What Happened Before History? Human Origins

#EarlyHumans

A Touch Across Time: The Neanderthal Fingerprint That Changed Everything

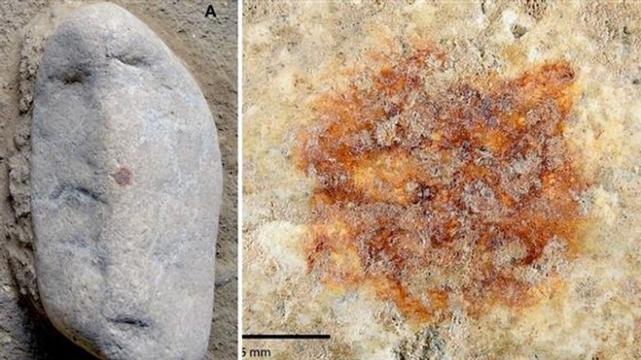

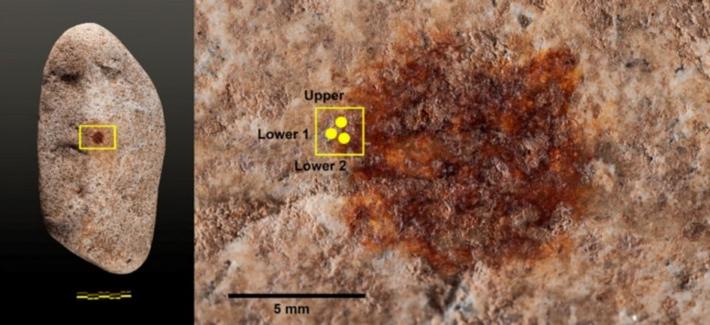

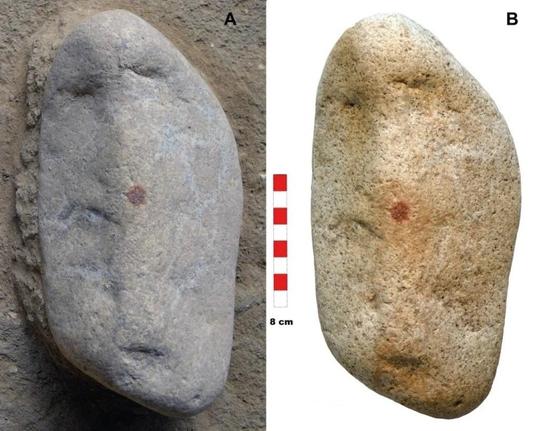

In the quiet, sun-dappled hills of San Lázaro, Spain, archaeologists recently stumbled upon an astonishing discovery—a simple red ocher fingerprint pressed deliberately onto a rock surface some 43,000 years ago. At first glance, this may seem humble: a fleeting human mark from deep history. But this fingerprint is far more profound. It belongs not to Homo sapiens—modern humans like you and me—but to our enigmatic cousins, the Neanderthals (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2024).

This tiny imprint is more than just an ancient mark. It’s a tangible, intimate connection to a Neanderthal individual, someone who stood exactly where researchers now stand, touching a stone in a purposeful act. So, what exactly does this discovery mean for our understanding of Neanderthals? Why is it so exciting, and why should it captivate us?

A Moment Captured in Time

Consider, for a moment, the sheer wonder of a fingerprint. Every single ridge and swirl is unique to an individual—a personal signature no one else shares. This particular Neanderthal fingerprint, vividly preserved in red ocher, offers an intimate snapshot from tens of thousands of years ago. The decision to press one’s finger onto the rock, leaving a deliberate mark, strongly suggests intentionality and symbolic expression (Zilhão, 2012).

Previously, many viewed Neanderthals as primarily practical, survival-focused beings who didn’t engage significantly in symbolic thought. Over recent decades, however, discoveries like shell jewelry, cave art, and now this fingerprint have profoundly reshaped that narrative. This fingerprint suggests a conscious, meaningful action—a symbolic gesture that hints at complex thought processes and an awareness of self and identity (d’Errico & Stringer, 2011).

