A new patron-exclusive episode is now available examining the life of Joseph Habersham, Postmaster General under Washington and Adams. Not a patron yet but want to get access to this content? Follow the link to learn how! #history #POTUS #PostOffice https://www.patreon.com/posts/p002-joseph-131304664?utm_medium=clipboard_copy&utm_source=copyLink&utm_campaign=postshare_creator&utm_content=join_link

#postOffice

#AusPost seem to have fallen over re: #deliveries to my neck of the woods since last week.

Items that were en route to my local #PostOffice for delivery last Thursday & Friday have vanished in #tracking.

An enquiry as to their whereabouts has updated tracking to “delayed” & an update to delivery of 2 weeks on their due date since I asked where they are!

#WTF!?

The thread about Edinburgh first Penny Postal service, house numbers and street directories

This thread is a write-up of a talk given for the Edinburgh World Heritage Trust in June 2023. It has been split across multiple sections for ease of reading.

This vacance is a heavy doom

On Indian Peter’s Coffee Room,

For a’ his china pigs are toom;

Nor do we see

In wine the sicker bisket’s soom

As light’s a flee.The Rising of the Session, Robert Fergusson

In this verse, the “lights” that Robert Fergusson refers to are the men of law of the Court of Session in 18th century Edinburgh, fleeing the city in the summer to their country houses, away from the stench of the Old Town. Indian Peter’s Coffee Room was a small establishment within the Parliament Hall itself, the outer house of the Court of Session, Scotland’s supreme civil court, it’s patrons being the men of the law who conducted their business there. The “china pigs” are the drinks vessels and are empty now the customers are gone, and the “sicker biskets soom” is the dipping of small, sweet biscuits into the wine.

Part 1. Indian Peter.

So who was “Indian Peter”? Before we can go any further in our story it is very important to understand some of his long and complex life history, as it is relevant to his character and his motivations in later life. Indian Peter was Peter Williamson, born 1730 in Aberdeenshire. He was the son of a farmer and as a boy was sent to live with an aunt in Aberdeen. Aged 13, while hanging around the quayside in that city, he was tricked aboard a ship under false pretences and imprisoned. Not long thereafter he was part of a cargo of 70 abducted boys and girls who were taken to North America on board the ship Planter to be sold as a slave labour. On arrival in the New World, the vessel was shipwrecked, and the children were abandoned to their fate. When it was clear that they had survived, their captors returned and took them for sale. Peter was sold for £16 to a Scots settler who had arrived in America by the same method he had. He was as fortunate as his circumstances could allow him and his new master treated him well and schooled him.

The master died when Peter was aged 17, leaving him his horse, saddle and £120. With little reason to return to Scotland, Williamson settled down to farm and marry. His wife’s family were planters of some means and he was given a good property to work by his father-in-law. His recent good fortune however took a turn for the worse in 1754 when the farm was raided and burnt to the ground by the native Lenape people: the Delaware Indians. His wife was absent at the time but Peter was taken captive and forced to carry off his best possessions as booty. He spent some time as a captive with the Delaware, acting as a porter. During this experience he claimed to have been tortured and to have seen other settlers tortured or killed, but also picked up some of their customs (which he would later adopt and which would personify him in Edinburgh).

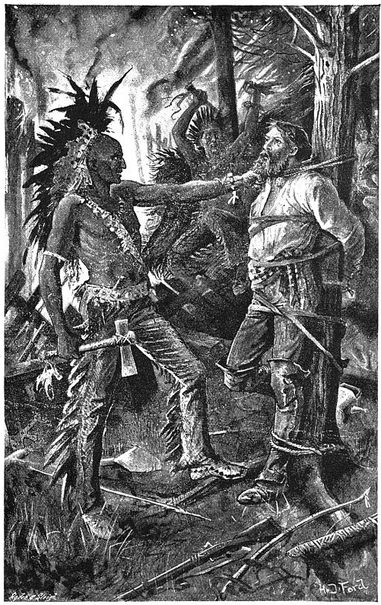

“The Indian Threatens Peter Williamson”, from The Red True Story Book, 1895, an illustration by H. J. Ford

After 4 months of captivity, Williamson seized a night time opportunity and escaped under the cover of the noise and activity of wild hogs and managed to return to the planter community. Tragically he found that his wife had died two months previously. Motivated by loss or revenge, he joined a British regiment in the Seven Years War to fight against the French and their Indian allies, serving for 18 months before being captured and imprisoned for the third time in his life in 1756 at the Battle of Oswego.

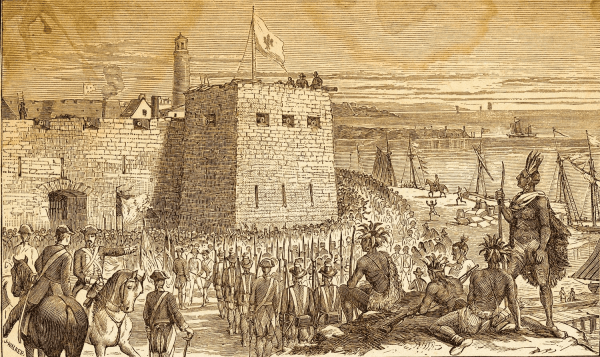

The Battle of Fort Oswego, where a French, Canadian and Indian force overwhelmed British defenders. Photogravure by John Henry Walker, 1877, from Journal de MontréalWounded, he was sent to a camp in Quebec he was soon fortunate to be repatriated to Britain in a prisoner exchange and that same year landed a broken man in Plymouth. Paid off from the army due to injury with a paltry sum, he headed for “home” in Aberdeen but ran out of his funds in York. It was here he ingratiated himself with some gentlemen who published an account of his life’s adventure in a book called “French and Indian Cruelty”. The book was a success and with the money he made from it he was able to return to Aberdeen, intending to sell his book and settle down. However the Aberdeen magistrates, who he had accused of being complicit in his abduction as a boy (and that of hundreds of other children) had other ideas and had him arrested and his books impounded. To secure his release, he had to agree to sign a retraction of his story and accusations, to pay a fine of 10 shillings, and to have his books publicly burned by the town executioner.

