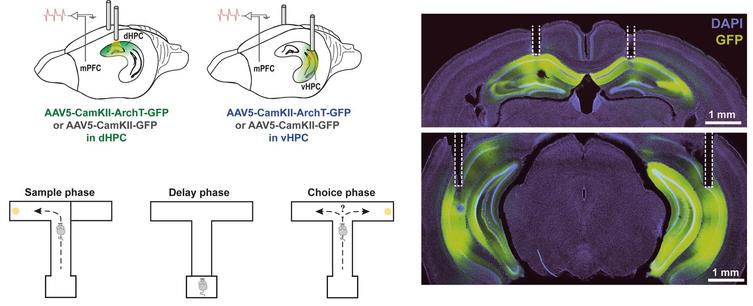

#Hippocampus & #PFC interact to support spatial #WorkingMemory, but are dHPC & vHPC functionally redundant in this? This study shows that both regions contribute differentially to spatial WM & coding of spatial info by PFC @PLOSBiology https://plos.io/4cXyddO

#WorkingMemory

Mastering Mindfulness: Train Your Brain for Better Focus!

#Mindfulness #AttentionControl #BrainTraining #Focus #MentalHealth #CognitiveScience #MindfulLiving #Neuroscience #WorkingMemory #SelfImprovement #AttentionDeficit #MindfulnessPractice #MentalClarity #BrainHacks

Childhood neglect linked to slower working memory development, study finds https://www.psypost.org/childhood-neglect-linked-to-slower-working-memory-development-study-finds/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=mastodon #ChildhoodNeglect #CognitiveDevelopment #WorkingMemory #ExecutiveFunction #PsychologyResearch

Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences

Scott Douglas Jacobsen

In-Sight Publishing, Fort Langley, British Columbia, Canada

Correspondence: Scott Douglas Jacobsen (Email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com)

Received: January 22, 2025

Accepted: N/A

Published: February 1, 2025

Abstract

This interview presents a series of vivid, first-hand accounts by Paul Cooijmans, a longtime test creator and administrator in high-I.Q. circles, as recounted in conversation with Scott Douglas Jacobsen. Cooijmans details a variety of bizarre, humorous, and at times tragic anecdotes spanning several decades. Topics include inexplicable complaints about test language and delivery, elaborate instances of test fraud—including the case of a beheaded man and pseudonymous retesting—the misadventures of high-I.Q. society members (from a casino robber to a documentary subject whose life ended in tragedy), and curious occurrences involving death threats, spurious professorate offers, and wildly unorthodox interpretations of test instructions. These stories highlight not only the challenges of maintaining test integrity and clear communication in a multicultural, digital environment but also the human eccentricities that arise when intelligence testing intersects with personality, ambition, and occasional mischief. The interview ultimately underscores the unpredictable and often surreal landscape of high-I.Q. society interactions.

Keywords: Cognitive Abilities, Cognitive Assessment, Cognitive Profiles, Diagnostic Context, Digital IQ Testing, Educational Diagnostics, Educational Interventions, Fluid Reasoning, Fraud in Testing, High-IQ Societies, Intelligence Anomalies, Intelligence Fraud, IQ Communication, IQ Controversies, IQ Discrepancies, IQ Distribution, IQ Fetishization, IQ Measurement, IQ Test Administration, IQ Test Security, IQ Tests, Multiple Intelligences, Online IQ Testing, Percentiles, Psychometric Evaluation, Psychometrics, Sensorimotor Abilities, Standard Deviation, Test Timing, Unconventional IQ Cases, Working Memory

Introduction

The realm of high-I.Q. testing and society membership has long been fertile ground for both intellectual rigor and eccentric behavior. In this in-depth interview, Paul Cooijmans—a veteran test designer and administrator—shares an array of unusual experiences accumulated over years of administering tests, handling orders, and interacting with a diverse community of high-I.Q. individuals. From a customer who inexplicably complained about receiving an English test in lieu of a supposed “Netherlandic” version, to intricate fraud cases involving false identities and even a tragic tale of a beheaded test-taker, Cooijmans leaves no stone unturned.

The conversation also delves into episodes that range from the comically absurd—such as pseudonymous submissions by a so-called “South-African” who was later revealed to be a retest under a child’s name—to the more serious implications of test misconduct, including death threats, elaborate attempts to manipulate test results, and the challenges of verifying scores in an era of instant communication. Anecdotes about high-I.Q. society members, including a rogue member involved in a casino heist, a spamming correspondent inundating Cooijmans with daily messages, and an overly ambitious “professorate” offer from a New Zealand student, further illuminate the unpredictable nature of this specialized community.

By presenting these narratives, the interview not only provides insight into the practical difficulties of administering and safeguarding intelligence tests but also paints a broader picture of the cultural and interpersonal dynamics that animate the world of high-I.Q. societies. This introduction sets the stage for a detailed exploration of both the humorous and cautionary dimensions of test administration, while inviting readers to reflect on the interplay between standardized measurement and the uniquely human quirks that often defy neat categorization.

Main Text (Interview)

Interviewer: Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Interviewee: Paul Cooijmans

Section 1: Test Orders, Language, and Delivery Complaints

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: What happened with the people who complained about the tests being in Netherlandic, or not arriving on time?

Paul Cooijmans: On one occasion, someone ordered an English test, and upon receiving it complained that he did not know Netherlandic. This was bizarre as there was no Netherlandic whatsoever in the test. Some time later, he explicitly ordered a Netherlandic test. Again, upon receipt he complained that I had sent a Netherlandic test! Good-natured as I am, I sent him the English version for free, so that he now had two tests for the price of one.

Again later, this person ordered another test, and I sent it less than two hours after he had ordered it. To my astonishment, I then saw a public Facebook message from him in a group to which we both belonged; in it he was moaning that he had ordered one of my tests and I had not sent anything and was letting him wait for days and days. I studied the time stamps of the Facebook message and test order, and there were only minutes separating them. He must have written the whining Facebook message at the same time he ordered the test! But of course, minutes may seem days, depending on what one smokes.

Section 2: The Beheaded Man and the Fraudulent Retest

Jacobsen: What is the full story of the beheaded man, who took a test under a false name and would have won under his real name, regardless?

Cooijmans: In the early days of the Test For Genius, 1995, a Netherlander obtained a rather high score. Inexperienced as I was, I showed him the answers to the hardest problems, with explanations. To encourage people to take the test, I awarded 2000 guilders to the highest scorer before the year 2000. For some years, only few submissions came in, mostly not high. Then in 1999, a very high score was finally achieved by a South-African who appeared to be a colleague of the high-scoring Netherlander, working there as an intern. This was around the time of the total eclipse of the sun, visible in England and France for instance. The high-scoring Netherlander had told me he was planning to travel to the area where the full eclipse was visible, and that he expected this to become a life-changing event. Come to think of it, I never heard from him again after the eclipse.

So the 1999-2000 year change arrived, and the South-African was the winner. I contacted him and suggested he come collect the prize, but he declined and asked me to transfer it to his bank account, which I promptly did. He wrote me that he was returning to South Africa and, as a parting gift, sent me some answers to a test by another Netherlander who had also awarded a monetary prize to the highest scorer, albeit a much smaller prize than mine (300 guilders, if I remember well). He suggested I use them to win the prize, which I of course did not.

Some time went by, until finally in 2001 the high-scoring Netherlander had an article published in the Netherlandic journal of a large I.Q. society. It was about the spirograph, a toy with which one can draw figures of intertwined circles with wheels that rotate inside each other. He likened this to the guilloche engine, and spoke of guilloche engines he had seen in a museum. For some length he went on about rotating wheels and guilloche engines. While reading his interesting piece, the telephone rang, and a member of this society informed me that the author of the article had been found near a railway tunnel, his head cleanly separated from his trunk by the wheels of a train. It was one of the finest examples I had ever seen of what one could call a macabre sense of humour.

