Warum machen Menschen Dinge, die sie eigentlich nicht wollen oder im Nachhinein zutiefst bereuen? Wie funktioniert dieser Mechanismus der Manipulation? Wie agieren Sekten und toxische Gemeinschaften? Diese Fragen werden von der neuen Folge von #Wiewirticken beantwortet:

👉 https://www.ardaudiothek.de/episode/urn:ard:episode:409b16e5aee1b015/

#ARD #ARDAudiothek #Podcast #Deutschland #Sekte #Sekten #Seelenfänger #Yoga #Psychologie #Manipulation #gaslightning #Scientology #Lovebombing #Kult #spiritualbypassing #ToxicPositivity #coercivecontrol

#coercivecontrol

@feather1952 @MarkAsser I have a friend (much younger than 80) who was a victim of coercive control. Her soon to be (officially) ex-husband took control of her debit card, telling her he was paying her share of the bills with it. He drained her account and, even after she left him, she found out that he had set up direct debits from her account to pay his bills. She had never authorised these. Now, living away from him in a rural town, she goes into the local bank and withdraws enough cash for the week over the counter. She is adamant that she will never use cards or internet banking ever again.

#CoerciveControl #Cash

The purpose of a system is what it [does] enables: Smart cars being used for coercive control and domestic abuse: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-12-01/smart-cars-used-as-weapons-by-domestic-violence-abusers/106079588

#domesticviolence #coercivecontrol #smarttechnology #POSIWID

"In one example several years ago, a woman's car had a "kill switch" activated that prevented her from driving beyond a 1 kilometre radius from her home."

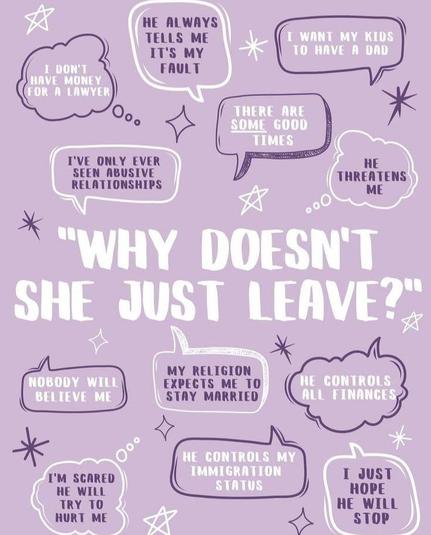

If someone stays in an abusive relationship, it’s not because they’re weak —

it’s because the abuser made leaving terrifying, impossible, or deadly.

💬 Survivors need support, not shame.

#YouAreNotAlone #DVSurvivor #TraumaBonding #CoerciveControl #SafetyFirst #ListenAndBelieve #CompassionOverJudgment 💜🕊

London, 2025 — Rolleiflex 2.8D; Tri-X, red filter.

You tried to turn me into a Dahlia—pretty, parted, forgettable; I answered with a Shelley left on the table, a record that refused your silence and named what omission built.

© Morgan Gardner

#rolleiflex #trix400 #noir #coercivecontrol #london

Ammanford man jailed for controlling behaviour and assaults in Tenby and London

Assaults in Tenby holiday let

Jack Griffiths, 23, of High Street, Ammanford, appeared at Swansea Crown Court where he admitted multiple offences committed in both west Wales and London.

The court heard that on 17 May this year, Griffiths assaulted his partner and another man at a holiday let in Tenby. When police were called to the address, he also attacked an officer.

Prosecutor Alycia Carpanini told the court Griffiths had subjected his partner to a campaign of controlling and coercive behaviour between October 2023 and May 2024. He dictated what she ate, who she spoke to, and even what she was allowed to watch on television.

Violence in London

Griffiths also admitted three separate assaults in the London Borough of Haringey on 30 November 2023, where he attacked three men.

Guilty pleas and sentencing

Griffiths pleaded guilty to:

- Engaging in controlling or coercive behaviour

- Two counts of assault occasioning actual bodily harm

- Assault by beating of an emergency worker (Tenby offences)

- Two counts of assault by beating

- One further count of assault occasioning actual bodily harm (London offences)

Judge Huw Rees sentenced him to a total of three years and nine months in prison.

Griffiths’ ex‑partner was also granted a 10‑year restraining order to protect her from further contact.

Earlier proceedings

The case was first heard at Haverfordwest Magistrates’ Court in May, where Griffiths faced charges of coercive control, intentional strangulation, and multiple assaults. He was remanded into custody before being committed to Swansea Crown Court for sentencing.

Georgia Barter's Death Ruled Unlawful Killing Due to Domestic Abuse and Coercive Control

Georgia Barter, 32, died from a drug overdose in April 2020, after years of domestic abuse by her partner, Thomas Bignell. An extraordinary ruling by a London coroner found her death to be an unlawful killing, caused by the coercive control and violence she endured from Bignell. Despite her reports ... [More info]

Man sentenced for seven years of abuse and coercive control over partner

Antonio Villafane, also known as Anthony Manson, has been found guilty of coercive control, strangulation, unlawful wounding, actual bodily harm, and fraud after a seven-year period of abuse towards his partner, Sally Ann Norman. The couple met in 2015 and lived an off-grid lifestyle in a caravan ne... [More info]

Societies and institutions keep on normalising male #violence and #femicide

#CoerciveControl #Men

https://masscasualtycommission.ca/files/documents/Phase-2-Written_FFF-PANST.pdf

Dyfed‑Powys and South Wales Police buck national decline in coercive control charges

Local forces top the table

Almost ten years after coercive and controlling behaviour (CCB) was made a criminal offence under the Serious Crime Act 2015, new analysis shows that Dyfed‑Powys Police and South Wales Police are leading the way nationally in bringing charges.

