Wie lässt sich denn Englisches #Kreol ((Tok Pisin #tokpisin)) übersetzen 🤷♀️

Gibts n Tipp?

Mich würde der Textinhalt (Hans Zimmer/ Thin Red Line) „God Yu Tekkem Laef Blong Mi“ interessieren -

#TokPisin

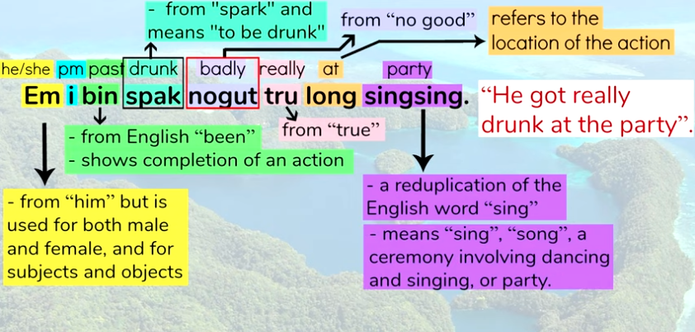

... und dann waren da noch die "Creol-Sprachen", wie hier "Tok Pisin", das sich u.a. von englischen und deutschen Wörtern ableitet, aus Zeiten der Kolonisation.

"Em i bin spak nogut tru long singsing"

=

"He/She got really drunk at the party."

(Reiner Zufall, dass ich dieses Beispiel verwende ;)

#TokPisin #CreolLanguage #Language #LearnLanguages

“Eat shit” and “Oh fuck”: Sweary First and Last Words in Michael Erard’s “Bye Bye I Love You”

We will not go gentle into that good night here at Strong Language. We will rage. Oh, we will rage, all right, uttering our shit’s, fuck’s, and damn’s until the bitter-ass end.

And that’s true for a lot of us, according to Michael Erard in his latest book, Bye Bye I Love You: The Story of Our and First Last Words, out now from the MIT Press. Apparently some of us even come into speech, let alone leave it behind, kicking and screaming—and swearing!

The story of first and last words that Erard, a linguist and author, tells in Bye Bye I Love You is intelligent, humane, cross-disciplinary, beautifully written, and comprehensive, offering a historical and cultural account of our first and final utterances as much as a linguistic one.

Germane to my fellow vulgarians here, I was fascinated to learn that cursing does have a place amid the mama’s and famous last words we associate with our initial and ultimate speech acts. (And as Erard well explains, these verbal bookends are indeed far more complex than those associations.)

Bye Bye I Love You by Michael Erard (2025, MIT Press)Erard’s research shows that we are far quieter in our dying, and, when actually observed, the substance of our speech is far more ordinary than we, the surviving, might otherwise expect or desire. That’s in large part because so many of us are living longer—and dying in medicalized circumstances, afflicted with multiple conditions that limit our cognitive, physical, and thus linguistic capacity. We may well be delirious if not already unconscious.

Still, Erard identifies patterns. Answering the question of “Will approaching death change the shape of my utterance?” in his chapter “A Linguistics of Last Words,” he explains:

When people do speak, they call out: people’s names, curses, religious phrases. They state the obvious (“I’m dying”). They ask questions with sadly obvious answers (“Am I dying?”) … They direct a carer to do something mundane (“Take off my mask”; “Lift up my head”; “Water”); these utterances resemble the action schemes of first words. Sometimes they bid farewell (“I’m done”) or demand release (“Let me out of here”), as they’re leave-taking in the literal sense. They can be unfailingly polite (“thank you”). Yet from a doctor I heard that Anglophones often say, “Oh fuck oh fuck.” This is because cursing has a well-documented analgesic effect; actual vulgarities relieve more pain than made-up ones. Yet vulgarity and transgression are culture-specific, so the experienced person might encounter a variety of curses, to be matched with Samoan babies’ first words (“shit!”) As to whether or not a dying person swears more (or does any other linguistic behavior), the only way to tell is if you know how often they swore before. Which is something few of us are able to say with objective certainty.