Since this was a mysterious event, I wrote the South-African about the tragic death, asking whether he had any idea why the Netherlander could have done such a thing. To my surprise, the next day I received a telephone call from the high-scoring Netherlander’s sister, who confessed that the South-African colleague did not exist, and his name was that of her little son. The letter had arrived at her address. She told me that her brother had used her son’s name to retest on my and other tests. Indeed, the “South-African” had informed me of his scores on Ronald K. Hoeflin’s tests, which had been taken before by the Netherlander under his own name, then under his sister’s name (he told me that at the time) and finally under the child’s name as it now turned out.

I understood why the “South-African” score on the Test For Genius had been so high; after all, I had given the answers to the hardest questions (the “Short” version of the test) to the Netherlander some years before. In fact I had had a very mild suspicion right away when receiving that test submission, which was written on the same paper as used by the Netherlander, in a vaguely similar style and handwriting. Out of piety I decided to let the Netherlander be the official winner of the Prize rather than the non-existent South-African; after all, he had the highest score after removing the fraudulent South-African one. He would have won without the pseudonymous retest, albeit that he had not registered for the Prize under his own name, which was a requirement. Around that time I also learnt of certain family circumstances that may have led to the suicide, but I believe it is not appropriate to relate those here. I did use this case when writing my novel “Field of eternal integrity”, as well as in the “Test of the Beheaded Man”. One could say that in selling those items, I am repaying myself the 2000 guilders he conned me for.

Section 3: The Casino Robber and “High Queue” Verbal Tests

Jacobsen: What happened with the high-I.Q. society member who ended up robbing a casino?

Cooijmans: This was a young man whom I had seen several times at meetings. Suddenly, an article by him appeared in the journal of a society to which we belonged, explaining he had tried to solve his financial problems by robbing a casino with a (not loaded) hand gun. Shortly after exiting the casino, he was caught by the police, I think it was actually a routine control. I corresponded with him while he was in prison and sent him a test to take by way of extra punishment, which he completed. Even from prison, he kept organizing a large yearly summer feast, which he had been doing for years already. I believe his sentence was something like a year and a half. After his release he came to live in a town close to me, and died some years later of an illness.

Jacobsen: Who is “High Queue”? What were those verbal tests they sent?

Cooijmans: A decade or so ago, the pseudonym High Queue was used by someone who spread a number of verbal analogies tests among I.Q. society members. The analogies dealt with more or less known figures in the societies in a fun-poking way, and some people were offended. It has never been officially revealed who High Queue was, but I am as good as certain it was two people. Originally only one, then another joined in and took over who was even more vitriolic. I know the names, but think it is better not to reveal them here. In private correspondence I have no objection to sharing them.

Section 4: The Documentary Subject and the Finnish Test Fraud Call

Jacobsen: What happened with the member who had a prize-winning documentary made about him and then later committed suicide?

Cooijmans: In the year 2000 I was in contact with this person, mainly about Asperger syndrome and related topics. This was both correspondence and telephone. He told me a lot about his suffering from extreme compulsions, depression, experience with being bullied, adaptations he was making to his apartment, self-administered forms of shock therapy he used to be temporarily rid of his otherwise untreatable state of compulsiveness and depression, and more. This was an extremely verbally inclined person who spoke fluently and rapidly, using a rich and high-brow vocabulary. He suffered extremely and assured me that his phenotype should under no circumstance be repeated.

Twelve years later a documentary about him, “De regels van Matthijs”, was in the news for winning a prize in a film festival in Nyon, Switzerland. It showed the bizarre adaptations he had been making in his apartment, like a hole in the wall to be able to use the space between walls for storage, a vessel to retain the water of the shower while it was warm to keep the energy in, changes to the gas tubes, and so on. You saw him soldering or welding on those tubes, and showing medications he had hoarded for his self-administered treatments. The house owner was threatening to put him out of his apartment because of all the modifications. At the end of the documentary he died. It is not clear to me exactly what the cause was, whether it was suicide or a shock therapy gone wrong. The things he did were potentially deadly so I am not giving details, but the documentary does.

Jacobsen: What happened with the Fin who called you and asked to halt the “bloodhounds” going after him for test fraud?

Cooijmans: Some twenty-five years ago the telephone rang – in those days a lot was done via telephone calls – and a Glia Society member from Finland was on the line. He confessed he had cheated when taking a few tests, both a Hoeflin test and the Cattell Culture Fair, both of which had seen a lot of fraud already in the 1990s. Some people had found this out and were harassing him about it, and he believed I was behind that and desperately begged me to make them stop. “Call back the bloodhounds” were words he used. Sadly, I knew nothing of what was going on and had no means to end the merciless, cruel persecution of this poor soul. His haunted, breaking voice still disturbs my dreams after heavy meals. He was never heard of again thereafter.

Section 5: Conspiracy Theories, a Low-Scoring Cheater, and the Time Lords

Jacobsen: What did the person lecture about regarding conspiracy theories, UFOs, and the JFK assassination at the high-I.Q. society meeting?

Cooijmans: In the mid-1990s, a large I.Q. society organized a lecture by “John Hercules”, whose real name was John Kühles; I see he has still been active in recent years. The lecture was about topics like crop circles, UFOs, and various conspiracy theories. The most remarkable thing I remember was a video of a film of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, on which you could make out that the driver of the car put his left hand over his right shoulder, holding something that looked like a gun. A shot was apparently fired, and Kennedy’s head went back. John Hercules explained that secret agents are taught to shoot with one hand over the shoulder thus. This was the only time I have ever seen that video; I never even heard about it again after the lecture. It looked authentic to me though. If it was a forgery, I do not know how it could have been made.

Section 6: Cheating Confessions and Persistent Commercial Spam

Jacobsen: How did the low-scoring test cheater pose as a test designer?

Cooijmans: In 2006, this person scored zero on a test and disputed the result, claiming I had not reported the true raw score. Shortly thereafter another person took the same test and also scored zero. Right after I had reported the score to the second person, the first person responded angrily, saying, “You did not score that test honestly, I changed six answers so my score can not be zero again”. Clearly he had let a friend of his send the retest.

Later in a Facebook group for test creators, I observed him spreading a test of his own hand. Or rather, someone else spread it for him as he was not on Facebook himself, it seemed.

Jacobsen: What was the phone call about the Time Lords in the future Giga Society? Who were these “White Masters” mentioned?

Cooijmans: In the 1990s I wrote a series of fictional stories in Netherlandic about the Time Lords, who were Giga Society members communicating with me from the future. After publication of one episode in a Netherlandic I.Q. society journal, a lady called me to ask if the Time Lords were the same as the White Masters she was in regular contact with. I think she referred to the White Masters of Anthroposophy. I kindly answered that I did not know if it concerned the same entities, and that I would ask them on the earliest convenient occasion. Somehow I have not got to that yet.

Jacobsen: What’s the story behind the person who confessed to cheating and then begged remaining hidden?

Cooijmans: In the mid-1990s a Netherlandic I.Q. society member told me he had cheated by using dictionaries when taking the W-87, the admission test of the International Society for Philosophical Enquiry at the time. Since this test was vocabulary-based, in English, and disallowed dictionaries despite being unsupervised, this resulted in a score much higher than his real intelligence level. He also said that he would one day raise this matter in the I.S.P.E. and confess the fraud. It is unknown whether he ever did that.

Later in one of my satirical articles in the Netherlandic journal of this society (not the I.S.P.E. but the other one), I announced that the time of unmasking was nigh for test frauds. On the day of publication, he called me, almost panicking, begging me not to betray him, and claiming that what he had done was not fraud, even offering to help me take that test and get me into the I.S.P.E. that way. That is so revealing of the ethical level of such a person, that it can even occur to him that I would participate in such fraud.