- Dyfed‑Powys Police saw the biggest rise in England and Wales, with the proportion of offences leading to a charge or summons more than doubling from 4.05% to 8.65% in the past year.

- South Wales Police recorded the second‑highest increase, climbing from 10.11% to 11.16%.

By contrast, many other forces saw their charge rates fall, with the City of London dropping to zero and Nottinghamshire and Wiltshire also recording sharp declines.

What coercive control means

Coercive control covers patterns of intimidation, isolation, financial restriction and emotional manipulation. It was recognised in law in 2015 to reflect the reality that abuse is not always physical, but can still have devastating and long‑lasting effects.

Family law specialists say the rise in charges in Wales may reflect more victims feeling able to report abuse, but also highlights the scale of the problem.

“Statistics only tell part of the story”

Kathryn McTaggart, family law solicitor and director at Woolley & Co, said:

“Clients often describe years of financial restriction, emotional manipulation, or social isolation – behaviours that don’t just end when the relationship does. They continue to shape how safe someone feels during separation, whether they can engage in mediation, and the tone of negotiations.”

She warned that while criminal prosecutions show progress in some areas, the family courts remain inconsistent. Allegations of coercive control are often raised in divorce, child contact and financial disputes, but the way courts respond can vary dramatically.

What it means for families in Wales

- In divorce cases, coercive control is increasingly cited in petitions, but survivors often feel the abuse is invisible in financial settlements.

- In child contact disputes, courts are expected to investigate allegations before making decisions, but practice varies widely.

- In financial proceedings, the law sets a high bar for conduct to affect asset division, leaving many survivors feeling the economic impact of abuse is overlooked.

Campaigners say that without consistent recognition across both criminal and family courts, survivors remain at risk of being retraumatised by the very systems meant to protect them.

ITV Wales presenter Ruth Dodsworth has spoken out about her experience of coercive control after her ex‑husband was jailed for harassment and abuse.(Image: Regan Talent Management)

Ruth Dodsworth: speaking out after coercive control conviction

ITV Wales presenter Ruth Dodsworth has become one of the most high‑profile voices raising awareness of coercive control after her ex‑husband, Jonathan Wignall, was jailed in 2021 for a near‑decade campaign of harassment and abuse.

Since then, Ruth has spoken publicly about the impact of coercive control on her life and family, using her platform to encourage survivors to seek help and to press for stronger safeguards in both the criminal justice system and the family courts.

Related articles

- Maesteg man jailed after subjecting teenager to years of coercive control

- Long prison sentence for vile Swansea man who raped and controlled women

- ‘Immature’ Aberavon man jailed following controlling and abusive behaviour

Ruth Dodsworth: Speaking out on coercive control

ITV Wales presenter Ruth Dodsworth has spoken publicly about her experiences of coercive control after her ex-husband, Jonathan Wignall, was jailed in 2021 for a near-decade-long campaign of harassment and abuse.

Since the case, Ruth has become a prominent voice in raising awareness of domestic abuse, sharing her story to encourage others to seek help and to highlight the importance of safeguarding.

- TV presenter’s ex-husband jailed after near decade-long campaign of harassment and controlling behaviour

- ITV’s Ruth Dodsworth talks about her experiences of domestic abuse in support of National Safeguarding Week

#abuse #coerciveAndControllingBehaviour #coerciveControl #criminalCourt #divorce #DyfedPowysPolice #emotionalManipulation #familyCourt #familyLaw #financialRestriction #harassment #intimidation #isolation #law #relationships #RuthDodsworth #SeriousCrimeAct #socialIsolation #SouthWalesPolice

Legal Abuse in California Family Courts: Ethical Divorce Law

Author(s): Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Publication (Outlet/Website): The Good Men Project

Publication Date (yyyy/mm/dd): 2025/05/27

Padideh Jafari, founder of Jafari Law & Mediation Office, shares over two decades of family law experience, emphasizing her ethical stance against legal abuse. She discusses the emotional and financial toll of high-conflict divorces, especially when clients weaponize the legal system. Attorney Jafari highlights her firm’s vetting process, refusal to represent unethical behaviour, and the importance of therapy in cases involving narcissistic traits. She explains systemic challenges in California’s family court system and her passion for advocating for vulnerable clients. Beyond law, she maintains emotional balance through horseback riding, mental health days, and her rescue dog. Lastly, she also offers insight and guidance for aspiring women lawyers.

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: Today, we are joined by Padideh Jafari who is the founder and CEO of Jafari Law & Mediation Office, with over 22 years of experience in family law. She is a leading voice against legal abuse—when clients weaponize the legal system to harm ex-spouses through prolonged litigation and manipulation.

