The thread about Hawkhill, its House and the marvellous things that once went on there

If old gate piers could talk, they could tell many a tale of who once passed through them, could they not?

There’s an old gate pier on Lochend Road. What would it tell us if it could? Would it have interesting tales to tell? Shall we find out?

So why is there a Georgian gate pier leading to 1980s housing? Well of course there used to be a Georgian house here before there were 1980s houses. Given this area is known as Hawkhill, the house was sensibly called Hawkhill House. The name Hawkhill is descriptive and literal – there was once a hill here were hawks must have dwelled. It’s mentioned as Halkehill in 1560, and shown as Halkhill in Adair’s map of 1682.

“Halkhil” on John Adair’s Map of Midlothian, 1682. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandOnce part of the Barony of Restalrig, these lands found their way into the possession of Lord Balmerino after the Logans were dispossessed of them. He in turn lost them – and his head – for his part in the Jacobite rising of 1745. The Crown gave (or sold) them on to Trinity College & Hospital, who feud a small estate of 20 acres off of them at Hawkhill in the 1750s.

Outline of the Hawkhill lands on Roy’s Lowland Map, c. 1750. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe feuar was Andrew Pringle, Lord Alemoor, a judge, senator of the College of Justice, Solicitor General for Scotland and a Lord of Session. “He had an unrivalled reputation as a lawyer and pleader“. He was the son of John Pringle, Lord Haining of The Haining in Selkirkshire, who also was a respected judge and one time Senator of the College of Justice.

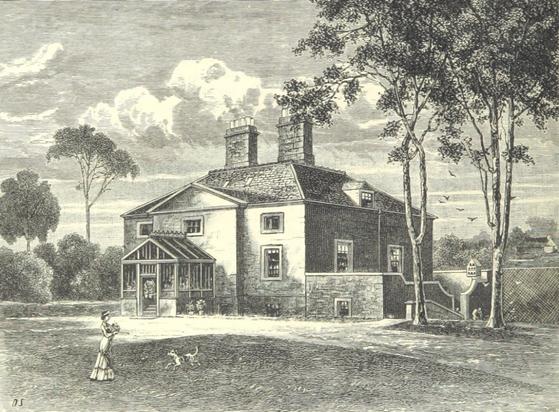

Andrew Pringle, Lord Alemoor, by William Brassey Hole. CC-by-NC National Galleries ScotlandAlemoor had John Adam, son of William and older brother to Robert and James, build him a small but perfectly formed villa on the land. Overshadowed as an architect by his younger brothers, John was more involved in the business administration, but was nevertheless a fine and competent architect. Hawkhill was squat but perfectly formed, topped with two large and distinctive chimneys.

Lord Alemoor’s Villa at Hawkhill near Edinburgh by John AdamA later description from its sale notes:

“two lofty and finely-proportioned public rooms, library, five bedrooms, two dressing rooms, hot and cold baths, large kitchen, laundry, and other accommodation is supplied… There is a lodge for the gardener; stable, coach-house and other offices which are all ample; also a high-walled garden, well stocked and productive, and a large greenhouse. There is about 2 and a half acres of detached garden ground, bounded for 400 yards on the north side by a high wall planted with good fruit trees. The remainder of the property consists of a park of about 10 acres, and the shrubberies, in which there are some fine old trees.”

A description of Hawkhill in 1867

Alemoor was a man of letters. Sir Adam Ferguson took James Boswell to sup with him at Hawkhill. The latter was reportedly left impressed. He was “a very spirited and successful improver” and kept a fine garden, planted a good stock of trees and had a large parkland for sheep. But after the law, Alemoor’s main passion was science. He was supported in this by his factor, James Hoy. He had an observatory erected on the top of the Hawkhill to the latest designed by John Smeaton. We can see it and the house poking out in a late 18th century watercolour

Hawkhill, the observatory and the house in the distance, beyond Lochend house and Doocot. From the Hutton Papers vol. 2. CC-BY-SA 4.0 National Library of ScotlandAlemoor had Hoy take and keep regular, accurate temperature records for 7 years. Hoy kept this practice up at Castle Gordon where he went next to work and his data set was used to help calculate the first accurate, average temperature for Scotland. On June 4th 1769, Alemoor, Hoy and Dr James Lind (of investigations into scurvy and tropical medicine fame) observed the transit of Venus across the sun, each using a different telescope and each keeping time accurately. The Astronomer Royal commended their results as particularly accurate. This was an event of major world scientific importance – Captain James Cook had been sent all the way to Tahiti to observe it – and perhaps the first “crowd-sourced” scientific endeavour?