Spurned by his home town, he headed south to Edinburgh where he ingratiated himself amongst some men of the law. Appalled by his tale, they agreed to help him sue the Magistrates of Aberdeen. Williamson was able to build up a convincing legal case, supported by many witnesses, and surprised everyone by winning. He was awarded £100 in damages and his expenses. The magistrates, represented by one Walter Scott (the father of Sir Walter Scott) appealed, and lost. Settling in Edinburgh with his award, he re-published his book and set himself up as a tavern keeper on the Parliament Square. A sign over the door of his establishment reputedly read “PETER WILLIAMSON, VINTNER FROM THE OTHER WORLD“. When business was slow, he would don the guise of a Delaware Indian which he had managed to procure and perform a “war dance” in the High Street. Thus he became an accepted eccentric in the city’s social scene as “Indian Peter“, “Peter Williamson of the Mohawk Nation” and the “King of the Indians“.

He moved his business into the Parliament Hall as a coffee house, with the men of the law being his primary clientèle. He was also popular amongst the literary men and as well as Fergusson his shop was patronised by James Boswell and Sir Walter Scott and he was a correspondent with Ben Franklin.

“The Parliament Close and Public Characters of Edinburgh, Fifty Years Since”, in the style of John Kay, 1849, the bustling legal heart of the city in Williamson’s timeIndian Peter was not content to just live the life of a coffee house keeper and local celebrity however, and showed an irrepressible entrepreneurial streak. During a visit to London, he bought a portable printing press, which he returned to Edinburgh. Unable to break the closed ranks of the city’s printers for training, he instead taught himself how to operate it and went into business as a printer, publisher and book seller. At times he also ran a small bank (offering to exchange bank notes for “ready money, books or coffee” and even ran a lottery offering two squirrels as the prize!

Transcription of one of Williamson’s bank notes, which was probably more of a joke and gimmick amongst his friends than a serious business propositionThe name “Ready Money Bank” was a jibe aimed at some of the Scottish banks, which at this time issued “option clause” notes, where your note, when presented for redemption, was at risk of being paid out not in cash but for a note of another bank.

Peter Williamson. A caricature by John Kay from 1791 called “Travells eldest son talks with a Cherokee chief” © Edinburgh City LibrariesBut it was in 1773 where Williamson’s two greatest contributions to the City are made; he establishes a Penny Post (only the second such service in the British Isles) and he began compiling and publishing street directories of the city and its principal residents. It is now that our story really begins. So why are these innovations of his so important? Firstly, they allowed anyone to send communications within the city, quickly, reliably and (relatively) cheaply and they told you to whom to send it and where! It is the beginning of a modern communication network within the city, a city which was just beginning to break free of the ancient confines of the Old Town and across the Nor’ Loch valley to the opportunities, space and clear air of the New Town. The Postal Museum states “in particular, the Edinburgh Penny Post [was] influential in establishing the pattern for the Provincial English Penny Posts that followed.“

Part 2. The Edinburgh Penny Post

Before the advent of the Edinburgh Penny Post, messages were carried around the city by your own servants or you could hire a Caddie (the town’s licensed class of porters and messengers) or pay a trustworthy child to run the errand. It was also the job of the Caddie to know everyone and everything, they acted as an informal news, communications and intelligence network.

An Edinburgh Caddie, by David Allan. Note the numbered badge of his trade, his licence to work, worn on the jacket breast. CC-by-NC National Galleries ScotlandThe first Penny Post was established in London by William Dockwra in 1680, but he quickly fell foul of the General Post Office (GPO) monopoly and the fact his service was thought to be carrying seditious letters, it was seized from him, his patent forfeit and was ordered to pay £2,000 compensation. But you can’t keep a good idea down, and in 1765 an act was passed (Postage Act 1765) permitting licensed Penny Posts in provincial towns and cities. Although Williamson established his post in 1773, it was not until 1776 that he was formally granted permission from the Postmaster General for his service. His network in the city operated from 9AM to 9PM each day and for an English penny (paid up front, or on delivery) you could send a letter or small packet within one English mile of the Mercat Cross, north, south, east or west, and to Leith. The service to the latter, the city’s port, operated 8 times a day in both directions, between 8AM and 7PM.