Present company excluded, of course.

There is something intuitively palliative about end-of-life profanity. Yes, swearing puts the anal in analgesic (wait, that’s not how that word works); it can help reduce the sensation of pain, as Erard noted. But we would expect swearing, too, seeing that this class of language functions to help give expression to intense emotions, inter alia. And what is more intense than death? “[T]he brain reserves a special place for words with emotional associations, something that the names of loved ones and curses both share,” Erard writes.

But Erard goes further, contextualizing cursing within an initial paradigm he sketches for our last language. I quote at length (paragraph-initial bolding is his, other bolding is mine to transpose his original italics not rendered in formatting here; sic passim):

Final utterances are likely to be short. Without knowing what was linguistically typical for an individual, it’s impossible to say what changed for them. One thing that’s reasonable to say about final spoken utterances is that they’re shorter than the ones a person would typically use. Curses, names, imperatives, interjections: these are all short, one or two words. So are moans (if one includes them as behaviors that can be last words) and cries. This may seem like an unsubstantial conclusion, but linguists often consider utterance length, which immediately opens the door to considering what remains of syntactic complexity. …

Final utterances are likely to be disinhibited. Even if they aren’t outright delirious, people who are known to be discreet or proper may say things they wouldn’t have before. They might curse, comment on someone’s appearance, or accuse someone of a bad act. But this is to be expected, as one of the functions of the brain’s cortex is to inhibit behaviors and attention, and its failure means its inhibitory powers fall away. The neurochemical commotion in the dying brain will have less effect on the limbic system at first. Consequently, such limbic vocalizations as emotionally charged language, exclamations, and cursing have fewer impediments to expression. …

Final utterances are likely to be formulaic. It’s likely that the laissez parler [“say what you will”; unscripted] last word has been used before with some frequency, an aspect of language at the end of life that has escaped notice so far. Many last words like these reported anecdotally … fall into the category of “formulaic language,” which researchers have defined as “conversational speech formulas, idioms, pause fillers, and other fixed expressions known to the native speaker.” In English, these are utterances like “I love you,” “Thank you,” “Can I go?” “I’m going,” Cheerio,” “My dear wife,” “Amen,” “Oh God,” “Oh fuck.”

Erard goes on to explain that formulaic language—which is more familiar, automatic, and recallable—does a lot of heavy lifting for us both cognitively and communicatively. And when we’re dying, our cognitive capacity is low but our need to communicate is high.“ Thus, at the end of life,” he writes, “formulaic language shows up as prayers, other religious language, expressions of affection and relationship, and other words or phrases a person might have used a lot in their lives, including names and curses.” He continues that “if you want to have a prayer, a sacred phrase, or a deity’s name on your lips in your final moments,”—or, you know, a refulgent F-bomb— “it helps to practice well in advance of the deathbed, ideally for most of your life.”

We need no further encouragement to rehearse our moribund motherfucker’s, Michael.

For his part, Erard told me in an email that he submitted an abstract to the 2025 international conference on the f-word, positing fuck as “an ideal last word” due to “some psycholinguistic properties that give it some advantages in some end of life circumstances.” (Yes, there very much is such a so-called WTF Conference, and this year will feature keynotes from Strong Language’s very own Jonathon Green and Jesse Sheidlower as well as Tony McEnery.)

Erard includes a fourth element to his framework for our lives’ closing remarks: people will communicate differently with different partners. Here, he cites moving examples of intimate nonverbal communication from people who have variously lost speech in their final moments. My incorrigibly irreverent mind, of course, is surmising sweary scenarios.

Now, to rewind the lifespan to first words, a topic where I, for one, was surprised to learn swearing pertains. We wouldn’t want babies, now would we, to mark this moment in their languagehood with some vulgar vocable? Oh, their frickin’ ears! Oh, their precious, toothless, frickin’ slavering little mouths!