Padideh Jafari: Thank you for having me.

Jacobsen: Attorney Jafari is known for her ethical integrity, often walking away from cases when ethics cross the line. She speaks candidly about how economic pressures compromise attorneys, the ethical dilemmas in high-conflict divorces, and the urgent need for systemic reform. Her insights are essential for understanding the intersection of legal ethics, family court, and client-driven abuse.

I have one quick question on the side—something I was thinking about. When do you feel a case has crossed the line? Or is there a specific example that illustrates when you, based on your ethical standards, decide not to take or continue with a case?

Attorney Jafari: Our firm has a clear vetting process, especially early on. We avoid representing individuals who present with Cluster B personality disorders—such as narcissistic personality disorder or borderline personality disorder—unless they are under appropriate psychiatric care and treatment. The reason is that such individuals often complicate the divorce process for their soon-to-be ex-spouse and their own attorney.

They tend to be high-conflict and difficult to manage. They may send excessive emails, text messages, or calls during weekends, disrupting boundaries and creating emotional chaos. These are not the types of clients we aim to work with.

Additionally, when someone seeks to switch attorneys—commonly referred to as “subbing out” their previous counsel—we request full documentation and context from the former attorney. We need to understand why the client leaves one lawyer to hire another. In many high-conflict cases, the client fires the attorney after not hearing what they want. Then, they move to a new attorney who becomes a “saviour” for a short time—until the cycle repeats.

They do not want resolution; they want to perpetuate conflict. Eventually, they fire the new attorney as well. It’s less about strategy and more about maintaining emotional control and chaos. They may continue this cycle multiple times.

Let me give you an example. A couple of years ago, I saw a litigant—on the opposing side—who had gone through seven attorneys in just eighteen months. That was not our client, but it illustrates the situation we try to avoid at all costs. At our law firm, we are committed to ethical representation. We aim to offer thoughtful, solution-oriented legal services—not to enable conflict or dysfunction.

Attorney Jafari: California’s family law is somewhat black and white. It is a 50/50 community property state. But there are gray areas, and that’s where we advocate for our clients—working within those gray areas to find solutions. We do not want to be used as pawns in the sick game of hurting spouses. That is not what our law firm wants to be known for.

Jacobsen: Something that people do not often talk about—at least not as openly as other forms of abuse—is legal abuse. The concept is more familiar in professional circles, such as among psychologists or clinicians. In public discourse, however, physical abuse and sexual abuse are more easily discussed. Subtler forms like emotional, psychological, financial, or legal abuse are still newer to mainstream awareness. They are not new to practice—in law, psychology, or clinical settings—but they are newer to public vocabulary.

So, when we look at a technical definition of legal abuse, what does that imply? And conversely, what is something that may seem like legal abuse but is not?

Attorney Jafari: I do not know if you know, but California has now codified coercive control.

Jacobsen: I did not know that.

Attorney Jafari: You can look up the legal definition of coercive control. It captures the emotional abuse through legal abuse that you’re referring to. The challenge is that although California—and some other states—have codified coercive control, lawyers and judges have not fully embraced the law yet. It is still very new.

To me, legal abuse is when someone—whether it’s our client or the opposing party—files legal documents knowing they have no merit, purely to force their ex or soon-to-be ex-spouse to defend against them. Whether it’s a motion, discovery request, or any other filing, the intent is to overwhelm or financially exhaust the other party. That is legal abuse.

Now, if there’s even a 10% chance that a claim is legitimate, that is not legal abuse. There must be a clear absence of merit and an intent to harass or intimidate.

Some law firms—particularly in Southern California—have developed a reputation for what is called churning. Churning divorce cases, unfortunately, is quite easy, especially when children are involved. There’s so much at stake, and emotions run high. You might be dealing with allegations of physical abuse, domestic violence, or other complex issues.

It’s why people refer to personal injury attorneys as “ambulance chasers.” Divorce attorneys have their stereotype: sharks. There’s a perception that we are here to break couples apart—that we love divorce. Unfortunately, a subset of divorce attorneys reinforces that perception. They profit from conflict because if people do not get divorced, those attorneys do not make money.

But there is another kind of divorce attorney—those here to offer real solutions. We work with our clients and opposing counsel to reach a workable solution. I hesitate to say “win-win” because, in divorce, it rarely feels like anyone is truly winning. However, we aim for a resolution both parties can live with, especially when children are involved.

When there are no children, it is generally easier—California is a community property state, after all. But when there are kids, emotions rise and fall, and things become far more complex.

So, I would define legal abuse as filing motions or discovery requests that have no merit. It’s Family Code Section 6320, as amended in 2021 by Senate Bill 1141.

Jacobsen: So, in the context of divorce and family law, how does legal abuse play out? Can these cases drag on for years, or is this the kind of abuse that usually peters out within a few months?

Attorney Jafari: Oh, it can last for years. Unfortunately, legal abuse can persist in the long term. The longest case I have seen lasted 12 years. It was in Downtown Los Angeles. One party would file for discovery, the other would not respond, and the cycle would be repeated.