Symbolism and Self-Awareness

When modern humans use art, we communicate ideas, emotions, or stories. Could the same be true for Neanderthals? The placement of the fingerprint wasn’t random; the stone was naturally shaped somewhat like a face. By enhancing its facial features with this print, the Neanderthal artist was engaging in representational thought, transforming a naturally occurring shape into something more—a representation with meaning beyond mere practicality.

This find challenges earlier assumptions about Neanderthal cognition, pushing the boundary of what we define as distinctly “human.” Symbolic behavior and self-awareness have often been considered hallmarks of modern human cognition. Finding evidence of this behavior in Neanderthals suggests that they shared far more cognitive and cultural complexity with us than previously thought (Hovers & Belfer-Cohen, 2013).

What We’ve Learned So Far

This single fingerprint can tell us a surprising amount. Forensic analysis has determined that it belonged to an adult male, offering a glimpse into the demographics of the site (Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2024). Its remarkable preservation provides clues about Neanderthal material culture. Ocher, a naturally occurring mineral pigment, was clearly valued, collected, and used deliberately.

Studies of ocher use among both modern humans and Neanderthals show it was often employed in rituals, personal adornment, and symbolic contexts. Its presence on this stone strongly supports the interpretation of symbolic intent rather than mere practicality (Wadley, 2005).

New Avenues of Research

Where do we go from here? First, archaeologists can explore other Paleolithic sites with fresh eyes, looking for subtle symbolic marks or impressions previously overlooked. Discoveries like this fingerprint remind us that symbols and meaning-making activities may not always be grandiose. Sometimes, they’re understated yet powerful.

Second, interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial. Forensic science, pigment analysis, cognitive archaeology, and ethnography must come together to illuminate the broader context of such symbolic acts. Was this mark part of a social ritual or a personal statement? Did ocher carry particular cultural significance?

Third, this discovery encourages us to re-evaluate the archaeological record holistically. Perhaps other seemingly mundane artifacts conceal symbolic dimensions. Staying open to subtle details might reveal hidden narratives and richer cognitive worlds.

Implications for Science and Humanity

Archaeology thrives on asking better questions. Once, the core question about Neanderthals was whether they had symbolic capacity at all. Now, the focus shifts: What form did their symbolic behavior take? How widespread was it? What role did symbolism play in their social fabric?

This find also highlights the importance of site preservation and meticulous excavation. The fingerprint survived thanks to extraordinary preservation conditions—conditions increasingly threatened by climate change and human activity.

Importantly, this discovery prompts us to rethink human uniqueness. If symbolic expression developed independently in different hominin species, then symbolism may not be a rare cognitive anomaly but a fundamental aspect of hominin brain evolution. This challenges longstanding assumptions about our exclusive grip on culture and art.

Bridging the Millennia

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of this discovery is its intimacy. A fingerprint bridges tens of thousands of years, connecting two individuals across an unimaginable gulf of time. It evokes empathy, curiosity, and awe. We glimpse, however briefly, the emotional and intellectual world of a person long gone.

The emerging picture of Neanderthals is one of nuance and richness. They were not brutish outliers of evolution but thoughtful, creative beings with lives filled with meaning. This fingerprint deepens that narrative and elevates our appreciation for the breadth of human experience.

Final Reflections

The red ocher fingerprint from San Lázaro is a potent reminder that history is made not only through tools and bones but through the quiet, deliberate gestures of individuals. This ancient mark redefines what it means to be human and extends our story beyond the borders of Homo sapiens.

As scientific inquiry continues, each new discovery—no matter how small—adds to our collective understanding. The fingerprint from San Lázaro is a vivid testament that every one of us leaves an impression. Some fade. Some, like this, endure.

Let it inspire us to keep asking questions, stay curious, and embrace the deep history that connects us all.