Jacobsen: Who was spamming you persistently with commercial messages? How did you handle it?

Cooijmans: It is better not to name names, although in this case my hands are itching; this person sent me a friend request on Facebook and, after I accepted, at once commenced sending me commercial messages asking me to invest money in his projects. Every time I unsubscribed, he added me again. After a few such rounds I unfriended him. Some time later I saw him writing under a Facebook post about me that HE had unfriended ME because I had “annoyed” him… Such behaviour I find beneath contempt.

Section 7: A Cry for Help and a Request for Controlled Contact

Jacobsen: What is the story of the individual who sent a strange “help” message and then assaulted a pregnant woman?

Cooijmans: In the early 2020s I received an empty electronic mail message with an attachment that was a photo of a piece of paper with, barely legible, “help” scribbled on it. I ignored it for the time being. A few years or so later, I came across the message again in my absurdly large e-mail archive, and decided to look this person up on the Internet to see if nothing bad had happened. Just to reassure myself, so to speak. After all, one never knows. And so I learnt to my amazement that the person – referred to as a “woman” in some sources but looking like a male – had been arrested for assaulting a breastfeeding woman in her car (I mistakenly said “pregnant” before), seemingly trying to steal the baby. Video footage of the arrest can be found online.

So I suppose the lesson is, never ignore a cry for help! My bad, as one says idiomatically.

Jacobsen: What was with the request from the person who wanted you to test everyone seeking her contact information?

Cooijmans: This person felt overwhelmed with people wanting to contact her, and decided to go offline and in hiding for an undetermined period. On her request, we arranged this so that her web location would refer people to me, and I would administer a certain test to them, and only if they exceeded a particular very high score would I bring them in touch with her. She warned me that it would get busy with contenders.

No one ever showed up.

Section 8: Unconfirmed Test Scores and Shifting Identities

Jacobsen: What’s the background on two unconfirmed Logima Strictica 36 scores of 32?

Cooijmans: One day, someone showed me his Logima Strictica 36 score report, and it reported 32 right. The report was fully authentic, as far as I could tell. Still, he told me that the test scorer and author, Robert Lato, had denied the score afterwards and sent him a new report with a much lower score, stating that the first report had been a “joke”. The published statistics also never contained the score of 32. As an interjection, I remind the readers here that the “official” statistics and norms of L.S. 36 as found online are, in my perception, a clandestine rogue project by an individual who was not satisfied with his I.Q. on the test according to the official norms at the time, and made his own norms, giving himself a very much higher I.Q., and then aggressively pushing his norms as if they were the official ones.

Years later, a second candidate told me that he, too, had received a Logima Strictica 36 report with a raw score of 32. This score is missing from the published statistics as well.

Jacobsen: Why did somebody contact you under different names over the years?

Cooijmans: In the early 2000s when I had just acquired a computer and Internet connection, someone corresponded with me briefly and mentioned various personal circumstances, such as being sixteen years old, pregnant, and considering travelling to another country. Over the fifteen years or so that followed, this person resumed contact with me a few times after years-long interruptions, but under different names. I knew it was the same person because she referred to the circumstances mentioned during the initial period of correspondence, showed photos of the child growing up and so on, but for some reason she never wanted to confirm the name she used then, and which I remember well.

Section 9: Outlandish Academic Offers, Delusions, and Speed Dating

Jacobsen: What happened with the supposed “professorate” offer at a New Zealand university? The offer from someone who turned out to be a student.

Cooijmans: This person told me that his university would like to have me as a professor or something like that; I only needed to say “yes” and I was in. This struck me as rather strange, if only because I lived literally on the other side of the world so how could I ever get to my workplace in time each morning if I took on that job? It would take hours to get there! I did not get clear responses to my questions as to precisely how he had in mind I could work in New Zealand, and then seamlessly his text morphed into suggesting that I come study for a PhD there.

I pointed out I did not even have a Master’s degree, so was not eligible for such a course, but he assured me that prior degrees were entirely unneeded: “You just read the books, take the exams, and you have a doctorate!” I was quite certain that doctorates are not conferred thus, but rather through doing research and writing a dissertation or series of articles; but then, this was not the first time that someone from Oceania presented me with this alternative PhD journey. Meanwhile it had become clear that this was just a student with a lot of imagination. In the dialect of the region where I live, such a person might be called a “lulleman”. A bit later, after the advent of YouTube, he began sending me messages containing only hyper references to videos with the remark, “This video is awesome!” I did not know the word “awesome” at the time, and, seeing the videos he sent me, assumed it meant the same as “awful”.

Again later when Facebook came up, I saw him writing unintelligent non-committal high-on-the-horse comments under messages of I.Q. society members; never have I seen him put out even one sentence that made sense.

Jacobsen: What was the deal with the person who experienced bizarre delusions of reference?

Cooijmans: This was in the early 2000s. By that time I had an Internet connection and electronic mail account, and this person, an I.Q. society member and author of a Netherlandic book on giftedness, corresponded with me for a while after I had provided information she needed for the book. She told me she always studied certain one-lined cartoons in a particular newspaper with great attention, as they tended to be about her. The cartoonist had hacked her computer, she said, and was using her personal life history as a basis for his daily strip “Sigmund”.

But it got worse; she also claimed that the television series “Fantasy Island” – Ze plane! Ze plane! – was based on short stories written by her and stolen from her hacked computer. The catch is that this series was made in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so twenty years earlier, when she most likely was not writing on a computer yet. When I carefully pointed this out to her, she insisted, “But I am certain! I can see with my own eyes that every episode follows my story line to the smallest detail!” Just in case she reads this interview: No, this is not about you.

Jacobsen: How was the “speed dating” event of the high-I.Q. society?

Cooijmans: It was held in the open air in 2010, somewhere in the middle of the Netherlands. The females were seated in a very wide circle, dozens of metres removed from one another. The males went round, spending five minutes or so with each female. You got a form on which to indicate if you were interested in each given candidate, and afterwards the organizers compared these forms to determine the “matches”. Every participant received a list of one’s matches to take home. I think I had about four.

In the days thereafter I was briefly in electronic mail contact with each of the “matches”. While nothing came out of it, one case was particularly dismissive; when I reminded her of topics we had discussed at the “speed date”, she downright denied them and said I must be mistaking her for someone else. I considered that thoroughly, mentally went through all the conversations I had had that day, but no, I was not mistaken. I suppose this is some people’s way of saying, “I do not want further contact”.

Section 10: COLT Misfires, Web Host Mayhem, Death Threats, and Final Oddities

Jacobsen: What is the case of the COLT misfiring? What were the consequences?

Cooijmans: In 2009 someone ordered the “Cooijmans On-Line Test – Two-barrelled version” and I sent him the login information. He protested that this was not the two-barrelled version, but the earlier one, for which he claimed to have already paid twice, the second time after losing his password.

I looked through my meticulously kept financial books and test database, and saw he had never ordered the earlier COLT version (but had ordered other tests), and had never had login information before. I explained to him that the COLT was originally freely available online for everyone, without logging in, and that the login system was introduced later on. And that he might have been on the COLT before the login system came, and later noticed he could not log in and wrongly thought he had lost his password. And that I would not let someone pay a second time after losing the password. And that this was definitely the two-barrelled version, and that the second barrel would appear as he advanced.

But he stubbornly maintained this was not the two-barrelled version, and that he had a login account earlier and had paid twice before for the same test. “You are an idiot and I resent you”, he uttered after my kind explanation above. I deleted his account and refunded the fee. It is especially bizarre that someone can deny that a test is a certain test while I, as the creator, am the one who knows what test it is.

