called PKCS#1 v1.5 padding. Almost everything that implements RSA uses this padding scheme. It’s also been publicly known to be insecure since 1998.

The other padding mode, which you should be using (if you even use RSA at all) is called OAEP. However, even OAEP isn’t fool proof: If you don’t implement it in constant-time, your application will be vulnerable to a slightly different attack.

This Padding Stinks; Can We Dispense Of It?

It turns out, yes, we can. Safely, too!

We need to change our relationship with our asymmetric encryption primitive.

Instead of encrypting the secret we actually want to use, let’s just encrypt some very large random value.

Then we can use the result with a Key Derivation Function (which you can think of, for the moment, like a hash function) to derive a symmetric encryption key.

class OversimplifiedKEM { function encaps(pk: CryptoKey) { let N = pk.getModulus() let r = randomNumber(1, N-1) let c = AsymmetricEncryption.encrypt(pk, r) return [c, kdf(r)] } function decaps(sk: CryptoKey, c: Uint8Array) { let r2 = AsymmetricEncryption.decrypt(sk, c) return kdf(r2) }} In the pseudocode above, the actual asymmetric encryption primitive doesn’t involve any sort of padding mode. It’s textbook RSA, or equivalent.

KEMs are generally constructed somewhat like this, but they’re all different in their own special, nuanced ways. Some will look like what I sketched out, others will look subtly different.

Understanding that KEMs are a construction on top of asymmetric encryption is critical to understanding them.

It’s just a slight departure from asymmetric encryption as most developers intuit it.

Cool, we’re almost there.

CMYKat The one thing to keep in mind: While this transition from Asymmetric Encryption (also known as “Public Key Encryption”) to a Key Encapsulation Mechanism is easy to follow, the story isn’t as simple as “it lets you skip padding”. That’s an RSA specific implementation detail for this specific path into KEMs.

The main thing you get out of KEMs is called IND-CCA security, even when the underlying Public Key Encryption mechanism doesn’t offer that property.

CMYKat IND-CCA security is a formal notion that basically means “protection against an attacker that can alter ciphertexts and study the system’s response, and then learn something useful from that response”.

IND-CCA is short for “indistinguishability under chosen ciphertext attack”. There are several levels of IND-CCA security (1, 2, and 3). Most modern systems aim for IND-CCA2.

Most people reading this don’t have to know or even care what this means; it will not be on the final exam. But cryptographers and their adversaries do care about this.

What Are You Feeding That Thing?

Deirdre’s blog post touched on a bunch of formal security properties for KEMs, which have names like X-BIND-K-PK or X-BIND-CT-PK.

Most of this has to deal with, “What exactly gets hashed in the KEM construction at the KDF step?” (although some properties can hold even without being included; it gets complicated).

For example, from the pseudocode in the previous section, it’s more secure to not only hash r, but also c and pk, and any other relevant transcript data.

class BetterKEM { function encaps(pk: CryptoKey) { let N = pk.getModulus() let r = randomNumber(1, N-1) let c = AsymmetricEncryption.encrypt(pk, r) return [c, kdf(pk, c, r)] } function decaps(sk: CryptoKey, c: Uint8Array) { let pk = sk.getPublickey() let r2 = AsymmetricEncryption.decrypt(sk, c) return kdf(pk, c, r2) }} In this example, BetterKem is greatly more secure than OversimplifiedKEM, for reasons that have nothing to do with the underlying asymmetric primitive. The thing it does better is commit more of its context into the KDF step, which means that there’s less pliability given to attackers while still targeting the same KDF output.

If you think about KDFs like you do hash functions (which they’re usually built with), changing any of the values in the transcript will trigger the avalanche effect: The resulting calculation, which is not directly transmitted, is practically indistinguishable from random bytes. This is annoying to try to attack–even with collision attack strategies (birthday collision, Pollard’s rho, etc.).

However, if your hash function is very slow (i.e., SHA3-256), you might be worried about the extra computation and energy expenditure, especially if you’re working with larger keys.

Specifically, the size of keys you get from ML-KEM or other lattice-based cryptography.

That’s where X-Wing is actually very clever: It combines X25519 and ML-KEM-768 in such a way that binds the output to both keys without requiring the additional bytes of ML-KEM-768 ciphertext or public key.

From the X-Wing paper.

However, it’s only secure to use it this way because of the specific properties of ML-KEM and X25519.

Some questions may come to mind:

- Does this additional performance hit actually matter, though?

- Would a general purpose KEM combiner be better than one that’s specially tailored to the primitives it uses?

- Is it secure to simply concatenate the output of multiple asymmetric operations to feed into a single KDF, or should a more specialized KDF be defined for this purpose?

Well, that’s exactly what the CFRG is debating!

CMYKat Closing Thoughts

KEMs aren’t nearly as arcane or unapproachable as you may suspect. You don’t really even need to know any of the mathematics to understand them, though it certainly does help.

I hope that others find this useful.

Header art by Harubaki and AJ.

https://soatok.blog/2024/02/26/kem-trails-understanding-key-encapsulation-mechanisms/

#asymmetricCryptography #cryptography #KDF #KEM #keyEncapsulationMechanism #postQuantumCryptography #RSA