Transcript: Episode 39: Could you fight a Meg?

Access the episode page here.

Travis Holland (00:24)

welcome to Fossils and Fiction. Thank you so much to everyone engaging with us over the last fortnight. We’re going to discuss names for our mascots later on. There have been a huge number of suggestions. We’ve also got Paleo Pulse coming up pretty shortly, which is our news topic for the week and a special guest interview. But first, I’m going to say hi to my new co-host. She’s still settling into the chair. Alyssa, hi.

Alyssa Fjeld (00:50)

Travis, how are you doing today?

Travis Holland (00:52)

Yeah, pretty well. It’s a nice hot day to be surviving this heatwave we’re having up and down the East Coast, so…

Alyssa Fjeld (00:59)

It’s 40 degrees here in Melbourne today and I’m not sure that wildlife knows what to do.

Travis Holland (01:04)

No, the animals definitely struggle. saw some good advice that if you’re hot, if you are struggling in the heat, it’s a good idea to put some water out for birds and lizards and various other wildlife around the place and try and make sure they’re looked after. And we love wildlife on this podcast, even though we mostly talk about the dead ones.

Alyssa Fjeld (01:22)

Yeah, absolutely. I’ve actually put a little container of water so you can just fill a little tupperware with water and set it outside your house. Mine is currently being visited by a noisy miner. Yeah, yeah. I know, I can’t stop it.

Travis Holland (01:33)

Noisy Miner yeah. We don’t want to support those ones, but I suppose you can’t really be picky, which birds come along to the water. Also wouldn’t wish harm on them directly as such, but yeah, exactly right. Let’s start the episode proper with what I’ve now labeled Paleo Pulse. I think I’ve just sprung that on you now, but…

Alyssa Fjeld (01:42)

Yeah, unfortunately.

Just make less of yourselves.

Travis Holland (01:57)

This is where we would discuss a recent paleo story. This one is by Barker et al out of the UK. And it looks at theropod diversity in the lower English Wealden group. Darren Naish is one of the co-authors as well. He’s quite well known around the place and particularly for research into this area.

Alyssa Fjeld (02:16)

Yeah, there’s a couple of really interesting things to me about this paper. And I just wanted to shout out to some people in my lab, Astrid O’Connor and Jake Kotevski who I talked about this article with in order to get a slightly better understanding of what’s kind of going on there. Theropods are not my wheelhouse, but they are very much Jake’s wheelhouse and Astrid is just a sweetheart. But there are two things that really stuck out to me as being interesting with this article.

And the first is that these are fossils from the Cretaceous that are coming out of a location in the UK that does have dinosaur-bearing strata, but it has something in common with our dinosaur strata here in Australia. And that is the relative incompleteness of the animals they get out of there and the inventiveness that they have to exhibit in order to actually understand what they’ve gotten.

So here in Australia, if you didn’t know, there are dinosaurs, and there are especially ones here in Victoria in the coast of Inverloch. And when we dig these dinosaurs up, they’re coming out of this deposit that really banged them up in the process of getting them deposited in the mud. So this really powerful river current was breaking these bones apart into little fragments. And that tends to be all we find here. So we have to get pretty creative in the ways that we analyze those bones.

what we’re seeing is that these are not full dinosaur skeletons either. Rather, these are teeth. They’re just teeth. So the authors of this paper have had to come up with a really inventive way of using generative AI in order to explore what the different assemblages were represented by. And the other thing that I thought was really cool about this that ties into today’s guest star is that this is material showing something very peculiar going on. And it’s something that we see in the Hell Creek formation as well.

but with a different group of animals. So in the Isle of Wight what they’re seeing is that there are an awful lot of medium sized predators as well as one spinosaurus, so a very large apex predators in this environment. But there are lots and lots of these mid, I don’t want to say mid tier, that implies I think that they’re shittier.

Travis Holland (04:14)

Well, we’re going to ask about you fighting them later, so ranking in terms of tiers might be great.

Alyssa Fjeld (04:20)

fair. So you’ve got like all of these animals that would be like I guess comparable to having like a bunch of bobcats and coyotes and all of these medium-sized predators in an environment and you start to have to ask yourself how is this environment supporting all of these different groups that have these high metabolic costs? And our guest Colin is going to talk a little bit about a similar phenomena that happens in the Hell Creek Formation.

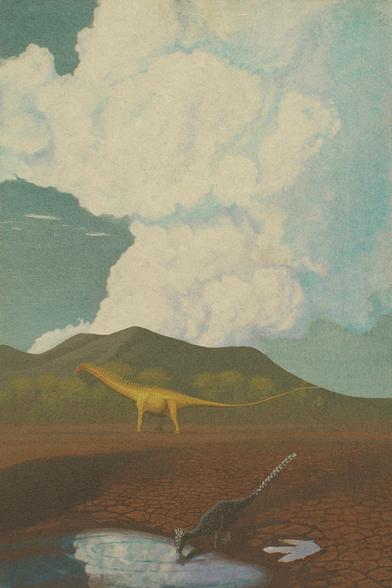

This is a U.S. deposit with super complete allosaurs and different sauropods. And what they see in the Hell Creek Formation, as Colin will talk about in a bit, is that you have an environment that is supporting a huge diversity of large-bodied sauropods. And the question you have to ask in that circumstance is, how? How are all of these delicious little grass creatures feeding, well not grass, it wouldn’t have been grass yet, leafy boys, let’s say.

How are they being supported in their environment? And Colin has a lot to say that this is due primarily to where their necks are allowing them to feed in the canopy, which I didn’t know. That’s really cool.

Travis Holland (05:23)

So niche partitioning is really important. And as you were alluding to, in this case, they’re looking at theropods, so primarily the meat eaters. And I think the thinking was previously that the sort of received wisdom was that probably there was spinosaurids and oviraptorosaurian possibilities in that location. But now you have to also consider when finding teeth or finding skeletal remains that there are

tyrannoraptoran, tyrannosaurid, dromaeosaurid as well. essentially a lot more meat eaters at this time and place than we might have understood previously. And as you say, how is the environment supporting that? If you imagine herds of tens of thousands of Triceratops, for example, as you were talking about in Hell Creek, roaming across the landscape or sauropods, how are they supported by the environment? Because you certainly couldn’t imagine that.

in the modern day landscape.

Alyssa Fjeld (06:19)

It’s just, it’s so interesting because the more we learn about these animals as animals, the more they become almost familiar to us. And then you get these monkey wrenches that throw all of that into not contention, but it it illustrates, I think that as much as we learn about the past, it really was a very different place and had very different ecosystems.

Travis Holland (06:42)

And so it points to some of those interesting questions. What were the ecosystems actually like? What were the animals, you know, their food web relationships like or the trophic relationships like? Absolutely interesting. I think it’s probably then time to get onto the guest. So you’ve already mentioned his name. I learned so much from this interview. I did the interview editing. The guest goes into so much information about details of allosaurus and I was thinking, great, this is really interesting and fun.

And then suddenly we get that switch to the sauropods you were talking about. And so he talks about scanning an apatosaurine during the research and the niche partitioning of all these sauropods as well. So introduce the guests for us a little bit and then we’ll jump into the interview.

Alyssa Fjeld (07:22)

Absolutely. Colin Boisvert is a vertebrate paleontologist who’s currently studying out of the University of Oklahoma after doing his master’s degree at the University of Utah, I believe. He is an absolutely fascinating researcher who’s looking at a mix of both allosaurs, which are the big meat-eating boys that you know and love, as well as apatosaurs. And some of that work was also co-produced by Melbourne’s own Jack Perkins, who is working at Melbourne Museum at the moment.

the really interesting things that Colin has to say about dinosaurs are rivaled only by the really cool revelations that he has about finding your way as an early career researcher. I think it, while we’re springing acronyms, I think he really has the three P’s that drive a lot of early people in paleo, right? He’s got the passion. It’s super obvious talking to him that this is a man that could talk about dinosaurs day and night. And those are exactly the kinds of people that you want in paleo because it.

often is that you might have curveballs thrown at you or you might lose funding and you really need that passion driving you to continue to reach for opportunities and do what you’re doing. And he also has that persistence that you need to do that as well. Some people say that having a PhD or getting a PhD is really more a test of stubbornness and I think that’s absolutely a case you can make. Colin really channels that beautifully into his research. I think he does a great job of explaining it himself.