This was a case involving a celebrity client. Their daughter aged out during the litigation—she turned 18—so custody was no longer at issue. But the fighting continued. The client refused to settle. Her husband would make settlement offers, and she initially agreed, saying, “Yes, I’ll take it.” Then, two days later, she would call back and say, “I think I should get more.”

It reached the point where the judge retired, and a new judge took over the case. The new judge looked at the case file and asked, “What is happening here?” It was a perfect illustration of legal abuse.

You and I can chuckle about it in person, but when you think about it—do these people want to resolve their financial issues now that their child is an adult? The answer is no. People who want resolution will often settle, even if they receive less than they believe they deserve because they value their mental health more than continued litigation.

At one point, I told the client, “Do you want to live in the courthouse? Because you’re here more than I am.” And yes, I have seen legal abuse stretch on for years.

Unfortunately, judges in Southern California often do not put a stop to it. Even in the case where the opposing party had gone through seven different attorneys, every time we went to court, I would say, “Your Honor, this is a new attorney. It’s costing my client more attorney’s fees to bring this person up to speed.” But the response was essentially, “It is what it is.” The judge was not saying that, but that was the attitude.

Then, that judge moved to a different department, and we had yet another new judge come in. So yes, legal abuse is real, and it can take years.

Jacobsen: How do you stop it?

Attorney Jafari: The truth is—it’s difficult. It might be easier in other jurisdictions or states, but I can only speak for California where I practice, and it is not easy.

Even if you raise the issue of legal abuse with the judge, the response might be, “Well, it’s the clients who are perpetuating it. If they agree, I’ll sign off on it.” So, it is not necessarily the judge’s fault. Sometimes, judges will order a Mandatory Settlement Conference—an MSC—to try and force both sides to resolve the case.

But I have seen MSCs continue for months. And then you’re back in court, hearing the same stories, with the same circus. One side says, “I’m not ready for the MSC.” The judge asks, “How much time do you need, Counsel?” They say, “I don’t know… ninety days?” Then, ninety days pass, and the other side asks for a continuance. It becomes a cycle.

Meanwhile, the client is asking, “What do I do?” And the answer is: settle. Settle for less than you think you deserve—because if you want it to be over, that is how you regain some control. These cases can go on and on, and they are not cheap.

Jacobsen: These cases are not free—they cost a lot of money. So, are we typically dealing with people from a higher professional strata? Or someone who happened to come into a significant inheritance? How are people affording this? Are there cases where, due to some legal technicality, one party is forced to fund both sides—creating a dynamic where they mutually abuse each other and drag the case out for up to twelve years?

Attorney Jafari: All of the above. It can be someone working and genuinely believing in their case, believing it’s about principle. They’ll say, “I must do this because it’s the principle.” But unfortunately, the law is not concerned with your principles. And those cases can take years because people remain emotionally invested.

They could also be individuals who received an inheritance. Of course, here in Los Angeles County, we represent a number of celebrities who have their own independent income streams.

Then, there’s the situation where a judge orders one party to pay the other’s attorney’s fees. In that twelve-year case I mentioned earlier, that’s exactly what was happening. The husband was a celebrity, and we’d return to court every couple of months to request more attorney’s fees. He was funding both his legal team and hers.

But I will tell you this—it continues until the money runs out. When the stock market is doing well, and home values are rising, we often see cases where a property is sold, and the proceeds go into a client trust account. One of the attorneys manages the account, and we might agree: “Okay, each attorney gets $25,000 from the trust.”

But when that money is depleted, suddenly, the conversation changes. Clients begin to realize, “Wait a minute—I’m not even going to walk away with anything from the equity in my house.”

That’s when we sit with our client and say, “You can stop this. You can stop the bleeding.”

The best-case scenario is when both parties come to that realization. They see their monthly legal bills and say, “I don’t want to keep paying for this.” Then they go to their attorney and say, “I’m done.” And the attorney responds, “Great. Here’s a workable solution we can settle on.”

Now, since we operate in a high-conflict area of family law, we do encounter cases involving narcissists or individuals with Cluster B personality disorders—people who fundamentally do not want to settle.

So the question becomes: how do you resolve those cases?

Once again, we tell our clients to take less than what they think they’re owed. The goal is to end the debt.

Jacobsen: Are there emotional strategies you recommend in those cases? For example, certain white lies—emotionally flattering statements directed at the opposing party, who may display narcissistic traits or a full-blown Cluster B personality disorder. I’m thinking of using a combination of flattery and compromise—taking a little less than what the client thinks is justified—to bring the case to a close and get their life back. Is that something you counsel clients to do?

Attorney Jafari: Absolutely. It might sound counterintuitive, but in some situations—especially when the opposing party is narcissistic—you can get further by saying something like, “You’re such a good father,” or, “I appreciate how involved you’ve been.” It may not be how the client feels, but it’s a strategic concession while not quite flattery. It helps the other party feel validated and resolves the case.

We explain to clients that it’s not about fairness anymore. It’s about freedom. Sometimes, you need to take a bit less and say what needs to be said—not because it’s entirely true, but because it allows you to walk away and live your life.

I don’t know if I would call it flattery. I tend to say, “You catch more bees with honey.” I have even said—just as an analogy—”If you need to bake cupcakes for the person, why do you care?” That’s just an example, of course.