Williamson’s Penny Post stamps, for mail sent payment on delivery (left) or paid in advance (right). These stamps are thought to have been made by Williamson himself from his experience of his printing press.Four postmen were employed, who carried a hand bell to advertise their presence and wore a service cap with the name “Williamson’s Penny Post” painted or embroidered on it in silver and who were paid 4 shilling and 6 pence per week. The story goes that the caps were numbered 1, 4, 8 and 16 to make it appear as if the business was 4 times bigger than it really was. Knowing Williamson’s inventive abilities for self promotion, this does not seem that far fetched to be true. Of only one of the postmen do we have any sort of an insight, a highlander by the name of Donald Mackintosh who hailed from the vicinity of from near Blair Atholl and Killiecrankie. Mackintosh would have been in his thirties at this time and his task was described as a “his “useful though humble vocation”. He would later rise to prominence in his own right as an Episcopalian clergyman and a scholar of Scottish Gaelic.

Illustration by Will Nickless, 1962, purporting to show one of Williamson’s Penny Post men delivering a letter.It was not only the four postmen who collected letters, they could also be dropped off at a network of 18 “receiving houses” in the city and Leith, which were pre-existing shops that Williamson had convinced to act as post offices. His carriers would call at them on their rounds to collect any deposited letters for onward delivery. He listed these in the directory, making it relatively easy to plot them to a map. At this stage the New Town could be served by a single receiving house on St. Andrew Street, the Canongate and southern suburbs both each by a single house too. The 1775 directory had a slightly refined network, with the concentration in the centre of the High Street reduced, additional houses in each of the Canongate and Southside and an additional house in Leith.

Williamson’s network of receiving houses in 1773-74, as listed in his directory. The red triangle is the GPO on North Bridge. Overlaid on Kincaid’s plan of Edinburgh (1784) and Wood’s plan of Leith (1777), both reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandMuch of the business for the Penny Post came from the men of the law that Williamson was already ingratiated with – reflected in the concentration of receiving houses around the Parliament Square – as it was they who had a business need to communicate quickly and frequently across the city. They knew him well: he was both in their fold but an outsider in the city hierarchy; he had long overheard their intimate business discussions in his tavern and coffee house without making a nuisance of himself. He was therefore a man to be trusted with their secrets.

A letter sent by Williamson’s Penny Post, to Mr William Brodie at Mr Robert Donaldson’s, Writer to the Signet, New TownBut it was not just the city’s lawyers and merchants who found use for the Penny Post. It offered an important new opportunity to women, as for the first time they could begin to converse privately through writing, away from the prying eyes of the servants who up until that time would have been entrusted with carrying letters. One exceptional romance is recorded as taking place discretely though Williamson’s delivery network; that of Robert Burns and Agnes Maclehose, known either as his Nancy, or Clarinda. In all, this flourishing written courtship amounted to 88 letters, carried by the Penny Post, and what Sir Walter Scott described as “the most extraordinary mixture of sense and nonsense, and of love human and divine, that was ever exposed to the eye of the world“. Burns, bedridden at the time after injuring his leg, was lodgning near the St. Andrew Street receiving house in the New Town and Nancy was but a short distance from the branch on Chapel Street, just beyond the Potterrow. On some days the couple would exchange as many as two letters each, in both directions.

Mrs Agnes McLehose, c. 1840s, Artist unknown. CC-by-NC National Galleries ScotlandEven at this early stage, in a relatively small city, the correct addressing of mail was an issue for the Penny Post and Williamson had to print begging notices in his directories pleading for letters to be clearly and non-ambiguously addressed.

To The Public, a notice in Williamson’s directory asking for mail to be clearly addressedOne of Williamson’s receiving houses was the premises of John Wilson, a bookseller who had one of the shops in the colonnade in front of the Royal Exchange (now the City Chambers). Wilson also sold Williamson’s directories and happened to be his father-in-law. He is absent from the later versions of the list of Receiving Houses. This is with good reason; Williamson had separated for his wife – Jean Wilson – having accused her both of serial adultery and also of interfering with the Penny Post and misappropriating its profits. She had also cut him off from access to his children, including the eldest daughter who made a reasonable addition to the family income as a mantua maker (specialising in making ladies’ mantles) and with her father had set up a rival operation to try and run Peter out of business! But if the story so far has taught us anything, it is that when he was down, Peter Williamson was never out, and he would come back fighting. Once more he turned to his friends in the legal establishment and he built up an indestructible case against his wife. He cited nineteen different servants, doctors and lawyers as witnesses; she put up none in defence. She tried to get Williamson to pay for her legal defence, the court found that she had left him in forma pauperis (in the manner of a pauper; unable to pay) which further damaged her reputation. Williamson was granted divorce in his favour in March 1789 and regained control of his businesses and custody of his children. To recoup his losses from this case, he published a sensational account of his wife’s “crimes” against him, which having been proven in court he had no need to worry about being sued over.

In all, Williamson would run his Penny Post successfully for 19 years, it returning him on average a profit of £50 per annum (about £6,500 in 2023). However the reality was that he was ageing, and his energy for self promotion, fighting off the competition and keeping his postmen in check was waning. In 1790 Francis Freeling, the secretary to the Postmaster General, visited Edinburgh and observed the Penny Post in action. Suitably impressed, on his return to London he recommended to his superior that the GPO should take the service over and run it for itself. A younger Williamson may have tried to resist, but he sensibly acquiesced to authority and in 1793 the GPO took over the service. But true to form, he did not hand it over before overstating both his age and his financial dependence on the Post in a letter to the Postmaster General, ensuring he received a pension of £25 for life in return for relinquishing control.

