Knowing-in-action: Bridging the theory-practice divide in global health

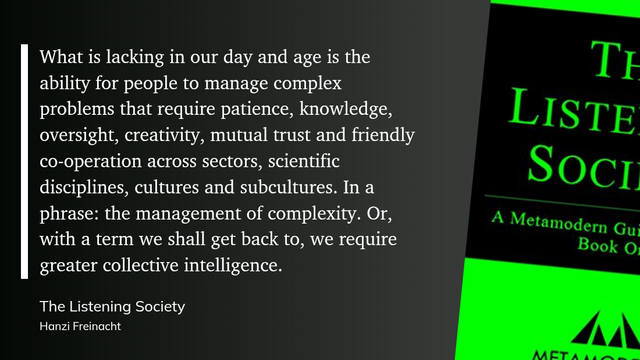

The gap between theoretical knowledge and practical implementation remains one of the most persistent challenges in global health. This divide manifests in multiple ways: research that fails to address practitioners’ urgent needs, innovations from the field that never inform formal evidence systems, and capacity building approaches that cannot meet the massive scale of learning required. Donald Schön’s seminal 1995 analysis of the “dilemma of rigor or relevance” in professional practice offers crucial insights for “knowing-in-action“. It can help us understand why transforming global health requires new ways of knowing – a new epistemology.

Listen to this article below. Subscribe to The Geneva Learning Foundation’s podcast for more audio content.

https://youtu.be/MvrW5ct8uuw

Schön’s analysis: The dilemma of rigor or relevance

Schön begins by examining how knowledge becomes institutionalized through education. Using elementary school mathematics as an example, he describes how knowledge is broken into discrete units (“math facts”), organized into progressive modules, assembled into curricula, and measured through standardized tests. This systematization shapes not just content but the entire organization of time, space, and institutional arrangements.

From this foundation, Schön introduces his central metaphor of two contrasting landscapes in professional practice that prevent “knowing-in-action”. As he describes it:

“In the varied topography of professional practice, there is a high, hard ground overlooking a swamp. On the high ground, manageable problems lend themselves to solution through the use of research-based theory and technique. In the swampy lowlands, problems are messy and confusing and incapable of technical solution.”

The cruel irony, Schön observes, lies in the relative importance of these terrains: “The problems of the high ground tend to be relatively unimportant to individuals or to society at large, however great their technical interest may be, while in the swamp lie the problems of greatest human concern.”

This creates what Schön calls the “dilemma of rigor or relevance” – practitioners must choose between remaining on the high ground where they can maintain technical rigor or descending into the swamp where they must rely on experience, intuition, and what he terms “muddling through.”

The historical roots of the divide

Schön traces this dilemma to the epistemology embedded in modern research universities. Drawing on Edward Shils’s historical analysis, he describes how American scholars returning from Germany after the Civil War brought back “the German idea of the university as a place in which to do research that contributes to fundamental knowledge, preferably through science.”

This was, as Schön notes, “a very strange idea in 1870,” running counter to the prevailing British model of universities as sanctuaries for liberal arts or finishing schools for gentlemen. The new model first took root at Johns Hopkins University, whose president embraced the “bizarre notion that professors should be recruited, promoted, and granted tenure on the basis of their contributions to fundamental knowledge.”

This shift created what Schön terms the “Veblenian bargain” (named after Thorstein Veblen), establishing a separation between:

- Research universities focused on “true scholarship” and fundamental knowledge

- Professional schools dedicated to practical training

Knowing-in-action in global health: From fragmentation to integration

The historical division between theory and practice that Schön identified continues to shape global health in profound and often problematic ways. This manifests in three interconnected challenges that demand our urgent attention: the knowledge-practice gap, the scale challenge, and the complexity challenge. Yet emerging approaches suggest potential paths forward, particularly through structured peer learning networks that could help bridge Schön’s “high ground” and “swamp.”

Three fundamental challenges

Challenge #1: The knowing-in-action divide

The separation between research institutions and field practice creates not just an academic concern but a practical crisis in healthcare delivery. Consider the response to COVID-19: while research institutions rapidly generated new knowledge about the virus, frontline health workers struggled to translate this into practical approaches for their specific contexts. Their hard-won insights about what worked in different settings rarely made it back into formal evidence systems, epitomizing the one-way flow of knowledge that impoverishes both research and practice.