There are some people, Scott, who have been abused in the relationship or the marriage, and they do not want to give anything. They do not want to see this person get away with anything. For them, it becomes about principle. But, as I said before, the law is not about principle.

So yes, I have coached clients to resolve the matter—even if it means taking a little bit less—by whatever means are available. I have arranged four-way meetings with the other side, where we sit together in an office and ask, “How can we resolve this?”

Sometimes, face-to-face interaction helps. When I started practicing in 2002, that’s all we did. There was no Zoom, no constant texting. I still hold onto that old-school mentality where, when you’re sitting in front of someone, it’s harder to say “no.”

That kind of meeting lets you say, “Let’s try to make the best out of this situation—for both clients.” And sometimes, you can reason with the opposing attorney in that setting.

That approach does not always work, but it is worth trying. Sometimes, issues do not get resolved in the first meeting. Then we say, “Let’s take two or three weeks, give it some space, and revisit.” Then, you hold a second meeting, and some issues may finally be resolved.

In Southern California, about 95% of cases settle before trial because trial is extremely expensive. It can cost anywhere from $25,000 to several hundred thousand dollars.

So these cases usually resolve before trial—but how you get there, especially with high-conflict individuals, is another matter entirely. It can still take years.

Jacobsen: What you describe sounds like a pressure valve release—a de-escalation tactic. At the same time, it also serves as a release valve for the emotional pressure your client is enduring. Do you ever feel sorry for both parties? Do you ever find yourself watching two people go in circles—over an issue that should have been resolved individually—and realize the court is now functioning more like couples therapy for two people who are no longer a couple?

Attorney Jafari: That is a fair question. Twenty-two years ago, when I was much younger, I had more of an emotional response to these situations. But now, I am much more stoic.

I look at it this way: this couple got married. They were—hopefully—in love with each other. They said vows in front of family and friends. And now they are getting divorced. I try to understand the psychology behind how they got to this point.

But do I feel sorry for them? What I feel is a sense of duty—how can I best advocate for my client.

And sometimes that also means advocating for the other side. You’re acknowledging that the other side is suffering as well, right? It is not like they are sitting there completely happy. These are deeply emotional situations.

That’s why I bring both parties together in a meeting and say, “How can we resolve this?” I want to look at them and say, “Look, I’m not here to hurt you. That’s not my intention as your spouse’s attorney.”

But at the same time, I am bound by what my client instructs me to do. I can only act within those limits. So I say, “Let’s try to resolve this. Let’s find a way forward.”

Now, I do get emotional in cases involving child molestation or rape. A separate division of our law firm handles those cases. I get emotional about those—I have sleepless nights, moments of outrage, and a range of reactions. Those cases stay with you.

But with the more typical divorce matters, I’ve developed more emotional distance over the years. After 22 years, you’ve seen almost everything.

Jacobsen: I think we mentioned the horse farm in our last interview. I might be misremembering, but there was an older lawyer woman—not saying her name, of course—who was well past retirement age but was not retiring. A few times, she would come to the horse farm, and people asked, “Is she okay?”

By then, there had been a few signs that something was off. She did not connect well with clients or staff those days, not often. But on those days, she would stay with her horse, enter the indoor arena, ride, and quietly leave. I remember thinking, “That’s the tail end of something.”

Do you change your tone with clients in moments like that? You mentioned being stoic—but what kind of linguistic wizardry do you employ at Hogwarts Legal Abuse, Inc.?

Attorney Jafari: [Laughing] Are you asking generally or specifically in high-conflict cases?

Jacobsen: We do not have time to discuss this in-depth, but I mean broadly—what general principles do you apply in your speech and presentation?

You will not speak to me like you’d speak to a distraught client. You’ll be dressed professionally, calm, and composed. Outside of those exceptional cases, you’ll be stoic but adjust your tone, pace, and inflection. You’re using your knowledge of the case to convey a sense of stability and safety. Then, you do what your practice is built to do: propose solutions.

So, what does that communication strategy look like?

Jafari: I’d love to say I always have it perfectly under control, but that’s not the case. And anyone in this profession should not pretend otherwise. As divorce attorneys, we must be extremely careful about what we say because our clients hang on to every word.

We work in high-conflict divorce. Most of the time, we represent the “innocent” spouse. Not innocent in the absolute sense—everyone has ups and downs in a marriage—but innocent in the sense that they are not the abuser.

They are not the narcissist. They are not trying to hurt their spouse. They are victims of narcissistic abuse or domestic abuse. So yes, 100%, the way we talk to them—our tone, our language—matters deeply.

At the same time, we also have to be extremely firm. I do not sympathize to the point of being seen as a “girlfriend”figure. That can happen, especially when you have a female attorney and a female client. Those boundaries can blur quickly if you are not careful.

So, it is very important to establish healthy boundaries from the beginning. I’ll advocate fiercely for my clients and clarify: “No, you cannot have my cell phone number. No, you cannot text me on weekends—unless it is a true emergency.” That kind of clarity is essential.

And I speak from experience. Twenty-two years ago, I was a young attorney early in my career. You want to connect and commiserate with your clients, but over time, I learned that it does not help them. It blurs the lines and can disempower both the client and the attorney. Boundaries are critical.