Excerpt from Dr James Lind’s letter to the Astronomer RoyalExcerpt from Dr James Lind’s letter to the Astronomer RoyalAlemoor died in 1776, the house passing to his brother who likely sold it to pay of their fathers’ debts on the home estate of The Haining. It came into the possession now of Captain Gideon Johnstone, RN. Gideon had been a captain at the Battle of Chesapeake Bay in 1781 but never got another command again after that. He retired to Hawkhill, dying there in 1788. The house passed to his brother John Johnstone of Alva, “a corrupt Nabob of the East India Company“.

John Johnstone esq. of Alva, right, by Henry Raeburn. Miss Wedderburn is centre, here niece Betty Johnstone on the left.Johnstone went to India as a clerk, avoided the “Black Hole of Calcutta” which claimed his brother and found himself as an artillery officer. He worked his way up to being a provincial governor but returned from India in a scandal, fired by his former friend General Clive on the subject of taking bribes from local princes. He therefore came back overshadowed but fabulously rich, so retired to a quiet life as a country gentleman of leisure on the estate of Alva.

Hawkhill was given to his niece, Elizabeth – Betty – Johnstone, on the left in the painting above. She was the youngest sister of Margaret Johnstone, Lady Ogilvy, who was sentenced to death after the ’45 for her part in encouraging her husband in his support of the rising. He fled to France and she did the same, escaping Edinburgh castle by swapping clothes with her washer woman and walking out the gate. Aunt Betty was unmarried but doted on by her nieces. They took Aaron Burr to visit her, who wrote in his diary “Pretty place. View of the Forth.” he noted he had a sumptuous meal and Madeira wine. This would be about 1808. Who was Aaron Burr? He was an America lawyer and politician, 3rd Vice President of the United States. He is noted for having “assassinated” Alexander Hamilton (former Secretary of the Treasury) in a duel in 1804. He was in Europe on a self-imposed exile.

Aaron Burr by John Vanderlyn, 1802Betty died of old age at Hawkhill in 1813. She passed away during a thunder storm, looking to the sky and remarking “Sirs, what a night for me to be fleeing through the air” before expiring. She is buried with the Fergusons of Pitfour, also of her family, in Greyfriars. Hawkhill went to her cousin, James Raymond Johnstone esg. of Alva, who had inherited John Johnstone’s estate and ill gotten fortune from India. He gave it in life rent to his sister Ann Elizabeth and her husband James Gordon of Craig, an Advocate.

Hawkhill as it was in the mid 19th century, much the same as Georgian times except the added conservatory. Note the trees, sunken garden to the right. Perhaps Ann Elizabeth Johnstone strolling in the foreground. From Old & New Edinburgh vol. 5 by James GrantAnn Elizabeth died at Hawkhill in 1851, at which point the whole estate was put up for sale. The advert noted that the lands had value in quarrying and felling the trees planted by Alemoor.

The Scotsman, March 10th 1852The lands were now split up. The hill of Hawkhill itself began to be quarried for its whinstone for use in street paving setts. Alemoor’s trees were felled and his sheep park was dug up for clay to feed a brickworks built on the site. Worse was to come when a tallow melting works was built in the eastern portion of the park land. The works belonged to Alexander Beveridge of Leith; “margarine manufacturer and tallow melter, employing 17 men and 13 women” and a member of The Incorporation of Candemakers of Edinburgh.

A brick from the Hawkhill Brickworks, found in the Warriston Cemetery © SelfThe reek from the tallow works and dust from the quarrying both ended up in court cases from disgruntled neighbours. The “Tallow Melting Case” found in favour of the works, and the works and the stench went on.

Scotsman, 1866Thomas Field, “slate merchant, brick and tile maker and quarry master” lost his case and the brickworks was ordered to shut; quarrying went on however. In 1877, three boys were hospitalised in Leith after playing with blasting powder from the quarry. A young woman working in the Tallow Works lost an arm to machinery in 1877 in horrible circumstances.

Scotsman, 17 Sep 1883The site of the closed brickworks was sold off and became the Hawkhill Recreation Fields, a commercial enterprise. It was used for amateur sports, professional football, dog racing, as a showground and fairground. Then on 1 October 1888 something quite incredible happened at Hawkhill…

At 5:15PM, the slight figure of “Professor” James Baldwin strode across the field, packed to capacity. In one hand he had a “parachute umbrella” in the other he took hold of a trapeze suspended from a hot air balloon. Then the balloon was let go…

“DROP FROM CLOUDLAND” advert, from the Scotsman, September 1888The balloon rose quickly to 1,200 feet and Baldwin let go of the trapeze. He fell 300 feet before opening his “umbrella”. He fell to the ground, landing gently and exactly where he wanted to.