And he also has the third good quality, which is pure luck. Sometimes great opportunities will come your way. And if you do what Colin does and seize those opportunities with that passion and persistence, you’ll make the most of the opportunity you’ve been given. And I think Colin just does an excellent job of demonstrating all of those qualities really well.

Travis Holland (09:03)

Fantastic Alyssa. Well, thank you so much for going out and doing that interview. We’ll jump to it now.

Alyssa Fjeld (09:12)

It’s my second episode here and we are talking with the fantastic dinosaur man, Colin Boisvert who completed his undergraduate degree, I believe, in California and then his master’s degree at BYU in Utah and is now studying allosaurs at, was it Oklahoma, Oklahoma Uni?

Colin Boisvert (09:33)

Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences is the full title.

Alyssa Fjeld (09:37)

How’s life been? How’s Oklahoma?

Colin Boisvert (09:39)

Oklahoma’s all right. It’s, it’s interesting. I think it’s finally starting to get colder. So we’ll see how the winter compares to Utah and, life’s okay. Just, you know, chugging along and clinical anatomy and, learning about the human body.

Alyssa Fjeld (09:53)

that certainly sounds exciting and probably quite interesting as a comparison to what you’re doing with Dinosaur Anatomy. Jack Perkins was telling me a little bit about your project and he said that you’re currently working with Allosaurs, is that correct?

Colin Boisvert (10:07)

Yes, yeah, so I am working with Allosaurus. I don’t know how much I can say, but I mean, I’m an open book. Basically, Allosauridae, as of this moment, if you went out into Google Scholar, into the literature, you would see a surprising situation. We’ve had different species of Allosaurus described. As of 2020, and I have a funny story involving that one, Allosaurus jimmadseni

of course, Allosaurus fragilis, had its neotype finally designated in, I believe it was December of last year, 2023. And then of course, Allosaurus europis described in 2006 from Portugal. And then of course, the ever classic, ever interesting, saurophaganax maximus is the last member of the clade Allosauridae, a clade that currently only exists during the late Jurassic period of Europe and North America. But

Like I said, as of today, if you went onto Google Scholar, and it could change in the future, hopefully, hopefully will. What’s really interesting is Allosaurus jimmadseni currently, Allosaurus europis, and then, well, specifically those two haven’t been phylogenetically placed into the family Allosauridae. We often see Allosaurus treated as a OTU, operational taxonomic unit.

where it’s just the genus Allosaurus, and then of course they compare it usually, such as in Carrano et al. 2012 to Saurophaganax and show a sister relationship between those two. But what is the exact relationship between Fragilis jimmadseni, Europus, and Saurophaganax maximus? In a small way, that’s what part of my thesis hopes to work on a little bit, but I’m just getting started.

So we’re just starting to figure it out or start to work on it. I cannot say figure it out, but start to work on it.

Alyssa Fjeld (12:00)

That sounds very-

That sounds really exciting. Now for the people out there who may not remember the Allosaurus from their Jurassic Park franchise or other children’s media, Allosaurids are a group of theropod dinosaurs that are carnivorous. And that’s kind of the extent of my knowledge about them beyond that one of them was originally discovered by one of our bone wars champions, Mr. Marsh, if I remember correctly.

Can you tell us a little bit more about what an Allosaurus is and Marsh as well, if you’d like?

Colin Boisvert (12:29)

Marsh.

Yeah, Marsh did describe, I should know this, I’m getting better. Marsh did describe originally Allosaurus, however, the story, and Cope is involved too, because Cope found bones that would end up getting synonymized with Allosaurus, but initially were described as a different taxidermy. Now, Allosaurus has a difficult taxonomic history, because funny enough, we actually have to go past both of them to Joseph Leidy

who found bones we think attributed to Allosaurus, or that we have been attributed to Allosaurus, but he thought they were from a new species of Pocleopleuron, which is a megalosaur, relative of in this case megalosaurus, the first described dinosaur. But they later were like, no, I don’t think this is Pocleopleuron, this is its own genus, so then it was redescribed as Antrodemus. And then you have Antrodemus valens.

And then later we have Allosaurus fragilis among others. But then work in the 1920s by Charles Gilmore would show, it looks like Antrodemus and Allosaurus are just the same thing. And so it gets a little complicated there. And then there’s the fact that Chure discusses Allosaurus jimmadseni in his thesis that’s out there. But then the description would come in 2020.

And then Allosaurus europaeus, first initially discussed in papers in 1999, the papers out in 2006. But really, the difficulty once again is with Allosaurus fragilis, because with Allosaurus fragilis, there’s the holotype, but the holotype is from some scrappy material that is, or scrappier material that’s in the Yale Peabody collections. And so therefore there was difficulty with, can we keep this holotype? And so that’s why there was a petition to describe in this case a neotype.

or to designated neotype. And so in this case, USNMV 4734, which is at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History or the National Museum of Natural History is now the designated neotype for Allosaurus fragilis. And then of course, there are still, I think there were claims in the 1900s made that Antrodemus was valens. And along with Antrodemus, you have

Allosaurus atrox, labrosaurus, creasaurus. These are all animals that have been later synonymized with allosaurus, and I think specifically allosaurus fragilis, but they were around. Epanterias that was the one Cope named. And then of course you have even more recently allosaurus leukocyt described in 2014, which is part of, once again, the Yale Peabody collection. we really have a question. What is allosaurus fragilis?

What is Allosaurus jimmadseni? And of course we know Allosaurus europaeus and saurophagonax, but what are they? How can we kind of constrict them and where are they all related? As to the other part of your question, Allosaurus is what we call a tetanuran which means stiff tail, as my memory serves correctly. Basically it’s a more derived clade of theropods. So we’re not including in this case, Ceratosaurus and Abellosaurs, but we are including Megalosaurs.

and then allosaurs, and then we have all of coelurosauria which is basically, if it’s not a ceratosaur it’s not an early theropod, it’s not a coelophysoid, it’s not an allosaur or a megalosaur, then it’s probably a coelurosaur right? These include Tyrannosaurs, Megaraptorans, which I do believe are separate, but once again, phylogenetics, we gotta let it take its course, ornithomimids, deinonychosaurs, birds, therizinosaurs, right? A whole swath of different theropods. But so we have allosaurs.

Allosaurus itself is distinguishable. They have some beautiful, beautiful bony crests on their lacrimal bones. They’re just gorgeous to behold and gorgeous to hold. I’ve held a couple Allosaurus lacrimals in my hand. Otherwise, Allosaurus, in this case, had three functional fingers, big claws. we think could potentially run, you know,

It’s not a lightning fast runner. We’re not talking a cheetah. This is an animal that probably more would have ambushed its prey. It could keep a pace for maybe a short distance, otherwise long tail, S-shaped neck, decently powerful jaws and based on research, potentially a very powerful neck, but as of course biomechanical models are always being updated.

Sharp teeth, right? These teeth were designed for slicing flesh versus T-Rexes, which are designed to just crush you, bone and all. Yeah, so claws, jaws, and a terrifying body. And then there are claims, we can’t necessarily state this yes or no, maybe Allosaurus was gregarious, whether that’s probably in this case more an opportunistic gang sort of situation versus a traditional mammalian pack or family unit.

but word’s still out.

Alyssa Fjeld (17:21)

I saw some literature indicating as well that they can unhinge their jaws quite wide. Do you support that hypothesis?

Colin Boisvert (17:29)

I don’t think I’ve looked into enough of the biomechanical models regarding that research in order to give a solid yay or nay. Now from what I’ve heard, Allosaurus does have an extra joint in its lower jaw. And so I believe from what I’ve learned that that lower joint would help with expanding the mouth. So I think it is possible. I don’t know if it could fully unhinge.

but it could definitely go for, I think, a wide gape and potentially start to expand the jaw

Alyssa Fjeld (17:59)

very useful if I wanted to consume a whole ornithopod or other delicious creature from the time. So you said there were a couple of new things in the world of allosaur research and you talked about a 2020 paper that you have a fun story about. Can you tell us what’s new and maybe your funny story?

Colin Boisvert (18:17)

Yeah, of course. So 2020. 2020, we didn’t know it, I didn’t know it, along with a big year in general with a lot of interesting events. 2020 would also be the year that I’m walking into my microbiology class at University of California Davis. You know, it’s a Friday morning, I’m tired. I got class all day. And I’m like, all right, let’s just get through this. Or actually, it wasn’t microbiology, was cell biology.