Some clients, Scott, do not even know what boundaries are—especially if they have come out of abusive marriages.

Jacobsen: Oh yes, I completely understand.

Attorney Jafari: When someone has spent years in an abusive relationship, they may interpret a firm boundary as being mean or even abusive. And I have to explain, “No, this is not about rejecting you. This is about setting a healthy boundary—for both of us.”

That is when I usually suggest therapy. A good therapist will help teach boundary work if nothing else. And I tell clients, “You do not have to go to therapy forever. Even if you go for three or seven sessions while the divorce is active, it can make a huge difference.”

When they hear that, they feel some relief. It feels manageable. I have had clients come back and say it was the best thing they did for their mental health. It helped them make better decisions and finally move forward—rather than staying stuck in the abuse.

Jacobsen: Yes. When someone is of sound mind and in healthy circumstances, the present moment is clearer, boundaries are intuitive, and decisions are grounded. But for people who have been tortured or raised in abusive families, that clarity can be shattered. Their perceptual boundaries are skewed. Whether it is a journalist, therapist, or lawyer, they’ll often project a lot unconsciously.

Certain themes always emerge in those cases, and that’s very apt. Before we wrap up, I want to note one other thing. When we last spoke in December, around Christmas, you mentioned launching a podcast. How is that going?

Attorney Jafari: Yes! The podcast is now in Season Two. It is another valuable resource I recommend to my clients. I tell them to go to The Narcissist Abuse Recovery Channel on Spotify or Apple Podcasts and listen to the episodes.

We also have an Instagram account—@narc.podcast—where we post supportive content. It helps clients know that I understand what they are going through, even if I do not disclose my own experiences during our meetings. This builds trust. They see that their attorney gets it—and that I can help guide them out of it if they’re willing to listen and take the advice.

If they go off and do their own thing—or want to make it about principle—that’s a separate issue. They’ll end up stuck in the court system, which I call the hamster wheel. You’ll return every month or every two to three months, just showing up repeatedly.

The judge will be there—that’s their job—and you’ll keep showing up, too. That’s what the hamster wheel is. I can help you get out of it, but it will take time, patience, and a willingness to listen to the advice of your counsel.

Jacobsen: What happens when people don’t take that key advice? Do they end up back on the hamster wheel? Or is it worse—like they made a bad decision, and the situation has escalated?

Attorney Jafari: I’ve seen it get worse. Clients who take things into their own hands and ignore their attorney’s advice often complicate the situation.

I’ve seen the attorney file a substitution of attorney to remove themselves from the case entirely. The client will then say, “Why are you doing this? You’re abandoning me!” But the attorney thinks, “Look, I’ve given you every possible tool, and you’re ignoring all of it.”

I always give my clients this visual: “You and I are standing on the ninth floor of a building. If you jump, I’m not jumping with you.” I will stand beside you, advocate for you, tell you what the law is, negotiate for you, and do everything I can within my professional boundaries.

But if you decide to jump—meaning, to make reckless or emotional decisions against legal advice—then you’re on your own. And I think that is how most divorce attorneys feel. It’s a pretty accurate visual representation of the role.

Jacobsen: That seems like a fundamental life lesson for a lot of people—not just about getting information from open-source tools, like your podcast or social media, but also about understanding that tailored legal advice is there for a reason. The decision is theirs—and they have to own it.

Attorney Jafari: Yes, it’s ultimately their decision and impacts their life—and, in many cases, their child’s life, too.

If you do not have children, then it’s your life alone. You can make mistakes and live with the consequences. But when you have children, your decisions affect more than just you. You must think long-term about whether there’s a custody dispute or anything related to the child.

And Scott, it’s not like it was 22 years ago. Children today learn everything. They have access to social media, online court records, and public files.

I’ve had a child reach out to me and say, “Can you get me my parents’ divorce file?” And I said, “Absolutely not.” But the reality is that it’s public. They can go look it up themselves if they’re of age. That’s the world we’re living in.

So yes, it’s hard. But bringing in the right professionals—like a good therapist who understands divorce dynamics—makes a huge difference. Especially if you believe you’re divorcing a narcissist.

And I always clarify: only a licensed mental health professional can diagnose narcissistic personality disorder. But yes, people can display narcissistic traits.

Attorney Jafari: So it’s not necessarily full-blown narcissism, but rather narcissistic traits. In those cases, you need a therapist to guide you through the emotional aspect and your attorney to guide you through the legal aspect.

Jacobsen: Is it only on Apple Podcasts, or is it on Spotify too?

Attorney Jafari: It’s also on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Jacobsen: What’s the tension between the duty to advocate and the responsibility to act ethically?

Attorney Jafari: First and foremost, ethics. That always comes first. I am obligated to the California State Bar—the governing entity—and I feel a personal moral and ethical obligation to myself. And then third, I have an obligation to the client.

There are law firms that will take on any divorce client without going through the kind of vetting process I mentioned earlier. Then, they eventually realize the client is difficult or in conflict. These clients go from attorney to attorney, subbing one out after another—and that’s when you see the hamster wheel pattern emerge.