A Victorian postman of the GPO in 1820, from the cover of the sheet music for a popular song “The Postman’s Knock”.We have also to beg your Lordships permission to authorise us to allow Mr. Williamson of Edinburgh £25 per annum, he having long had the profits of 1d. a letter on certain letters forwarded through his receiving house in Edinburgh, which he will lose by our having established a penny post there.

Passage from a letter from the Postmaster General to the Treasury, requesting Williamson’s pension, 17th July 1793

The GPO quickly adapted the service to their own practices, cutting down both the number of receiving houses – from 18 to 9, the number of collections to 5 per day and the number of deliveries to 3; but at relatively fixed times of morning 98AM), early evening and late evening (7PM). They increased the number of postmen to 20 and by 1817 there were 30.

Part 3. Williamson’s Postal Directories

Williamson’s other great innovation in 1773-74 was the collation and publication of a postal directory for the city. (You can view this directory for yourself here, on the website of the National Library of Scotland.) He described it himself thusly:

An alphabetical list of the names and places of abode of the members of the college of justice; public and private gentlemen; merchants, and other eminent traders; mechanics and all persons in public business; where at one view you have a plain Direction, pointing out the Streets, Wynds, Closes, Lands and other Places of their Residence, in and about this Metropolis. Together with Separate Lists of the Magistrates, Court of Session and Court of Exchequer, the Constables of Edinburgh, Canongate and Leith, Carriers, etc.

Descriptive preface to Williamson’s first postal directory

This was the first comprehensive directory of anyone who was anyone in the city, what they did and where they were based. Williamson also includes useful information such as the boundaries of parishes, the members of the town council, the constables, and lists of carriers, the days they depart and where they operated from and to, and of course a list of his own Penny Post receiving houses. He operated this as a vertically-integrated business; he gathered the contents, published and printed it on his own presses, used it to advertise his Penny Post system and sold it himself at his own bookshop.

An extract of the first 4 pages of entries under the letter A for Williamson’s first Postal Directory of Edinburgh, 1773-74. CC-by 4.0 National Library of ScotlandTo produce the publication, Williamson claimed to have visited every address in the city to compile details of the occupants and their professions. Many were suspicious of his motives and would not consent to give their details, which resulted in an incomplete listing that has a large appendix of late additions, which made it hard to use. A unique and cumbersome feature of the first directory was that within each letter of the alphabet, he sub-organised the contents by profession. While this makes it harder to find what you are looking for, it is a fascinating insight into the rigid social and professional hierarchies of the city at this time and perhaps the relative esteem with which Williamson himself held each class of profession. In all, the directory lists 3,914 individuals and 130 different occupations, some of which I have grouped together for convenience (e.g. shoemakers and clogmakers; barbers, wigmakers and hairdressers). The table below ranks professions with the the highest 15 and lowest 15 positions in the directory in the 1773-74 directory.

Rank“Highest 15” professionsRank“Lowest 15” professions1Advocates (barristers)15Baxters (bakers)2Clerks/ Writers to the Signet14Fleshers (butchers)3Lords’ and Advocates’ Clerks13Barbers, Wigmakers & Hairdressers4Writers (solicitors)12Candlemakers5Procurators (prosecutors)11Shoe & Clogmakers6Exchequer10Taylors & staymakers7Physicians9Weavers8Ministers8School masters, teachers, academics9Noblemen, Gentlemen, Ladies and Gentlewomen7Milliners & Mantua-makers10Bankers6Excisemen11Merchants5Stablers12Grocers4Engravers13Ship-masters3Bookbinders14Surgeons2Confectioners15Brewers1Room setters (letting agents) & boardersThe contents of this directory also allow us to easily total up the relative frequency of the different occupations amongst the entries and plot them as a chart (below). From this we can observe that a full quarter of the entries are for the Incorporated Trades (i.e. the officially recognised and established trade and craft associations of the city, such as bakers, butchers, goldsmiths, taylors, weavers etc.). A further fifth are the men of the law, and a tenth are the merchants. This is fully unsurprising for a city built upon the prosperity and power of these groups. We can see that the nobility, by volume, are a relatively small component, and while print, medicine and education are relatively small contributions, these are three industries that will flourish in Edinburgh in the next 100 years and that the city will become synonymous with.

There are no street numbers in any of Williamson’s Directories until 1784. Prior to this, locations are simple, relatively vague and purely descriptive such as “head of Baillie Fyfe’s Close” or “Grassmarket, south side“. The introduction of numbers at first was just for the New Town and small parts of the Southside of the city (Nicolson Street and Chapel Street), the exception being James’ Court, which at the time was an exclusive address.

Although he originally intended to produce only a single directory, in the end they were such a success that Williamson published them for 17 years. For his final directory, that for a two year period of 1790-92, he subcontracted the printing out to Campbell Denovan, but retained the rights to sell a certain volume of copies exclusively. From 1794 the Edinburgh directories would be published by Thomas Aitchison, and then again the Denovans in 1804 before the Post Office itself took over in 1805 (although the printing was still local in Edinburgh). These later directories conform very closely to the style and structure first set out by Williamson, a testament to his ability to bring a systematic and ordered approach to what was a very chaotic city.

