The Simple Dipole: How It Works and How to Get On the Air

1,706 words, 9 minutes read time.

Amateur radio is both a science and an art, and few tools illustrate this duality better than the dipole antenna. For men preparing to enter the world of amateur radio, mastering the dipole provides both practical communication ability and an understanding of RF principles that will serve across the hobby. The dipole is simple, reliable, and educational, offering a starting point that is technically satisfying without requiring complex equipment.

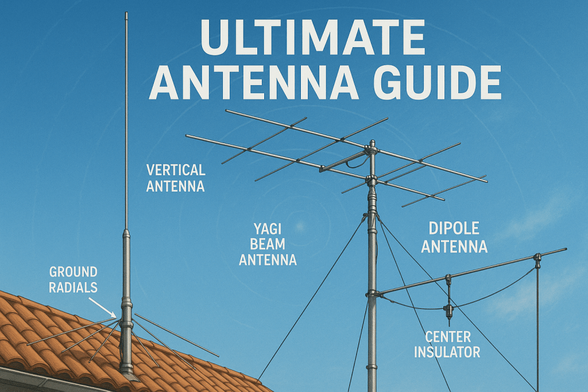

Understanding the Dipole Antenna

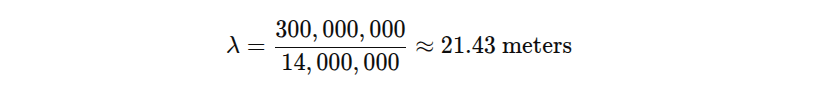

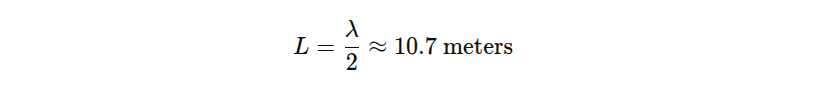

The dipole antenna consists of two conductive elements of equal length, aligned in a straight line with a central feedpoint. This straightforward construction allows it to function effectively across many HF bands. Each half of the antenna resonates at approximately one-quarter wavelength of the target frequency, resulting in a total length near one-half wavelength. The antenna’s resonance is critical; it ensures that electrical energy is efficiently converted into radio waves with minimal reflection back to the transmitter. As described by ARRL resources, the dipole’s simplicity and efficiency have made it a foundational element in amateur radio since the early 20th century.

Height and orientation directly influence the radiation pattern of the dipole. Mounted at roughly half a wavelength above ground, it produces low-angle radiation ideal for long-distance DX contacts. Lower heights create higher-angle lobes suitable for near-vertical incidence skywave (NVIS) communication. Orientation relative to the intended transmission path determines directionality; a dipole aligned north-south favors east-west propagation and vice versa. Inverted-V configurations, where the ends slope downward from the central support, offer nearly equivalent performance while reducing installation complexity.

Feedline considerations are straightforward. Coaxial cable provides a convenient, low-loss path for RF energy from the transceiver to the antenna. A center insulator supports the antenna mechanically and helps maintain symmetry, while optional baluns prevent common-mode currents that may cause noise. For beginners, the simplest center-fed coaxial dipole is sufficient to achieve reliable communication, highlighting the dipole’s accessibility.

Constructing a Dipole

Material selection impacts both durability and performance. Copper and aluminum wires are common choices, providing low resistance and consistent signal radiation. Synthetic insulators like PVC or nylon rope ensure mechanical stability. Secure attachment points, such as tree branches or poles, prevent sagging and maintain the antenna’s intended geometry. While ideal placement is desirable, the dipole is forgiving of small deviations in angle or elevation, making it practical for backyards, parks, or temporary field operations.

The classic length formula, 468 divided by frequency in megahertz, provides a reliable starting point for determining total dipole length in feet. For instance, the 20-meter band (~14 MHz) requires approximately 33 feet total, or 16.5 feet per leg. Small adjustments during installation and tuning may be necessary, and using an SWR meter or antenna analyzer can refine resonance. While more advanced configurations exist, beginners benefit from starting with a straightforward, correctly calculated dipole to build confidence.

Historical context enhances appreciation. Early amateur radio operators used half-wave dipoles because they were inexpensive, easy to construct, and effective for long-range communication. This antenna type set the standard for experimentation, teaching principles of resonance, radiation patterns, and impedance matching that remain relevant today. Understanding the historical significance also reinforces the dipole’s value as an enduring educational tool.