Jacobsen: What happened when your web host took down your site?

Cooijmans: This was someone who had been in contact with me about “Space, Time, and Hyperspace”, a subtest of the Test For Genius. He claimed the test was invalid, and wanted some kind of credit for having proven that. I invited him to send answers, but he refused, apparently he first wanted some guarantee that he would receive a perfect score for showing that the items were invalid (which he had not shown or explained at all at that point, he only stated that they were invalid but without arguments or explanations). There was a stubbornness and rigidity in his behaviour that is often associated with psychotic disorders, and later he indeed told me he was schizophrenic.

Since I was not willing to give him any credit or guarantee for simply stating the test was invalid, he went berserk and put the test with his alleged proof of invalidity online. But very soon thereafter he removed it again, regretting it. He also made a number of web sites with domain names that referred to me or my tests, and that attempted to install malicious software on the visitor’s electronic computer upon loading the page.

A bit later he offered to host my web site for free. Forgiving as I am, I let him do that. For a while it worked, then suddenly my web site was gone and I never heard from him again.

Jacobsen: What led to the death threat? How did you respond?

Cooijmans: To start at the likely beginning, in 2001 someone from Germany ordered the German version of the Test For Genius, which I sent him. A few months later he began to complain that what I had sent was not the German Test For Genius. Again, that was bizarre, given that I, as the creator of the test, am the one who knows which test it is. Perhaps he had expected it to be more similar to the English version, but of course one can not translate test problems literally, one has to find some adaptation that works in the other language. He maintained stubbornly and rigidly that this was not the German Test For Genius, and eventually I offered to refund the two dollars he had paid me (that was the test fee in those days). Suddenly he withdrew and refused to give his address, making it impossible for me to send the money back. I heard nothing from him for a long time.

Then in 2003, 51 minutes before my birthday, I received this friendly message from Germany by electronic mail. Although I have never been able to verify it with certainty, I suspect it came from the person in the previous paragraph:

Hello Paul,

How are you doing, old friend?

Well, I hope! For the moment.

I’ll be coming to Helmond next month.

And I’ll get rid of you.

I will take my time.

I know where you live.

I know where you go.

Do you remember me?

We met 2 years ago.

You stupid little prick.

Prepare to suffer.

Prepare to die.

See you soon,

mmmfred 196

A last test for you:

One of these people will die soon. Select this person:

- Herold T – b. Peter Q – c. Arnold B – d. Paul C – e. Jon N

—

+++ GMX – Mail, Messaging & more http://www.gmx.net +++

Bitte lächeln! Fotogalerie online mit GMX ohne eigene Homepage!

I always find the “Bitte lächeln!” rather funny in this context. I reported this to the provider, gmx.net, and they replied, apologizing for the “virus” I had received! But it is not exactly a virus. I have kept this message on my web location, paulcooijmans.com , in the category “Ethics”, with some more information.

Section 11: Sylvester Stallone and the Post-Modernist

Jacobsen: Who tried to emulate Sylvester Stallone? What was the end result?

Cooijmans: In the late 1990s, a former class mate of mine got back in contact. For a while he took guitar lessons from me, and had the habit of not wanting to leave when the lesson had ended, or at least not until my refrigerator was empty. On one occasion, he managed to eat an entire box of hagelslag (chocolate sprinkles) with the one slice of bread I had left to offer him. I made use of his presence by administering the Giga Test to him, an individual supervised test I had at the time. Remarkably, he had a perfect score on the mental arithmetic section.

He also told me that, after leaving school, he had developed a fixation on Sylvester Stallone, as in the Rocky films. He had trained for years to obtain a similar physique, and this included the use of anabolic testosteroids. He said he had beaten lamp posts in the streets with his fists until the bones in his hands broke, and had been hanging around in the nightlife, looking for people he could challenge to a fight. He had become a lot more aggressive and dominant than in our school days, and once when I tried to get him out of my house he refused and threatened to hit me.

At one point he became schizophrenic and ended up being hospitalized for long periods, sometimes under force for assaulting a psychiatric nurse. Once he escaped and walked all the way to my house late at night. When I opened the door, he said he wanted beer. I did not let him in, and he walked back again. He also had a habit of calling me on the telephone frequently, sometimes in the middle of the night so that I had to get out of bed and down the stairs, and then he said two words and hung up again. Once I changed my telephone number for that reason, but he found out the new number by calling my mother, whose number he still had from when we were class mates and I lived with my parents. He had become vengeful toward Stallone, and wanted to travel to the United States one day to give Sly a good beating.

He also spoke of a girl from our class, and said he had always been secretly in love with her. As it happened, she worked at the hospital where he was kept, and sometimes he waited for her to come out when her shift ended, which she did not like. He knew where she lived, and had stood guard opposite the house to observe her and her husband, whom he was planning to murder he said; it never got to that, insofar as I know. On one occasion he confided that even in our school days, he had been fantasizing during class about the girls in our school; the details of his fantasies are not suitable for publication, but involve knives and female private parts.

Since he was not making progress on the guitar and never practised, I ended the lessons and refunded the remainder of the fee, which he had paid in advance. The last time I saw him was when I participated in a running race on the terrain of the psychiatric institute where he lived. He kept intrusively talking to me while I tried to register for the race, aggressively hushing up the lady of the race administration who tried to enter me.

Jacobsen: What was noteworthy about the post-modernist who attended a meeting in the 1990s?

Cooijmans: This was a university teacher – I do not know in which field, perhaps post-modernism? – who regularly attended a certain I.Q. society meeting where I was present a number of times; the same place that was frequented by the casino-robber. I remember he expressed amazement that we were not all as thrilled as he was about post-modernism (I had no idea what that was at the time). Occasionally, he jumped up mid-sentence, spread out his arms, and ejaculated, “I’m here, I’m queer, check me out!” whereupon a certain girl applauded enthusiastically, saying, “Hey, totally okay man!” while the rest continued their conversation as if nothing had occurred.

Section 12: Conclusion

Jacobsen: Why did the interviewer change the conditions of the interview after already agreeing?

Cooijmans: Years ago someone wanted to interview me, and I said I was willing to cooperate, provided my answers would be used verbatim. He agreed, so I told him we could go ahead as far as I was concerned. Then he suddenly changed the conditions, saying that if I answered something he did not like or that made him look stupid, he would want me to change the answer. Of course I could not agree to that, and called off the interview. In fact I broke off contact with him for some time, as I find such behaviour despicable. My understanding is that this person had a fear that his questions were rather stupid, and was afraid that my answers would reveal that to the world; and he may have been right.

Jacobsen: Who has been spamming you for nearly two decades, even ten or more messages a day?

Cooijmans: Of course I can not name names in such cases, but one person has been sending an almost continuous stream of nonsensical messages, sometimes ten to twenty per day, since about 2005. I do not respond to most of them; occasionally I have to respond when he orders or takes tests. The messages make frequent mention of topics like the Central Intelligence Agency, China, some of the Giga Society members, hedge funds, hot girls, the Caribbean, and more.

Now and then the person also sends sensitive personal information, such as his street address, a photo of his identity card, login information of his e-mail account, medical information such as that he has schizophrenia, and so on.

Jacobsen: Thank you for the opportunity and your time, Paul.

Cooijmans: I never know what to say here. On second thought, I remember another weird occurrence; someone applied for membership in a society run by me, and I referred the person to the relevant society’s web location for the qualification information and registration form. Somehow this did not agree with the person, and she began to ask me which society I meant and what the pass level was. This was backward because she was the one who was applying. After some writing up and down it turned out she had no idea to which society she was writing and what the entrance requirement was. Again more writing up and down revealed she had been doing a mass application to many societies at once, so when I responded, she had no clue who I was and what societies I was involved in.