Williamson exercised this latter talent in what is a remarkable document, known either as “Williamson’s Broadside” or “An Accurate View of All the Streets, Wynds, Squares, and Closes of the City of Edinburgh, Suburbs, and Canongate, on both sides of the High-street, from the Castle to Holyrood-house, agreeable to the names they are at present known by, together with those in the New Town and Leith.”. This large printed page was a comprehensive list of all the closes and streets of the city and Leith, and their relative order and position to each other and the principal landmarks. An invaluable reference then, it is even more so now for modern eyes interested in where the old streets and closes were located and what names were in use. Ever the man with an eye on business, the corners of the page advertise other products and services sold by Williamson such as his Penny Post, stamps for marking books and linen, printed funeral announcement cards, and a form of fortune-telling cards he printed.

Williamson’s Broadside, folded up. You can view the full sheet at the below link to the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club.You can view the full broadside for yourself in a chapter that starts on Page 261 of volume 22 (original series) of the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, published in 1939, which is digitised online here.

With his Penny Posts in the hands of the GPO and his directories with Campbell Denovan, Peter Williamson retired with his pension and what was left of his profits from these businesses (he claimed his wife and father-in-law had robbed him of fully three quarters of the latter) and took up a tavern in the Lawnmarket. He died in January 1799, and was buried in “The full panoply of a Delaware chief” in the grave of Mr. J. Scott, some distance north-east of William Nicol, beneath a stone surmounted by an urn.

Part 4. Street Numbering and Re-Numbering

Street numbering in Edinburgh started in the early 1780s, Williamson’s directories first reflecting it in 1784. It progressed as the New Town itself expanded, and the practice slowly began to spread to other parts of the city. Streets with only one side were simply numbered in a series from one upwards. However at this time there was no agreed manner by which to number doors in streets with two sides (which was most of them!) Three principal methods existed and all were implemented and existed side-by-side with no consistent approach – indeed the New Town used all three!

- The first method used is that with which we are familiar today: one side of a street has even numbers and the other has odd numbers, and the numbers increase in series as you move along the street.

- The second method was a “there and back again” method, whereby numbering progressed in an increasing series of odd and even numbers from number 1, up one side of the street, to the end, and then back down the other side. This meant that the highest and lowest numbers of the street were opposite each other. Nicolson Street was one street that used this method of numbering.

- The third method was that of “northside / southside”. In this system, the street sides were named north and south (or east and west) and each side was numbered from 1 upwards in a continuous series. As a result, each number was duplicated, No. 1 North Side and No. 1 South Side were opposite each other, and without specifying which side of the street a letter was intended for or an advert was referring to one could easily end up with the wrong door.

By 1811 the system (if you could call it that) was in chaos, as not only was there no consistent methodology but demolitions, new buildings and subdivisions had caused numbering sequences to become haphazard and out of sequence. Something had to be done, and done it was. Despite a curious lack of historical record in either the City Archives or contemporary newspapers, on Whitsunday 1811 there was a wholesale and systematic renumbering of much of the City which had been numbered up to that point. The Caledonian Mercury contains one of the few examples evidencing this wholesale change:

Caledonian Mercury – Saturday 27 April 1811The new numbering system split the city into quadrants, using the east-west axis of the High Street and the north-south axis of the Bridges and St. Andrew Street (shown as the yellow line on the map below). Within each of these quadrants, streets with two sides would be numbered with odd doors on one side and evens on the other, and the number series would increase as you moved away from the axis (shown by the blue lines on the map below) – so in theory the numbers always increase as you move away from the centre point of the quadrants. The system placed the odd numbered doors on your right and the even numbered doors on your left as you walked along any street in the direction of increasing numbers.

The street re-numbering axes and directions of increasing numbers, overlaid on a map of Edinburgh by John Ainslie, 1804. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThere were of course exceptions to the system. The Grassmarket ran in the “wrong” direction, retaining its former door numbering order which increased towards the axis. The Cowgate passes underneath the South Bridge axis, so one half of it (the western end) was inevitably not going to be able to conform. The east west axis – the “Royal Mile” of the Canongate, High Street, Lawn Market and Castle Hill – was numbered in two sequences. The first was the Canongate, uphill from the palace of Holyroodhouse to old burgh boundary with Edinburgh at the Netherbow. The High Street, Lawnmarket and Castle Hill were numbered into one continuous uphill sequence from the Netherbow. It is for this reason that to this day, the Lawnmarket street numbers start at 300 (evens) and 435 (odds), and there are no numbers 2 to 298 or 1 to 433 Lawnmarket. Similarly the numbering on the Castlehill starts at 348 (evens) and 525 (odds). Other oddities include Great King Street, where the evens are on your right instead of the odds, and South Bridge, which retained the old “there and back again” numbering and still does to this day (this is despite the North Bridge and Nicolson Street, its northern and southern extensions, being re-numbered)

The street numbering of the South Bridge, on Ainslie’s Town Plan of 1804. The map has been rotated by 90 degrees for clarity. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe First New Town of Edinburgh, that part planned out by James Craig and that existed prior to 1811, conforms almost perfectly to the rules of the 1811 numbering system. On the map below, the red arrows show the street numbers ascend in the correct directions. The squares of Charlotte and St. Andrew are ordered in a clockwise manner. The Northern or Second New Town, the section north of Queen Street Gardens was developed from 1800 onwards so conformed to the scheme too (with the exception of the already noted Great King Street). The “Moray Feu” extension of the New Town, shown in the blue arrows, was developed from 1822 and conformed with the 1811 scheme, with the anomaly of Great Stuart Street, which is interrupted by Ainslie Place, so you have to pass through the latter to get to the other side of the former.

