Understanding Antennas: A Beginner’s Guide

1,790 words, 9 minutes read time.

If you’ve ever tuned a receiver or held a handheld transceiver, you know the thrill of connecting with someone miles away over invisible waves. Yet, no matter how impressive your radio or its features, the antenna remains the real workhorse of your station. Think of it as the engine of a sports car: you can have the finest chassis and interior, but without a capable engine, performance suffers. The same principle applies to ham radio. A well-designed antenna can make even modest equipment sing, while a high-powered rig can struggle when paired with a poorly chosen or installed antenna.

This guide isn’t about licensing or exam questions. Instead, it’s about helping you master the science and art of antennas so that when the time comes to pursue your license, you already understand what makes an antenna work—and why it matters more than most novices realize. By the end, you’ll have the insight to make informed decisions about design, installation, tuning, and optimization, and you’ll understand why the antenna is the heart of every station.

The Big Picture: What an Antenna Really Does

An antenna is, at its simplest, a bridge between your radio and the world. It converts electrical energy from your transmitter into electromagnetic waves that propagate through the air. On receive, it captures those waves and converts them back into electrical signals for your radio to decode. While radios can be complex, antennas are governed by elegant, consistent physical principles.

Key characteristics define performance: frequency, wavelength, radiation pattern, feed-point location, and impedance. Frequency determines physical size; lower frequencies need longer elements, while higher frequencies allow smaller antennas. Wavelength defines the resonant length of the antenna, determining how efficiently it radiates or receives energy. Impedance is crucial for matching the antenna to your radio and minimizing power loss. A mismatch can result in reflected energy, poor performance, or even equipment stress.

The antenna’s shape, orientation, and height relative to the ground all shape its radiation pattern—the “footprint” over which your signal travels. A simple horizontal dipole a few feet off the ground will behave very differently from the same dipole mounted 30 feet high. Understanding these nuances early will save frustration later, especially when space, trees, and rooftops impose real-world constraints.

Antenna Theory for Beginners

When learning about antennas, it helps to think in terms of waves. Radio waves have both a wavelength and frequency. A quarter-wave or half-wave element resonates when its physical length is proportional to the wavelength of your frequency of interest. This resonance ensures maximum energy transfer and minimal loss.

Impedance is another cornerstone concept. Most amateur radios expect a 50-ohm load. An antenna presenting a significantly different impedance causes reflections back to the transmitter, measurable as Standing Wave Ratio (SWR). Understanding SWR is crucial: a high SWR indicates energy is bouncing back toward your radio, while a low SWR shows efficient transfer. Modern antenna analyzers make this process easier, but grasping the principle early ensures you interpret readings correctly.

Height, feedline quality, and nearby obstacles all interact with theory. A well-placed antenna can outperform a technically superior antenna that’s poorly installed. Even the choice of coax or ladder line matters; losses in feedlines reduce overall effectiveness. Understanding these elements before you even cut your first wire sets a foundation that will carry you through your first contacts and beyond.

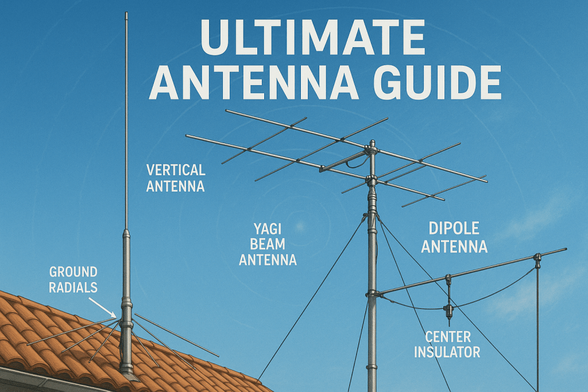

Exploring Common Antenna Types

Choosing the right antenna often comes down to balancing your goals, available space, and budget. The horizontal dipole is a classic starting point: easy to construct, effective, and versatile. Variations like the inverted-V conserve space while maintaining reasonable efficiency. The G5RV multiband wire is another beginner favorite, providing access to multiple bands with a single installation.

Vertical antennas, including ground-plane designs, offer a smaller footprint and omnidirectional coverage, making them suitable for limited space. However, verticals often require a decent ground system for efficiency. Portable hams often start with rubber-duck handheld antennas or lightweight whips. While these are limited in range and performance, they provide essential practice in tuning, orientation, and handling.