I subtly educated her to the extent that this was not how one applies for membership in I.Q. societies, and that one should study the information on a particular society’s web location before applying to that society. Indignant, she began to lecture me about kindness and compassion, and I ceased responding.

Finally, in the early days of the Test For Genius again, a Netherlander who had ordered the test called me. He said he had a perfect score on the Cattell Culture Fair, so 50 right on both forms and “I.Q.” 183. In his communication and further behaviour, he was a complete scatterbrain uttering mainly fast-flowing incoherent rambling. Since my test was typed on a typewriter (Olivetti) with hand-drawn pictures, he offered to computerize it for me. Out of curiosity, I let him send me his version.

I had rarely been so horrified. He had mangled literally everything: The instructions had been rewritten in a style I would consider patronizing toward primary school children, let alone intelligent adults. The verbal problems had been “corrected” in ways that betrayed he had not only not understood the problems, but had even not grasped the difference between the verbal analogies and the association problems. The spatial problems were simply missing as he possessed no computer graphics skills; he had left room for me to draw them in by hand, and even that room was immensely too small for the problems to fit there. I kindly thanked him for his efforts and reused the back of his printouts as scrap paper.

Discussion

The conversation with Paul Cooijmans offers a rare, firsthand glimpse into the unpredictable and often surreal world of high-I.Q. test administration and society membership. A recurring theme throughout the dialogue is the juxtaposition of rigorous testing procedures against a backdrop of personal eccentricities and unexpected human behavior. Several notable observations emerge:

Cooijmans recounts several instances where test recipients either misunderstood or manipulated the intended purpose of the tests. For example, the same customer who initially complained about receiving an English test despite ordering it, later insisted on a Netherlandic version—even though the test content remained unchanged. These incidents underscore the challenges that arise when language expectations, test administration, and individual perceptions intersect in a digital age where timing and communication can be easily misinterpreted.

One of the most dramatic episodes involves a candidate who submitted a fraudulent retest under multiple names—a maneuver that led to the infamous “beheaded man” case. This incident not only highlights vulnerabilities in test security but also reflects the lengths to which some individuals will go to manipulate outcomes. The fact that a high-scoring Netherlander eventually used pseudonyms (including that of a minor) to retake tests introduces ethical dilemmas that persist in high-stakes testing environments.

The narrative is replete with stories of individuals ranging from a would-be casino robber to a persistent spammer, and even to a person whose bizarre delusions of reference blurred the lines between personal identity and creative expression. These accounts suggest that within high-I.Q. circles, a combination of high cognitive ability and idiosyncratic personality traits can lead to both innovative contributions and, at times, destructive behaviors. The diversity of these experiences demonstrates that high intelligence does not uniformly translate to socially conventional behavior.

The interview highlights how digital platforms—such as Facebook and email—serve as double-edged swords. While they facilitate immediate feedback and rapid test delivery, they also enable misinterpretations (e.g., the exaggerated wait times) and provide avenues for both overt and covert manipulation of test results. The discussion of spamming and the misrepresentation of test conditions further illustrate the complexities inherent in administering tests in an era where online communication dominates.

The anecdotes raise important questions regarding ethical responsibilities and logistical challenges in test administration. Issues such as the proper handling of test fraud, maintaining secure communication channels, and ensuring that test takers have a clear understanding of what is expected of them are recurring concerns. The balance between being a benevolent test creator and maintaining strict quality control is shown to be delicate—often with humorous, yet cautionary, consequences.

In sum, the discussion elucidates the unpredictable interplay between standardized testing and human behavior. It emphasizes the need for clear protocols, robust security measures, and an understanding of the diverse motivations and behaviors of test-takers. While the high-I.Q. community is marked by intellectual brilliance, it is also subject to human foibles that can complicate even the most carefully designed assessments.

Methods

The interview with Paul Cooijmans was conducted in a semi-structured format on a date prior to its publication on January 22, 2025. Questions were designed to elicit detailed responses about oddities of experience of Cooijmans over many years in this area. Thematic question were sent based on prompts to Cooijmans who then provided typed responses.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current article. All interview content remains the intellectual property of the interviewer and interviewee.

References

(No external academic sources were cited for this interview.)

Journal & Article Details

- Publisher: In-Sight Publishing

- Publisher Founding: March 1, 2014

- Web Domain: http://www.in-sightpublishing.com

- Location: Fort Langley, Township of Langley, British Columbia, Canada

- Journal: In-Sight: Interviews

- Journal Founding: August 2, 2012

- Frequency: Four Times Per Year

- Review Status: Non-Peer-Reviewed

- Access: Electronic/Digital & Open Access

- Fees: None (Free)

- Volume Numbering: 13

- Issue Numbering: 2

- Section: A

- Theme Type: High-Range Test Construction

- Theme Premise: “Outliers and Outsiders”

- Theme Part: 33

- Formal Sub-Theme: None

- Individual Publication Date: February 1, 2025

- Issue Publication Date: April 1, 2025

- Author(s): Scott Douglas Jacobsen

- Word Count: 6,197

- Image Credits: Paul Cooijmans

- ISSN (International Standard Serial Number): 2369-6885

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Paul Cooijmans for his time and willingness to participate in this interview.

Author Contributions

S.D.J. conceived and conducted the interview, transcribed and edited the conversation, and prepared the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

License & Copyright

In-Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

© Scott Douglas Jacobsen and In-Sight Publishing 2012–Present.

Unauthorized use or duplication of material without express permission from Scott Douglas Jacobsen is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links must use full credit to Scott Douglas Jacobsen and In-Sight Publishing with direction to the original content.

Supplementary Information

Below are various citation formats for Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences.

- American Medical Association (AMA 11th Edition)

Jacobsen S. Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences. February 2025;13(2). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird - American Psychological Association (APA 7th Edition)

Jacobsen, S. (2025, February 1). Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences. In-Sight Publishing. 13(2). - Brazilian National Standards (ABNT)

JACOBSEN, S. Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences. In-Sight: Interviews, Fort Langley, v. 13, n. 2, 2025. - Chicago/Turabian, Author-Date (17th Edition)

Jacobsen, Scott. 2025. “Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences.” In-Sight: Interviews 13 (2). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird. - Chicago/Turabian, Notes & Bibliography (17th Edition)

Jacobsen, S. “Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences.” In-Sight: Interviews 13, no. 2 (February 2025). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird. - Harvard

Jacobsen, S. (2025) ‘Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences’, In-Sight: Interviews, 13(2). http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird. - Harvard (Australian)

Jacobsen, S 2025, ‘Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences’, In-Sight: Interviews, vol. 13, no. 2, http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird. - Modern Language Association (MLA, 9th Edition)

Jacobsen, Scott. “Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences.” In-Sight: Interviews, vol. 13, no. 2, 2025, http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird. - Vancouver/ICMJE

Jacobsen S. Conversation with Paul Cooijmans on Strange Correspondence and Weird Experiences [Internet]. 2025 Feb;13(2). Available from: http://www.in-sightpublishing.com/cooijmans-strange-weird

Note on Formatting

This layout follows an adapted Nature research-article structure, tailored for an interview format. Instead of Methods, Results, and Discussion, we present Interview transcripts and a concluding Discussion. This design helps maintain scholarly rigor while accommodating narrative content.