It’s like, right, let’s get through this cell biology class, because I struggled with cell biology. I had to really, really work at it, and it was a difficult class for me. And of course, you you try to keep your ears to the ground, and you got Discord, and you got Facebook, your other social media popping up with news articles about a new carnivore discovered that, you know, blah, blah, blah. yeah, I think it was the classic, right? New carnivore discovered relating to T. rex. According to popular media sometimes,

every new theropod is a relative of T. rex, isn’t entirely inaccurate. It’s just, you know, it’s like, well, there are some things that are actually closer to T. rex that are other tyrannosaurs. And then there’s, hey, this is an allosaur. How about you say new theropod related to allosaurs or, you know, let’s bring in Jurassic world, new theropod related to giganotosaurus, right? So, but it’s always, cause you see these articles all the time, they discover and describe a new abelisaur, something that is very distantly related to T. rex. And they’re like,

new theropod from Africa related to T. rex discovery. And there’s been a few times where I’ve seen that and gone like, wait, did they find a Tyrannosaur in Africa finally? And then it’s like, no, it’s an abelisaur. I need to stop falling for this. So I had my doubts when I see this article and there was a piece of paleo art with it, but I clicked the article and I think I remember swearing because I was like, holy.

Because I read it and it’s saying, yeah, University of Utah just announced or they’re about to announce today prior to their Dino Fest, an annual event they have at the Natural History Museum of Utah and Salt Lake City. They’re about to drop, they described a new species of Allosaurus and I clicked the link and follow it to Peer J and start trying to look through the article, but I was just ecstatic the rest of the morning. I forget what my lecture was about. I just kept thinking, yo, we got a new species of Allosaurus from North America. This is amazing.

And especially in this case, a very famous specimen, MOR693, otherwise known to the public at times as Big Al, which was the star of a documentary, Allosaurus, a Walking with Dinosaurs special, or the Ballad of Big Al, is actually a member of this new species. It’s considered a referred specimen to Allosaurus jimmadseni. So that was just really cool to think that it’s like, whoa, there’s a new Allosaurus on the scene and it’s already got a, I mean, it has a holotype from Dinosaur National Monument and it also had, I’d say, a spokes.

spokesmember with Big Al. So that was really cool. Even more recently, we had Meraxes gigas, a carcharodontosaur. It’s always exciting when we get a new carcharodontosaur And especially with Meraxes, it’s very interesting because of the whole forelimb. They see forelimb shortening happening similar to tyrannosaurs. And so it’s a question of why is this happening? And it seems now maybe this is a general trend.

across multiple bodies of large-bodied theropod dinosaurs, this is occurring, especially because just very recently, we have new referred material to Taurovenator which was considered earlier on, a dubious carcharodontosaur genera, especially because was based on the holotype was a post-orbital, but now we have extra material. It does look like it’s different, and it also shows this four-limb shortening. So it’s like, okay, seems to be a common trend.

This is very curious, you know, what’s going on here. And along with that, we also have a Metriacanthosaur that was just described earlier this year in, I believe it was in August. it’s from Kyrgyzstan and that’s really exciting because based on when it’s found and where it’s found, would…

be amazing in my book if we could get a biogeographical study on this animal because there seems to be this trend, and maybe it’s just me, there seems to be this trend popping up where we’re seeing that with regard to the allosauroids story, you have Asfaltovenator from South America, which is kind of the, wait, how did that get there? I’m confused. But otherwise, the rest of the earliest allosauroids and the earliest Metriacanthosaurs are all in Asia.

It kind of seems like they’re spinning a loop in Asia and they just keep pumping out new genera and that’s where they start. And then we see eventually a strand, I’m gonna call it, I don’t know, that’s technically not true, a branch. A branch eventually leaves and gets to, we have Metriacanthosaurus in Europe around 160 million years ago. And now between that species 160 million years ago, a few other Metriacanthosaur such as in this case, Sinraptor, Yangshuanosaurus, which are around the same age.

and a few maybe older ones and older Allosauroids We now have right, I would say, about the same time and also in the middle, you have our new genera from Kyrgyzstan. So it kind of seems like we can say, all right, there was definitely a migration from Asia to Europe. And then of course, once we get to Europe with allosauridae that’s a nexus point. The late Jurassic was a very interesting time, it seems, for allosauroids because we have, in this case currently, the last of the Metriacanthosaurs.

We also get potentially one of the earliest, if not the earliest, Carcharodontosaurus with Lusovanator in Portugal, as well as we have our Portugal Allosaurus species, Allosaurus europaeus. And then obviously from there, will also then later have, or later or potentially at the same time, have Allosaurus in North America. So were they diversifying in Europe and then spreading out or is it maybe the opposite

Alyssa Fjeld (24:02)

Very, very interesting, especially thinking about, I suppose, what we get here in Australia where there’s very little, I assume, and Jake Kotevski can come for me if I’m wrong about this, but my understanding is that the theropods we get here exhibit very little forelimb shortening, so their arms are not retreating as we think about the typical T. rex arms.

And it’s interesting as well that these animals are doing this diversification in the Jurassic. I think it’s pretty common knowledge now that most of the dinosaurs that we feature in Jurassic Park are not actually from the Jurassic. So you could, in theory, then, have your Allosaur as your major predator, and that would be pretty exciting.

Colin Boisvert (24:42)

Yes, and equally terrifying in terms of the media. Before T. rex took a major step on the scene, a lot of times, I think even in literary work, Allosaurus was used once it was discovered as the big terrifying dinosaurian predator. It was top of the heap. It has a major starring role in The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

with one of my favorite adaptations being the 2001 A &E movie. so yeah, so Allosaurus is a terrifying predator. It also got a spotlight, which was amazing in Battle at Big Rock with the Jurassic Series.

Alyssa Fjeld (25:23)

just to backtrack a little bit, you mentioned that this was something, these new discoveries were starting to come out even when you were in your undergraduate degree at UC Davis. And I think that’s a pretty typical story for a lot of us in paleo. This is something that is an interest that has followed us for a significant portion of our lives. It sounds like that’s something that would be true for you, a long life long interest in dinosaurs, specifically allosaurs or has it changed?

Colin Boisvert (25:49)

no, it hasn’t really changed. I think it became defined. So I’ve loved dinosaurs since I was a little kid and I grew up in one of the most, I want to say interesting places to love paleontology, which is I grew up in Silicon Valley, AKA the tech capital of the world. So, you everyone’s looking to the future and Colin’s looking to the past. the, the kind of biggest and most

Natural history-esque like museum that I grew up with was the California Academy of Sciences, which is an amazing museum, but they even pride themselves on when it comes to natural history, they’re not a standard natural history museum like we see in the movies and we visit in places such as Utah and New York and such. They focused more on the natural and then the history is kind of part of the background in terms of them describing processes such as evolution and how that works and adaptive radiation.

Sure, you’re greeted in the front of the Cal Academy, the new building as of 2008 by a T. rex. But besides that T. rex and a few other mentions of fossils, it’s a lot more learning about, you know, biodiversity in the oceans, right? They have a huge exhibit on coastal environments, especially because California is a coastal state and, you know, our coral, not coral reefs, sorry, kelp forests are very important. They have a rainforest dome. They have a hall on Africa, which does have a little bit on hominid evolution.

So I grew up Silicon Valley, right, in a very different place, but I’ve loved dinosaurs since I was a kid. I was always trying to talk to everyone I knew about dinosaurs. It oftentimes became a lecture. So it was very difficult. It was in high school as I was starting to figure out, you know, where did I want to apply to college? My dad and I did a trip to the University of Wyoming and it was there that I really got my first glimpse talking to them regarding, you know, how undergraduate and future work with.

paleontology works that I learned, you they said, well, you know, when people tend to specialize, right, you can say, I want to study dinosaurs, but then people usually study specific type of dinosaur or use a specific group of dinosaurs as a case study with specific methods. So that’s where I really started to think, well, what did I want to study? Since I was a little kid, I had loved, and it still is my favorite dinosaur, Giganotosaurus, and that is probably mainly because of Nigel Marvin.

and his Chased by Dinosaurs special, which I watched so many times as a kid. And technically it features Mapusaurus that we now know, but at the time they thought it was Giganotosaurus and it’s a beautiful special, it’s 30 minutes, amazing. I’ve actually talked over COVID, funny enough, Nigel Marvin, he basically put on his website, you can still do it. You could basically pay him to have a Zoom call with him. So I was like, yes, please.