Directional antennas, such as beams or Yagis, allow you to focus power in a particular direction, improving signal strength and reception. While these require more planning, supports, and often rotators, they demonstrate the profound impact antenna geometry has on performance. Even simple directional configurations like a corner reflector or quad can dramatically improve reception without increasing transmitter power.

Installation Considerations

An antenna’s effectiveness hinges on proper installation. Begin with a site survey. Note available supports, nearby obstacles, and ground conditions. Trees, metal structures, and other antennas can influence radiation patterns and SWR. Height is your ally: higher antennas generally produce lower take-off angles, enhancing long-distance performance.

Feedline choice is critical. Coaxial cable is convenient, widely available, and easy to handle, but every foot adds loss, especially at higher frequencies. Ladder line or open-wire feedlines minimize loss but require careful routing and insulation. Matching devices like baluns and tuners correct impedance mismatches and maximize power transfer, but they cannot compensate for poor placement or inadequate height.

Grounding isn’t just about lightning protection—it also improves safety and can reduce RF interference in your station. A properly grounded antenna system protects both your equipment and your home while ensuring more consistent performance.

Tuning and Optimizing

Once your antenna is up, tuning is the next step. Measure SWR across your desired frequency range. Small adjustments—trimming or lengthening elements, adjusting angle or height—can significantly improve resonance. Even a minor shift in a tree branch or support can alter SWR readings.

Baluns and matching networks help achieve impedance compatibility, but efficiency always begins with the antenna itself. Understand feedline losses versus antenna gain. In many cases, a slightly less “ideal” antenna installed correctly outperforms a theoretically perfect antenna with installation issues.

Routine monitoring ensures sustained performance. Seasonal changes, weather, or vegetation growth can subtly affect your antenna. Keeping a notebook with element lengths, feedline types, and SWR readings creates a reference that saves countless hours troubleshooting later.

Understanding the Math Behind Antennas

Even if licensing isn’t your immediate goal, some math from the Technician and General exams is invaluable for designing and tuning antennas. Let’s break it down.

Wavelength and Antenna Lengths

Radio waves travel at the speed of light, roughly 300,000,000 meters per second. The wavelength (λ\lambdaλ) is calculated as:

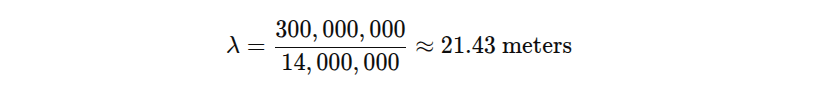

Where ccc is the speed of light in meters per second and fff is frequency in hertz. For example, a 14 MHz signal:

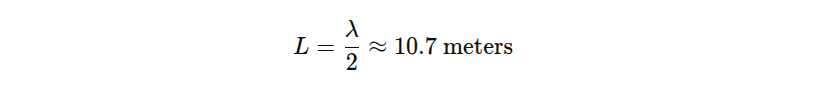

Using wavelength, antenna lengths are derived. A half-wave dipole, the most common, is approximately:

A quarter-wave vertical would be:

These formulas allow you to calculate almost any basic wire antenna length accurately.

Impedance and SWR

Understanding SWR requires a bit of algebra, but the principle is simple. SWR is the ratio of the maximum to minimum voltage on the line:

An SWR of 1:1 indicates perfect impedance matching. If your antenna presents 75 ohms to a 50-ohm transmitter, SWR rises to 1.5:1. Knowing this math helps interpret readings and adjust antenna lengths to minimize reflected power.

Power Loss in Feedlines

Feedline loss depends on frequency, cable type, and length. The basic relationship is:

Where III is current and RRR is the resistance of the line. While hams rarely calculate exact wattage losses, understanding that longer coax and higher frequency result in more loss helps you make smart installation choices. For example, 50 feet of RG-58 at 14 MHz may lose several tenths of a dB, while the same length at 144 MHz loses significantly more.

Resonance Adjustment

Small adjustments in element length directly influence resonance. For a half-wave dipole, a change of 1% in length shifts resonance by roughly 1% of the operating frequency. Understanding the proportionate effect of element trimming helps you fine-tune SWR without guesswork.

Growth Path: Beyond the Beginner Antenna

Your first antenna is not the end of your journey—it’s the foundation. Once you understand resonance, SWR, feedlines, and radiation patterns, upgrading to more complex systems becomes far less intimidating. Transitioning from a simple dipole to a directional beam, or from a single-band wire to a multiband installation, is much smoother when grounded in fundamental knowledge.