#cognitiveAbilities #CognitiveAssessment #CognitiveProfiles #DiagnosticContext #DigitalIQTesting #EducationalDiagnostics #EducationalInterventions #FluidReasoning #FraudInTesting #highIQSocieties #IntelligenceAnomalies #IntelligenceFraud #IQCommunication #IQControversies #IQDiscrepancies #IQDistribution #IQFetishization #IQMeasurement #IQTestAdministration #IQTestSecurity #IQTests #multipleIntelligences #OnlineIQTesting #Percentiles #PsychometricEvaluation #psychometrics #SensorimotorAbilities #standardDeviation #TestTiming #UnconventionalIQCases #WorkingMemory

On High-Range Test Construction 28: Dr. Kristóf Kovács on Accuracy in IQ, Intelligence, and Cognitive Abilities

Scott Douglas Jacobsen

In-Sight Publishing, Fort Langley, British Columbia, Canada

Correspondence: Scott Douglas Jacobsen (Email: scott.jacobsen2025@gmail.com)

Received: January 10, 2025

Accepted: N/A

Published: January 22, 2025

*Updated January 27, 2025.*

Abstract

This interview includes a detailed conversation between Scott Douglas Jacobsen and Dr. Kristóf Kovács, a Senior Research Fellow and Lecturer at the Institute of Psychology and the Department of Counselling and School Psychology. Dr. Kovács leads the Cognitive Abilities Lab, focusing on research in cognitive abilities, intelligence, psychometrics, and their measurement. He critiques the limitations of IQ tests in assessing creativity, sensorimotor skills, or interpersonal abilities, emphasizing the need for detailed profiles for diagnostics over societal “IQ fetishism.” Dr. Kovács explores the importance of ethical and transparent research practices and provides a nuanced understanding of IQ scores and their applications. The discussion includes the historical context of IQ testing, its practical applications, and the sociological implications of the g-factor as a statistical construct.

Keywords: Cognitive Abilities, Diagnostic Context, Educational Interventions, Fluid Reasoning, IQ Distribution, IQ Fetishization, IQ Measurement, IQ Tests, Multiple Intelligences, Percentiles, Psychometrics, Sensorimotor Abilities, Standard Deviation, Working Memory

Introduction

The document features an engaging interview with Dr. Kristóf Kovács, conducted in 2025 by Scott Douglas Jacobsen, as a recommendation from Björn Liljeqvist, former chair of Mensa International. Dr. Kovács, a Senior Research Fellow and Lecturer at the Institute of Psychology and the Department of Counselling and School Psychology, shares his insights on the measurement of intelligence, cognitive abilities, and psychometric tools. Leading the Cognitive Abilities Lab, Dr. Kovács critiques the limitations of IQ tests, emphasizing their inability to measure creativity, sensorimotor skills, and interpersonal abilities. He highlights the importance of providing detailed diagnostic profiles rather than relying on singular IQ scores. The interview delves into societal misconceptions, such as “IQ fetishism,” and clarifies the statistical construct of the g-factor, noting its utility in sociological studies but limited relevance for individual diagnostics. Dr. Kovács’ work underscores the need for ethical and transparent research practices and the refinement of tools to better capture the complexities of cognitive abilities. His perspectives challenge conventional views on intelligence testing and advocate for a more nuanced understanding of cognitive profiles for practical applications, ranging from education to legal contexts.

Main Text (Interview)

Interviewer: Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Interviewee: Dr. Kristóf Kovács

Section 1: Introduction and Context: Setting the Stage

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: So, today, we are here with Dr. Kristóf Kovács. This interview is a recommendation from Björn Liljeqvist, so thank you, Björn. I interviewed with him a while ago. I have been interviewing many individuals from various groups, including Mensa. In high-IQ communities, I wanted to get a professional opinion about testing. So, I posed the first big question that people might have if they are stumbling upon this interview: How much do IQ tests measure intelligence? What is the overlap between IQ and intelligence? In other words, what is the overlap in this Venn diagram?

Section 2: Defining Intelligence: Beyond the Traditional Views

Dr. Kristóf Kovács: That is a very old question. Whether IQ tests measure intelligence is a controversial issue. I do not think it is a particularly useful question because, to a large extent, it depends on how we define intelligence. If intelligence traditionally meant some form of cognitive ability, then today, with enough research, one can find references to all sorts of intelligence.

There is a paradox I perceive here. People who are very critical of IQ tests and the concept of intelligence argue that IQ testing is flawed. Yet, simultaneously, they are quick to embrace the term intelligence. There is always an alternative concept proposed to counter IQ. The first major alternative was emotional intelligence, which, after 20–25 years of research, became a meaningful scientific construct, in my opinion. However, it does not necessarily need to be called intelligence—it could be termed emotional ability. Nevertheless, now we see references to concepts like spiritual intelligence, naturalist intelligence, and other types of intelligence.

Of course, IQ tests clearly do not measure intelligence if intelligence is defined broadly enough to include aspects such as one’s relationship to spirituality. IQ tests do not assess spirituality, emotionality, one’s connection to nature, interpersonal skills, self-awareness, or other qualities often labelled as intelligence today. Therefore, the extent to which IQ tests measure intelligence depends entirely on how intelligence is defined. Debates over definitions, in my experience, are not particularly useful.

I try to avoid using the term “intelligence” whenever possible. Interestingly, I used to work extensively with Mensa, which is probably how you found me through Björn. However, I am primarily a researcher specializing in individual differences in cognition. My academic work at the university involves a research position.

In my research, I cannot entirely avoid using the term “intelligence,” particularly in contexts related to Mensa, but I prefer to frame my research interests as focusing on cognitive abilities rather than intelligence. When we discuss cognitive abilities, there is no meaningful way to include aspects like spirituality.

Section 3: Cognitive Abilities vs. Intelligence: A Conceptual Shift

My research lab is called the Cognitive Abilities Lab—it is not called the Intelligence Lab. In my work, I consciously use the term cognitive abilities because it is plural. Intelligence, by contrast, is singular. As a researcher, discussing a range of specific abilities, such as fluid reasoning or crystallized knowledge, is far more meaningful.

Working memory or perceptual speed, and so on, are more meaningful constructs than a single general intelligence. General intelligence, in my opinion, is an index derived from various specific cognitive abilities. Still, it is not an ability in itself. For this reason, I prefer discussing cognitive abilities rather than intelligence. This approach avoids the type of definitional debates you raised. That said, I don’t want to circumvent the question completely.

IQ tests do a reasonable job if we define intelligence as cognitive ability. There’s a famous saying from Winston Churchill that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others humanity has tried. When I teach this or present at conferences, I often draw a parallel, saying that IQ tests are the worst instruments for measuring intelligence—apart from all the others psychology has ever tried.

Jacobsen: That’s good. A different way to frame it is from an empirical basis. If we’re examining cognitive abilities, what has emerged from research over the past century or so regarding what IQ tests measure? Also, what do the tests not measure that we know fall under cognitive abilities?

Section 4: IQ Tests and Their Purpose: Strengths and Limitations

Kovács: That’s an interesting question. If we consider creativity a cognitive ability, IQ tests do not measure it. Creativity is assessed using creativity-specific tests, but it is a much harder construct to define, operationalize, and measure with psychometrically sound instruments.

Sensorimotor abilities are another relatively underexplored area in cognitive ability testing, especially in young children. In my lab, we are conducting a research project on this topic. Our findings suggest that in preschool children, sensorimotor abilities—such as balance or other basic motor skills—are strong predictors of cognitive abilities required in school settings. Interestingly, these correlations diminish after about age seven. However, in preschoolers aged four, five, and six, sensorimotor abilities are significantly linked to skills like memory and the ability to focus, which are crucial as children begin formal education.

Sensory motor abilities and creativity are two areas that, while reasonably considered cognitive, are not measured by IQ tests. IQ tests have historically focused on educational settings and later workplace applications. The military was among the first workplaces to use intelligence tests to predict achievement or trainability. What schools and workplaces require has heavily influenced the development of these instruments.

Section 5: Standard Deviation and Interpretability of Scores

Jacobsen: People researching IQ might encounter terms like standard deviation, whether 15, 16, or other values, and lists of IQ scores—highest IQ score lists, historical figures, famous people, etc. What should people think critically about when they encounter these references? Regarding some of these popularized extraordinary IQ scores, what can we reasonably say about their accuracy? Specifically, how do high and low scores relate to rarity percentiles?