Edinburgh map by Bartholomew, 1891. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe West End (green arrows on the map above) was feud from the estate of Walker of Coates from 1813 onwards and took its own, haphazard approach as it developed in a piecemeal manner. Queensferry Street is numbered in a “there and back again” nature; the numbers on some streets ascend in the right direction, but with the odds and evens on the wrong sides; Drumsheugh Gardens increases in an anti-clockwise manner, and towards the Dean Bridge; the street is Lynedoch Place on one side and Randolph Cliff on the other, each with its own numbering sequence. Princes Street in the First New Town posed an interesting test for the system. We think of it as being only a street built on one side, but there is of course a single block built on the south side at its eastern end. This was originally individual properties and prior to 1811 these were numbered in their own series as “Princes Street South Side”. The principal, northern side of the street did not need the geographic qualifier.

The east end of Prince’s Street as shown on Kincaid’s Town Plan of 1784. Note numbers 1-5 on the south side, and 1 upwards on the north. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandThe 1811 re-numbering decided to treat the street as if it had a single side, with numbers 1-9 allocated to the south side, and the northern side numbered from 10 upwards. This arrangement was broken in 1898 when the block to the south was demolished to make way for the North British Railway Hotel (now The Balmoral), which took the number 1; numbers 2 to 9 Princes Street have therefore never existed ever since.

East End of Princes Street, as shown on Kirkwood’s Town Plan of 1819. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandIn 1826 it was reported in the local press that a wholesale renumbering of the “suburbs” has been completed, that street names had now been painted on the corners and that a move was being made to begin painting up the names of the closes of the Old Town. The considered order of this new system was not to last however. By 1826, properties on Princes Street were plagued with subdivision of the original houses into commercial premises, requiring the Town Council to approve the use of A, B, C etc. to distinguish each new door from its original number. By 1856, the Cowgate was said to be in “a most hopeless state of darkness” and in 1869 the Lawnmarket was “greatly confused and unintelligible”. However a systematic approach was never taken again, and renumbering thereafter took place on a case-by-case basis, approved by a special council committee. Exceptions and curiosities still prevail however. Summerhall Place, for instance, was re-numbered as 5 to 13 Causewayside in 1935. However the uproar this provoked in its residents caused it to be renamed back to Summerhall Place, but with the numbers in the Causewayside sequence retained: to this day the latter street still starts its numbering of odd doors at number 15.

Part 5. Street Naming and Re-Naming

Street names, even those we are most familiar with, do not always remain the same forever and some change before they are even built. An early copy of James Craig’s original printed plan of the New Town from 1767 has the streets we know now as Princes, George and Queen referred to instead as simply the South, Principal and North; the names were yet to be decided.

Copy of James Craig’s 1767 New Town Plan © City of Edinburgh CouncilA later copy of the same year, which James Craig apparently took to London, had named these streets as St. Giles Street (after the patron saint of the City), George Street (for the King, George III) and Forth Street, an unofficial innovation of Craig’s own doing, probably on account of the views it commanded towards that body of water. The magistrates of the city were unhappy with Forth Street and the King – who was shown the copy during Craig’s visit to London – was displeased with St. Giles, as he associated that name with the London district of the same name which had a reputation as a slum, hardly befitting his glorious new capital of North Britain.

A poor quality facsimile of an engraving of 1767 of Craig’s New Town Plan, showing unfamiliar street names. Thank you to Rob Ralston for helping to source this grainy copy in an 1971 paper in an obscure journal.The King’s Scottish physician – Sir John Pringle – sent a letter expressing the displeasure and making some suggestions for improvement to Lord Provost Laurie, and a new copy was made, with George Street central, flanked by Queen Street to the north, and Prince’s Street to the south for George, Prince of Wales. With the cross-streets including Hanover and Frederick (the second son), the King approved and this new trend of naming streets in the city – to the glory of the reigning dynasty – was instituted. Prior to this, nearly all the street names in the city had been functional, describing the builder, owner or principal occupant(s). . An old saying amongst Edinburgh schoolboys – to help them remember – went; “The Queen and the Prince, the Rose and the Thistle, and King George in the Middle”.

You may have noticed in these earlier maps that illustrate Princes Street that some use the form “Prince’s Street” and that others use the more familiar “Princes”. So which is it? The simple answer is both, but never Princes’ Street! The table below gives the varieties used for Princes Street and George Street from the first royally approved plans of 1767 to 1831. The matter was finally settled in 1846 for Princes Street when the GPO street directories finally abandoned the original form of Prince’s Street. That Princes Street was named for two Princes is categorically not the case, it is not a plural, it is a possessive case, it is one where the apostrophe has been lost over time; it was for Prince George and Prince George alone, his brother Prince Frederick got Frederick Street.