So I talked with that man and told him what I was studying and said, I loved everything you worked on in the early 2000s. You know, I’m a huge fan. was a great conversation. He’s, he’s an amazing person. Super nice. But, so I realized I wanted to study allosauroids. And so I came to college and, college was really, it was a great experience, obviously, even in the end where things got crazy cause of COVID, but college was eyeopening where I learned, right. And I can’t believe I didn’t see this coming.

Shocker. Not the biggest fish in the pond when it comes to what you know about paleontology. mean, obviously I had professors and I knew I did not know more than my professors, but even among just the other undergraduates and of course the graduate students, right? I don’t want to say I learned my place, but I kind of learned to, in my case, stop talking and just listen and see what I can learn from others. And I learned a lot.

I I became quieter and I didn’t necessarily voice my theories all the time. I tried to, I think, become more calculating in terms of, you know, I think we can make this claim based on this evidence. And I think that’s especially reflected towards the end of my time at UC Davis. Yes, I rushed it a little bit more and I should have taken a longer period of time, but one of my favorite things was in an ecology class I was taking, I ended up writing on one of my favorite subjects.

from one of my favorite paleontologists, Scott Sampson, right? He wrote an amazing article in the Scientific American that came out in 2014 that basically just asked the question and discussed a situation regarding, all right, Laramidia, roughly, as I remember, half the size of Australia at anywhere from four to seven million square, I think miles in this case, but similar in size to Australia.

and a fifth of the size of Africa. Africa today features, I think they said, about a half dozen mega herbivores, herbivores over one ton in weight. Laramidia, you know, anywhere from 80 to we’ll say 70 million years ago, and just for ballpark 75, has over two dozen. What is happening? Why is there an over saturation of so many mega herbivorous dinosaurs in Campanian Laramidia, right?

This shouldn’t be possible. This shouldn’t be able to fit the environment. And so that ecology class allowed me to really dive deep. And I kind of did a lit review term paper where I basically said, okay, here’s the question. Can we use the current literature to try to explain this? It turns out we might be able to. And with regard to the histology of the prey versus the histology of the predators, AKA our predators, especially tyrannosaurs, were getting to adult size if they made it.

At about the same time that our herbivores were getting into their older age, combined with surprising sources of food from potential bark to crustaceans that maybe our animals weren’t necessarily just always eating the softest plants, they would go after other sources of food to supplement their diet. And there seems to be kind of a, as we often expect in nature, a multi-factor mechanism for how we can explain why so many large bodied mega herbivores

Herbivorous dinosaurs are surviving in Campanian Laramidia Now obviously time is a factor. They weren’t all living at exactly the same place and time, but we have multiple quarries where we know, all right, we have at least one ceratopsian and at least one chasmosaur, potentially one lambiasaurine and one saurolophine as well as an ankylosaur and a pachycephalosaur and potentially a few others. So we know there are environments where we have a lot of these animals. And then we have multiple of these.

that are at roughly the same age? So it was a great question. So that was, I think, really important for me. My professor said, yeah, your paper’s kind of a little, you know, arm wavy in terms of, I think, drawing attention, but hey, sometimes we need those studies to get people’s attention and say, hey, I know we’re all slowly coming here, and there have been a ton of people doing amazing work with this that are showing that there’s definite niche partitioning happening. And then we have, of course, you know, the alternate diets.

and then we could probably bring histology into it and other factors as well, such as maybe what we’re seeing is these animals could have had lower population demographics. So there are so many of these animals, but maybe they didn’t have massive herds. Now they definitely had to have some mass, because we know we have a centrosaurus bone bed with over 10,000 individuals in Canada, but maybe they all weren’t like that. Maybe some were rarer than others in terms of population dynamics. So that was an important thing that I think helped me.

learn a bit more about the scientific method and learn to structure my ideas.

Alyssa Fjeld (33:15)

have several thoughts about this. First, crabs, how exciting, my gosh. That is like, detrophagy in, so the eating of crustaceans and other hard-shelled mollusks in dinosaurs would be thrilling for me as an arthropod person. We love to see a crushing plate. I’m not saying that they had crushing plates, was, now I’m just imagining a sauropod with like a Port Jackson style mouth going and I want that to be real, so.

Colin Boisvert (33:17)

Hahaha

I think it was crabs, otherwise it might’ve been gastropods. All I know is it was invertebrates and it was surprising that when I read it, I was like, I did not expect that, especially from these herbivores.

Alyssa Fjeld (33:52)

Next thing you know, we’ll be finding evidence for the garlic butter recipes in the Cretaceous and Jurassic as well. My next thought is, I think it’s really interesting that you also grew up in an area that did not really have a lot of natural history in terms of the museums and other readily available public institutions. Tennessee does have some absolutely fantastic museums and we also have north of Maine.

Colin Boisvert (34:15)

ETSU.

Alyssa Fjeld (34:17)

Yes, ETSU has a fantastic, I believe it’s Cenozoic Animal Deposit known as the Gray Fossil Site where you can find just a fantastic array of very well preserved mammals and other sorts of things. the closest museum to me was a children’s museum that had like a PVC pipe you could pump air through to simulate the sound of a parasaurolophus office honking.

And I think there’s that element of mystery that exists within the context you grow up in that can be very motivating. And I think as well, you have the other three key ingredients that I see time and time again with other paleos. You had the creativity, drive to yap about it. I think the yapping tends to be, we’re all into the yapping. And then you got the tempering. So the ability to figure out where and when your creativity and your

capacity to convey that science becomes the most important and when it’s time to listen to others to help you resharpen those arguments. So I think that’s really interesting. I wanted to ask a little bit about your journey after you graduated from UC Davis. So I know you did a master’s degree. Would you like to talk a little bit about that?

Colin Boisvert (35:28)

Temperance I’ve had to learn firsthand. An important story I didn’t mention was when I was a middle schooler, some family and I actually went up north into Oregon and basically checked out John Day fossil beds. And along with that visited fossil Oregon where behind their high school you can dig for plant fossils. And that was really kind of a first experience for me with digging and where I learned a lesson the hard way because I

took my rock hammer and just whacked in the hillside, both thinking, I’m gonna find the dinosaur. They say you can’t find dinosaurs here. I’ll dig deep enough to find it, as well as, I probably broke a few, I did, broke a few plant fossils along the way. And I actually found, I think a lot of the plant fossils I ended up taking with me in the refuse pile from other people. But I learned through that, I’m then visiting a specimen where they showed how a hyper-enthused,

What’s the right word here? Hyper-enthused person who ended up finding and then I think donating a specimen, as I remember from the exhibit, to John Day fossil beds in the process kind of damaged the specimen and how patience was really important in this field. The other thing, funny enough, it’s slightly gotten better. We also have a children’s discovery museum in San Jose and it actually now houses, I forget what year it was, I was in high school though.

They found along the river that runs through our town the bones of a Colombian mammoth that died in the area and now its fossils are in that museum.

Colin Boisvert (36:54)

I was applying to grad school and I decided to apply to more programs and I’m glad I did. And I applied to a mixture of PhD and master’s programs. and, and along with that, I was applying to internships and what ended up happening is out of, applied to nine programs. I got into BYU, and I also got into an internship at the Mammoth site in Hot Springs, South Dakota.

Before I then came home, quickly packed up my stuff and moved out to Provo, Utah for my masters. So the internship was amazing. We went to so many cool places, checked out a lot of cool things. I was an education intern, so it literally was my job to yap to people about, here’s why paleontology is important, here’s what we’re discovering at this site. It was a sinkhole.

