Bước vào thế giới kỳ quái của "Eraserhead" - bộ phim kinh điển của David Lynch. Câu chuyện theo chân Henry trong một thị trấn công nghiệp u ám, nơi thực tại đen tối hòa quyện với siêu thực. Đây là trải nghiệm không thể bỏ lỡ cho những tín đồ điện ảnh! #Eraserhead #DavidLynch #KinhDị #GiảTưởng #PhimKinhĐiển https://ift.tt/Foi0DLG

#Eraserhead

🎶 "Stompin' the Bug" - Thomas 'Fats' Waller 🎵

https://youtube.com/watch?v=I0jSEuZTMd4

#portland #oregon #pdx #pnw #photos #photography #mobilephotography #digitalphotography #smartphoneography #iphoneography #iphone #shotoniphone #editedoniphone #nocleanuptool #noai #fediverse #pixelfed #citylife #city #urban #theater #theatre #theaters #theatres #hollywood #hollywoodtheatre #cinema #movies #films #motionpictures #silverscreen #davidlynch #thomasfatswaller #fatswaller #ost #eraserhead

MHA Vigilantes Episode 2:

Oh I guess it’s going to be Vigilantes every time then… that’s kind of disappointing… it is a cool title card still… all right I’m just not even gonna question that… whoa they totally just skipped over the whole “this is me you’re probably wondering how I got here moment after all huh… not even a midpoint break moment either…

#Anime #animeandmanga #manga #myheroacademiavigilantes #myheroacademia #MHA #SogaKugisaki #eraserhead #eraserheadMHA

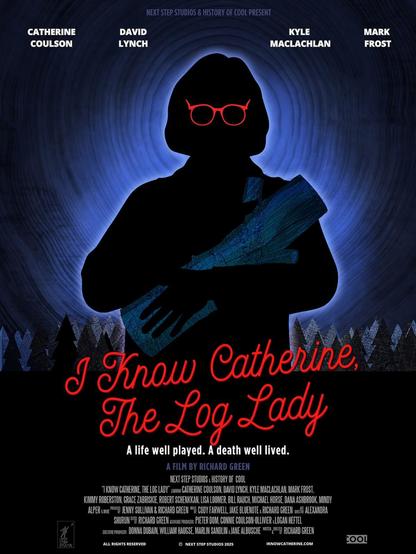

I Know Catherine, The Log Lady – The Lynchian documentary opens this week. Trailer and details here https://bit.ly/4jdjTQE

#CatherineCoulson #IKnowCatherineTheLogLady #film #documentary #DavidLynch #MarkFrost #KyleMacLaclan #TwinPeaks #Eraserhead

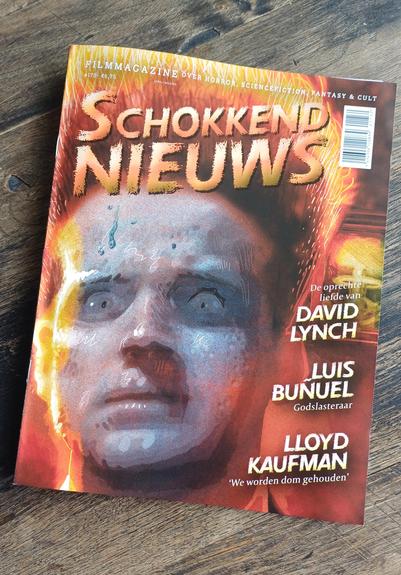

Maar helemaal tof met een uitgebreide ode aan Lynch en zo'n fantastische cover van Milan Hulsing 🔥🔥

#schokkendnieuws #schokkendnieuwsfilmmagazine #davidlynch #lynch #eraserhead #milanhulsing #moviemagazine #horror #sciencefiction #fantasy #cult