Kovács: That’s a great question. There are two parts here: one about standard deviation and the other about the interpretability of the range. The most common standard deviation is the 15-point standard deviation, which was established with the Wechsler scale. This is the standard IQ distribution you’ll find in textbooks. IQ is typically presented as a scale with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

Here’s how it works: your raw test score is standardized, converting it into a z-score, expressing your performance in standard deviation units. Then, we assign 15 points for every standard deviation. For example, if you score exactly one standard deviation above the mean, your IQ score will be 115. If you score two standard deviations above the mean, your IQ score will be 130.

You’re right, though, that other standard deviations are in use. For instance, some tests historically used a 16-point standard deviation. However, I’m unsure if that is still true with the Stanford-Binet scales. The Cattell scale, on the other hand, used to have a standard deviation of 24. As someone who has provided feedback on IQ tests, I find this variability somewhat frustrating.

Many people, understandably, don’t realize that IQ is simply a relative scale. Without a background in statistics, interpreting it can be confusing. IQ is not an absolute measure.

For example, you can express even something like height on an IQ scale. You do not need to, since height has an absolute zero, so we use absolute measures like centimetres. IQ, by contrast, lacks an absolute zero—it’s purely comparative. Everyone is compared to the mean, and differences are expressed in standard deviation units before being translated into IQ scores. But if you really want you can express height using an IQ-style scale. In this case it becomes a relative score. For instance, let us assume that the average height for Canadian males is 175 centimetres, with a standard deviation of 6 centimetres. If someone is one standard deviation above the mean, their “height IQ” would be 115. This approach standardizes the data for easier comparison.

Jacobsen: Centimeters work—we’re Canadian and use metric and imperial measurements.

Kovács: Perfect. So, if we continue with that example, a two-standard-deviation height above the mean—187 centimetres—would correspond to a “height IQ” of 130. Of course, this is just an analogy to explain how IQ operates as a comparative scale rather than an absolute measure.

IQ scores can always be translated back to standard or z-score scores. For example, if you’re just above one standard deviation above the mean, your z-score would be +1. If you’re exactly as tall as the average Canadian male, your height in a standard z-score would be 0. If you’re one standard deviation above the mean, your z-score is +1. Theoretically, you could translate that into an IQ scale, but why would you? There’s an absolute zero with height, so you don’t need to use a relative scale like IQ.

IQ, conversely, is purely a relative scale. If you know someone has an IQ of 150 but don’t know the standard deviation being used; you can’t determine if it’s three standard deviations above the mean or slightly less than two. For example, with a standard deviation of 24, an IQ of 150 represents something different with a standard deviation of 15. People often don’t realize the importance of standard deviation in interpreting IQ scores.

Section 6: Percentiles vs. IQ Scores: Simplifying the Complexity

At the same time, there’s this strange IQ fetish in society. For example, you often hear claims from celebrities—actors or actresses—saying they have an IQ of 180. These numbers are thrown around, but they lack context. In my experience, percentiles are far more useful and comprehensible for the general public.

If you have a normal distribution of scores, any z-score can be converted into a percentile or an IQ score. Theoretically, These measures are interchangeable, but percentiles are much easier for most people to understand. For instance, if you tell a parent their 12-year-old outperforms 95 out of 100 children of the same age, they will understand what that means. Similarly, if you say, “Your child has a better vocabulary than 98 out of 100 children their age,” it’s immediately relatable.

If you tell the parent that the 98th percentile corresponds to a z-score of +2 or an IQ of 130, it becomes more abstract. If you say their child has an IQ of 130, most people won’t know how to react. Should they be ecstatic? Perhaps they read in the paper that morning about a celebrity claiming an IQ of 190, and they might feel disappointed. In reality, an IQ of 130 is excellent—it’s in the top 2% and qualifies for Mensa membership.

If I were in charge, I’d eliminate IQ scores entirely and only use percentiles. In my experience, IQ scores create more confusion than clarity. Unless someone in this field understands the statistical nuances, they often misinterpret the scores. Since IQ scores can always be converted to percentiles, the latter is more intuitive and effective for communication.

On the other hand, it couldn’t be clearer to a parent if you say, “Your child outperforms 90 out of 100 peers,” or, “Your child is weaker than 80 out of 100 peers.” That immediately highlights whether a specific area is a strength or a weakness for the child.

Section 7: Diagnostic Contexts: The Importance of Comprehensive Testing

The other question was about the range of interpretable scores. Typically, all scores are normed against a sample, usually a few thousand people. For example, in a representative sample in the U.S., you might have 5,000 or 6,000 participants, with around 200 individuals for a specific age group, such as 12-year-olds. When you compare an individual to that age group, anything beyond one in 200 is based on extrapolation.

The more you project beyond your data, the less accurate the interpretation becomes. For instance, if someone claims a child is “smarter than one in a million,” but the comparison is based on only 200 children, that projection is highly speculative. Typically, scores within plus or minus two standard deviations from the mean are interpretable. A third standard deviation can also be meaningful, especially for individually administered tests that take significant time to complete.

IQ scores are often calculated as scores derived from multiple subtests. If someone scores in the top 2% across five subtests, the likelihood of that occurring across all subtests is much rarer than 2%. To explain this with an analogy: imagine you’re looking for people who are taller than 98% of Canadians and have driven more miles than 98% of Canadians. The probability of finding someone who satisfies both criteria is much smaller than 2%.

Similarly, if someone scores very highly on multiple subtests, it provides a stronger basis for interpreting their overall IQ as being exceptional. By contrast, if someone scores high on just one test, that result is more likely to be “noisy,” with a larger margin of error.

In statistical textbooks, normal distributions are usually illustrated up to plus or minus three standard deviations because this range covers 99.7% of the entire distribution. Only 0.3% of scores fall outside this range—0.15% on each end. For example, anything above three standard deviations would represent about 3 individuals out of every 2,000. That’s why illustrations of normal distributions in textbooks typically stop at three standard deviations; beyond that, the probabilities become increasingly rare and harder to measure accurately.

Up to plus or minus three standard deviations is meaningful and reliable. I know there are groups like the higher sigma societies, but I don’t want to comment. I’ll leave that to someone you might interview from those societies. For the record, what I’m describing here is what you’ll find in standard statistical textbooks. Reliable and valid testing generally falls within plus or minus three standard deviations. Beyond that, scores become far less reliable.

I’d be skeptical of scores above +3 standard deviations and specially above +4. A score of +4 can be equivalent to one in a million. For instance, someone claiming, “My child is smarter than 999,999 other children,” raises the obvious question: how do you know?

Section 8: Multiple Intelligences and Alternative Theories

Jacobsen: These issues often tie into statistical limitations, such as sample size and whether the test was properly proctored. Then, there are potential conflicts of interest. For example, if someone takes a test designed by someone they know, the results could be biased. Setting aside those issues, we’ve covered a lot so far: definitions of intelligence, the scope of IQ tests, reframing to cognitive abilities, standard deviations, and reliable ranges. What about the context in which these tests are proctored? For example, tests developed with significant investment and large sample sizes are conducted in secure environments where answers aren’t leaked—what is the importance of those measures when trying to measure what IQ tests aim to assess?

Kovács: In short, high stakes. Suppose you want an elaborate and thorough measurement, especially when the stakes are high. In that case, ensuring the test is secure, properly administered, and statistically sound is essential. This is particularly critical in diagnostic contexts.

One high-stakes example is the death penalty in the U.S. Individuals with an IQ below 70 cannot be sentenced to death. Determining whether someone’s IQ is below this threshold becomes a matter of life and death—the highest stakes imaginable. While that’s not my area of research, it’s an extreme case where the reliability of IQ testing carries enormous weight.