But my surprise, as it happens, precisely reinforces one of Erard’s main points—what we count, even condition, as first words is a product of cultural expectations. As he puts it, “a first word is less something that a baby produces and more something that babies and adults do together.”

The phenomenon, however, is ostensibly by no means widespread. One user on Bluesky, for what it’s worth, shared that his first word was “bugger.” In my own family, there is lore that my uncle’s first word was fockengock—a nonsense term he used to signify “water” and which he and my mother embraced as a sometime minced oath. Keep practicing, Uncle, and you can make it your last! Maybe, dear fucking reader, you have your own sweary first word tale to recount? Pray tell,

(Fockengock: does such gibberish even count as a first word? This is exactly the kind of question Erard deftly unpacks throughout Bye Bye I Love You. And if you’re curious, the ten most frequent first words in American English, according to one important study, were: “mommy,” “daddy,” “ball,” “bye,” “hi,” “no,” “dog,” “baby,” “woof woof,” and “bananas.” Many of these are frequent in many other languages as well. And to be sure, the topic of children’s first swear words is one for a different day.)

But the phenomenon is not unheard of. Which leads us to the Samoan “shit!” alluded to before. Erard cites influential fieldwork on infant language learning by linguistic anthropologist Elinor Ochs:

As a young mother herself, [Ochs] spent time studying children in Western Samoa in the 1970s and 1980s, carefully portraying how the baby interacts with many caregivers: not just a mother but other children and female family members (though rarely fathers). Ochs noted that Samoan concepts of natural behavior (amio) and socially appropriate behavior (aga) preside over how infants and caregivers react. Samoans tolerate behavior in children that would be considered a disciplinary problem from the Western point of view—running and shouting during church services, throwing stones at caregivers, hitting siblings—because children aren’t able to control amio nor adequately perform aga.

It is in this context that Ochs related Samoans’ emblematic first word, which is a shortened version of a longer curse, “ai tae,” meaning “eat shit.” This word embarrassed the Samoan mothers, at least when they mentioned it to Ochs, even though it confirmed a socially acceptable view that children are ruffians, unfit for social interaction, and even though the children didn’t actually know the meaning of tae. Yet saying “shit” for the first time confirmed that the young child was indeed fitting the template of what young children do.

In his notes, Erard directly quotes from Ochs, worth sharing here as much for the additional context as learning more about how Samoans think and talk about swearing:

When we asked why young children produced tae as their very first word, we were told that very young children palauvale (“use bad or indecent language”) or ulavale (“make nuisance of oneself, make trouble”) … In other words, this is the nature of children.

Because children act like little shits, of course they are going to say “shit.” Erard raises this example from Samoa not to gawk at how exotic or different the culture is from the West. Again, he uses it to emphasize that first words are culturally constructed, not natural or universal—parents and caregivers extract them from babbling as emblematic of cultural beliefs and values, as “a prescribed verbal form that human babies must produce as the threshold that grants them personhood.” This is as true of shit, he argues, as mama, which reflects culturally specific beliefs and rituals surrounding the mother-child bond, the primacy of the domestic sphere, and, yes, gender dynamics in society.

🤬 In his 2016 book What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains, and Ourselves, author Benjamin K. Bergen also covers Ochs’s research on the Samoan shit-y first-word, as previously excerpted and reviewed on the blog.

Finally, Erard cites field studies by Don Kulick, a linguistic anthropologist who has worked, among other places, in Gapun, a small and isolated village and community in Papua New Guinea whose people speak a disesteemed language, Tayap, along with the creole Tok Pisin.

Kulick observed that a child’s first word in Tayap, among other variations on the theme, was okɨ, pronounced like “okuh” and meaning “I’m out of here”—almost more adolescent than infantile, which corresponds to the Gapun view that children are “emotionally bristly and definitely antisocial.” (I mean, can you blame them? Adults are the worst.)