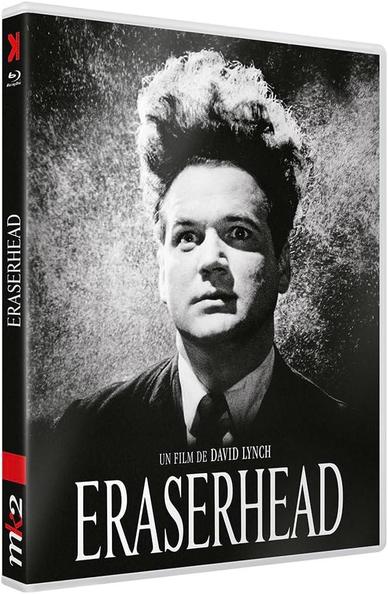

Voilà, j'ai tenu parole. J'ai acheté le blu-ray de #Eraserhead. Plus qu'à trouver la motivation pour le regarder... 😏

If you live in the #SFBA & are a #MovieFan &, whether you know it or not, are a fan of #film #screenplays written and/or direct by David Lynch, check out the retrospective of his work which is going to be shown at the #RialtoCinema in #ElCerrtio in the coming week or so:

https://rialtocinemas.com/coming-soon-cer/david-lynch-retrospective-cer/

Among the movies that will be shown are: #LostHighway, #BlueVelvet, #MullhollandDr, #InlandEmpire, #ElephantMan, #EraserHead, #Dune (1984) & #wildatheart

Quite a few #ClassicMovies among them. I'm planning to go to watch Dune & Blue Velvet.

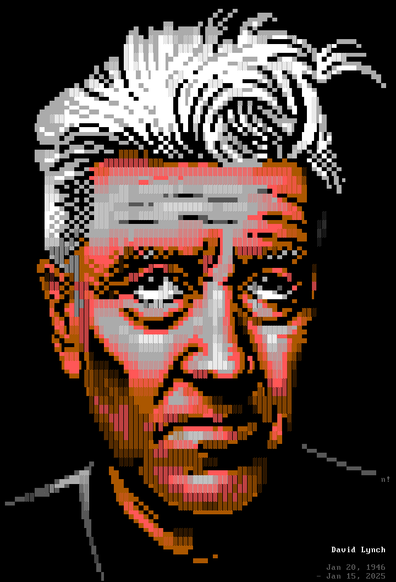

In honor of David Lynch (1646 - 2025)

#eraserhead #henryspencer

#characterdesign #illustration #adobeillustrator #corelpainter #illustratoronmastodon

Grieving David Lynch

By Cody Lakin.

What do you do with the grief for a person you didn’t know?

When I saw the first headline about David Lynch’s passing, I stood as if paralyzed, unable to accept it as truth. A quick Google search led me to the slew of headlines that cemented the news as reality. I became extremely aware of my own breath and my own heart’s beating, and sat down, wilting with the beginnings of a grief more complicated than I ever could’ve anticipated.

Everyone who knows his work has a story of their first encounter. Mine was with Mulholland Drive (2001), the film that began production as a television pilot—and one of so many examples across Lynch’s career of doubt and interference from executives. After it was turned down by executives, Lynch later wrote an ending for the story and filmed new material for it, shaping it into a feature film.

I’d been working at an independent movie rental store called Couch Critics in my hometown of Mount Shasta, California, a job that was singularly responsible for informing and refining my taste in art and storytelling. At a certain point, I went through a thankfully brief phase of bigheadedness about my own so-called expertise in cinema. I was discovering filmmakers who are still deeply important to me, but I was overly certain of myself and my assessments of film, having little notion of the type of cinema I would later discover that would radically rearrange my view of the possibilities of art.

One such seismic discovery was David Lynch. At the time, no film had ever pissed me off to the degree that Mulholland Drive did. Here was a film that refused any conventional logic in plot or character. Here was a film that felt as much like a dream as like a nightmare, seeming to use a sometimes pedestrian aesthetic to settle you into a false sense of security. There’s much debate about what the term Lynchian actually means, but I might not be remiss to approach it by describing how Lynch’s work sometimes plays upon a specific Americana aesthetic, one that can seem idyllic, charming, pedestrian, even campy, while a savage, hungry, incomprehensible darkness lurks just underneath, not merely in the story but in how the visual style of his films adapts to fit what they depict. Like with Twin Peaks, the normality present in much of Mulholland Drive merely amplifies its encroaching yet ever-present darkness. Like a nightmare that wears the mask of a pleasant dream.

