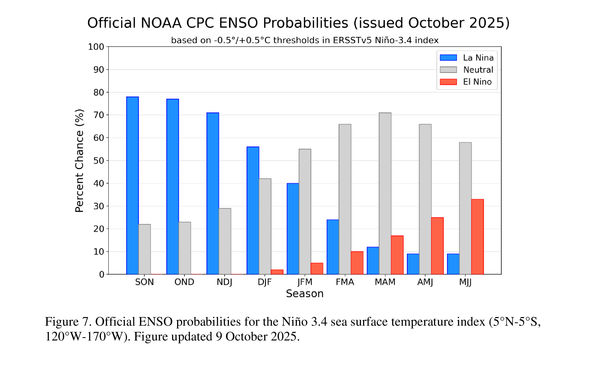

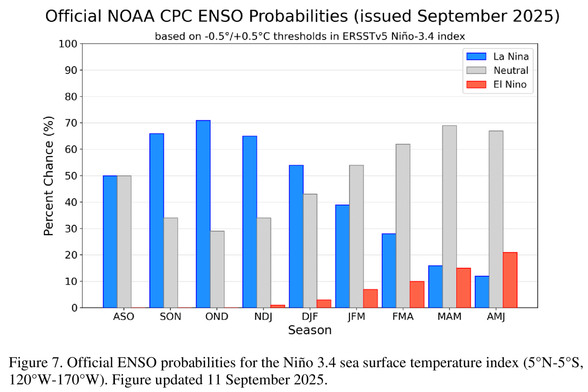

La Niña has arrived and is forecast to persist for the remainder of 2025

Sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific have dropped below average, signaling the return of La Niña conditions. This follows an ENSO-neutral summer and a weak La Niña last winter. In response, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center has issued a La Niña advisory, noting that ocean-atmosphere coupling consistent with La Niña is now evident.

The first signs of this La Niña began showing up several months ago, and I’ve been tracking those signals since early summer. Forecasts indicate that this event will be both weak and short-lived, with a return to ENSO-neutral conditions likely by early 2026.

Ingalls Weather thanks the support it gets from donors. Please consider making a small donation at this link to help me pay for the website and access to premium weather data.

Because this La Niña is expected to remain weak, its influence on the upcoming North American winter will probably be limited. The overall signal hints at a slight tendency toward above-average precipitation in parts of the Pacific Northwest and a small cool bias, but local weather patterns will depend more on other regional factors.

One of the most important of those is the area of warm water off the West Coast often referred to as the Blob. The Blob strengthens high pressure near the coast, which can divert the storm track northward toward Alaska and the northern coast of British Columbia.

Subscribe

That pattern was quite noticeable through September, when most storm systems stayed well to the north of the major Northwest cities. It’s beginning to ease now, with more fronts reaching farther south into the Pacific Northwest as the wet season progresses. This seasonal shift is typical as the jet stream gradually slides southward through autumn and winter.

Another factor worth watching is the Siberian snowpack. Snowfall across Siberia has begun the season above average, and if that continues south of roughly 60°N latitude, it could enhance storm development along the Japanese and Kamchatka coasts, which sometimes translates into stronger downstream systems crossing the Pacific.

In general, a weak La Niña can behave much like an ENSO-neutral year. These neutral years often produce active, stormy autumns in the Pacific Northwest, with frequent regional low-pressure systems bringing wind and rain. When that combines with the influence of the Blob, however, snowfall can lag. The first half of the winter may see a slower snowpack build-up, much like the slow start we saw in fall 2024.

Several climate signals are competing for influence this year. La Niña is present but weak, offering only a mild cool-wet signal. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation may add a little reinforcement to that cool tendency if it stays in a negative phase.

Meanwhile, the Blob tilts conditions warmer and drier near the coast. Given its proximity, I suspect the Blob will play the stronger role in shaping early-season weather. Siberian snow cover remains the wild card.

If the above-average snowpack trend there persists, it could help set up a more active storm pattern later in the winter, particularly after mid-January. But overall, the mix of opposing influences makes it difficult to pin down a clear picture of how the season will unfold.

For now, a reasonable expectation is a muted, uneven start to winter followed by a possible uptick in activity during the second half of the season — though, as always, much will depend on how these evolving patterns interact over the next few months.

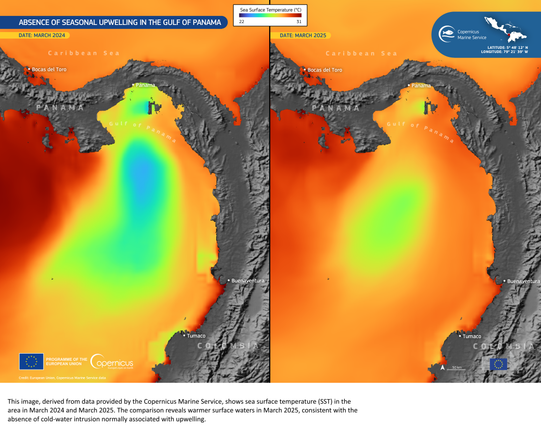

The featured image is sea surface temperature compared to average in the Tropical Pacific. The below average region along the equator signals La Niña’s arrival. (NOAA)

#BCstorm #lanina #orwx #wawx #Weather #Winter