Kulick added that Gapun adults don’t exactly converse with children, holding the view that such an enterprise is futile. However, Erard goes on:

… children do get enough interaction to realize that everyone is constantly lying to them—in Kulick’s account, village life consists of a surprisingly large amount of low-grade, overlapping and mutual gaslighting—as well as enough exposure to obscenity that Kulick suggested that children’s real first words are two Tok Pisin phrases, “kaikaikan” (“eat cunt”) and “giaman” (“that’s a lie”).

I’ll let that prospective first word, kaikaikan, be my last.

🤬 For more on swearing in Gapun and Kulick’s research there, revisit Stan Carey’s “‘Pigs knock you down and fucking fuck you’: the obscene language of the kros.”

Discover so much in Michael Erard’s incisive, affecting, and sometimes sweary achievement, Bye Bye I Love You, published by the MIT Press and available from your preferred booksellers. The publisher sent me a copy for review on my etymology blog, Mashed Radish, during which reading I was compelled to discuss the topic of swearing in first and last words for this blog.

#anthropology #books #cunt #death #firstWords #fuck #Gapun #languageLearning #lastWords #MichaelErard #Samoa #shit #sociolinguistics #Taiap #Tayap #TokPisin

Chilly outside, but sunshine through my speakers. This is Tonton Malele & Nene Morus, feat. Jayrex Suisui with Pikinini Niu Ailan. #Music from #PapuaNewGuinea, more specifically new Ireland. This is the lyric video in case you want to see how much you can follow of the words in #TokPisin, though I think it includes an Austronesian #language (of which there are many) as well.

This is not music I normally listen to, but when the mood strikes, definitely!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKmYElPBz4M

A few fun verbs from #TokPisin :

* kamap = "comes up" (evidently being born or brought up)

* wokabaut = "walk about"

* raitim = "write it"

My favorite, from "orait" = "all right":

Jisas i-oraitim sikman = "Jesus heals a sick man" (i.e. made him all right)!

I don't know Tok Pisin, so it's a bit like flipping through someone else's photos looking for my own friends wearing different clothes and hairstyles.

3/ (maybe more, maybe not)

The creole language Tok Pisin presents English speakers with a fun game of recognizing words, since so many of them are derived from English, but spelled phonetically.

From my mother-in-law, I received an old Bible summary entitled "Sampela Tok Bilong Baibel" = "Some Bible Talks"

Atam na Iv = Adam and Eve

Ken na Epel = Cain and Abel

Lo bilong God = God's Law

"Tupela Rot" confused me until I saw "Rot long Dai" and "Rot long Laif" (Two Roads, Road to Death, Road to Life).

#TokPisin #Bible

so i can't even blame Latin?

what is singular in Latin?

Though, from what little I know of #Latin #grammar all I've learned is that Latin is crazy and that I don't want to learn it.

#TokPisin seems to have the best grammar I've seen so far, but there's almost zero resources to learn it. I missed the one time #ANU ran their course on line, and picking it up by listening to the news didn't work be because it's diverged too far from #English

#introduction copied from my other profile @Kirt@lingo.lol 🔠 I'm also @kirt@mastodon.social 🦣

🧬 Side tracked #biologist

🌏 from the #WesternPacific region

#Monolingual 🏴 #English speaker, curious about more #Languages than I will ever learn 🇪🇺 #German 🇩🇪 #RussianLanguage :flag_wbw: #Hindi 🇮🇳 #Urdu 🇵🇰 #Farsi 🌙 #Arabic 🇲🇹 #Maltese 🇮🇲 #Manx 🇵🇬 #TokPisin

🔠 I can read familiar names in multiple scripts but I am only fluent in English & German is the only other language know well enough to be useful.

🤖 i click "translate" a lot

Languages evolve, this means they are alive.