Experimentation is encouraged. Try different heights, orientations, or portable setups. Document every change. Over time, this builds not just skill but confidence. A well-documented antenna journey also creates a valuable reference for troubleshooting or mentoring newcomers in your local club.

Practical Tips and Takeaways

Start simple and test early. A straightforward dipole or vertical, installed thoughtfully, offers a playground for learning without the frustration of complex setups. Prioritize site and installation over chasing high-gain claims; a well-placed, modest antenna frequently outperforms flashy designs.

Keep detailed records. Note heights, element lengths, SWR readings, and observations. Engage with local clubs or online communities to exchange insights. Remember, there’s no “perfect” antenna; each design involves trade-offs. Your goal is functional, efficient, and maintainable—something that gets you on the air while teaching you valuable lessons along the way.

Conclusion

Understanding antennas is the cornerstone of being a competent ham operator. By mastering fundamental theory, experimenting with design and installation, learning to optimize performance, and applying some of the math behind resonant lengths and SWR, you lay a solid foundation for the future. The knowledge you gain now makes licensing less about memorization and more about applying what you already know.

The antenna is more than a piece of hardware; it’s a bridge between your curiosity and the world. Build it thoughtfully, learn from each adjustment, and your first transmissions will carry far further than just radio waves—they’ll carry experience, understanding, and confidence.

Your journey is just beginning, and the airwaves are waiting.

Call to Action

If this blog caught your attention, don’t just scroll past. Join the community—men sharing skills, stories, and experiences. Subscribe for more posts like this, drop a comment about your projects or lessons learned, or reach out and tell me what you’re building or experimenting with. Let’s grow together.

D. Bryan King

Sources

- “Your First Antenna” — ARRL

- “The Different Types of Ham Radio Antennas” — Ham Radio Prep

- “Beginners’ Corner” — Practical Antennas

- “Ham Radio Antennas: Types, Differences, and Pros & Cons” — Stryker Radios Blog

- “How Antennas Work” — ARRL

- “Building Simple Antennas” — ARRL

- “A Beginner’s Guide to SWR” — Practical Antennas

- “Impedance” — Practical Antennas

- “Feeding the Antenna” — Practical Antennas

- “Antenna Modeling for Beginners” — ARRL

- “Top 5 HF Ham Radio Antennas for Beginners” — World Radio League

- “Hexbeam” — Wikipedia (directional antenna type overview)

- “Quad Antenna” — Wikipedia (another antenna type overview)

- “Ch 4 – Propagation, Antennas & Feedlines” — ARRL

- “Corner Reflector Antenna” — Wikipedia (directional antenna concept)

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author. The information provided is based on personal research, experience, and understanding of the subject matter at the time of writing. Readers should consult relevant experts or authorities for specific guidance related to their unique situations.

Related Posts

Rate this:

#advancedAntennas #amateurRadioLearning #amateurRadioTips #antennaAnalyzer #antennaBlog #antennaCalculators #antennaConstruction #antennaCoverage #antennaDesign #antennaEfficiency #antennaEfficiencyTips #antennaExperiments #antennaFeedline #antennaForBeginners #antennaFormulas #antennaGain #antennaGrounding #antennaGuide #antennaHeight #antennaImpedance #antennaInstallation #antennaMatching #antennaMaterials #antennaMath #antennaModeling #antennaOrientation #antennaPerformance #antennaPolarization #antennaReferenceGuide #antennaSoftware #antennaTesting #antennaTheory #antennaTipsAndTricks #antennaTroubleshooting #antennaTuning #baseStationAntennas #beamAntenna #coaxialCable #dipoleAntenna #directionalAntennas #diyAntennas #fccExam #generalLicense #groundPlaneAntenna #hamRadioAntennas #hamRadioClubs #hamRadioCommunity #hamRadioMath #hamRadioProjects #hamRadioResources #hamRadioSetup #hamRadioSignals #hfAntennas #hfBandAntennas #hfPropagation #ionosphereEffects #mobileAntennas #omnidirectionalAntennas #portableAntennas #practicalAntennaGuide #propagationTips #radiationPattern #radioCommunication #radioEquipment #radioFrequency #radioHobby #radioLicensing #radioPerformance #radioPropagation #radioScience #radioSignalStrength #radioWavePropagation #resonantFrequency #rfDesign #solarActivity #swrCalculation #technicianLicense #uhfAntennas #uhfBandAntennas #uhfPropagation #verticalAntenna #vhfAntennas #vhfBandAntennas #vhfPropagation #yagiAntenna