Practical Deployment Tips

Successful dipole operation relies on careful consideration of height, orientation, and local environment. Even minor obstacles, such as nearby metal fences or power lines, can alter the radiation pattern and increase SWR. Trees and poles can serve as convenient supports, but ensuring clearance and stability is essential. For portable operation or temporary setups, lightweight supports and rope insulators provide flexibility while maintaining the antenna’s integrity.

Feedline placement should avoid proximity to conductive surfaces that may introduce interference. Proper grounding and secure connections enhance both safety and signal clarity. Beginners often underestimate the role of small details, yet careful installation ensures that the dipole performs reliably without adding unnecessary complexity.

Experimentation is encouraged. Slight variations in height, angle, or leg length allow operators to observe changes in signal reports and coverage areas. Recording these observations develops an intuitive understanding of antenna behavior and helps operators make informed adjustments. Practical experience reinforces the theoretical knowledge gained from study, bridging the gap between calculation and real-world performance.

Safety Considerations

Safety is paramount when installing antennas. Dipoles should never be placed near power lines, and care must be taken when working at heights. Securing the antenna to prevent movement or detachment minimizes risk, while proper grounding protects equipment and operators from electrical hazards. Experienced operators emphasize that following standard safety practices ensures a successful and secure installation.

Mechanical considerations, such as tensioning wires to prevent sag and using robust insulators, enhance both longevity and safety. Environmental factors like wind, snow, or ice can stress antenna components, so reinforcing attachment points and selecting durable materials are important. By prioritizing safety, new operators can focus on learning and experimentation with confidence.

Scaling and Variations

Once comfortable with a basic dipole, operators can explore enhancements. Trap dipoles allow operation on multiple bands without complex switching. Off-center-fed dipoles provide broader bandwidth and different radiation patterns. Inverted-V arrangements optimize performance in limited spaces. Each variation builds on the foundational principles of the simple half-wave dipole, enabling continued learning and experimentation.

Multi-element arrays, directional antennas, and portable configurations all trace their conceptual roots to the dipole. Mastering the basic design facilitates understanding of these more advanced setups, illustrating how a simple, well-understood antenna can serve as a stepping stone to complex systems. These experiences deepen knowledge and encourage practical experimentation, reinforcing the learning process.

SEO Section: HF Antenna Fundamentals

A dipole is a fundamental HF antenna that introduces new operators to the physics of radio waves. Understanding half-wave resonance, feedpoint impedance, and radiation patterns provides insight into how antennas convert electrical energy into RF signals. This foundational knowledge is essential for troubleshooting, optimizing SWR, and improving communication efficiency. By emphasizing principles over complexity, beginners gain confidence in both construction and operation.

Radiation patterns, including main lobes and nulls, help operators predict performance in different directions. For instance, horizontal dipoles favor low-angle propagation ideal for DX contacts, while lower heights enhance NVIS communication. Hands-on observation of these effects reinforces theory, creating a practical understanding that supports further experimentation. Combining calculation, measurement, and observation ensures comprehensive learning.

Feedline interaction with the antenna is another critical area. Understanding the role of coaxial cables, baluns, and common-mode currents prevents signal degradation and noise introduction. Proper installation of these components complements the dipole’s performance, ensuring that energy reaches the air efficiently. SEO-friendly discussions of feedline types, impedance, and SWR optimization make the content accessible and relevant to search engines while educating readers.

SEO Section: Practical Deployment and Experimentation

Practical deployment tips enhance the learning experience. Emphasizing placement, height, and orientation prepares operators for real-world installation. Diagrams and illustrations of dipole configurations assist comprehension, while descriptive explanations connect theory to practice. Hands-on experimentation, including SWR measurement and signal reporting, allows readers to observe the immediate effects of changes in antenna setup.

Portable operation offers additional opportunities for learning. Lightweight supports, rope insulators, and flexible feedline arrangements demonstrate adaptability. Documenting results reinforces the link between adjustments and performance, creating a feedback loop that enhances understanding. These practices engage readers in active learning, encouraging both experimentation and consistent improvement.

Community involvement further strengthens practical application. Participation in club demonstrations, online forums, and local events provides guidance, mentorship, and insight into regional propagation characteristics. Sharing experiences with other operators allows new hams to validate their observations and learn alternative approaches, fostering a collaborative environment conducive to growth.

SEO Section: Safety, Materials, and Longevity

Safety considerations are essential in antenna deployment. Placement clearances, secure supports, grounding, and avoidance of power lines ensure operator protection. Selecting durable materials, such as copper or aluminum conductors and synthetic insulators, contributes to long-term reliability. Reinforced attachment points prevent mechanical failures due to wind, ice, or environmental stress.