🧬 Side tracked biologist

🥄 Looking for my niche

🌏 Western Pacific

#Monolingual #English speaker, curious about more #Languages than I will ever learn #German 🇪🇺 #RussianLanguage #Hindi 🇮🇳 #Urdu #Farsi #Arabic #Maltese 🇮🇲 #Manx 🇵🇬 #TokPisin

🔠 So far I can read familiar names in multiple scripts but I am only fluent in English & German is the only other language know well enough to be useful.

🤖 i click "translate" a lot

🦣 I'm also @kirt@mastodon.social

The Germanic Languages

Ekkehard Konig, Johan van der Auwera | 2013

>>> The part on Pidgin English, especially Tok Pisin is very close to an analysis of Toki Pona

The Beginning

I came to find Tok Pisin via finding Toki Pona (more about that journey here) and after looking through the language, decided I would like to at least attempt to learn it.

I have only reference materials: a Tok Pisin — English dictionary (this one) and various articles from ANU Pacling.

I intend to document my journey here, and likely will often be asking questions, writing samples (which may be incorrect). Maybe one day I will have the opportunity to travel to PNG and immerse myself in the language.

Learning a New Language (or Six)

[...]

I explored the “other languages” section and found Toki Pona, a constructed language (like Esperanto) that contained a minimal vocabulary (around 120 words). I read about it, and soon started a course (Can these things, really be called 'courses' in the sense that one would traditionally take a course at a bricks and mortal education facility?) and was on my way to learning everything.

I trawled the internet for more information on Toki Pona and how to speak it (both from a pronunciation aspect and also from a grammatical aspect) and found little recent writings. I decided I would order pu (the Official Toki Pona Book) and hoped it would answer all my questions.

It didn't.

So I Moved On

Toki Pona takes influence from Tok Pisin an official language of Papua New Guinea. And it just so happened that Memrise had a course on this. So off I went.

Through the first one, I went. Then onto a second. I have even gone as far as purchasing a printed Tok Pisin—English Dictionary and have found some interesting resources at ANU's Asia-Pacific Linguistics page.

Given much of Tok Pisin's influence is from English, I have found it relatively easy to comprehend. I think I am pronouncing things right, but I just don't know. And I like the language. It is (to me) simpler, much simpler than anything else I have looked at.

[...]

TOK PISIN AND MERI BLOUSES

EMILY INKAVIENG | Apr 20, 2015

https://emilyinkavieng.wordpress.com/2015/04/20/tok-pisin-and-meri-blouses/

Let’s… Tok Pisin!

April 28, 2016

Marco Puddu

25 augustus om 19:21

Tok Pisin:

mi wok

yu wok

em i wok

Tom i wok

Toki Pona:

mi pali

sina pali

ona li pali

jan Ton li pali

Did you notice anything?

Piotr Mittelstaedt

"i" is skipped with "I" and "you". Is it the main source of the same scheme in tp?

Zoltán Gorza

if I remember correctly, yes

Sonja Lang

Yes it is

https://www.facebook.com/groups/sitelen/permalink/1898386100215766/

#TokiPona #li #tan_nimi #nasin_tan #TokPisin #syntax #syntasi #sona #anno2018

Tok Pisin

All but one of these derive ultimately from English.

18: insa (insait, from Eng. inside), kama (kamap, Eng. come up), ken (ken, Eng. can), lili (liklik 'small'), lon (long 'at', from Eng. along), lukin (lukim, Eng. look 'em), meli (meri 'woman', from Eng. Mary), nanpa (namba, Eng. number), open (open, Eng. open), pakala (bagarap, Eng. bugger up), pi (bilong 'of', from Eng. belong), pilin (pilim, Eng. feel 'em), pini (pinis, Eng. finish), poki (bokis, Eng. box), suwi (swit, Eng. sweet), taso (tasol 'only, but', from Eng. that's all), toki (tok, Eng. talk)

Also obsolete pata (brata, from Eng. brother)

http://speedydeletion.wikia.com/wiki/Toki_Pona