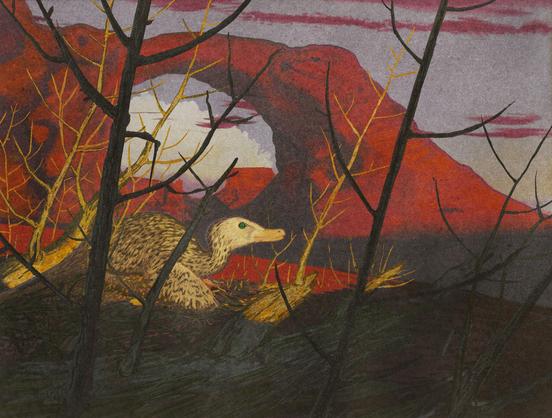

I even wrote a parody song about it, it’s beautiful. And then I started my masters and my masters, I had a chance, I could have described a specimen of Allosaurus that they had, or yeah, a specimen there. But instead I ended up working on, there’s a specimen, BYU 18531. It is an Apatosaurine.

that is from the Brushy Basin member of the Morris Formation which is a Lake Jurassic rock unit here in North America. This specimen was found down south near Moab, Utah. So right near Arches and Canyonlands National Park. This specimen was originally discovered by a local rock shop owner named Lynn Ottinger and his son, Sonny. And then they reported it to BYU, who got permission from BLM because it was on BLM land.

And then BYU excavated the specimen between 2007 to 2009. And that’s a funny thing because people would always ask me sometimes when I gave presentations on this specimen, did you get to help dig it up? And I was like, no, I was in fifth grade. So I did not help dig it up. That would have been very interesting though as a fifth grader doing that. But this specimen was unique. And I’m actually going to be speaking about this on Wednesday for the Moab chapter of the Utah Friends of Paleontology on my thesis.

The specimen is relatively complete with an almost complete neck. apatosaurines generally have, they have 15 neck bones, 15 cervical vertebrae. They found C2 through C15. We were only missing the atlas or C1. These bones were relatively complete with minimal distortion. So it provided a chance to ask the question, how did this animal hold its neck? So basically I did a study looking into

the what we call OMP, Osteological Neutral Pose, So how did, how might this animal potentially held its neck? That’s what it was. It was focused on obviously the neck biomechanics. We wanted to potentially try to get range of motion in there as well, but that did not happen in the timeframe. So in the future, that’ll have to be done.

So it was still really interesting. This project involved, we had to do photogrammetry for cervical two through cervical 13. We ended up using, at the end of my first year, they purchased a Faro scanner, which is a 3D surface scanner. And that’s how we would get models of dorsal two through dorsal four, because this animal has almost all 10 of its dorsals. Now you’re asking, Collin, you forgot C14 and C15 and dorsal one. What are you doing? I didn’t forget.

those bones were still attached by a matrix. They were left together. Whereas every other bone, because once again, this was an articulated neck, was separated from each other. We took those three bones to an industrial CT scanner down in Southern California, NSI North Star Imaging, where we put these bones into an industrial CT scanner in order to get CT scans of them and then use CT segmentation in order to figure out

What do these bones look like? And, you know, in this case, how far apart are they from each other in terms of intertubal spacing? For reference, this industrial CT scanner, the average hospital CT scanner uses about 0.1 million electron volts. We bombarded this specimen with 6 million electron volts and the scan took 30 hours.

Alyssa Fjeld (40:51)

gosh.

Colin Boisvert (40:51)

Yeah, but so that’s how we got models and then I did CT segmentation or as I like to call it the world’s worst form of adult coloring into yeah, took almost six weeks and then we had these models. Now for a lot of these models, not all of them due to time constraints, we realized, wow, they’re not really distorted but there is still some distortion due to diagenetic alteration as well as human preparation.

For cervical 3-3, cervical 13, we try to digitally restore the bones as much as possible around problematic areas, especially focused on the, in this case, condyle or the cup at the front, the cotyle, the cup on the back, the ball on the front, and then the pre and post-sci hypotheses basically faces where these bones are articulating with each other. So we tried to take these digitally restored models in order to put them through an animation program known as Autodesk Maya, as well as we used scale.

3D prints from our engineering lab on campus to physically rig a dinosaur neck and therefore compare virtually and physically how did this animal potentially hold its neck? And what we found is, right, well, this animal was actually kind of holding its neck, not necessarily straight, not in the classic S shape. What we found is it had a transition point at dorsal one and then it basically

was a sinusoidal drooping neck, so it went up and then down. So, but generally it was down for at least this specific animal. Now, I’d like to preface from what I’ve seen in the literature and what I, I think I have come to the same conclusion based on the literature and seeing other dinosaur necks, especially other sauropod necks. I don’t think it’s necessarily a one fits all model when it comes to sauropod necks. This mamenchisaurus on my shirt probably has a different neck posture.

than the, I think it’s Argentinosaurus or Diplodocus on the back of my shirt. Different clades probably had different neck postures and potentially even different intraclade neck postures. Who’s to say that Diplodocus had the same neck posture as Apatosaurus? I mean, my thesis gets into a core issue, another large issue of what I like to call CMSI, the Coeval Morrison sauropod issue. It’s not a murder crime scene that we are.

technically studying dead bones. But how do so many large-bodied long-necked animals multiple times larger than an elephant live in the same place at the same time? This is nowhere more prevalent than at Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry, which is a BYU locality where there is evidence of at least six different sauropod genera at this one single quarry.

It has Apatosaurus, Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Supersaurus, Diplodocus, and Haplocanthosaurus, and then potentially Barosaurus So at least six genera of sauropods in one locality. Okay, if we have six animals that are, in this case, even multiple times larger than our mega herbivorous Campanian dinosaurs, our ornithischians,

And there are still ornithischians in the environment. There’s gotta be some kind of extreme niche partitioning or other multiple variables for how these animals are able to live at the same place at the same time. And neck posture is part of that because neck posture gets into, well, based on how this animal is holding its neck and how far it can move its neck, that can tell us a little bit about the feeding envelope, which is work that has been done by scientists such as Ken Stevens. And then, you know, from feeding envelope, you can get an idea of, this one has this feeding envelope and this one has this feeding envelope. And so you can try to figure out, all right.

How are all these different sauropods feeding? Of course, getting back to it, that kind of requires that you have a lot of nice necks and we don’t always have a lot of nice neck fossils for sauropods. So we have to use what we can to figure out what’s possible.

Alyssa Fjeld (44:37)

fascinating. I can’t imagine an environment with that many large herbivores in it. So you’re saying that it’s essentially that the necks are allowing them to vegetation at different heights within the canopy. Would that be correct?

Colin Boisvert (44:48)

Yes, I would say so. These animals are likely feeding at different heights and even there’s evidence, right, that Apatosaurus, even if Apatosaurus, let’s say, wasn’t feeding high in the trees, there’s evidence biomechanical models to indicate it might have been able to rear up. And so if it is able to rear up, in this case, kind of like a kangaroo, maybe balancing on its tail a little bit, this animal then might have been able to reach high into the trees occasionally.

to get its tall greens, but for the most part, maybe it wasn’t always doing that, especially if its neck posture is further down. there’ve already been some claims made that like Camarasaurus was maybe kind of feeding in the middle, mid-browsing height, brachiosaurus was a high browser, and then claims that animals such as diplodocus and apatosaurus might’ve been feeding lower, so.

Alyssa Fjeld (45:19)

you go you go

it makes sense that you would have different neck posturing in this really diverse group. Like I think this is something that a lot of people don’t necessarily, I think it’s something that if you said it to them they would go, yes that makes sense, but sauropods, theropods, the diversity of dinosaurs even within these familiar groups is tremendous. The number of different species we get and the different life habits, it’s very fascinating.

Colin Boisvert (45:57)

In terms of the whole actually, you different sauropods had different neck postures. Well, you definitely get that if you read a lot of sauropod neck poses, but what I was finding with my thesis, especially at the end is,

In terms of, we had a hypothesis, we rejected that hypothesis, and we found a neck that was like this. So in terms of what was this animal likely eating on? Well, I had to really go into the literature and expand because you have to start using other pieces of evidence that are also independently pointing or providing evidence for a similar conclusion, right? So there’s evidence that a close relative of Patosaurus, Nigerosaurus, has a really high tooth replacement rate. So dinosaurs, unlike mammals, are constantly replacing their teeth throughout their lifetime.