MapmakerYearForm of Princes Street UsedForm of George Street UsedJames Craig1767Prince’s GeorgeJohn Andrews1771 Princes GeorgeAndrew Bell1773 Princes GeorgesJohn Ainslie1780Prince’s GeorgeAlexander Kincaid1784Prince’sGeorge’sDaniel Lizars1787Prince’s GeorgeT. Brown & J. Watson1793 PrincesGeorge’sThomas Aitchison1794Prince’s GeorgeJohn Ainslie1804 Princes GeorgesRobert Scott1805 Princes GeorgeGPO1807Prince’s GeorgeRobert Kirkwood1817 Princes GeorgeThomas Brown1818 Princes GeorgesRobert Kirkwood1819 Princes GeorgeRobert Kirkwood1821Prince’s GeorgeRobert Scott1822 Princes GeorgeJohn Wood1823 Princes GeorgeJames Knox1825Prince’s GeorgeJohn Wood1831 Princes GeorgeTable showing the spelling of Princes and George Street used from 1767 to 1831 on maps of the city.Another change in the planned New Town streetnames affected the Northern explansion around 1806; the streets planned with the Latin names of Caledonia Street, Hibernia Street and Anglia Street were Anglicised to Scotland, Dublin and London Streets respectively before any shovels were in the ground. At the same time, a planned Albion Row was merged with the start of Albany Street and took the latter name.

Ainslies’ town plan of 1804 showing planned Caledonia, Hibernia, Anglia Streets and Albion Row. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandAn opposite issue to renaming a street occurred in 1803, when Mrs Maxwell of Carriden (Mary Charlotte Bouverie) complained that her house was on a street with no name! She lived at the extreme west end of the First New Town, where the as-yet unnamed street to the west of Charlotte Square met Princes Street. A disagreement with the Moray Estate over land boundaries meant that the original planned street on the west side of Charlotte Square was never built, and what had been constructed had been given no name. This was resolved by Christening this portion Hope Street, after Charles Hope of Granton, Lord Advocate and the local MP (this is the explanation given by Stuart Harris. An explanation may be that it was for Admiral Sir George Hope of Carriden, a 2nd cousin of Lord Granton). The following year we find a Miss Blair in the Post Office directory for Hope Street.

Kincaid’s Town Plan (left) of 1784, showing the never built western side of Charlotte Square (then still planned as St. George’s Square) and Ainslie’s Town Plan (right) of 1804, showing the compromised updated designs for the west side of Charlotte Square, with the southwest portion now known as Hope Street. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandAn idiosyncrasy of some Edinburgh streets is where the road has one name, but the street addresses along it have another. This is normally the result of a planned or pre-existing street being built along in a piecemeal, protracted manner. A good example of this is London Road, a planned new roadway into the city from the east formed around 1819, but where development along it took around 80 years to complete. Individual street blocks of houses were named by their landowner or builder, after themselves, family connections, royalty, battles, topography, pre-existing local names and more, with opposite sides of the same road frequently having different addresses. In its 1.4 mile Length, there are 19 different street addresses, with London Road itself being the address for relatively few premises.

1944 OS Town Plan of London Road overlaid with the street addresses of the premises along it. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of ScotlandAnother point in case is Leith Walk, a historic walking route between Edinburgh and its port that was only very gradually developed into a carriageway and built along. From the very top (the south or Edinburgh end) of “the Walk” – beginning at current Picardy Place, the facing “pairs” of places on opposite sides of the road went Union Place / Greenside Place; Antigua Street / Baxters Place; Gayfield Place & Haddington Place / Elm Row; Croall Place / Brunswick Place; Albert Place / Shrub Place; George Place / Crichton Place. At this point we reach the Leith and Edinburgh boundary at Pilrig Street.

The Leith end of Leith Walk, Pilrig Street north (down) towards the Foot of the Walk. From Old & New Edinburgh by James Grant.Continuing down into Leith, the historic addresses went Fyfe Place; Kings Place; Orchardfield / Heriot Buildings; Springfield; Ronaldson’s Buildings; Stead’s Place / Anderson Place; Allison’s Place; Whitfield’s Place / Macneill’s Place; Cassell’s Place / Queen’s Place. In 1933, the council street naming committee made a proposal to merge Leith Walk and Leith Street into a continuous numbering sequence and to remove all the older intermediate addresses. Options included calling the whole length simply “Leith Walk”; splitting it into a “Leith Walk South” and “Leith Walk North”; extending Leith Street north to London Road, with everything north of that being Leith Walk. This proposal was never taken forward, and it is only on the Leith half of Leith Walk (i.e. north of Pilrig Street) where the houses are named and numbered as Leith Walk. On the Edinburgh side, the traditional names remains to this day, even though the roadway itself is formally called Leith Walk.

Street renaming generally took place on a case-by-case basis, usually to remove a duplicate name. An exception was a wholesale renaming and de-duplication exercise undertaken in a systematic way between 1965-69 upon the introduction of Post Codes for sending mail. This caused an issue where the traditional use of the old post towns or burghs to disambiguate between streets in the formerly separate burghs of Edinburgh, Leith and Portobello was superseded by simply using “Edinburgh” and the post code. At least 56 streets were renamed in this period, with the general practice being that the Edinburgh name was kept and any duplicates in Leith or Portobello (or both!) were renamed. This resulted in 15 old Leith street names and 8 in Portobello being lost and changed. There were exceptions however, and 5 Edinburgh names were changed where they conflicted with Leith, 4 Leith names were changed where they conflicted with Portobello and 3 Portobello names were changed where they conflicted with Leith.