More commonly, professionally proctored IQ tests are administered for diagnostic purposes, particularly in school settings. In the U.S. alone, millions of individually administered IQ tests are conducted yearly. These tests help identify cognitive strengths and weaknesses to guide educational and developmental interventions.

Section 9: The g-Factor: Index, Not Ability

A comprehensive profile, derived from a range of subtests, is so important. It provides a detailed view of strengths and weaknesses. For example, one of the most common recommendations by school psychologists is to suggest that a child be given extra time on tasks or exams.

Imagine a child with a profile showing excellent fluid reasoning (nonverbal problem-solving), strong verbal ability, and strong spatial ability but only slightly above average working memory and average perceptual speed. This profile often leads to frustration because the child’s abilities outpace their processing speed. In other words, their strengths cannot fully compensate for the slower speed at which they process information. This kind of detailed profile allows a school psychologist to make targeted recommendations to address the child’s specific challenges.

Individually administered tests are resource-intensive, typically taking one to one-and-a-half hours of a psychologist’s time in a one-on-one setting. This level of investment is far greater than administering a group test to 30 students, so it’s generally reserved for high-stakes situations. For instance, if a child is underachieving, frustrated, or showing signs of learning difficulties, then creating a full-ability profile is worth the investment. A detailed profile highlights individual strengths and weaknesses. It is far more useful for diagnostic purposes than a single overall score.

When I teach this, I often use an analogy to explain the limitations of an overall IQ score. Imagine visiting your doctor and receiving a detailed lab analysis of your blood sample. You see values for glucose levels, cholesterol, vitamin levels, and so on. Imagine the doctor told you, “Your health IQ is 70.” What would you learn from that? You’d know you’re in trouble—only 2% of people your age are less healthy than you—but it wouldn’t help you or your doctor determine what’s wrong or how to address it.

That’s the issue with relying solely on an overall IQ score. It’s like receiving a “health IQ” score that says you’re less healthy than 95% of your peers. While that might motivate you to worry, it doesn’t provide actionable insights. Similarly, while overall IQ scores can be useful to an extent—such as for Mensa membership, where the goal is to identify the top 2% of cognitive performers—they don’t provide the diagnostic depth necessary to understand and address specific challenges.

A health quotient (HQ) might be useful if your goal is to create a society comprising the healthiest 2% of people. However, if someone is unhealthy, an HQ score won’t help them. What they need is a detailed diagnostic to identify the specific problem. That’s why we use detailed tests and invest significant resources and time to assess a child individually and create a profile of their strengths and weaknesses.

Jacobsen: These are important cautionary tales about interpreting results. What about multiple intelligences, Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence, and the g-factor? While there’s no general consensus, what is the prevailing view?

Kovács: These are all controversial topics. Regarding multiple intelligences, I think Howard Gardner’s work critiques the educational system more than a true theory of individual differences. Gardner has never shown much interest in rigorously measuring these intelligences. Essentially, his theory advocates focusing on children who might not be conventionally “smart” but excel in areas like social skills or the arts. It’s an example of extending the concept of intelligence, which is valuable in its own way. However, Gardner hasn’t developed reliable assessment tools for most of this proposed intelligence.

Whether we should call someone “intelligent” for having exceptional interpersonal skills despite not being conventionally smart is a matter of perspective. I’ll leave that judgment to others. As for the g-factor, that’s closer to my area of research. My work focuses extensively on interpretations of the g-factor, and I’ve published on this topic. We have a framework called the Process Overlap Theory, which explains the g-factor without requiring the assumption of a general intelligence or overarching ability. Naturally, I’m biased because this is my research field. Still, I see the g-factor as a summary or index score of separate cognitive abilities.

The g-factor is statistically advantageous in many ways. While it doesn’t represent a single ability, it’s a latent construct useful for certain purposes. For example, suppose you’re conducting large-scale sociological research and want to study how cognitive functioning predicts income. In that case, the g-factor is a highly effective tool. In that context, it doesn’t matter whether someone excels in working memory, perceptual speed, or vocabulary—the overall level of cognitive functioning matters.

However, the utility of the g-factor depends entirely on your purpose. For diagnostics, the g-factor is not particularly helpful. Like the HQ analogy—it provides an overall score but doesn’t tell you much about specific strengths or weaknesses. If your goal is to diagnose and support individuals, identifying patterns of cognitive strengths and weaknesses is far more informative. On the other hand, if you’re studying broad trends, such as the relationship between cognitive functioning and socioeconomic outcomes, the g-factor is invaluable.

If you want to predict someone’s salary based on their cognitive abilities, overall scores or indicators like the g-factor are very useful. However, I don’t see the g-factor as a proxy for a single “general intelligence.” Instead, it’s an index score calculated from various distinct abilities.

Jacobsen: That’s a very interesting perspective. I hadn’t heard it framed as an index at a sociological level rather than as a generalized commentary on a larger sociological construct. Viewing it as an index aligns with your emphasis on cognitive abilities about different factors. That makes the research clearer, too.

Kovács: Exactly. I’m glad it makes sense.

Section 10: Final Reflections: Caution and Clarity in Assessment

Jacobsen: Any final important things people should remember when they look at scores or assessments?

Kovács: That topic would take over a minute to address, so I’ll leave it at that for now. If that’s okay with you, my part is complete. I look forward to seeing the transcript.

Jacobsen: Excellent.

Kovács: Thank you for your time and patience.

Jacobsen: I truly appreciate this conversation.

Kovács: Thank you so much. Cheers!

Discussion

The interview between Scott Douglas Jacobsen and Dr. Kristóf Kovács provides a detailed exploration of how modern psychology understands and measures cognitive abilities. Dr. Kovács challenges the traditional notion of “intelligence” as a singular construct, emphasizing instead the pluralistic nature of cognitive abilities such as fluid reasoning, crystallized knowledge, perceptual speed, and working memory. By moving beyond a single “IQ” score, he advocates for a more nuanced view that can guide targeted educational and diagnostic interventions. A recurring theme in the conversation is the distinction between intelligence as a broad concept and IQ scores as comparative, standardized metrics. Dr. Kovács underscores that IQ testing, while not perfect, remains one of the best available tools for evaluating cognitive performance—reminiscent of Winston Churchill’s remark about democracy being the “worst form of government except for all the others.” The interview critiques the widespread fetishization of extreme IQ scores, highlighting that many of these extraordinary claims lack robust statistical grounding, especially beyond three standard deviations from the mean.

Another significant thread is the question of what IQ tests fail to measure. Dr. Kovács points to creativity and sensorimotor abilities as cognitive functions often overlooked in conventional testing. Additionally, the conversation addresses multiple intelligences (e.g., emotional or spiritual intelligence) and how broadening the definition of “intelligence” can move us away from precise measurement, potentially conflating distinct skill sets under one umbrella term. The importance of standardized, proctored testing environments also features prominently. High-stakes scenarios—such as determining if an individual’s cognitive functioning meets legal thresholds—demand rigorous procedures to ensure both validity and reliability. Dr. Kovács illustrates how a more detailed cognitive profile, built from a series of subtests, can offer actionable insights. By examining strengths and weaknesses, educators and clinicians can better tailor interventions for individual needs.

Ultimately, the conversation highlights that while IQ tests serve as valuable predictors in large-scale sociological research—such as forecasting educational or occupational outcomes—their utility in diagnosing and guiding individuals hinges on deeper, more granular analyses of cognitive abilities. Dr. Kovács calls for a balance between recognizing the broad applications of IQ tests and acknowledging the complexity of human cognition, urging educators, psychologists, and policymakers alike to interpret scores with both caution and context in mind.

Methods