For us, ethics matter deeply. That’s why we work with fewer clients. Not everyone who walks into our office is accepted. And it’s interesting—some people get angry when we decline a client. They say, “Now I want you to represent me.” And you’re thinking, “There are plenty of attorneys down the street.” But no, they want you, specifically, because they know you have strong boundaries and won’t compromise—and yet, paradoxically, they want you to operate in that gray area anyway.

I’ve had that happen. And we’ve had to withdraw from those cases. Those are tough conversations to have. You must tell the client, “You’re asking me to do something unethical, and I’m not going to do it.”

It’s easy to say that to you, Scott. But it is hard to say it to a client, especially when emotions are running high. They’ll ask, “What do you mean?” And I’ll reply, “Here are ten examples of how you want me to ‘advocate’ for you—but that’s not true advocacy. What you’re asking for is misuse of the legal system.”

The law is meant to be a shield—not a sword. But they want me to act as a sword, and I am only willing to act as a shield.

Jacobsen: Are there some cases where that shield is so important to you that you will take on the case pro bono?

Attorney Jafari: We take on pro bono cases a few times a year. Sexual abuse of minors, for instance—those cases are incredibly important to me.

When I worked for the District Attorney’s Office, I was assigned to a unit called Stewart House. It’s still in existence in Santa Monica, California. They specialize in child molestation and rape cases. The DAs work closely with the parents and prosecute the offenders. Unfortunately, many of those cases do not go to trial because children under 18 are often deemed incompetent to testify.

I interned at Stewart House for three months between my first and second years of law school, and that experience shaped me. So when cases like that come into our office—where one parent has molested or raped the child, and now that same parent is asking for visitation rights—I take them seriously.

Sadly, in California, parental rights are often prioritized over the child’s rights. Unless those rights are formally terminated or the District Attorney prosecutes and obtains a conviction, that parent may still be granted visitation. It is a heartbreaking legal reality.

I’m passionate about those types of cases. In some of those, the firm may do pro bono work. But generally speaking, if it’s a standard divorce case without such egregious circumstances, we do not handle it pro bono.

Jacobsen: So through this, the City of Santa Monica agreed in April 2023 to pay $122.5 million to settle claims involving 24 individuals who alleged they were sexually abused as children by Eric Uller—a former city employee and volunteer with the Police Activities League. He was arrested in 2018 on multiple molestation charges and died by suicide later that year. So, in cases like that, they run through Stuart House?

Attorney Jafari: Yes.

Jacobsen: For those who may not know much about the legal context in the United States—it’s a free country, so you get extremes. There’s more variance in legal applications compared to more centralized systems.

You might have the Convention on the Rights of the Child, but in these cases, parental rights can often supersede that Convention regarding U.S. legal interpretation or application, right?

There are still cases where child marriage laws are lacking or other protections aren’t fully enforced. This kind of thing has happened often—though it often escapes attention.

Attorney Jafari: Yes.

Jacobsen: When do you feel emotionally exhausted as a lawyer working in a “high-conflict” law system?

Attorney Jafari: Wow—that’s a question nobody asks me. I don’t know if anyone besides my husband truly cares—because he doesn’t want an emotionally exhausted wife.

It is not easy. Twenty-two years later, I am still trying to find that balance. I do have hobbies, one of which is horseback riding. I’ve taken up becoming an equestrian over the past year. Spending time with animals is incredibly grounding.

The thing about animals is—they love you unconditionally. You can talk to them as much as you want or not at all. And they understand your silence. That’s one thing that helps me.

I also adopted my dog, who came from the Los Angeles Wildfire Rescue. He is a licensed emotional support animal, but to be honest, he supports me more than he supports our clients, so that has helped me a lot.

Jacobsen: He has a side gig in the emotional law department.

Attorney Jafari: Yes! [Laughing]

I would say the cases involving sexual abuse are by far the most emotionally draining. That’s where I feel it most intensely.

I also take mental health days. If I feel like I’ve reached a limit—where my brain does not want to operate anymore—I’ll take a half day off or a full day if possible. That does not happen often—there’s always something going on at the firm—but I’ll say to myself, “Tomorrow is a mental health day,” and I mean it.

Because what happens with divorce attorneys is that we think about our cases after 6 p.m., we think about them on weekends, and we think about them on vacation. So when I declare a mental health day, it’s a promise to myself that I will not think about any cases.

I’ve found three things helpful: horseback riding, adopting my rescue dog, and mental health days. They’ve been essential for my well-being.

Jacobsen: Quick advice for women just starting in divorce law? They could be interning at Stuart House or entering their first or second year of law school—or maybe even in the final year or two.

Attorney Jafari: It’s important to realize why you want to pursue the profession of law. I knew why I wanted to pursue it—since I was five, I wanted to be a lawyer. I know we talked about that during our first interview. I’ve always known my “why.”That has been essential.

It’s important to figure that out early on because once you’re done with law school, you’ll either find a job at a firm or start your own. At that point, you don’t get to stop and ask yourself those foundational questions.