Amongst others, Edinburgh lost its Pitt Street (to Dundas Street), Duke Street (to Dublin Street), Chapel Lane (to Cathedral Lane), Mitchell Street (to Peffer Place). Leith lost its George Street (to North Fort Street), Queen Street (to Shore Place), Albany Street (to Portland Street), Bank Street (to Seaport Street). Portobello lost its Hope Street (to Rosefield Street), Ramsay Lane (to Beach Lane), Melville Street (to Bellfield Street), Pitt Street (to Pittville Street). The village of Newhaven lost its St. Andrew’s Square (to Fishmarket Square) to avoid confusion with St. Andrew Square in Edinburgh, and it lost its Parliament Square (to Great Michael Square) for the same reason. Across the city as a whole, multiple streets with “Church” or “Hope” in their name were also altered to avoid potential duplicates or ambiguity.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing, perhaps you would like to help contribute towards the running costs of this site – including keeping it ad-free and my book-buying budget to find further stories to bring you – by supporting me on ko-fi. Or please do just share this post on social media or amongst friends.

These threads © 2017-2025, Andy Arthur.

NO AI TRAINING: Any use of the contents of this website to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

#Directories #NewTown #OldTown #postOffice #royalMail #streetNames #Talks #Written2023

One of the 1914 Classical style extensions to Robert Mathieson's 1875 General Post Office building on George Square in Glasgow. The extensions was designed by W.T. Oldrieve and C.J E. Simpson.

#glasgow #architecture #architecturephotography #postoffice #georgesquare

Tiptonville TN Post Office

A small United States Post Office building is situated in a rural area, with an American flag flying prominently in front. Leafless trees and a few scattered clouds create a backdrop for the scene.

Tiptonville, Tennessee

Great River Road

#cityscape #Tennessee #GreatRiverRoad #travelphotography #roadtrip #PostOffice

#streetphotography #streetscene

#photooftheday #fediart

https://fineartamerica.com/featured/tiptonville-tn-post-office-larry-braun.html

Post Office confirms update to 4,000 branches that will change sending money abroad

The #PostOffice in #MapleCreek #Saskatchewan

Another platform in this spinning world of media consolidation/destruction, is Z network. Z has been publishing in one form or another since 1987. Here’s an example of the kind of media analysis it’s known for; the post office is one of my favorite public institutions. Public libraries are another.

#z #postoffice #labor #media #sonalikolhatkar

https://znetwork.org/znetarticle/why-the-right-really-hates-the-postal-service/

Hands Off My Post Office Rally

May 31, 2025

Edmonton Mail Processing Plant (149th Street & 121 Avenue). Photos feature members of CUPW as well as other unions.

--

#yeg #CUPW #labour #union #rally #PostOffice #photojournalism #yegphotographer

Three things to do today, and I've nailed two of them. Was only expecting to pick away at the third item a bit, and now that it's sunny and hot outside that seems accurate.

Got in a nice walk to the #postOffice too! It didn't go well, though. My usual simple mail-a-package transaction, but the clerk who was so smooth at it before seemed to have forgotten all the steps this time. Many retries and we finally got there. Rarely not a challenge. I should keep a scorecard.

#uk #PostOffice #HorizonScandal #ITV #MrBatesVsThePostOffice

BBC News - Post Office offer amounts to just half of my claim, says Bates.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c1kvzkg308wo

Stick with me here:

Maybe the 6 increases in stamp prices wasn't to improve service delivery, but rather to cover derisory gov fines for missed targets - leaving even more money for dividends and exec payouts.

#PostOffice

#NeverPrivatiseEssentialServices

BBC News - Royal Mail could face fine after missing delivery targets

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/czxypp57ewko

Post Offices are gloriously self funding, subtract billionaire profit and bang, good to go. Good jobs, great service, fully Canadian in every nook and cranny, not a dime leaves as profit.

The Post Office is the subject of lies, attacks, conspiracies and bullshit.

It does the exact same service as FedEx but it also SERVES HOMES as if they owned rhe enterprise. Use it, demand it grow and improve.

#Canada #cdnpoli #canpoli #post # #postoffice #CanadaPost #carney

built in 1962, Bangunan Tuanku Syed Putra houses the Penang General Post Office. The building's grid facade and modernist design reflect architectural continuity and peace, symbolising interconnectedness and harmony in Malaysia\u2019s urban landscape

#modernism #ricohgr3 #grid #malaysia #photo #asia #photography #urban #postoffice#1962 #building #architecture #peaceful #penang #office #government

Canada Post should end daily door-to-door delivery, allow part-time work on weekends, report recommends

A report by the commission charged with examining Canada Post's finances has called for the end of door-to-door mail delivery to homes — one of the main reasons for the work stoppage in November.

#mail #delivery #work #postoffice #News #Business

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-post-small-businesses-1.7536827?cmp=rss

Canada Post should end daily door-to-door delivery, allow part-time work on weekends, report recommends

#mail #delivery #work #postoffice #News #Canada

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-post-small-businesses-1.7536827?cmp=rss

Canada Post should end daily door-to-door delivery, allow part-time work on weekends, report recommends

A report by the commission charged with examining Canada Post's finances has called for the end of door-to-door mail delivery to homes — one of the main reasons for the work stoppage in November.

#mail #delivery #work #postoffice #News #Business

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-post-small-businesses-1.7536827?cmp=rss

Canada Post should end daily door-to-door delivery, allow part-time work on weekends, report recommends

A report by the commission charged with examining Canada Post's finances has called for the end of door-to-door mail delivery to homes — one of the main reasons for the work stoppage in November.

#mail #delivery #work #postoffice #News #Business

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-post-small-businesses-1.7536827?cmp=rss