And we’re seeing in some diplotocoids, such as Nigerosaurus, that they’re really replacing their teeth very rapidly. Like we’re talking, a tooth gets replaced, I think it was between every 15 to 30 days a tooth is replaced. And so one of the ideas is, well, why are they replacing their teeth so fast? Maybe it’s because they’re eating abrasive vegetation. What usually in this case is abrasive, a lot of ground growing vegetation. Now you have to remember though, in the late Jurassic, we don’t, as far as we know, have grasses.

which are the general abrasive vegetation we might think of today, especially with horses. So in this case, these animals are feeding on other ground-growing vegetation that’s wearing down their teeth super quick. that using phylogenetics, this apatasaurine, BYU-18531, also might’ve had quick replacement rate on its teeth. That coupled with a apatasaurus’ muzzle, or kind of its snout, is a little bit broader compared to some of its relatives. And Nigerasaurus has a very broad snout, and in mammals, a broadening of the muzzle

has been correlated with kind of being a grazer, combine that with, you know, cranial biomechanics, which indicate diplodocoids, likely were able to rake food in because they had non-occluding dentition, and so that allowed more translational movement, but they had weaker bite forces compared to other animals, and that weaker bite force may have helped with eating, in this case, vegetation that’s lower to the ground and likely softer versus hard woody material.

you kind of start to paint a picture that, all right, maybe all these things are adding up that this animal was feeding on one specific area of its environment. And then the same thing for other sauropods. I people, I think with Camarasaurus and brachiosaurus keep coming back to that conclusion that those types of dinosaurs seem to be feeding more in the mid to high browsing range. And I don’t think anyone has really made a claim yet that Camarasaurus.

the most common sauropod in the Morrison, so we have a lot of them, was grazing on the ground.

Alyssa Fjeld (48:33)

fascinating. That is so much good information about sauropods and I can’t wait to hear what you end up publishing from it. I’m sure we are all looking forward to that. I just wanted to ask a couple more questions quickly before we wrap up. So the first question I have for you is Jack Perkins at Melbourne Museum who was telling me, and I know guys I say the R in Melbourne, it sounds worse if I don’t.

Jack Perkins mentioned that you guys are working on something and that you didn’t mind giving us a little sneak peek. Is this also to do with dinosaurs?

Colin Boisvert (49:03)

This does also have to do with dinosaurs, yeah. So what Jack is referring to is last year at SVP, I gave a presentation on a project that actually started with some coding classes I took at BYU. So, hypercarnivorous megatherapods, theropods over a thousand kilograms in weight. We have in this case roughly five clades that contain members who would be considered hypercarnivorous megatherapods.

These are some of the most charismatic theropods out there. People know them. People sometimes love them. Other times they don’t love them. They include, in this case, tyrannosaurids, which includes our famous T. rex, right? One of the most classic examples. It also includes megaraptorans, or at least megaraptorans, and I, we treated for this project megaraptorans as coelurosaurs but separate from tyrannosaurids.

And we have a few Megaraptorans that are definitely over thousand kilograms. And they are kind of a large, medium to large body predator in the environments they live in. Then we also have now Ceratosaurians, right? Ceratosaurians such as especially Abelosaurs, right?

Then you have megalosauroids, which includes spinosaurus as well as megalosaurus. And finally, last but never least, allosauroids which includes our allosaurus, our metriacanthosaurus, our carcharodontosaurs our neovenators such as neovenator. So we have these five clades and I initially just asked the question, okay,

Where in time and space do we see these clades coexisting with each other? Can we start to a story of who’s coexisting with who, when, and what’s going on? And as we started to plot these things out, where we gave each of the species initially a temporal value and a spatial value, so a single landmass, we started to see some interesting trends in terms of where things were popping up, who was popping up with who, and what places were they popping up.

And so a lot of the earlier work when it was focused on this temporal spatial overlap found there seemed to be a trend of earlier temporal spatial overlap in the kind of Northern Hemisphere and Europe, which we treated as a Mesozoic ecotone or place where you have faunal mixing from multiple communities, especially because Europe, we see classic fauna from the North and we see fauna from the South, especially in the Lake Cretaceous where you get titanosaurs and abelosaurs mixing with hadrosaurs and

potential new ceratopsians. Europe seems to be this faunal mixing pot. So that’s why we said, well, we’re going to treat Europe as different from the rest of the Northern hemisphere, or in this case, Asia and America. And then this trend was followed by latter Southern temporal spatial overlap. As we started digging into the literature more, we started to see some trends regarding potential, the size classes as defined by Holtz’s 2021 paper between these animals.

coupled with, along with that, know, all right, who was overlapping with who and who doesn’t overlap with who, we have yet to find, as far as I know, a confirmed abelisaur or a valid abelisaur genus with a confirmed valid tyrannosaur genus. So abelisaur and tyrannosaurs don’t seem to be mixing. Megaraptorans and tyrannosaurs also, I believe, they live at certain times near each other, but we haven’t found them, to my knowledge, confirmed in the same environment yet.

So we had some interesting questions and we were able to use some of the literature to try to help explain some of the trends we saw on the data. Now the project has morphed a little bit, so we’re more looking at kind of the relationships regarding those size classes and less temporal spatial overlap. But we’re still trying to get a story kind of regarding the, right, in terms of who lives with who, what is going on as these five different clades evolve and diversify?

Because there’s a lot of evidence, one specific example is there seems to be this evidence that with regard to potential temporal spatial overlap, near the end of the Cretaceous, we see abelisaurus and we see megaraptorans both in South America. However, what the literature discusses seems to start to happen is there kind of starts to see, there starts to be this split where you have abelisaurus in the North in Brazil.

Alyssa Fjeld (52:42)

That is fascinating.

Colin Boisvert (53:07)

and then in Patagonia into the south you have megaraptorans but you don’t have them in each other’s environment. So it seems they almost kind of split the continent a little bit in half and say, okay, you stay on your side and I stay on mine. That way they’re the, least the hypercarnivorous predatory ones aren’t competing with each other. But of course, you know, the word is still out on if that is exactly happening. It’s just there have been several papers discussing, well, maybe there seems to be this kind of.

difference in the fauna between north and south South America.

Alyssa Fjeld (53:36)

You know, they’ve split the continent evenly between those who skipped leg day and those who’ve skipped arm day, which is of course the best way to divide yourself up. I have one more question for you before we wrap up.

Colin Boisvert (53:40)

Ha

Alyssa Fjeld (53:46)

You can choose your own adventure here. either I would like to hear you tell me about the worst example of either a sauropod or an allosaur that you’ve seen in popular media so you can have a little rant if you’d like. Or if you’d like to tell us about some media you recommend, if there’s a particularly good example of how these animals are discussed and displayed.

Colin Boisvert (54:07)

I’ll go with the positive versus, you know, in this case, just disparaging one type of media. I think in terms of what really works, it’s still revolutionary for the times. A lot of the early 2000s work with the Walking with series is fantastic for any type of prehistoric animal, because from some of the classic lines that stick with you to

Alyssa Fjeld (54:12)

Yeah. There.

Colin Boisvert (54:32)

to the CGI, the stories that were told, we got realistic animals, animals that fought, that died, that tried to breathe, that tried to survive, right? The predator did not always win. We can see that with Big Al, who literally, MOR693 in that series kept getting injuries from different points throughout its life. I believe the total now is up to 20 pathologies on one single skeleton of an allosaur.

So it’s really interesting and they treated it that way, right? As they put, it’s called, Big Al represents a frozen moment in the fast and furious life of a carnivorous dinosaur, as I remember the line correctly. And so these documentaries were fantastic. One that has especially stuck with me, and it’s difficult because you mentioned you’re from Tennessee and this documentary relates to both of us, but it also

doesn’t really touch on either of our state’s Mesozoic history is when dinosaurs roamed America. This was narrated by John Goodman, who people might recognize as the voice of Sully from Monsters, Inc. And so to just hear Sully very sometimes grimly and just kind of very intense give lines such as, there’s one more surprise in store, mom. Or for the male, there’s always tomorrow.

It was a fantastic documentary that also told some amazing stories, treated these animals, once again, almost as if we went out and filmed them on the plains of Africa or the Great Plains of North America today. It didn’t try to tell gruesome, terrifying stories. You had underdogs, had evolutionary underdogs who would grow up. We had other animals who hit their prime and then had their time and were done.

And so these were some really great documentaries. Otherwise, mean, I also, it’s specific to the Maastrichtian but Prehistoric Planet does a really good job with a lot of the science it discusses and the animals, how they act and behave, and some of the science that went into the program and some of the scientists who get to discuss, you know, what went into the program there.