References:

d’Errico, F., & Stringer, C. (2011). Evolution, revolution or saltation scenario for the emergence of modern cultures? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1567), 1060–1069. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0303

Hovers, E., & Belfer-Cohen, A. (2013). On variability and complexity: Lessons from the Levantine Middle Paleolithic record. Current Anthropology, 54(S8), S337–S357. https://doi.org/10.1086/673389

Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A., et al. (2024). Neanderthal fingerprint on ochre-enhanced stone at San Lázaro, Spain: Symbolic behavior in the Middle Paleolithic. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-01876-2

Wadley, L. (2005). Putting ochre to the test: Replication studies of adhesives that may have been used for hafting tools in the Middle Stone Age. Journal of Human Evolution, 49(5), 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.06.007

Zilhão, J. (2012). Personal ornaments and symbolism among the Neanderthals. In J.-J. Hublin & M. P. Richards (Eds.), The Evolution of Hominin Diets (pp. 35–49). Springer.

#AncientMind #AnthropologyMatters #Archaeology #CaveArt #CognitiveEvolution #DeepHistory #EarlyHumans #HomininCulture #HumanOrigins #Imagination #Neanderthal #NeanderthalArt #Paleoanthropology #Paleolithic #PaleoPost #PaleoPostDeepHistoryNeanderthalArtCaveArtAnthropologyMattersScienceCommunicationHomininCultureCognitiveEvolutionPrehistoricExpression #PrehistoricArt #RockArt #ScienceCommunication #SymbolicArt #earlyHumans #evolution #genetics #history #Science

4:36am Tentacles by Early Humans from A Wave

#KJAC #TheColoradoSound #EarlyHumans

The Lost Canvas of Humanity: What the World Would Look Like If Paleolithic Rock Art Survived

Imagine a world bursting at the seams with artwork—everywhere you turned, glimpses of ancient human expression etched into stone, painted onto cliffs, and adorning the landscapes around us. While this might sound like an exaggerated fantasy, it reflects the likely reality of the Paleolithic era. Today, we marvel at cave art like Lascaux or Chauvet because caves shielded these masterpieces from the harsh effects of weather and erosion. But beyond the shelter of caves, an abundance of open-air rock art once existed—now largely lost to the relentless march of time.

Beyond the Cave Walls: A Broader Artistic Tradition

Rock art, a powerful testament to early human creativity and communication, wasn’t confined solely to caves. Throughout the Paleolithic, artists frequently chose open spaces—cliff faces, boulders, and rock outcrops—to share their stories, express their spirituality, mark territories, or simply beautify their surroundings. Unfortunately, these exposed locations meant their artwork was far less likely to survive thousands, or even tens of thousands, of years.

The Erosion of Evidence

One primary reason for the scarcity of surviving open-air rock art is weathering. Unlike cave interiors, exposed rock surfaces face constant assault from sun, wind, rain, temperature fluctuations, and biological growth. Over millennia, these natural forces gradually erase delicate pigments and detailed carvings. In temperate climates, freeze-thaw cycles accelerate this destruction, cracking rocks and further obliterating ancient imagery.

A Glimpse at What Survived

Consider the Coa Valley in Portugal—an area renowned for its surviving open-air Paleolithic rock art, which escaped obliteration due to a unique combination of geological stability and relatively arid conditions. These circumstances are rare, which explains why such rich open-air art sites are uncommon. Yet discoveries like those in the Coa Valley hint at the vast quantities of rock art that likely existed in other, less forgiving environments.

At one of three sites where the public may take a guided jeep and walking tour, an auroch is plainly visible, deeply outlined with a pecking technique using a flint or quartz tool. Dillon von PetzingerA Lost World of Art

If open-air rock art had preserved more effectively, our understanding of prehistoric peoples would be dramatically deeper. We would likely find that art wasn’t an occasional endeavor, limited to deep and inaccessible caves, but rather an integral, ubiquitous aspect of daily Paleolithic life. Imagery would adorn riverbanks, mountain passes, pathways, hunting grounds, and ceremonial sites—transforming our modern landscapes into immense outdoor galleries.

Expanding the Canvas of Human Culture

Furthermore, widespread rock art could profoundly impact our understanding of early human cognition and culture. A greater volume of preserved artworks would provide more data points, revealing regional differences, thematic patterns, stylistic evolutions, and the diffusion of cultural ideas across vast geographic distances. This artistic abundance would clarify questions about human migration, interaction between groups, and cultural development.