This pattern repeats across global health. Research agendas, shaped by academic incentives and funding priorities, often fail to address practitioners’ most pressing challenges. A community health worker in rural Bangladesh facing complex challenges around vaccine hesitancy may struggle to find relevant guidance – while global experts are convinced that they already have all the answers. Meanwhile, local solutions to building vaccine confidence remain uncaptured by formal knowledge systems.

The rise of implementation science attempts to bridge this divide, yet often remains subordinate to “pure” research in academic hierarchies. This reflects Schön’s observation about the privileging of high ground problems over swampy ones, even when the latter hold greater practical significance.

Challenge #2: The scale imperative

Traditional approaches to professional education face fundamental limitations in meeting the massive need for health worker capacity building. The World Health Organization projects a shortfall of 10 million health workers by 2030, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. Conventional training approaches that rely on cascading knowledge through workshops and formal courses can reach only a fraction of those who need support.

More fundamentally, these knowledge transmission models prove inadequate for addressing complex local realities. A standardized curriculum developed by experts, no matter how well-designed, cannot anticipate the diverse challenges health workers face across different contexts. When a district immunization manager in Nigeria must adapt vaccination strategies for nomadic populations during a drought, they need more than pre-packaged knowledge – they need ways to learn from others who are facing similar challenges.

Resource constraints further limit the reach of conventional approaches. The cost of traditional training programmes, both in money and time away from service delivery, makes it impossible to scale them to meet the need. Yet the human cost of this capacity gap, measured in preventable illness and death, demands urgent solutions.

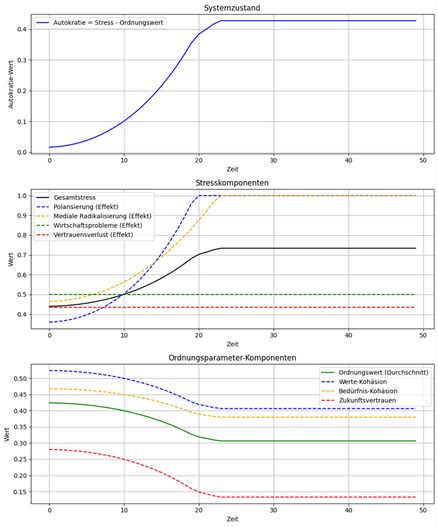

Challenge #3: The complexity conundrum

Contemporary global health faces challenges that fundamentally resist standardized technical solutions. Climate change exemplifies this complexity, creating cascading effects on health systems and communities that cannot be addressed through linear interventions. When rising temperatures alter disease patterns while simultaneously disrupting cold chains for vaccine delivery, no single technical fix suffices.

Similarly, emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases demand responses that cross traditional boundaries between animal and human health, environmental factors, and social determinants. Health workforce development must grapple with complex systemic issues around motivation, retention, and capacity building. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how traditional approaches to health system strengthening often prove inadequate in the face of complex adaptive challenges.

Emerging solutions: A new paradigm for learning and practice

Recent innovations suggest promising approaches to bridging these divides through structured peer learning networks. Digital platforms enable health workers to share experiences and solutions across geographical boundaries, creating new possibilities for scaled learning that maintains local relevance.

Solution #1: The power of structured peer learning

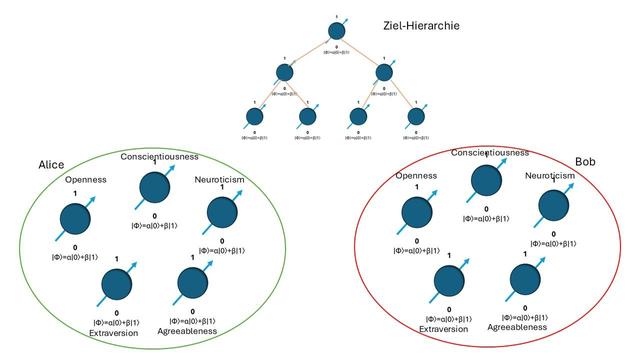

Experience from digital learning networks demonstrates how structured peer interaction can enable more efficient and effective knowledge sharing than traditional top-down approaches. When health workers can directly connect with peers facing similar challenges, they not only share solutions but collectively generate new knowledge through their interactions.