Alyssa Fjeld (56:44)

I think that’s a really, like you’ve made a really good point as well because we often, I think that when we look to media like Jurassic Park to portray dinosaurs, right, they are fiction stories that are trying to convey other things. It’s not necessarily about treating these animals as animals. They’re allegorical, they are mysterious, they’re meant to be, you know.

bad guys to some extent. So it’s interesting when we do get docu-series that treat them as living animals and it’s I think important as paleontologists to keep that aspect in mind and treat them as things that would have lived and done all of these things, eating, procreating, much like animals today.

So that, I would agree. think that those are all fantastic pieces of media and I feel very relieved to hear that the Allosaurs in those were depicted well, so I can now continue to rely on those as my source of information beyond yourself. I do want to thank you for a interview and so much amazing information about sauropods, Allosaurs, and everything in between.

Where can our listeners find you on social media?

Colin Boisvert (57:53)

On Twitter, I think it’s @ColinBoisvert1 and I believe on Instagram it’s @ColinBoisvert54 You type my name, you should see my face, it definitely looks like me. In fact, I think my Insta page, if I remember correctly, is me, funny enough, holding a cast of an Allosaurus Jimmadseni skull. So people will say, yeah, it’s that guy.

Alyssa Fjeld (58:15)

It definitely is.

so do give Colin a look, give him a follow, and keep up with his work. It sounds like there’s plenty of exciting stuff in the pipeline for our listeners to turn to.

Travis Holland (58:29)

so that was such a great chat with Colin He really talked a lot about that thing we discussed of how many big herbivores you can have living in one location Which is also one of the puzzles in that English theropod discovery I learned so much from that chat. I think

You know, he could talk all day or for weeks without a break by the sounds of things and I could listen.

Alyssa Fjeld (58:50)

Yeah, absolutely. And he was so patient with my needing to record while I was in the US on my museum trip and bopping around New York. He really tolerated the background noise, which I hope our listeners will as well. Yeah, it was just a fascinating chat. And I’m so glad that he came on the show. I hope you guys will continue to follow him on his adventures in paleo.

Travis Holland (59:10)

Let’s have a chat now about naming our fantastic mascots for the podcast. These were designed just to remind people these were designed by Zev Landes who is a fantastic artist, paleo artist. And also he just creates all sorts of other art. We’ll put Zev’s details in the show notes so can go and check him out. And we had so many good responses to this. I was like…

I was nervous as to with anyone would even respond, but so many people did. We put this up as stories on our individual stories on Instagram and on the Fossils and Fiction Instagram account and also on Blue Sky and the responses just poured in from all over the place. So, paleoastroid on Instagram, which is Astrid O’Connor who you’ve mentioned already today, former guest on the show gave us a whole bunch of suggestions.

Astrid suggested Chomper for the Australovenator and Dave for Estaingia the trilobite. And also, direct to Alyssa Astrid gave you another suggestion,

Alyssa Fjeld (1:00:14)

And it was Tang and Tor. So it’s Estaingia taking the Tang from there, and Tor from the end of Australovenator

Travis Holland (1:00:22)

like that one. Jimmy Waldron, another past guest on the show from Dinosaurs Will Always Be Awesome, also an excellent dinosaur podcast and educator out there. Suggests Scratch for the Australovenator and Skitters for the trilobite.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:00:36)

Thank you. And then we also had a suggestion from, and I’m so sorry if I’m saying your name wrong, we’ve been mutuals forever on different social media. Sauriazoicillus suggested Scuttle and Claw, which is very my naming convention for my stuffed toys.

Travis Holland (1:00:52)

There’s just so many good names here. The Dino Nerd said Sizzle and Amy, which I love as well. Jack Perkins, who we’ve already mentioned. Do want to take this one?

Alyssa Fjeld (1:00:57)

He

he suggested Meg and Tilly, which is adorable as well.

Travis Holland (1:01:05)

My wife is named Meg. So don’t know if I can go with that one. Just just Josh E or aka BlueMorpho86 on Instagram suggested Izzy and scraps

Alyssa Fjeld (1:01:10)

Yeah, are you comparing her to the bug or the giant dinosaur? Tread carefully.

Adelle Pentland also suggested Esteban and Megara, which so fancy, so Spanish, and then so very Hercules, the animated series. Love that. We also got a suggestion on Instagram that I can’t find anymore because it was a reply to the story and I don’t know what happened to it, I’m sorry, but Jack Jones also made a suggestion. Jack, if you’re listening, please message me your suggestion.

Travis Holland (1:01:45)

Natalia Jagielska, an excellent paleontologist from, I think currently working in the UK, suggests… Yeah, incredible. She does some incredible work. Natalia. Suggests Bobo and Bebe, which is a nice cute pair. I like that one.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:01:52)

Such a fangirl of her work, my gosh. I have her sticker on my laptop.

Travis Holland (1:02:04)

Also over on Blue Sky, someone going by name of Goose Buster suggested Dino and Craig. And I just love the notion of Craig.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:02:12)

is so like one of my supervisors is named Craig as well which is so funny.

Travis Holland (1:02:16)

We have to be careful that people don’t think we’re naming it after them. But also, we didn’t suggest these names. We didn’t come up with this list ourselves. Edge, who is a science YouTuber, suggested Todd and Ruffles as well, which is a really good one. And there was one more suggestion from BlueSky, which was Khamira who suggested Barry and Bob.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:02:20)

Yeah.

No.

Travis Holland (1:02:36)

So just nice, simple Barry and Bob So how are we going to do this, Alyssa? How are we going to decide?

Alyssa Fjeld (1:02:36)

Bye.

I’m struggling so much because I think they’re all so fantastic and I don’t think I can pick just one. I think I could pick three and that could be… I could pick that many.

Travis Holland (1:02:51)

Mm-hmm.

Okay, so what if we pick three between us, three pairs, and we’ll put those up on Instagram for a final poll on the Fossils and Fiction Instagram account.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:02:57)

Yes.

I think that’s such a good idea. And then it’s out of our hands yet again, and the fabulous people who made these suggestions can help us one last time.

Travis Holland (1:03:13)

So we’ll poll it on Instagram and we will also poll it on the show’s Spotify page. think that’s probably a good place. So if you want to engage with us on Spotify, you can do it there or on Instagram. We will poll the three suggested pairs. So we need to go with, okay, I’m going to pick out Dave and Craig. And I think Dave for the trial of bite.

So this comes from one of Astrid’s suggestions and then Craig for the Australovenator

Alyssa Fjeld (1:03:41)

Thank you Goosebuster. And I think that’s so perfect. Like Dave, we had a colleague named Dave and I don’t want to say that he gives trilobite energy, but trilobites give Dave energy. Absolutely.

Travis Holland (1:03:52)

That’s one way to look at it.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:03:54)

promise this is not just a show of me negging my acquaintances. I love Scratch and Skitters. That’s so cute. it’s so cute. And then I don’t know, like my third pick would be Scuttle and Claw, but I have room in my heart for other suggestions if you really want to fight. Because like Tang and Tor also really, I like that as well. What do you think?

Travis Holland (1:04:03)

Scratch and Skitters from Jimmy Waldron yep.

Tang and Tor is really good too. I think as a pair. So this is going to be Astrid. Astrid’s come up with the goods here. We know how creative Astrid is, but Astrid’s got three names in the six. So, all right, Tang and Tor from Astrid. We’re going to put these and that’s going to be good because then Astrid’s vote won’t swing it too much because who knows which one they’re to go for.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:04:30)

Yeah.

Yeah, just think, yeah, those are such good choices and I’m so appreciative to everyone who wrote in. Thank you all so much.

Travis Holland (1:04:49)

Okay, Scratch and Skitters, Craig and Dave and Tang and Tor will go up on our Instagram and Spotify pages for a poll. We will compile the votes before our next episode and make a decision. And I think who the people who suggested these winners will make sure we get some stickers featuring the Australovenator and the Trilobite Estaingia Out to you.

We’ll make sure we get those in the mail. If your names are the suggested ones, the suggested winners. So I so look forward to naming these cute little critters

Alyssa Fjeld (1:05:22)

Yes, absolutely that and merch, the two best things in the world. And I might even, so my problem is buying a lot of stuffed animals and I might even use some of the ones we didn’t use for the show to name these other fabulous creatures behind me.