For me, it was clear. I’ve had that passion since I was five. When I needed to step back from practice for a while, I taught at NYU. You can do many things with a law degree, opening up many paths. But for me, it’s always been about my passion for my clients and the drive to advocate for the underdog—the person who cannot speak up for themselves or doesn’t have a voice. Seeing them on the other side of that journey—free from abuse, free from the toxic relationship—that freedom and peace are incredibly rewarding to witness.

I also know for a fact that there are now more women in law school than men. When I heard that statistic, I was excited. It’s a great field for women. Women, by nature, are nurturing. They want to see justice prevail. So, it’s a great profession for women.

And within the law, there are so many different areas. Not everyone can be—or wants to be—a divorce attorney, and I respect that. But law is still a noble profession. No matter what anyone says, it’s noble. People who aren’t lawyers don’t understand what we do, so it’s easy to judge. But only another lawyer really knows what it takes.

So, it is a noble profession for anyone who wants to pursue law.

Jacobsen: My last question is purely self-indulgent—just something for the equestrian in me. So, regarding your type of riding, are you doing show jumping, dressage, or three-day eventing? What’s your discipline? Please tell me it’s not a three-day event. I’m hoping.

Attorney Jafari: [Laughs] English. I’m taking English riding lessons.

Jacobsen: Excellent.

Attorney Jafari: Eventually, I’d like to do jumping, but I’m not there yet. That will take a couple of years.

Jacobsen: When you get to the meter-sixties, let me know. We’ll see you on the American show jumping team.

Attorney Jafari: [Laughing] Sounds good. Sounds good, Scott.

Jacobsen: Thank you so much for your time today.

Attorney Jafari: Thank you so much, Scott. It’s great to see you.

Jacobsen: Great to see you, too. And congratulations on your dog and your horsey.

Attorney Jafari: Thank you so much!

—

For more information: https://www.jafarilegal.com/team/padideh-jafari-orange-county-family-attorney/.

Last updated May 3, 2025. These terms govern all In Sight Publishing content—past, present, and future—and supersede any prior notices. In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons BY‑NC‑ND 4.0; © In Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen 2012–Present. All trademarks, performances, databases & branding are owned by their rights holders; no use without permission. Unauthorized copying, modification, framing or public communication is prohibited. External links are not endorsed. Cookies & tracking require consent, and data processing complies with PIPEDA & GDPR; no data from children < 13 (COPPA). Content meets WCAG 2.1 AA under the Accessible Canada Act & is preserved in open archival formats with backups. Excerpts & links require full credit & hyperlink; limited quoting under fair-dealing & fair-use. All content is informational; no liability for errors or omissions: Feedback welcome, and verified errors corrected promptly. For permissions or DMCA notices, email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com. Site use is governed by BC laws; content is “as‑is,” liability limited, users indemnify us; moral, performers’ & database sui generis rights reserved.

#CoerciveControl #EthicalAdvocacy #FamilyLaw #LegalAbuse #NarcissisticTraits

Child’s death drives churches to call out coercive control and cult-like behaviour

How did one man convince 13 other people to let an eight-year-old girl die? This is the question…

#NewsBeep #News #Headlines #antivaxxer #AU #Australia #brendanstevens #christian #coercivecontrol #compass #Crime #cult #diabetes #elizabethstruhs #pastor #pentecostal #Queensland #Religion #religious #thesaints

https://www.newsbeep.com/50575/

It’s not the beliefs that are the focus, it’s the strategies used to coerce & control.

Using this framing I can’t help but think of the way children - & all of us - are acculturated into gendered scripts. These can be enforced so brutally & do so much harm. They scar us for life. As do ideas of racial & cultural hierarchy for that matter. Maybe hierarchy, power (esp entitlement to define) & control ARE the problem?

Thank you to the state of Victoria for conducting this enquiry into the recruitment methods and impacts of cults and organised fringe groups. And to all the brave survivors of coercive practices, for speaking out.

#CoerciveControl #cults #acculturation #healing #victoria #ResponsibleGovernance

Despite some high profile successes in the prosecution of partners for coercive control, it appears (once again) many police forces are not getting it right on the ground - prosecuting the victims of conceive control for the actions they have bene forced into, rather than going after the perpetrators.

I'd like to say this is surprising, but its all too grimly predictable!

DARVO in action

Deny

Attack

Reverse Victim/Offender

#CoerciveControl #GasLighting

RE: https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:cnpe7qvcyjrhm6w7w7e4atur/post/3lud3wge2bc2q

Immer, wenn Täter Opfer attackieren, werden Opfer verdächtigt, sich selbst in die Lage gebracht zu haben und es evtl. sogar zu genießen. Das ganze Scheinwerferlicht scheint aufs Opfer, das verdächtigt wird, an der Täter-Tat Schuld zu sein.

Und der Täter grinst im Dunklen während die Flying Monkeys ihn befeuern. Uh uh ah ah.

What is this, homo sapiens sapiens? Und wann verlernen wir das endlich?

#CoerciveControl

#Abuse - all kinds of -

#Empathie

In Queensland, Australia kannst du jetzt bis zu 15 Jahre im Gefängnis landen, wenn du #CoerciveControl und #NarcissisticAbuse gegen deine Kinder, Partnerinnen oder Mitarbeitenden ausübst.

In Deutschland gehört es zur weit verbreiteten Leitkultur und Mentalität.