These networks provide mechanisms for validating practical knowledge through peer review processes that complement traditional academic validation. A successful intervention developed by a rural clinic in Thailand can be critically examined by peers, adapted for different contexts, and rapidly disseminated across the network. This creates a more dynamic and responsive knowledge ecosystem than traditional publication cycles allow.

Solution #2: Network effects and collective intelligence

The potential of practitioner networks extends beyond simple knowledge sharing. When properly structured, these networks create possibilities for:

- Rapid adaptation to emerging challenges through real-time sharing of experiences

- Collective problem-solving that draws on diverse perspectives and contexts

- Systematic capture and analysis of field innovations

- Development of context-specific solutions that build on shared learning

Most importantly, these networks can help bridge Schön’s high ground and swamp by creating dialogue between different forms of knowledge and practice. They provide spaces where academic research can inform field practice while simultaneously allowing field insights to shape research agendas.

Four principles toward knowing-in-action for global health

Drawing on Schön’s call for a “new epistemology,” we can identify four principles for transforming how we know what we know in global health:

Principle #1: Valuing multiple forms of knowledge

The complexity of contemporary health challenges demands recognition of multiple valid forms of knowledge. The practical wisdom developed by a community health worker through years of service deserves attention alongside randomized controlled trials. This requires challenging existing hierarchies of evidence while maintaining rigorous standards for validating knowledge claims.

Principle #2: Enabling knowledge creation from practice

Health workers must be supported as knowledge producers, not just knowledge consumers. This means creating structures for systematically capturing and validating field insights, building evidence from implementation experience, and enabling continuous learning from practice. Digital platforms can provide scaffolding for this knowledge creation while ensuring quality through peer review processes.

Principle #3: Scaling through networked learning

Traditional scaling approaches that rely on standardization and top-down dissemination must be complemented by networked learning to create and amplify knowing-in-action. This means building systems that can:

- Connect practitioners across contexts and boundaries

- Enable peer validation of knowledge

- Support rapid dissemination of innovations

- Build collective intelligence through structured interaction

Principle #4: Embracing complexity

Rather than seeking to reduce complexity through standardization, health systems must build capacity for working effectively within complex adaptive systems. This means supporting adaptive learning, enabling context-specific solutions, and building capacity for systems thinking at all levels.

The challenges facing global health today demand new ways of creating, validating, and sharing knowledge. By embracing approaches that bridge Schön’s high ground and swamp, we may find paths toward health systems that are both more rigorous and more relevant to the communities they serve.

Looking forward

Schön’s analysis helps explain why traditional approaches to global health knowledge and learning often fall short. More importantly, it points toward solutions that could help bridge the theory-practice divide to support knowing-in-action:

- New digital platforms that enable peer learning at scale

- Networks that connect practitioners across contexts

- Approaches that validate practical knowledge

- Systems that support rapid learning and adaptation

Schön’s insights remain remarkably relevant to contemporary global health challenges. His call for a new epistemology that can bridge theory and practice speaks directly to our current needs. By embracing new approaches to learning and knowledge creation that honor both rigor and relevance, we may find ways to address the complex challenges that lie ahead.

The key lies not in choosing between high ground and swamp, but in building new kinds of bridges between them – bridges that can support the massive scale of learning needed while maintaining the local relevance essential for impact. Recent innovations in peer learning networks and digital platforms suggest this bridging may be increasingly possible, offering hope for more effective global health practice in an increasingly complex world.

The challenge now is to develop and implement these bridging approaches at the scale needed to support global health workers worldwide. This will require new ways of thinking about knowledge, learning, and practice – ways that honor both the rigor of research and the wisdom of experience. The future of global health may depend on our success in this endeavor.

Listen to the AI podcast deep dive about this article

https://youtu.be/Mm8iRc227Y8

Reference

Schön, Donald A., 1995. Knowing-in-action: The new scholarship requires a new epistemology. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 27, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1995.10544673

Image: The Geneva Learning Foundation Collection © 2024

Share this:

#1 #2 #3 #4 #CollectiveIntelligence #DonaldASchön #epistemology #globalHealth #knowDoGap #networkedLearning #peerLearning #scale