Lessons from Australia

Consider Australia, home to some of the oldest continuously practiced artistic traditions in the world. There, open-air rock art has survived remarkably well due to relatively stable environmental conditions. Australia’s extensive rock art offers insights into complex belief systems, social structures, and historical events spanning tens of thousands of years. Had similar preservation conditions existed elsewhere, the Paleolithic world would similarly unveil its hidden stories, offering us intricate snapshots of long-gone societies.

Rethinking the Human Story

If Paleolithic rock art had survived globally, the cultural narrative we tell ourselves today would differ dramatically. Art has always been a mirror of society, reflecting its values, struggles, joys, and spiritual insights. With broader preservation, we would see far more nuanced and diverse stories from the past. Instead of isolated masterpieces, we’d discover continuous, evolving narratives of human existence, resilience, and imagination.

The Beauty of Impermanence

While we lament the loss of this invaluable heritage, there’s a poignant beauty in acknowledging its impermanence. The Paleolithic artists likely understood the transient nature of their creations, crafting images with passion, perhaps aware that their expressions might only briefly withstand the elements. This impermanence connects us to them in a profoundly human way—reminding us of life’s fleeting beauty and the universal drive to communicate, to express, and to leave a mark, however temporary.

The Côa River’s present-day route is virtually unchanged from its Ice Age flow, making it easy to visualize the landscape as our ancestors saw it. Dillon von PetzingerA World That Could Have Been

In the end, the missing rock art of the Paleolithic era is a tantalizing glimpse into what might have been. Imagining a world brimming with ancient artistic expression inspires awe and wonder, driving home the profound truth that humanity’s artistic impulse is deep-rooted, boundless, and resilient—even when confronted by nature’s inevitable erasure.

#AncientArt #Anthropology #Archaeology #ArtHistory #ArtPreservation #AustraliaRockArt #CaveArt #CoaValley #CulturalHeritage #EarlyHumans #HumanCreativity #HumanHistory #Impermanence #OpenAirArt #PaleolithicArt #PrehistoricArt #RockArt #StoneAge

New research highlights key differences in burial practices between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens. While both exhibited care for their dead, the contrasting rituals offer a glimpse into their distinct cultural and cognitive worlds. What do these differences reveal about our shared human ancestry? #Neanderthals #EarlyHumans #Archaeology

https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/neanderthals-and-early-homo-sapiens-buried-their-dead-differently-study-suggests

Neighbors...

Muddy footprints suggest 2 species of early humans were neighbors in Kenya 1.5 million years ago

Muddy footprints left on a Kenyan lakeside suggest two of our early human ancestors were nearby neighbors some 1.5 million years ago.

The footprints were left in the mud by two different species “within a matter of hours, or at most days,” said paleontologist Louise Leakey, co-author of the research published Thursday in the journal Science.

Where are the articles that notice the advent of saliva that breaks down starch are at the same time when early humans began baking bread?

Cruelty is not the default.

#Neanderthals #evolution #society #people #EvolutionaryPsycholgy #EvolutionaryPsychologists #EarlyHumans #DownsSyndrome #cruelty #love #default

The world's oldest cave paintings are in Indonesia, and the oldest is 51,200 years old. (The runner-up, 6 miles away, is 45,500 years old.)

#archaeology #anthropology #Indonesia #CavePainting #science #EarlyHumans

When I was visiting the Cradle of Humankind museum here in SA last week I was telling my friend about the Denisovans and the interesting discoveries about them and was showing a bit of it on my phone. Now my phone adds Denisovan news to my usual mix of recommended articles which I'm not entirely mad about😂📜

#Denisovans #EarlyHumans

https://www.livescience.com/health/genetics/papua-new-guineans-genetically-isolated-for-50000-years-carry-denisovan-genes-that-help-their-immune-system-study-suggests

A Siberian site reveals early human habitation dating back 417,000 years, making it the most ancient northern settlement discovered. This discovery reshapes our understanding of when humans first reached high latitudes. #HistoryUncovered #EarlyHumans #evolution #humanity

The Plant-Based Origins of Early Human Diets

Discover the plant-based truth behind the Paleo diet based on new archaeological findings, challenging the myth of early humans' meat-heavy eating habits.