Travis Holland (1:05:34)

Yeah. I think we’re going to need somebody at some point to make them into stuffed animals.

Fossils And Fiction (1:05:39)

Travis dropping in post recording with an announcement to say that the next segment gets a little graphic. We talk about fighting prehistoric creatures and the various things they could do to a human. If you have sensitive ears listening into this episode, it might be best to skip ahead.

Travis Holland (1:05:59)

I’ve been listening to, PBS’s eons and in particular their new podcast series, which asks How would you survive?

in a past prehistoric era. And so they have a different episode focusing on various eras So the Carboniferous is one I was listening to this morning and there’s the Devonian and the Cambrian explosion. So all of these different eras. I suddenly thought what it sounds like to me when they’re doing the interviews. So they have the main host, Callie, and then they take somebody else from the PBS Eons team.

and they discuss how to survive the particular era. It’s a really, really cool podcast. Definitely worth checking out. But it sounded to me, I just keep picturing it as like, you know, like in a reality TV show, like Big Brother or something, they speak to the guests before they go into the house. And it’s like, what your strategy gonna be? How are you gonna win this thing? How are you gonna survive? And it sounds to me like the…

these chats that they have on the podcast is like that. Like how are you going to go in and survive? And then it’s missing the next step, right? Even though it’s so well researched and so interesting is like, I would love to see a paleo doc done like this, where these interviews on PBS Eons are like the introduction to

before they release somebody into the carboniferous.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:07:21)

It sounds like, so Ben Francischelli is a megalodon researcher here in Victoria. And he recently had an exhibit about priest work Bayside, which was a period of time when the Bomoras formation had megalodons and giant whales and all these like things that were out there that could totally kill you. And he filmed this short movie of himself fending off like Megs and things like it sounds.

Travis Holland (1:07:25)

You

Alyssa Fjeld (1:07:45)

I promise you it’s super cool and I would watch a full-length version of that any day. was like absolutely- and we all think- like I can’t say we all think about it, but we think about it. Palaeontologists think about it.

Travis Holland (1:07:58)

would you actually survive in this era? So for our version of this, the Fossils and Fiction version of PBS’s Eon Surviving Deep Time is going to be which prehistoric animal would you fight? We’ve got three categories. The first one, the one that I’m going to put to you is prehistoric mammals. So you have four potential contenders. You have to choose which of these you would have the best opportunity of fighting against. Megatherium

Alyssa Fjeld (1:08:00)

Yeah.

Okay.

Travis Holland (1:08:25)

which is a giant Grand Sloth from South America. It is an elephant-sized animal with massive claws, incredibly strong. It’s like imagine wrestling a living, breathing tree with murder mittens. So it’s not, you know, this is not the sort of slow-moving sloth that we think of. This is a dangerous beast.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:08:44)

Yeah.

Dense bones. If you see these guys at any of your local museums, you will notice that their bones are DENSE. And those murder mittens, he’s not kidding, the claws are ginormous.

Travis Holland (1:09:01)

that’s number one, the Megatherium. Number two is a Smilodon, your classic saber-toothed cat. This is like the size of a large lion with those massive canine teeth. It’s an ambush predator.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:09:15)

One of the strongest bite forces in the animal kingdom is my understanding.

Travis Holland (1:09:15)

If

Yeah. So teeth the size of steak knives is the thing that you’re contending with mostly here. Now, this might seem like a gimme, but I don’t think it’s as easy as you would think. And the next one I’ve come up with is diprotodon, the largest marsupial ever. We’ve had an episode or a couple of episodes where diprotodon has been mentioned. This is a car-sized wombat.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:09:36)

Classic.

Travis Holland (1:09:44)

probably weighs two tons, massive body weight with thick hide and thick fur. not to mention pretty gnarly front teeth. I think even though this is a herbivore, it could take a decent bite out of you in a fight. If you think you can take down a living tank, this is the one to pick. And finally, a dire wolf.

This is a larger than a modern wolf. I had the pleasure of going to the La Brea Tar Pits where they have a huge collection of dire wolf skulls earlier this year and to see them just laid out there, these are huge wolves. They pack hunt, they have extremely powerful bite.

Okay, what do you think out of those four? Megatherium, Smilodon, Diprotodon, or Direwolf?

Alyssa Fjeld (1:10:29)

it’s so tough. It’s so tough because, you know, like it depends on what your attack strategy is, I think, right? Like, are you whittling down the boss’s health bar Elden Ring style, or are you waiting to interrupt the attack pattern of the world’s most dangerous kitty? I saw the beautifully preserved, really intact Smilodon skeleton at the Smithsonian on my visit and my gosh, like

I think the thing that impressed me more than its ability to completely nosh my brain would be how small it was compared to how absolutely murderous this thing would have been. But I know in my heart of hearts, I couldn’t find a kitty. I could never find a kitty cat. I would just, I would give up. I would let it eat my face. I can’t, yeah.

Travis Holland (1:11:10)

Okay, so we’re gonna rule out the Smilodon.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:11:14)

And then I’ve been to a wolf sanctuary before. It’s just thinking like the thing that I think all of us are thinking, which like, coyotes aren’t that big. Wolves can’t be, they, they are that big. are, that thing would destroy my face. So out of the remaining two, I would have to say.

Travis Holland (1:11:30)

So we’ve got the ground sloth, the megatherium or diprotodon, sometimes called a giant wombat.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:11:35)

Hmm.

Travis Holland (1:11:37)

What would you go with? Now, one of the other reasons I had to put Diprotodon in here is I came across this extraordinary fact around the way they use their, this is actual wombats now, not Diprotodon as far as we know, the way they use their girthy rear to block the entrance to their burrows and potentially squash

any predators who try and come into the burrow against the roof of the burrow using their rear end.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:12:08)

Death by butt. Horrible. And like, no, this is true. This is all very true. There’s actually warning signs in areas with wombats to look out for them in your car because they will face your car with their butt like they would a predator. And your car is probably not gonna do great after that encounter. It will total your vehicle. It’s madness. I think out of those two, at least the diprotodon’s neck is not gonna have the same reach.

that the megatherium’s claws are gonna have. Like that swing radius, if you could get behind it on the neck. And I’m prefacing this by saying I would die no matter what. look at these arms, these are not like slaying mitts. I’m a delicate creature. But if I had to, would pick the diprotodon I’m sorry, Australia. This is why I you citizens.

Travis Holland (1:12:42)

You

well. So, Liz is gonna fight a protodon. If there’s anyone out there who would love to do some fan art of that, I’d love to see it.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:13:02)

Yeah, absolutely. No, I would pin it on my fridge. But I think it is now your turn to weigh in on a fight. Are you ready?

Travis Holland (1:13:12)

Yeah, go for it. Enjoy it. Yeah, go for it.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:13:14)

Okay, in this imaginary boxing ring, in one corner you have everyone’s favorite, the Velociraptor. A turkey-sized, much smaller than you would think based on the Jurassic Park movie, sharp, sickle-clawed, pack-hunting, intelligent murder chicken whose potential tagline, if he was on a poster, would be, technically smaller than you, but way more motivated.

Travis Holland (1:13:41)

I still think even though Velociraptor is smaller than the one in Jurassic Park, I still think of that Alan Grant line about using the claws to to gut you and then you are alive when they start eating you. And I just think that is so horrifying.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:13:54)

Yeah, and I mean, you know, turkey size… I like turkey size sounds reasonable at first, but like I challenge you to look up an American male turkey and ask whether you would even fight that creature.

Travis Holland (1:14:07)

mean, if you’ve ever had a goose chase you while you’re at a park or something, which I have, that would not be fun.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:14:12)

Mm-hmm.

In the other corner, taking up a significantly larger foot square space, you have everyone’s king of lizards, Tyrannosaurus rex, a bus-sized predator who has a massive bone-crunching bite and incredible sensory skills. The movie had it all wrong. If you hold still, he’s absolutely still gonna bite

Travis Holland (1:14:37)

I think we can rule out T. rex straight away. mean, ain’t nobody, nobody taking on a T. rex. Unless, the only real chance here, but it’s not exactly a fight, is just to run and maybe, maybe you could outrun it.

Alyssa Fjeld (1:14:47)

Yeah.

Yeah, outrun it or hope you pass by something that’s more delectable on the way out. You don’t have to be fast.

Travis Holland (1:14:53)