I lost sleep over that film. Why did it feel so impenetrable? Why didn’t it offer at least some clearer clues to its meanings? What the hell had I just watched and why couldn’t I get it out of my head? If you had asked me, then, what I’d thought of it, I might’ve said, simply, “I hate Mulholland Drive.” Yet there was something about it I couldn’t shake, an admiration for its audacity, a sense of begrudging awe. After all, I’d truly never seen anything like it.

After reading those initial articles about Lynch’s passing, I went to work at the bookstore and shared the news with my managers and coworkers. One of my coworkers came in later that day—another lover of film and specifically of David Lynch—and we hugged and talked about our reactions to the news. He spoke about the tears he shed, and we agreed to meet in a few nights to watch Inland Empire (2006). With every passing conversation I had that day with every customer, I felt something like a gulf in me. Anyone familiar with the fresh sense of loss may understand. Questions that occur to you, like, “How is the world just going on as normal?”

That evening after returning home from work, I played a few of my favorite YouTube videos about David Lynch; compilations of interviews, behind-the-scenes footage, conversations with his film family of actors, actresses, and composers, and snippets from his occasional lectures on meditation, art, and the creative process. These were videos I’d been returning to throughout the years, having always found Lynch’s personality a surprising mixture of funny, inspiring, and wholesome. He spoke so clearly about creativity; his familiarity with that abstract, mercurial landscape was apparent, as was his passion for it. For someone capable of creating some of the most unsettling and disturbing films I’d ever seen, I never ceased to be surprised by how wonderful a human being he was.

Watching those videos in the immediate wake of his passing, it occurred to me how automatic my appreciation of David Lynch had been for a long time, nearly to the point I felt I’d taken it for granted. He had been a curiously big part of my life ever since first experiencing his work, and I was only feeling the gravity of that connection fully now, in the beginnings of mourning. There are countless examples of Lynch refusing to elaborate on the meanings of his work; there are just as many clips of him championing his collaborators, raging against imposed limitations on the creative process, and urging everyone to abandon the idea of suffering as a necessity to create meaningful art. These videos—mainstays in my life—made me laugh and made me feel inspired. Now there was a new dimension to them. A melancholy, but a comfort.

Years later, when I think of Mulholland Drive, the emotions are just as strong but they’re a different shade. I was a young, quietly arrogant person back then. That was one of the first films I can describe as a humbling experience. It flattened any sense of intellectual understanding in favor of a more intuitive understanding, something I had very little experience with at the time. It was the type of work that made me reevaluate what it means to engage with a piece of art. Art isn’t always palatable or beautiful; it isn’t always there to simply be admired or understood. The French filmmaker, Robert Bresson, is one of the earliest examples I’m aware of of a filmmaker who was vocal about the hope that viewers would rather feel his films than understand them. This is one of the key things, I discovered, with engaging a work from David Lynch. If you can let go of the need to understand it, there will be a deeper sense of understanding, an emotional one. An understanding in your heart.

In the years since that first encounter, I’ve seen nearly all of his films, including the entirety of Twin Peaks multiple times. Some of his work I still find myself afraid to revisit; they truly feel like nightmares, and reach parts of me that no other films ever have in terms of evoking visceral reactions. Recently, after generously listening to me talk about David Lynch on and off for several days, I had the joy of introducing a couple good friends to the film Lost Highway (1997). Equal to the joy of revisiting what I consider to be one of Lynch’s most cohesive—but no less confounding—visions, was witnessing these friends experience a film like this for the first time. The way everyone’s breath changed during the most unsettling of scenes. The way one of them slid forward on the couch after the end credits, slack-jawed, his eyes wide, and said, “I’ve never seen anything like that. I’ve never seen anything like that.” And then how we sat and discussed the film, offering questions and interpretations to which we knew there would never be any concrete answers.

That’s another thing about David Lynch, not merely his work but his person: his willingness to live in the questions, rather than to seek for the answers. His love of those questions, and his disinterest in answers.