#ancestraldiet #archaeologicaldiscoveries #earlyhumans #nutrition #Paleodiet #plantbased #vegan24news #veganism

https://vegan24.news/the-plant-based-origins-of-early-human-diets/

The problem with unending hair growth for early humans, is that it would literally trip up our ancestors. This could spell trouble both when running from predators and running in when killing prey.

Indeed, back then, I bet baldness was prized. So too would be hair breakage before the hair gets too long. While both are seen as a problem by some today, they could have literally saved your life back in the stone age.

The one advantage of unending hair growth is that it might take decades to become as long as its person. It could be like an old age pension. If you’re so old that you trip over your hair, then you can stay home and do lesser tasks than hunting. The rest of the clan would have to hunt and forage for you.

So it is my bet, that the first thing that stone tools were developed for, would have been to cut our hair. If you were going back in time to such an era, you could bring along a good pair of scissors. They might be prized over other tools.

I envision the first tools may have been a stone that came to a point. This way, you could put the hair to be cut against flat rock and bash the sharp end of the stone against the hair. This would have been both the first barbershop and the first hair salon.

Only after making the tool to cut hair would we realize it had other uses. Like to kill and skin prey, So I am thinking this may have been the very first tool that humanity made and used, So the first profession after forager might have been the barber or hairdresser.

https://larryrusswurm.com/2023/12/23/unending-hair-growth/

#baldnessPrized #barber #earlyHumans #firstTool_ #forager #hairSoLongItTrips #hairdresser #likeAnOldAgePension #runningAfterPrey #runningFromPredators #stayHomeWhileClanForages #unendingHairGrowth

New Scientist

Our ancestors may have come close to extinction 900,000 years ago

A genetic analysis suggests our ancestral population fell as low as around 1300 individuals nearly a million years ago, but other experts aren't convinced

The population of our ancestors may have plummeted to as low as 1300 around 900,000 years ago, possibly as a result of our ancestral species splitting from other early humans.

Did early humans interbreed? These scientists made a map to prove it. They used climate simulations and genetic data to show how Neanderthals and Denisovans met and mingled in different regions and periods. Their findings reveal how climate change influenced the evolution and diversity of our ancient ancestors.

300,000-Year-Old Weapon Reveals Early Humans Were Woodworking Masters

New research on a 300,000-year-old throwing stick reveals advanced woodworking techniques among early humans, suggesting communal hunting practices involving the whole community. The artifact, demonstrating high craftsmanship, indicates early humans’ deep knowledge of wood properties.

https://scitechdaily.com/300000-year-old-weapon-reveals-early-humans-were-woodworking-masters/ #EarlyHumans #woodworking #ThrowingStick #craftsmanship

Thinking about how humans once lived in balance with their environment while still being utterly human.

Referenced link: https://phys.org/news/2023-06-life-air-conditioning-curly-hair.html

Discuss on https://discu.eu/q/https://phys.org/news/2023-06-life-air-conditioning-curly-hair.html

Originally posted by Phys.org / @physorg_com: http://nitter.platypush.tech/physorg_com/status/1666492481590943764#m

Life before air conditioning: #Curlyhair kept #earlyhumans cool, says study @penn_state @PNASNews https://pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2301760120 https://phys.org/news/2023-06-life-air-conditioning-curly-hair.html

Referenced link: https://phys.org/news/2023-05-dangers-early-humans-life-threatening-flintknapping.html

Discuss on https://discu.eu/q/https://phys.org/news/2023-05-dangers-early-humans-life-threatening-flintknapping.html

Originally posted by Phys.org / @physorg_com: http://nitter.platypush.tech/physorg_com/status/1661780418029400081#m

Despite the dangers, #earlyhumans risked life-threatening flintknapping injuries @kentstate https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-antiquity/article/injury-costs-of-knapping/38646F8580956D68F2AFFDD9C98DD8B4 https://phys.org/news/2023-05-dangers-early-humans-life-threatening-flintknapping.html

Stone flakes made by modern monkeys trigger big questions about early humans https://flip.it/S2mEMk #Monkeys #EarlyHumans