Proper tensioning of wires and careful alignment maintain intended radiation patterns. Minor adjustments can influence SWR and overall performance, highlighting the importance of meticulous installation. Safety, combined with thoughtful material selection, ensures that beginners experience both immediate functionality and long-term stability in their dipole setups.

Routine inspections and adjustments enhance longevity. Observing wear on insulators, checking for corrosion, and verifying secure attachments prevent unexpected failures. This approach encourages disciplined maintenance practices and reinforces the importance of responsibility in antenna management, ensuring that operators can safely and reliably use their dipoles for years.

SEO Section: Scaling, Variations, and Future Exploration

After mastering the basic dipole, new operators can explore trap dipoles for multi-band use, off-center-fed designs for wider bandwidth, and inverted-V configurations for constrained spaces. Each variation demonstrates the adaptability of the dipole and provides opportunities for continued learning. Understanding these modifications deepens comprehension of RF principles and enhances practical skills.

Advanced applications, such as multi-element arrays or portable field setups, rely on the foundational knowledge gained from dipole experimentation. Observing how basic concepts scale to complex systems reinforces learning and encourages innovation. By exploring these variations, operators develop both technical expertise and confidence in problem-solving.

Future exploration includes integrating the dipole with emerging digital modes, monitoring propagation patterns, and experimenting with automated tuning systems. The dipole’s enduring relevance ensures that new operators can continually expand their capabilities while remaining grounded in essential principles. SEO-focused content highlighting these applications provides valuable guidance for readers seeking both practical and theoretical growth.

Call to Action

If this story caught your attention, don’t just scroll past. Join the community—men sharing skills, stories, and experiences. Subscribe for more posts like this, drop a comment about your projects or lessons learned, or reach out and tell me what you’re building or experimenting with. Let’s grow together.

D. Bryan King

Sources

- ARRL Antenna Resources

- eHam.net Technical Articles

- QRZ.com Antenna Guides

- RigPix Antenna Technical Data

- Ham Universe Antenna Tutorials

- DX Engineering Technical Guides

- K0BG Antenna Insights

- VE3VN Antenna Reference

- Electronics Tutorials: HF Dipoles

- AMSAT Antenna Information

- RF Engineering Antenna Designs

- Ham Radio Pages Antenna Section

- IK3OQV Dipole Experiments

- W1AEX Antenna Notes

- ARRL Antenna Handbook PDF

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author. The information provided is based on personal research, experience, and understanding of the subject matter at the time of writing. Readers should consult relevant experts or authorities for specific guidance related to their unique situations.

#20mDipole #40mDipole #aluminumAntenna #amateurRadioAntenna #amateurRadioEducation #amateurRadioHobby #antennaBasics #antennaBeginnerGuide #antennaBuilding #antennaCalculations #antennaConstruction #antennaDemonstration #antennaDeployment #antennaDesign #antennaDiagram #antennaDIY #antennaEfficiency #antennaExperiment #antennaExperimentIdeas #antennaExperimentation #antennaFundamentals #antennaGuide #antennaHeight #antennaImprovement #antennaInsights #antennaInstallation #antennaKnowledge #antennaLearning #antennaMaintenance #antennaMaterials #antennaNotes #antennaObservation #antennaOrientation #antennaPatterns #antennaPerformance #antennaPhysics #antennaPlacement #antennaPrinciples #antennaProject #antennaReference #antennaResonance #antennaResources #antennaSafety #antennaTesting #antennaTheory #antennaTips #antennaTroubleshooting #antennaTuning #antennaTutorial #ARRLAntenna #beginnerHam #coaxFeedline #copperWireAntenna #dipoleAntenna #dipoleSetup #dipoleTutorial #DXContacts #electromagneticWaves #feedpointImpedance #fieldAntennaSetup #gettingOnTheAir #halfWaveDipole #hamRadioAntennas #hamRadioGuide #hamRadioLearning #hamRadioSetup #hamRadioTips #hfAntenna #HFBands #HFCommunication #HFPropagation #invertedVDipole #lowPowerAntenna #multiBandDipole #NVISPropagation #offCenterFedDipole #portableDipole #practicalAntenna #PVCInsulators #QRPAntenna #radiationPattern #radioAntennaGuide #radioPropagation #radioScience #radioWaves #RFPrinciples #RFRadiation #ropeInsulators #simpleDipole #SWROptimization #trapDipole #VHFAntennas #wireAntennas