BALDWIN’s DROP FROM THE CLOUDS. © British LibraryBaldwin was a circus acrobat, tightrope walker and all round daredevil with a keen interest in ballooning. This was a trick he had first performed the year before in the US and he had brought it to Europe. It was a sensation and he made a fortune.

“Baldwin’s Drop from the Clouds”, poster advert for London in 1888Baldwin made the first ever parachute jump in the US in 1887. In 1888 he made the first in the UK. The Houses of Parliament were suspended in order that members could go see for themselves before deciding whether or not to ban his act as suicidal. On the 1st October 1888, he made the first parachute jump in Scotland at Hawkhill.

London Illustrated News illustration of Baldwin’s act.Such was the popularity of the act, that Hawkhill exceeded capacity. The proprietor of the next door farm at Lochend, Fanny Jackson, successfully sued Baldwin’s organisers for £30 for damages done to gates, fences and crops by the crowds who invaded her farmland. Ten years later on July 5th 1899, a balloon jumper act returned. This time it was Miss Alma Beaumont, “Lady Parachutist” who leapt from the skies as part of a huge show and fair put on at Hawkhill to coincide with the Highland Show.

Scotsman advert, July 4th 1899Alma Beaumont. Via Yeovil Virtual MuseumIn 1890, a balloon was flown from Edinburgh International Exhibition at Meggetland and came down safely at Hawkhill grounds.

The 1890 Edinburgh International Exhibition at MeggetlandFrom 1888 to about 1900, Hawkhill House itself was used as a residential boarding house, run by “Mrs Donaldson, late of Wooton Lodge, Cumin Place, the Grange“. By 1902 it was owned by Jonathan Newey & Sons, who ran a firelighter manufacturing business on the site. The quarry was worked out by about 1913, having completely consumed the Hawk Hill in the process (in case you’re wondering where it went as it’s quite clearly no longer there). In 1924, Leith bakers J. Smith & Sons built a modern, industrial bakery there. It later became part of the Sunblest empire.

Edinburgh Evening News, 17 October 1924The recreation grounds were bought after WW1 by the Leith Education Authority for use as school and public playing fields. Amateur football was allowed to continue, but professional sport and dog racing was banned. They continued to let the park out for sheep grazing. In 1920 they came into possession of the Edinburgh Education Authority, who tendered for “100 carts of good black soil” to be delivered to improve the playing fields. Many a local school, scouts and amateur sporting event would take place there over the next 70 years. When Leith Academy moved it its new site, it got on-site playing fields (“Academy Park”), and Hawkhill Fields were sold off for housing. Alemoor Crescent and Park were built, recalling the house’s first Laird, Andrew Pringle.

The tallow melting works closed in 1968, taking its stench with it, and was replaced by the council housing “multis” of Hawkhill Court and Nisbet Court (the Nisbets of Craigentinny were an old local landowning family, but never actually of Hawkhill.)

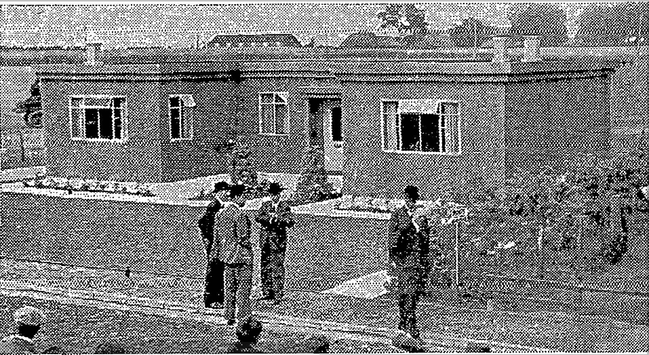

Hawkhill Court and Nisbet Court, 1977, © Edinburgh City LibrariesHawkhill House by this point was unoccupied but remarkably much of its original John Adam Georgian interiors were still in place, if somewhat decrepit. The Georgian Society campaigned to preserve it.

Survey photos of Hawkhill House for the Ministry of Works, 1966. From Canmore’s entry for Hawkhill House.But it deteriorated further and was soon bricked up not long after that photo study, it is looking very sad in the photo below taken in the early 1970s, not long before it was demolished in (I think) 1972. The site was added to the playing fields.

Hawkhill House, early 1970s. Unknown provenance (I’ve looked for it!)We can see 130 years of transition at Hawkhill in this animated overlay of maps.

Animated map transition of Hawkhill, 1817 to 1944. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandBefore finishing, I’d like to just say thanks to the ever helpful and knowledgeable Fergus Smith for the quick lesson (late) last night about how property could, or could not be, inherited in Scotland before 1868. It really helped me with this and saved a lot of time in working out some of the ownership. Thanks Fergus!

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#Adams #Ballooning #Enlightenment #Lawyers #Lochend #Science #Written2022