It has been almost two months since his death. While I’m not a frequent user of the social media platform Threads, I’ve found myself returning there more often for a simple reason: the Threads algorithm won’t stop showing me David Lynch posts. It’s become a community of people who, like me, are grieving, and who are finding solace of a kind in that sense of community. The legacy David Lynch has left behind is a truly unique one. Whereas, days before, the internet was ablaze with disappointment and shock over the Vulture article detailing Neil Gaiman’s abuse allegations, prompting the question of whether it’s possible—or ethical—to separate the art from the artist, my internet replaced this with an overwhelming love and appreciation for David Lynch. With him, there is no question of whether it’s necessary to separate the art from the artist. Lynch’s legacy among those who loved him comes down to a few themes: be entirely yourself, fly that freak flag in how you are and what you do; fall in love with the process, not with the results; create, create, create; be still, sometimes, for you are pure consciousness and there is only positivity and creativity and love to be found in stillness, in getting in touch with yourself and with those around you; don’t cling to certainty, and stop feeling the need to elaborate or explain yourself; keep hold of your capacity for wonder and dreams; find what you love, and do it.

These are some of the sentiments I continue to see echoed. These are the things I’ve always felt whenever I sit down with one of Lynch’s works, or whenever I listen to him talk about art, consciousness, or creativity. They are things I feel strongly now, and it is a curious thing: the grief mingled with the fire of inspiration.

In both everyday life and in my own artistic life, I am prone to self-doubt, anxiety, and no small amount of inner darkness. These are things I try to work on all the time, though it can be exhausting work. When I was an angst-ridden teenager, I came to believe my suffering and my writing were inextricable. Not that this was how I wanted it to be, but I’m sure many of you reading this can understand: especially in youth, before you have a clearer view of yourself, it’s easy to fall into the trap of clinging to or even romanticizing your own suffering, and therefore trapping yourself in it, seeing it as part of your identity.

For these reasons, I cannot understate the impact of somebody like David Lynch. Before him, I had never heard somebody speak so adamantly about how suffering hinders creativity rather than helps it; about how it’s not merely possible, but necessary to be content or even happy in order to better and more clearly create. And I’ve found this to be true in my own life as I’ve matured and learned to navigate the issues and darknesses of my own life. When I feel better, I not only have the drive and capacity to be more productive, I also feel safer to explore the darker regions that I most love to explore, since I gravitate strongly toward the literary horror genre. It’s from a happier place that I don’t fear writing about such depths will overwhelm me or pull me in. Funnily enough, in the months since Lynch’s passing, when I’ve had low moments or moments of hyper self-awareness that feel almost crippling, I’ve thought about David Lynch. I’ve thought about what he might tell me, how he might encourage me, and it’s been helpful. It’s been a hand up onto my feet, even if in just in small ways, but that can make—and has made—all the difference.

Being positive can be especially hard, too, when the world around us seems to be taking such increasingly dark turns. It can make each day feel like a Sisyphean task just to maintain any sense of optimism or hope for the goodness of people and the future of this place we live in. Then I think of such things as words from Twin Peaks, when David Lynch’s own character, FBI director Gordon Cole, is speaking to David Duchovny’s transgender character, Denise. He says to her:

“And when you became Denise, I told all your colleagues, those clown comics, to fix their hearts or die.”

Those words feel more relevant and more powerful than ever now. Like a rallying cry. An expression of compassion, strength, and beautiful defiance against hate. Fix your hearts or die.

There are a lot of things I’ve taken to heart in reflecting on my own grief these past months. Among them is the importance of community. Those who loved David Lynch, who’ve found each other, is testament to the kind of community that can form around kindness, acceptance, and freedom of expression—in art and in life.

I have to add, too, that it’s no small comfort knowing there was someone like David Lynch in the world, someone who grew up in the time he did, who lived to the age he did, whose view of the world expanded rather than narrowed, who lived and taught the aforementioned values of acceptance, goodness, and love. That’s the kind of person I always try and hope to be.

I often think about what it must’ve been like for the first people who went to see Eraserhead (1977) in a movie theater. It was a film unlike anything that came before it, and I’d say there’s really nothing like it today, after all this time. The experience of watching that film is one of many I can’t forget. The palpable unease; the unprecedented humor; the horror and the wonder.

When I think of Eraserhead, which may very well be my favorite film from David Lynch—if it’s even possible to pick a favorite—I think of the mind that created it. So much of the film is literally handcrafted, as Lynch built the sets and most of the set pieces, and had all the time and freedom he needed to work. From the moment he emerged onto the art scene and the film scene, he was inimitable. Entirely himself, and committed to his vision. He’s even been quoted as saying his Disney film The Straight Story, a simple movie about a man driving a tractor across states to see his sick brother, is his most experimental film. There’s something to be said about the sincerity of a mind as weird and undefinable as David Lynch’s working with a bare-bones, conventional narrative, and regarding it as experimental.

