The Lost Canvas of Humanity: What the World Would Look Like If Paleolithic Rock Art Survived

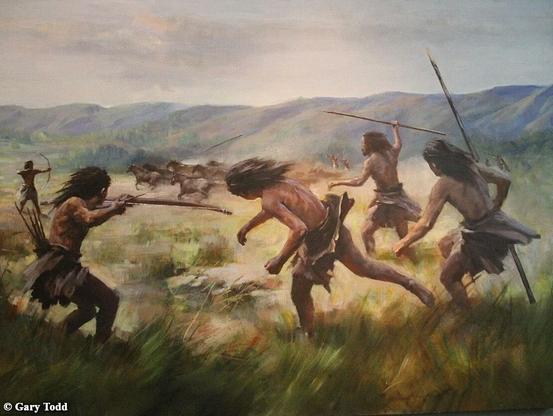

Imagine a world bursting at the seams with artwork—everywhere you turned, glimpses of ancient human expression etched into stone, painted onto cliffs, and adorning the landscapes around us. While this might sound like an exaggerated fantasy, it reflects the likely reality of the Paleolithic era. Today, we marvel at cave art like Lascaux or Chauvet because caves shielded these masterpieces from the harsh effects of weather and erosion. But beyond the shelter of caves, an abundance of open-air rock art once existed—now largely lost to the relentless march of time.

Beyond the Cave Walls: A Broader Artistic Tradition

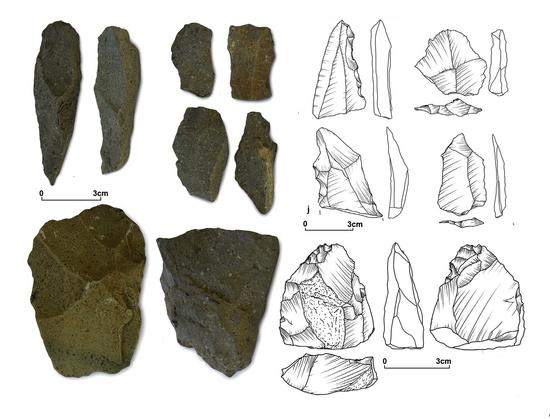

Rock art, a powerful testament to early human creativity and communication, wasn’t confined solely to caves. Throughout the Paleolithic, artists frequently chose open spaces—cliff faces, boulders, and rock outcrops—to share their stories, express their spirituality, mark territories, or simply beautify their surroundings. Unfortunately, these exposed locations meant their artwork was far less likely to survive thousands, or even tens of thousands, of years.

The Erosion of Evidence

One primary reason for the scarcity of surviving open-air rock art is weathering. Unlike cave interiors, exposed rock surfaces face constant assault from sun, wind, rain, temperature fluctuations, and biological growth. Over millennia, these natural forces gradually erase delicate pigments and detailed carvings. In temperate climates, freeze-thaw cycles accelerate this destruction, cracking rocks and further obliterating ancient imagery.

A Glimpse at What Survived

Consider the Coa Valley in Portugal—an area renowned for its surviving open-air Paleolithic rock art, which escaped obliteration due to a unique combination of geological stability and relatively arid conditions. These circumstances are rare, which explains why such rich open-air art sites are uncommon. Yet discoveries like those in the Coa Valley hint at the vast quantities of rock art that likely existed in other, less forgiving environments.

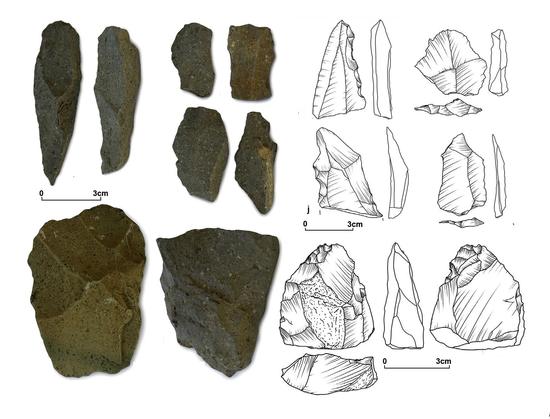

At one of three sites where the public may take a guided jeep and walking tour, an auroch is plainly visible, deeply outlined with a pecking technique using a flint or quartz tool. Dillon von Petzinger

A Lost World of Art

If open-air rock art had preserved more effectively, our understanding of prehistoric peoples would be dramatically deeper. We would likely find that art wasn’t an occasional endeavor, limited to deep and inaccessible caves, but rather an integral, ubiquitous aspect of daily Paleolithic life. Imagery would adorn riverbanks, mountain passes, pathways, hunting grounds, and ceremonial sites—transforming our modern landscapes into immense outdoor galleries.

Expanding the Canvas of Human Culture

Furthermore, widespread rock art could profoundly impact our understanding of early human cognition and culture. A greater volume of preserved artworks would provide more data points, revealing regional differences, thematic patterns, stylistic evolutions, and the diffusion of cultural ideas across vast geographic distances. This artistic abundance would clarify questions about human migration, interaction between groups, and cultural development.

Lessons from Australia

Consider Australia, home to some of the oldest continuously practiced artistic traditions in the world. There, open-air rock art has survived remarkably well due to relatively stable environmental conditions. Australia’s extensive rock art offers insights into complex belief systems, social structures, and historical events spanning tens of thousands of years. Had similar preservation conditions existed elsewhere, the Paleolithic world would similarly unveil its hidden stories, offering us intricate snapshots of long-gone societies.

Rethinking the Human Story

If Paleolithic rock art had survived globally, the cultural narrative we tell ourselves today would differ dramatically. Art has always been a mirror of society, reflecting its values, struggles, joys, and spiritual insights. With broader preservation, we would see far more nuanced and diverse stories from the past. Instead of isolated masterpieces, we’d discover continuous, evolving narratives of human existence, resilience, and imagination.

The Beauty of Impermanence

While we lament the loss of this invaluable heritage, there’s a poignant beauty in acknowledging its impermanence. The Paleolithic artists likely understood the transient nature of their creations, crafting images with passion, perhaps aware that their expressions might only briefly withstand the elements. This impermanence connects us to them in a profoundly human way—reminding us of life’s fleeting beauty and the universal drive to communicate, to express, and to leave a mark, however temporary.

The Côa River’s present-day route is virtually unchanged from its Ice Age flow, making it easy to visualize the landscape as our ancestors saw it. Dillon von Petzinger

A World That Could Have Been

In the end, the missing rock art of the Paleolithic era is a tantalizing glimpse into what might have been. Imagining a world brimming with ancient artistic expression inspires awe and wonder, driving home the profound truth that humanity’s artistic impulse is deep-rooted, boundless, and resilient—even when confronted by nature’s inevitable erasure.

#AncientArt #Anthropology #Archaeology #ArtHistory #ArtPreservation #AustraliaRockArt #CaveArt #CoaValley #CulturalHeritage #EarlyHumans #HumanCreativity #HumanHistory #Impermanence #OpenAirArt #PaleolithicArt #PrehistoricArt #RockArt #StoneAge