That’s my long way of saying, the great artists are those who are entirely themselves, who find their voice and give themselves to it. As someone who loves cinema and has seen a vast range of films in my lifetime, I’ve seen my fair share of the weird, the unconventional, the experimental, the obscure. But there’s just something about David Lynch. Never once have I ever felt he was being weird or obscure for the sake of doing so. What sets his work apart is his absolute sincerity, a sincerity that is palpable even in the darkest and most disorienting moments.

That heart is what draws me perpetually to him and his dark visions. Being purely sentimental about it, there have been times when I’ve felt as though his films were made exactly for me, and that his words were spoken directly to my heart. What’s amazing is I know I’m not the only one who feels that way. The art industry is filled nowadays with projects seemingly made by committee, where the main intent is to make more money by appealing to the widest possible audiences. In contrast, the authenticity of somebody as unapologetically weird and original as David Lynch is a beacon and an inexplicable comfort. And for somebody so willing to plumb the dark depths of the mind and soul, he was a shining light of a person.

I did not know David Lynch, but a few nights ago, after talking about him with a friend and re-watching another of his films—in this case, Blue Velvet (1986)—I sat down with my thoughts and came as close to meditating as I have in years. This is something his passing has had me reflecting on: how much time I actually spend with myself, in stillness, in silence.

What do you do with the grief for a person you didn’t know? I didn’t know David Lynch, but I felt seen and understood by his work, and sometimes I feel as if I did know him. I carry what I feel I’ve learned from him, and it is an empowering weight. He believed it was possible for the world to grow kinder, more positive, more loving, more creative. Because of him—and because of the people I love—I want to believe that.

And some days, despite everything, I do.

Cody LakinBy Cody Lakin, author of The Aching Plane and The Family Condition.

Lovecraft eZine: A Friendly Horror Podcast, a community, an online magazine, and more.

#codyLakin #davidLynch #dune #eraserhead #lostHighway #mulhollandDrive #twinPeaks #weirdFiction

Cycle David Lynch (1/10) : Bouches, oreilles, fêlures, terrier, crâne ouvert : « Eraserhead » est traversé par des trous, où semblent converger déjà toutes les obsessions de David Lynch. Hanté par le cerveau-effaceur du titre, Henry Spencer doit traverser ses cauchemars et ses monstres. Afin de se sauver de l’oubli, son corps va devoir apprendre à apprivoiser les trous du monde.

@jonahgibberish @wackJackle With a can of #PabstBlueRibbon and an #EraserHead

TIL (well, technically LNIL) that notable and quotable character actor Darwin Joston is in both John Carpenter's ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (1976) as wry master criminal Napoleon Wilson AND David Lynch's ERASERHEAD (1977) as put-upon button-pusher (just) Paul. Having seen both many, many times I only first made the connection late last night watching movies when by all rights I should have been unconscious. #1970s #AssaultOnPrecinct13 #DavidLynch #Eraserhead #JohnCarpenter #Movies #OldMovies #PsychotronicFilm

Happy Twin Peaks Day.

RIP David Lynch.

#ansi #ansiart #textmode #textmodeart #fanart #digitalart #demoscene #bbs #retrocomputing #retrographics #portrait #twinpeaks #eraserhead #losthighway #mulhollanddrive #davidlynch

Missing #DavidLynch right now. 💔

#movies #Eraserhead #art #gif

‘Mother’s Baby’ Review: Johanna Moder’s Latest Rivals ‘Eraserhead’ As A Visceral Evocation Of New Parenthood – Berlin Film Festival

#Festivals #Reviews #BerlinFilmFestival #ClaesBang #Eraserhead #Review

Les invitamos a nuestro programa de hoy, donde conversaremos sobre la obra y la vida del gran #DavidLynch.

21:30, hora del centro de México, en vivo:

https://youtube.com/live/zOWOynGZrss?feature=share

#cine #arte #comunidad #TwinPeaks #BlueVelvet #Eraserhead